The men staff and students of the Goldsmiths’ Training Department 1907. William Thomas Young is the lecturer sitting centre of the front row, 7th from left and right.

One day in the middle of July 1917 a telegram boy delivered the message to Mrs Hilda Young that her husband, Lieutenant William Thomas Young, had been killed in action.

It is impossible to imagine the shock and grief of such news; particularly when she was caring for their infant daughter, Diana, born just over a year before.

He had been blown up by shell fire on the 12th of July while serving with number 12 Heavy Battery, the Royal Garrison Artillery during the battle of Passchendaele.

It was also the first day the German Army had deployed mustard gas.

He was 36-years-old and had been hailed as one of the country’s most promising scholars of English Literature.

He had been lecturer in English at the University of London, Goldsmiths’ College since September 1906 and he was also Joint Editor of the prestigious Cambridge Anthologies.

Goldsmiths’ women students and staff 1905-7. Three of the men, including the Warden, William Loring and Vice Principal Thomas Raymont still managed to ‘inveigle’ themselves into the frame. You can see them standing at the back to the far left and right.

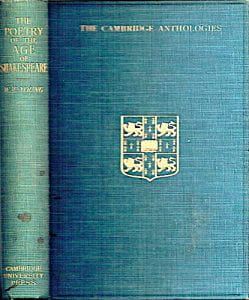

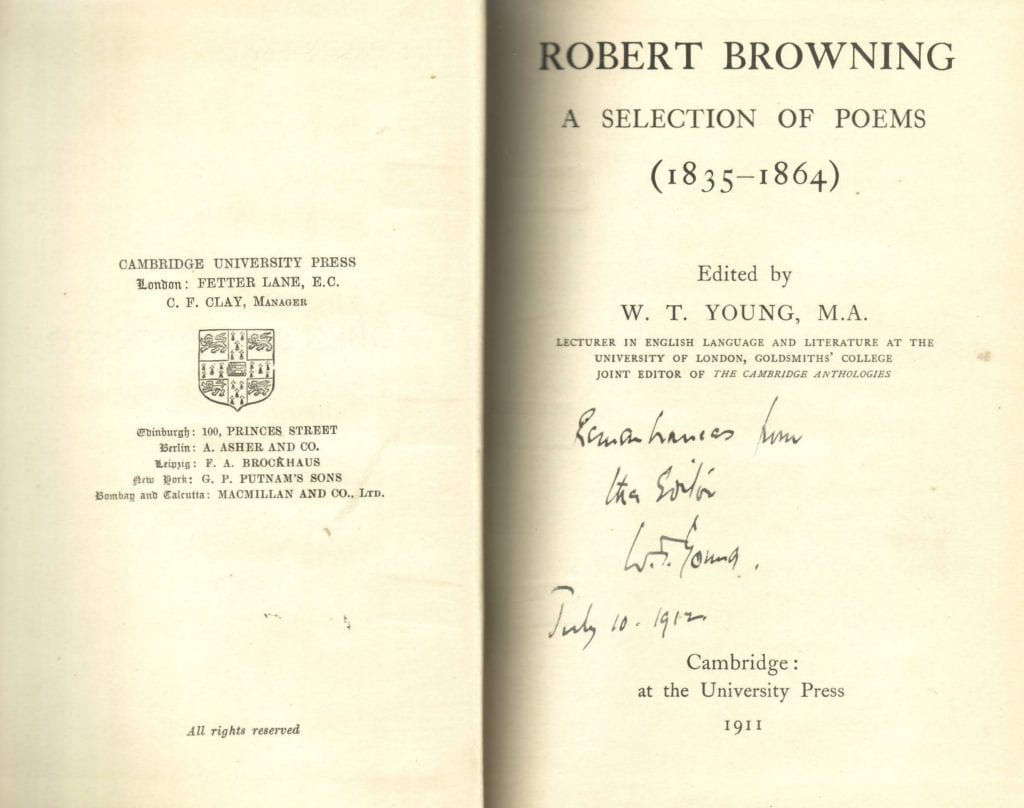

Three of his books, poetry during the age of Shakespeare, the poetry of Robert Browning, and a ‘Primer of English Literature’ had been published by Cambridge University Press and formed the core of the English syllabus in schools and colleges throughout the country.

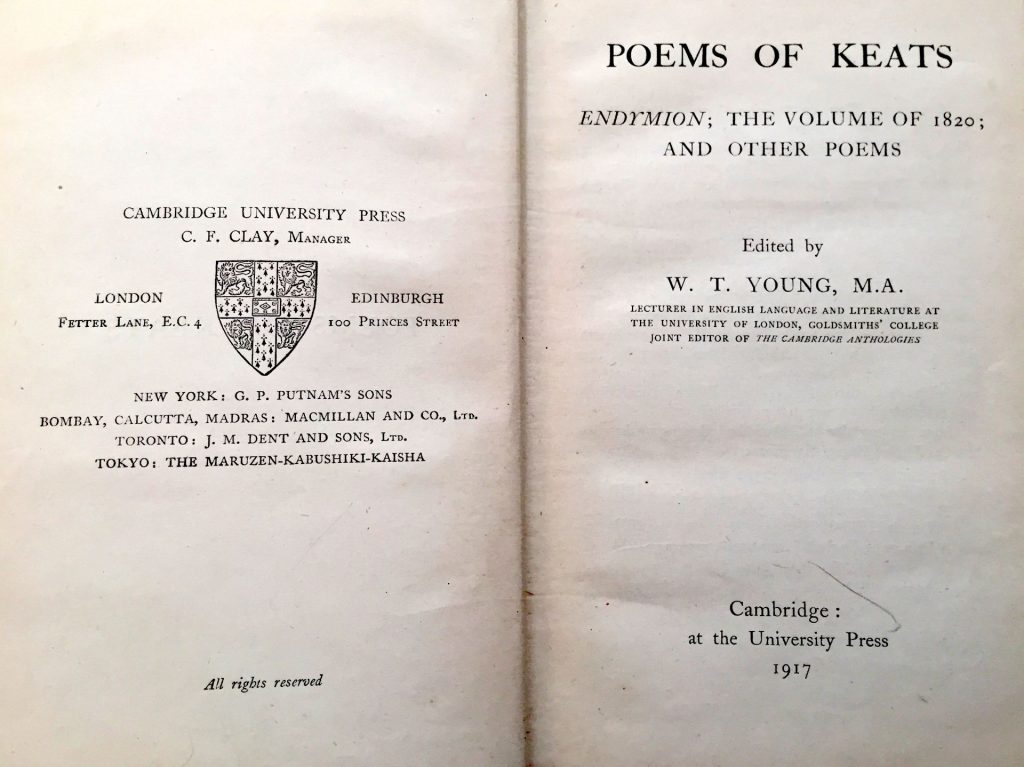

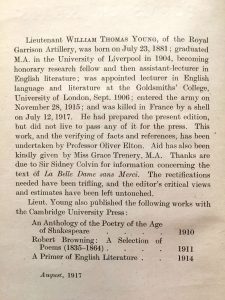

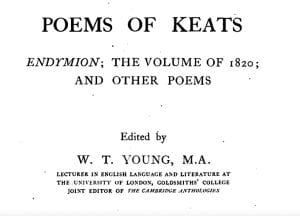

Before he joined up on 28th November 1915, shortly after Goldsmiths’ Warden Captain William Loring had died from wounds inflicted by sniper fire at Gallipoli, he had written most of Poems of Keats: Endymion: The Volume of 1820; And Other Poems.

This was rapidly completed by his mentor at Liverpool University, Professor Oliver Elton, and published posthumously in August 1917 only a matter of weeks after his death.

Lost to History

Researching the lives of the early pioneers of education at Goldsmiths shows how fleeting the notion of significance and memory is in human society.

Very few people have any idea of the contribution of W. T Young BA, MA to the field of English literature.

Yet he was a rising star, and when he died during the relentless battle of attrition that was Passchendaele, Professor Elton would write in the Liverpool Daily Post and Mercury on 25th July 1917:

W.T.Young when 26 years old.

“I have seldom come across a student with a more direct passion for literature in itself as an art, as a reading for life, apart from all the scaffolding, the philological, and historical, that is apt to surround and obscure it. In these studies Young duly equipped himself, but for him they were never the root of the matter. The right spirit, accordingly, was evident in his teaching and writing; he was the straightest and most loyal of colleagues as Liverpool University and Goldsmiths’ can testify? and his going was a loss to our university.

Young produced some very good anthologies from Browning and the Elizabethans, and also a short hand-survey of English literature. His quality, perhaps, can best be judged by turning to the last two volumes of “The Cambridge History of English Literature.” I had been reading his chapters on George Meredith, Samuel Butler (of “Erewhon”), and George Gissing, and on a number of other novelists, when news came of his death.

This is not the place or moment for a review; but it is as well that these pages, the fruit of years and so full of close, fresh thinking, of pointed expression, should be secure within the covers of the monumental “History” and should not go down the stream.”

This is not the place or moment for a review; but it is as well that these pages, the fruit of years and so full of close, fresh thinking, of pointed expression, should be secure within the covers of the monumental “History” and should not go down the stream.”

William T. Young’s portfolio of books are no longer in the College library apart from one copy of the 1910 edition of An Anthology of the poetry of the age of Shakespeare ‘in the reserve stack.‘

Perhaps the Goldsmiths’ copies of his other books had been incinerated in the fires of 1940 and 1971, or simply withdrawn when new academics on the block addressed more contemporary fashions of criticism.

But his students treasured their possession.

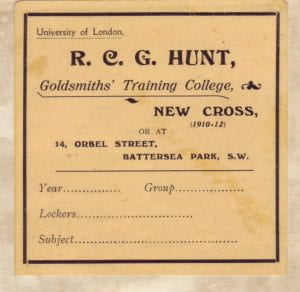

This copy of the anthology of Browning’s poems has the owner R.C.G Hunt’s personal library plate.

R.C.G. Hunt of Goldsmiths’ Training College in New Cross printed his own book plates including his home address at 14 Orbel Street, Battersea Park.

It is also carefully dedicated by William in fountain pen with the words ‘Remembrances from the Editor W.T.Young July 10 1912’ to his student.

Apart from his name being carved on the wooden memorial in the lobby of the Richard Hoggart main building, there is so little trace of how he shaped the critical and literary imagination of hundreds of Goldsmiths’ students and, indeed, the thousands of scholars and teachers throughout the English speaking world who used his texts.

The College’s first woman Vice Principal, Caroline Graveson, wrote in the 1955 College history, The Forge, ‘I have Mr Young’s most promising book on English Literature on my shelves. He was killed in the first war with a career before him in the world of letters.’

Frontispiece of ‘Poems by Keats’ edited by W T Young and published posthumously by Cambridge University Press in 1917. Image: Goldsmiths Archives.

In the college archives, there is a hand-written personnel page setting out his birth and early education in Peterborough, where his father had been a traveling salesman in confectionery.

He had attended Doncaster Grammar school and gained his BA and MA at Liverpool University where he started his academic career as tutor and assistant lecturer during the period 1904-6.

Professor Elton had said ‘bad health had delayed his powers of production’ before his move to Goldsmiths in September 1906, one year after the College’s opening.

His annual salary on joining was £280 (about £23,000 in today’s money) rising in £10 increments to £325 in July 1915 when he left to join the army.

He had been a cadet in the University of London officer training corps, artillery section.

Goldsmiths’ students digging out the rifle range before the First World War where members of the College’s Officer Training Corps could improve their marksmanship.

His entry in the Goldsmiths’ College staff book ends abruptly with the words ‘Killed in France, July 1917.’

The college archives do not have any clearly identified photograph of Mr. Young.

Liverpool University does not have any images of him either.

There are many group staff photographs from the early years, and one from 1909 has a hand-written list below it, but the second and third lines have faded out in places.

Faded Goldsmiths staff photograph from 1909. William Thomas Young is identified front row seat second from left.

A process of elimination and digital electronic enhancement of the faded writing seem to indicate W. T. Young is the male lecturer second from the left sitting in chairs on the front row.

William was short-sighted and wrote in his army documents that he wore glasses.

In other staff line-ups perhaps vanity led him to take off his spectacles and mortar board.

In 1907 William Thomas Young standing second from left, right of his friend Harry Curzon who was head of maths. Woman Vice Principal Caroline Graveson is seated below him, along with the Warden, William Loring, and Vice Principal for men, Thomas Raymont, second and first from right respectively.

Public archives reveal that at the time of the 1911 census William was living at 15 Bloomsbury Mansions in Hart Street WC1 and was hosting a visit of his friend William Loryton Hicks, an assistant secretary at Cambridge University Press.

Hart Street is now Bloomsbury Way and the site is occupied by the headquarters of BUPA.

At the time William was courting 27-year-old Hilda Black, the daughter of the former secretary to the Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon.

She and her family were boarding at 60 to 62 Queensborough Terrace in Paddington and it was in the Paddington district where William and Hilda married towards the end of 1911.

The protesting culture of Goldsmiths’ students as early as 1910-12 during W.T. Young’s time as lecturer. The students are taking part in a ‘Dinner Strike,’ after complaints about the College catering.

Their daughter, Diana Joan, was born 25th April 1916 and her birth was registered in Woolwich.

After her father’s death it would appear she and her mother moved to Southport to live with William’s parents.

William’s War Office file contains a letter of administration whereby his estate of £463, 19 shillings and 11 old pence was held in trust until she was 21-years-old.

Tribute to Lieutenant Thomas Young (who was known as ‘Billy’ to his colleagues and friends) in the posthumously published “Keats Endymion And Other Poems” by Cambridge University Press in August 1917.

William’s surviving First World War officer file also includes a note from his father Thomas, now an Alderman on Southport Council, insisting that the memorial plaque sent to the families of people who died in the Great War, bore his proper rank of first Lieutenant.

William’s grave is tended by the Commonwealth War Grave’s Commission in the Belgian cemetery of Brandhoek and bears the inscription: ‘He gave himself, his all, for freedom’s cause, greatly beloved.’

Passchendaele – a life and morale sapping series of battles in 1917

Photograph Q5723 Imperial War Museums (collection no. 1900-13) THE THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES The Battle of Pilckem Ridge: A British 18 pounder field gun battery taking up new positions close to a communication trench near Boesinghe, 31 July 1917.

Lieutenant William T. Young was commissioned in the Northumbrian North Riding Royal Garrison Artillery and it would seem he would have witnessed or taken part in the Battle of Messines Ridge.

This was a prelude to the Third Battle of Ypres and lasted between 7th and 14th June 1917.

The British final objective was the capture of the ports at Ostend and Zeebrugge from which German U-boat submarines were trying to sink Allied shipping.

The British generals hoped to capture the German positions at Messines by surprise through detonating massive mines set in underground tunnels.

19 of the mines exploded in the early morning of 7th June with horrific casualties in the German lines.

Smashed up German trench on Messines Ridge with dead.’ Photographs from the Haig “Official Photographs” series, National Library Scotland. Licensed under CC BY 4.0

William Young and the men in his ’12 Heavy Battery’ would have heard and felt the explosions viscerally.

The explosions were so loud it was said they could be heard in London.

Lieutenant Young in the Royal Garrison Artillery operated much larger pieces of gunnery than the Royal Field Artillery.

These would include six inch and nine inch bore Howitzers, and 60 Pounder heavy field guns which often had to be pulled by motor tractors and on railway tracks.

William Young’s officer file indicates he died from shell fire on 12th July.

It was in the Ypres salient in 1915 that the German Army had first introduced the evils of chemical warfare to the Western Front.

They started with shells releasing grey-green chlorine gas that blinded allied soldiers and caused many to drown in their own phlegm.

On the 12th of July the Germans experimented with a new yellow mustard gas for the first time.

The French troops called it ‘yperiet.’

It was heavier than air and collected at the foot of trenches.

It would cause the skin of victims to blister, make their eyes very sore, and cause vomiting, internal and external bleeding.

It was insidious in the way it slowly stripped the mucous membrane from the bronchial tubes leading to an extremely painful death lasting four to five weeks.

It is possible William’s unit was shelled as a result of German planes, air balloons, or forward spotters correctly identifying and predicting their coordinates.

He died more than two weeks before the beginning of the Third Battle of Ypres on 31 July 1917.

Legacy and loss

William Young was not the only man of letters in the Royal Garrison Artillery to be lost in the slaughter of First World War.

The journalist, essayist, novelist and poet, Edward Thomas, had been commissioned into the RGA as a second lieutenant and was killed in action soon after he arrived in France at Arras on Easter Monday, 9 April 1917.

The First World War Goldsmiths’ casualties included two members of the teaching staff (Captain William Loring and Lieutenant William T Young), one member of the office staff, 92 teacher training students, and eleven from the Evening and Art Departments.

Professor Elton reflected on the sacrifice that British Society was making when sending its crown jewels of artists, writers and academics into the throes of battle and death:

“It is said the Germans save up and keep back from the front for the sake of the future, their brilliant young men. I do not know if this is true and the policy could be argued. Anyhow, it is not our way, and our way with all its tragedies, with its apparent wastefulness, rests on the conception that the claim for self-sacrifice is nothing less than universal, and that the gap which may follow in the intellectual life and production of the country is self-repaid and is necessary. High now and austere is the cairn rising over the younger scholars and writers, like Dixon Scott and Brooke and Sorley and Young, who have perished willingly – instead of being saved up – for the sake of the future – and whose voices we seem to hear saying:-

But if the old world with all the old iron rent

Laugh and give thanks, shall we be not content?

Nay, we shall rather live, we shall not die.

Life being so little and death so good to give.”

William Young’s study of Robert Browning includes the poem ‘Prospice’ and is marked with the lines:

“Fear death ? – to feel the fog in my throat,

The mist in my face,

When the snows begin, and the blasts denote

I am nearing the place,

The power of the night, the press of the storm,

The post of the foe;

Where he stands, the Arch Fear in a visible form,

Yet the strong man must go…”

William Young analyses the poem from Dramatis Personae published in 1864 and observes ‘it is a poem of fearless self-assertion uttered under pressure of the thought of Death. Shrinking and cowardice are condemned through the two-fold inspiration of the belief in immortality, and the hope of human love to be recovered.’

One wonders if the young father now in uniform in Flanders derived any comfort from this poem he had taught to his students at Goldsmiths when faced with the ‘power of the night’ of Passchendaele’s violence and destruction.

This is certainly the quality of criticism that marked him out as such an inspirational lecturer and literary academic.

Knitted poppies on a wall of Walsham-le-Willows church, Suffolk for Remembrance Day 2017. Image: Tim Crook.

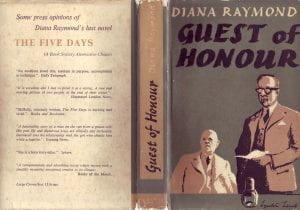

The legacy of his daughter Diana (1916-2009)

William Young’s literary talents were inherited by his daughter, Diana, who was able to go to Cheltenham Ladies College as a result of a grant from the Officers’ Families Fund.

She began writing fiction from the age of 16 ‘sitting in an ABC café in the Harrow Road, London’ according to her obituarist, the award-winning BBC radio feature documentarist Piers Plowright.

Piers also contributed to ‘In memoriam – Diana Raymond’ published in her church’s Parish magazine shortly after her funeral in St John-at-Hampstead church in 2009.

Diana was encouraged in her writing by her enormously successful cousin on her mother’s side, the novelist Pamela Frankau.

Her first novel was rejected by publishers but Pamela urged her never to give up and her second novel, The Door Stood Open, was published when she was only nineteen.

Later in life Diana was commissioned to write a biography of Pamela.

The project stalled when Pamela’s profile waned, but all her papers on the project have been donated to Southampton University’s Special Collections.

Diana published novels under her maiden name before marrying the influential novelist Ernest Raymond in 1940.

By the time of her death in 2009 she had completed 24 novels described by Plowright as ‘infused with wit and metaphysics.’

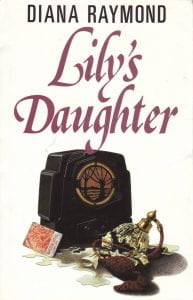

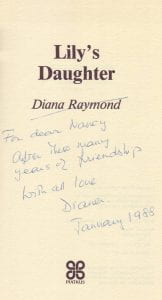

It is likely that the sense of loss caused by her father’s death is an autobiographical theme running through Lily’s Daughter, first published in 1988 and reissued as an ebook by Corazon books in 2014.

Her husband Ernest helped trace her father’s grave in the Brandhoek cemetery so she could visit his final resting place for the first time.

Frontispiece to the posthumously published volume of Keats’ poems edited by W.T. Young before his death by artillery bombardment in 1917.

Her father’s posthumous work on Keats coincided with her own love for the poet.

She was inspired to write the play ‘John Keats Lived Here’ to mark the bicentenary of his birth which was  performed by the Hampstead Players in 1995 with a one night performance in the West End.

performed by the Hampstead Players in 1995 with a one night performance in the West End.

When re-reading her father’s introduction to his Keats’ anthology she said: ‘the echoes there of my own love for Keats are comforting, like a hand held out across time.’

Research on Diana Joan Raymond by Mary Davies, Head of Alumni Relations and Regular Giving.

That’s So Goldsmiths– a forthcoming history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.

Goldsmiths History Project Podcast by Professor Tim Crook