Parliament Square statue of Sir Winston Churchill by Goldsmiths College’s Head of Sculpture Ivor Roberts-Jones. Photo by Eluveitie – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

It was the worst day of their lives.

That was the sense of emotional and professional disaster for Goldsmiths Art School alumni Graham and Kathleen Sutherland in 1954.

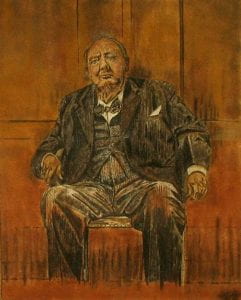

The Prime Minister Winston Churchill had sent round his official limousine with a letter furiously rejecting the portrait of him that Graham had been commissioned by Parliament to paint.

Winston had thundered:

“…there will be an acute difference of opinion about this portrait…it will bring an element of controversy into a function that was intended to be a matter of agreement between the Members of the House of Commons where I have lived my life … the painting, however masterly in execution, is not suitable…”

This was Parliament’s gift to celebrate the eightieth birthday of Britain’s war-time leader between 1940 and 1945.

Its unveiling a few days later in Westminster Hall would be another catastrophic humiliation for the Sutherlands; this time played out live on BBC television and reported in newsreel cinemas.

The irascible statesman, having been persuaded to avoid publicly rejecting the gift, used sarcasm to twist the knife into the portraitist he believed had made him look like a decrepit old man:

“…the portrait [turning to look at it] is a remarkable example of modern art. [Haughty laughter as well as applause] It certainly combines force and candour. These are qualities which no active member of either House can do without or should fear to meet.”

Further Pathe footage of Winston Churchill’s Westminster Hall 80th birthday ceremony 1954. Click through to view.

The tragedy of this event has been the subject of a book and a high profile television documentary series written and presented by the historian Simon Schama and, more recently, an entire episode of the Netflix television drama series on Queen Elizabeth II, The Crown.

Graham and Kathleen met each other when they were art students at Goldsmiths College between 1921 and 1926.

The Blomfield block built with funds provided by the Goldsmiths Company between 1905 and 1907 for the Art School where Graham Sutherland and his future wife Kathleen Barry were students in the early 1920s.

Their encounter at Goldsmiths is one of many romantic and charming love stories in the history of the College.

At first they would simply gaze at each other in wonderment during life drawing classes unable to say a word.

In July 1921 the ‘chat-up’ ritual involved passing onto her a written invitation to the Diaghilev ballet.

It was not until the rendez-vous at Charing Cross station that they actually exchanged words for the first time.

Kathleen recalled:

“I remember I was very surprised at the timbre of his voice, being so high and light, like the Duke of Windsor’s. It was all very agreeable, and he had to borrow half a crown to get his train home.”

The third floor studios of the Blomfield Art School block where Graham and Kathleen studied etching and other crafts between 1921-6.

Graham Sutherland initially established his reputation as an engraver, sometimes earning £700 in sales in one year, but the international market collapsed with the 1929 Wall Street crash.

Goldsmiths’ Art School had begun in 1891 before it became part of the University of London in 1904-5.

The intention was that it should pursue the higher education of art, concentrating on painting, modelling and design and avoiding crafts ‘conducted along trade lines.’

One distinction of the school, according to a previous College historian A.E. Firth, is that for many years: ‘very few of its students took any examinations at all, or received any nationally recognised qualifications at the end of their courses.’

This was the case with Graham and Kathleen.

‘Pedestal Table in the Studio’ 1922 by André Masson 1896-1987 Bequeathed by Elly Kahnweiler 1991 to form part of the gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, accessioned 1994. Surrealism was not on the curriculum of Goldsmiths’ Art school between 1921-26.

During their time in New Cross, Graham recalled that if they sought inspiration from modernism or any pioneering ideas in contemporary art movements, they had to find that in the galleries and exhibitions of Central London and Paris:

“While the teaching at the school was sound and was certainly practical, it was totally out of touch with the great European movements, then in full flower and moving to a climax. If Old Masters’ names were heard I do not remember much serious attempt being made to implant any real understanding of the significance of their work. Still less were we really taught to apply their example to our own work. I do not remember hearing a word about the Impressionists and on the subject of the Modern Movement there was profound silence.”

It was in the 1930s that he developed as a painter mixing a continental modernist influence with the English romantic tradition.

His etching ‘Pastoral’ from 1930 was significantly referred to in the dialogue of the episode ‘The Assassins’ from the Netflix series ‘The Crown’.

The scriptwriter dramatised a sense of sympathy between Sutherland’s grieving over the death of his 2 month old son, John, in 1928, and Churchill’s profound sadness over the death of his 2 year old daughter Marigold in 1921.

It is suggested ‘Pastoral’ shares an undercurrent of personal despair with Churchill’s repeated attempts to paint the pond at his home in Chartwell.

Sutherland further developed his reputation as a home front War artist between 1939 and 1945.

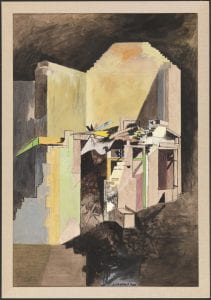

He produced a haunting series of images of the impact of the blitz on domestic life that he titled ‘Devastation.’

Devastation, 1941: An East End Street 1941 Graham Sutherland OM 1903-1980 Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee 1946 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N05736

- Devastation, 1940: House in Wales. Graham Sutherland OM 1903-1980 Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee 1946

- Devastation, 1940: The City a fallen lift shaft (Art.IWM ART LD 893)

- Furnaces-Slag Ladies 1942: (Art.IWM ART LD 1773)

- Devastation, 1940: A House on the Welsh Border 1940 Graham Sutherland OM 1903-1980 Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee 1946 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N05734

- Devastation, 1941: East End, Burnt Paper Warehouse 1941 Graham Sutherland OM 1903-1980 Presented by the War Artists Advisory Committee 1946 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N05737

Edward Lucie-Smith said that it was ‘Sutherland’s arresting image of the writer Somerset Maugham, painted in 1949, followed by the equally arresting full length [portrait] of Lord Beaverbrook, started in May, 1951, that made him the most sought after portrait painter of his time.’

Edward Sackville-West wrote the introduction of the Penguin Modern Painters’ volume on Graham Sutherland in 1944.

This placed him in the frame of leading contemporary artists and Sackville-West had no hesitation in comparing him with Henry Moore:

“It is not only that, in excellence of technique and invention, they are two of the most significant artists of our time; they possess as well, the unmoved, receptive eyes which alone can reflect the tragic idyll of contemporary England.”

Graham Sutherland was offered the Churchill commission because of the recommendation of the left-wing Labour MP Jennie Lee.

Somerset Maugham 1949 Graham Sutherland OM 1903-1980 Presented by Lady John Hope 1951 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N06034

And this may have been the source for what became the schism in what initially developed as a warm friendship between Winston and Clementine and Graham and Kathleen.

‘Wow’, wrote Lady Churchill to her daughter in law, ‘He is really a most attractive man.’

Winston relished being painted by a fellow artist and enjoyed joshing him over his socialist allegiance.

Sutherland recalled the Prime Minister throwing rather expensive food into the goldfish pond:

“I would say ‘But the ones at the back aren’t getting anything at all, you’re just throwing it in the front,’ And he said: ‘Well, that’s life, you see. We can’t all be communists, we can’t all be equal.”

There was always underlying tension beneath the surface of polite acquaintance.

Winston was so taken with Kathleen’s beauty that he expressed his intention and wish to paint her portrait.

He did not know that Graham was telling Kathleen that he thought Churchill’s paintings ‘very nearly first-rate, but had a touch of vulgarity about them.’

Sutherland failed to appreciate how important it was that Churchill needed to be a more consultative participant in the creation of his own portrait.

He felt excluded and discomforted by Sutherland’s determination to paint what he saw rather than how Churchill wished to be represented.

He would demand ‘How are you going to paint me? As a cherub, or a bulldog?’

In the end Sutherland saw more of the bulldog and lion at bay – a role that Churchill’s longstanding doctor Lord Moran tried to warn him was simply one of his performances.

One irony is that Winston’s defiant lion and bulldog pose was often captured by photographic and electronic media, and its inclusion in a 1965 film obituary by Pathe bears a striking resemblance to Sutherland’s controversial portrait.

Churchill as ‘defiant bulldog’ in ‘This Was A Man’ Tribute To Sir Winston Churchill (1965) Pathe. Click through to see the film.

When Churchill finally got to see the painting, it was too late. What he saw was:

“Sitting on a lavatory … It makes me look half-witted, which I ain’t … Here sits an old man on his stool, pressing and pressing … I look like a down-and-out drunk who has been picked out of the gutter in the Strand.”

The guffaws of laughter cued by Churchill’s quip about modern art at Westminster Hall struck Graham Sutherland very hard.

BBC live footage shows Graham Sutherland holding his hand to his face in apparent shock and mortification.

At the same time, a freeze-frame of Churchill’s countenance from the Pathe newsreel report indicates mischief and cunning.

Admiration and dislike for the portrait divided along party lines.

Lord Hailsham was scathing:

“I’d throw Mr Sutherland into the Thames. The portrait is a complete disgrace. It is bad-mannered.”

Sutherland had to walk past official guests complaining that their beloved statesman had a dirty face and openly expressing their feelings that a terrible tribute had been paid to one of the country’s greatest men.

In another age Sutherland as the courtier artist who had outraged the King, would have found himself on the scaffold.

In the middle of the twentieth century such trial and retribution was more socio-psychological.

A storm was to rage in the pages of the national press and the Churchill family would decide that the painting, rather than its creator, should be consigned to a bonfire of retribution.

What was supposed to have been a gift to the nation that would hang at Westminster after Churchill’s death was crated up and destroyed on Clementine’s instructions within the year.

Winston and his loyal family were not in a position to appreciate that Graham Sutherland had created a beautiful expression of Churchillian indomitability, a symbol of an old country’s defiance of all the ravages of total war, and a presentation of the sturdy and independent humility of a democratic Parliamentarian in plain dress.

Like his series of paintings from the Blitz, this was the climax of the devastation of survival, and indeed, victory.

One of Sutherland’s biographers, Roger Berthoud concluded: ‘Graham had seriously underestimated his sitter’s sensitivity. As a portrait, his work was masterly; as a gift, it was a dismal failure.’

Graham Sutherland said it was vandalism, but Clementine had been determined to protect her husband’s feelings.

Simon Schama explained that Winston had not wanted a painted obituary.

He also said:

“With the exception perhaps of the paintings of the Duke of Wellington by Goya and Thomas Lawrence, Sutherland accomplished the most powerful image of a Great Briton ever executed.”

This national treasure now only exists as photographs and the sketches the artist made in its preparation.

There have been noble attempts to resurrect the painting.

Aster Crawshaw & Alistair Lexden have detailed the painstaking reproduction of Sutherland’s lost portrait by Albrecht von Leyden – a great admirer of both the original artist and subject.

Crawshaw and Lexden report that this courageous rebirth of Sutherland’s Portrait of Churchill was donated by von Leyden to the Carlton Club:

“It was Albrecht’s hope that the portrait would be hung in the Club’s Churchill Room. A photograph, taken apparently soon after its arrival, shows the portrait on the wall of another room. It was then stored in the Club’s attic where it remains.”

- Sir Winston Churchill by Brian Pike CC BY 3.0

- Albrecht von Leyden’s recreation of Sutherland’s portrait 1981

Many years later Lady Clementine Churchill would not be so hostile to another expression of a Goldsmiths artist’s imagination in the representation of her husband.

Architectural detail of the Arts building, designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, completed in 1907 and situated at the back of Goldsmiths College main building.

Ivor Roberts-Jones (1913-96) was both a student and lecturer at Goldsmiths and eventually became head of sculpture in the college’s Art School (1964-78).

In 1971 he was invited along with eight other sculptors to submit maquettes for a potential statue of Churchill to be erected in Parliament Square.

None were thought suitable. Roberts-Jones and one other artist were asked to submit again.

This time round Ivor made two models.

One was similar to his first submission with Winston Churchill in robes.

The other was awarded the commission.

This was a more sturdy and pugnacious figure similar to the famous war-time photograph of the Prime Minister in long coat standing among the ruins of the House of Commons in May 1941 digging his cane into the rubble.

It replicated the image of Winston with his left hand thrust into his pocket, jaw jutting outwards, grim-faced and with a posture of steely defiance.

Roberts-Jones had made his reputation with sculptures of the prominent figure of Augustus John in his home town of Fordingbridge, and the reflective looking head of Yehudi Menuhin.

Ivor Roberts-Jones statue of Winston Churchill. Photo by David Holt from London, England – London 068 Parliament and Churchill, CC BY-SA 2.0

The Churchill statue, cast in bronze, cost £30,000, and met the full approval of Lady Clementine who enthusiastically unveiled it with the Queen in 1973 at its prominent position in Parliament Square facing Big Ben.

Unlike Sutherland’s infamous painting, this impressive public work of art by a Goldsmiths artist has survived.

However, it might be argued that rioting in Central London on May Day 2000 challenged the dignity of Churchill’s stature when its head was dressed with a green mohican of turf cut from the grass in the square.

The figure was also made to look as though blood was dripping from its mouth and graffiti was sprayed on the plinth.

A student from Cambridge, studying English and European literature, was jailed for 30 days.

He said he wanted to express a challenge to an icon of the British Establishment, but the Magistrate told him the statue symbolised to many people the war effort and the struggle against the Nazis.

Ten years later the statue plinth was subject to further defacement in student protests covered by the media.

These events are a reminder that public art will always be a matter of politics as well as culture.

At Goldsmiths art, politics, culture and society have frequently been an enduring combustion of controversy and protest.

And we are left with the poignant legend of the finest portrait of a British leader ever painted not surviving the conflagration.

By Professor Tim Crook, Goldsmiths historian

Sources

Anon, ‘Sculptor for Churchill’, London: Illustrated London News, page 12, 27th March 1971

Berthoud, Roger, Graham Sutherland: A Biography, London: faber & faber, 1982

Chesterman, Ross, Golden Sunrise: The Story of Goldsmiths’ College, 1953-1974, Durham: The Pentland Press, 1996

Crawshaw, Aster & Lexden, Alistair, ‘Homage to a Hero and a Masterpiece: The Destruction and Rebirth of Sutherland’s Portrait of Churchill’, London: The London Magazine, pages 25-42, June & July, 2016

Dymond, Dorothy ed., The Forge: The History of Goldsmiths’ College 1905-1955, London: Methuen & Co., 1955

Firth, A. E., Goldsmiths’ College: A Centenary Account, London: The Athlone Press, 1991

Lucie-Smith, Edward, ‘A Visionary At The Tate’, Illustrated London News, pages 64-5, 1st May 1982.

Sackville-West, Edward, Graham Sutherland, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1944

Schama, Simon, The Face of Britain: The Nation through Its Portraits, London: Viking, 2015

That’s So Goldsmiths, a new history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.

Goldsmiths History Project podcast by Professor Tim Crook