Content note: this post contains mentions of domestic violence and suicide.

I first encountered Prem Chandra when I worked on a display of her husband Avinash Chandra’s work at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge in 2019. I was looking through Avinash’s artworks in the attic of Kettle’s Yard, when I found a screenprint in sunset-hued paint on black paper, featuring Avinash’s signature conglomeration of snake-like and ovular forms. In the left margin, there was an inscription in white pencil reading ‘Jim + Helen [Ede, founders of Kettle’s Yard] – Greetings – Happy New Year – from Prem – Avinash – Alita – 64’. I was intrigued by the mention of two women’s names, Prem and Alita. At the time Saidiya Hartman’s book Wayward Lives Beautiful Experiments had just been released and was in my head. I took Hartman’s endeavour to imagine the ‘everyday anarchy’ of early twentieth-century Black women, in order to ‘press at the limits’ of archival documents, as permission to radically speculate about Prem and Alita. Who were they, and what was their relation to Avinash? At first I read the inscription symmetrically, assuming that Prem and Avinash were married like Jim and Helen, and that Alita was their child. Having deduced that the inscription was in Avinash’s handwriting – since it corresponded to his signature on other works in the Kettle’s Yard collection – I wondered why he had written Prem’s name before his. Was it a gesture of humility – akin to that effected in the phrase ‘my better half’, or, more ambiguously, ‘the boss’ – or was it a subtle attribution of authorship?

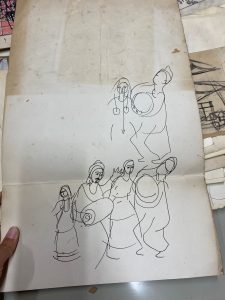

I learned more about Prem Chandra in December 2022, while conducting research in Avinash’s archive on Indian artist collectives in 1960s–80s London. Amid the mass of ephemera was an empty manila envelope marked ‘Prem’s drawing’, again in Avinash’s handwriting, revealing that she had made art. I then found an ink drawing of veiled and turbaned figures playing musical instruments, which doesn’t resemble Avinash’s drawings, and may be traceable to Prem.

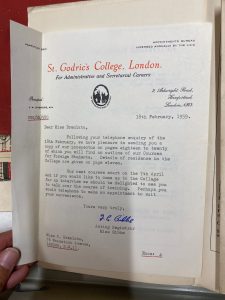

I also found a letter dated 18 February 1959 – posted to the house she shared with Avinash at 76 Woodstock Avenue in Golder’s Green – responding to Prem’s request for a prospectus for courses on administrative and secretarial training for foreign students in London. This told me where she lived, and that she was exploring the limited possibilities for an Indian woman in 1950s London to earn a living.

Avinash’s former gallerist, who now keeps his archive, filled in the gaps for me: Prem’s full name was Premlata Chandra, and she was an artist. She and Avinash left India in 1956 to establish their artistic careers in London, where Prem faced bleak prospects of commercial success. Reflecting the broader culture of misogyny and machismo in Indian modernist circles in London, if not modernism at large, Avinash grew jealous, controlling and violent towards her, including stopping her from practising as an artist. Eventually Prem and her daughter went back to her family home in India, where she died shortly afterwards.

To ask ‘who is Prem Chandra’ is to shake the foundations of art history. Prem’s story, and how it is represented in the archive, demonstrate the scale of patriarchal pressure on an artist’s life, practice and historicisation. Although feminist and decolonial critiques of modernism are now widely accepted in the discipline, and work is underway to recover artists excluded from a patriarchal and colonial canon – including the recent exhibitions Helen Saunders: Modernist Rebel at The Courtauld Institute of Art and Althea McNish: Colour is Mine at the William Morris Gallery and Whitworth Art Gallery – Prem’s obscurity shows us the distance we have yet to cover.

It is significant that I first came across Prem in the Kettle’s Yard attic, where Avinash’s works were kept as part of the Student Loan Collection, an initiative running since 1957 to lend students artworks to hang in their rooms. The Student Loan Collection is also an index of the lower-value work in the Kettle’s Yard collection, and as such is housed in the attic rather than in the newer, professional art store, or on the walls.[1] This gets us to the heart of the problem: if Avinash’s work is relegated according to a metric of artistic value rooted in European aesthetic philosophy, which reserved genius for white artists and positioned the colonised other as incapable of producing anything but naïveté or barbarism,[2] and if Prem suffered additionally from patriarchal suppression of creative activities, then she is the shadow of a shadow in art history.

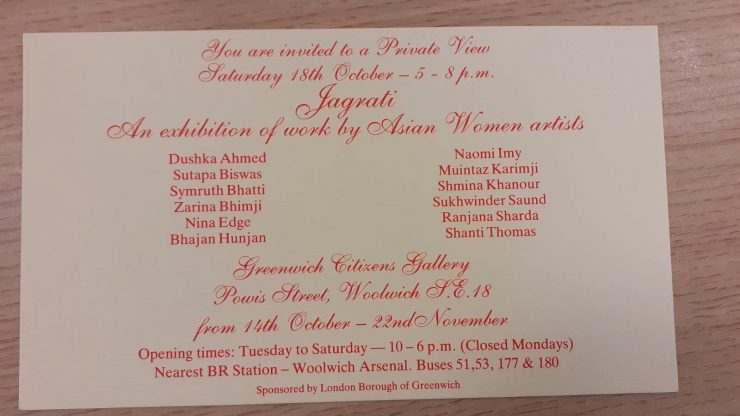

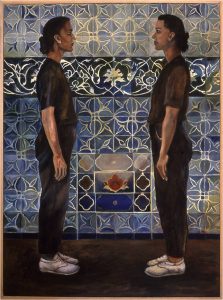

If this blog post calls for anything, it is for recovery work to defy the logic of Prem’s double exclusion by ideologies of race and gender. Rather than assessing Avinash’s contribution to art history, and then undertaking a deeper excavation to recuperate his wife – which would follow the still persistent pattern of secondarily treating artists who bore the brunt of race and gender – let’s analyse them at the same time. Let us put into practice the now established understanding that race and gender are mutually constitutive. It is high time that we expand existing work on international modernism to appreciate the significance and critique the masculinism of Indian modernists in Britain – such as Gajanan Bhagwat, Balraj Khanna, Yashwant Mali, S V Rama Rao, Lancelot Ribeiro and Ibrahim Wagh, who staged the exhibition Six Indian Painters at India House in 1964 – as well as the women who received less recognition then and now for building art worlds with them. Prem Chandra is merely a starting point in this project, which must also include the painter Fatima Ahmed, who exhibited at Five Contemporary Indian Artists at The India Tea Centre, London in 1976, as well as Maria Souza, the fashion designer, gallerist and network builder who ran Gallery 38 on Homer Street from 1975–85 as ‘an international gallery for unestablished artists’.[3] To tell their histories, and explore how they exert pressure on the categories ‘artist’, ‘history’ and ‘archive’, is to begin securing ‘epistemological justice’ for the women who struggled to live as artists under patriarchy in the former colonial metropole.[4]

This blog post emerges from conversations with David Ewing, Peter Osbourne, Symrath Patti, Sarah Carne and Dr Amy Tobin, to whom I extend my sincere thanks.

[1] Avinash Chandra’s works have subsequently been moved from the Kettle’s Yard Student Loan Collection to the Loan Collection.

[2] See for instance Partha Mitter’s Much Maligned Monsters (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977)

[3] See Naseem Khan, ‘Interview with Maria Souza’, Bazaar no. 3, Winter 1987, p. 17.

[4] Gurminder K. Bhambra, ‘Decolonizing Critical Theory?: Epistemological Justice, Progress, Reparations’, Critical Times, Volume 4, Issue 1, April 2021, pp. 73–89.

For further information please see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avinash_Chandra