Artist and filmmaker Holly Antrum reflects on her recent artwork Markéta’s Notes, which featured in the exhibition ‘Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen: Intersections in Theory, Film and Art’, curated by Oliver Fuke and Nicolas Helm-Grovas at Camera Austria in Graz. She has been working in a TECHNE-AHRC funded collaborative partnership between Kingston School of Art and the British Film Institute for her practice-based PhD.

An audio version of this blog post can be listened to here:

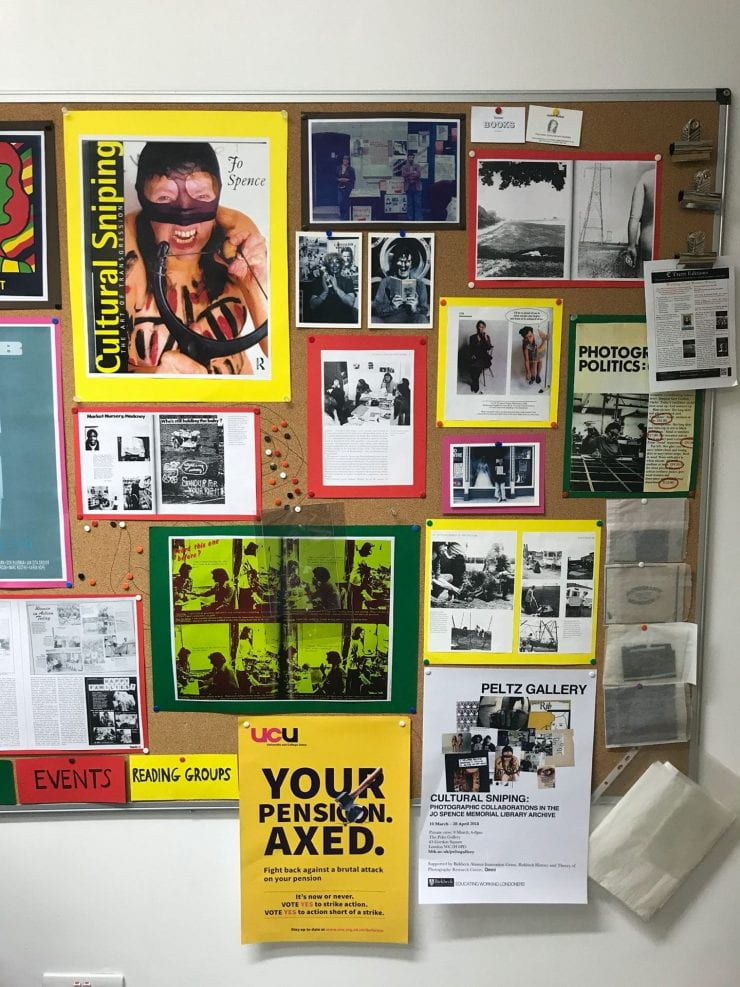

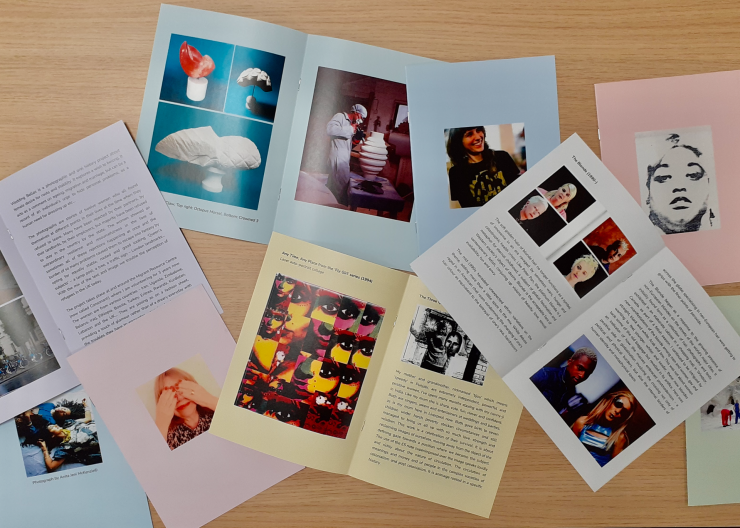

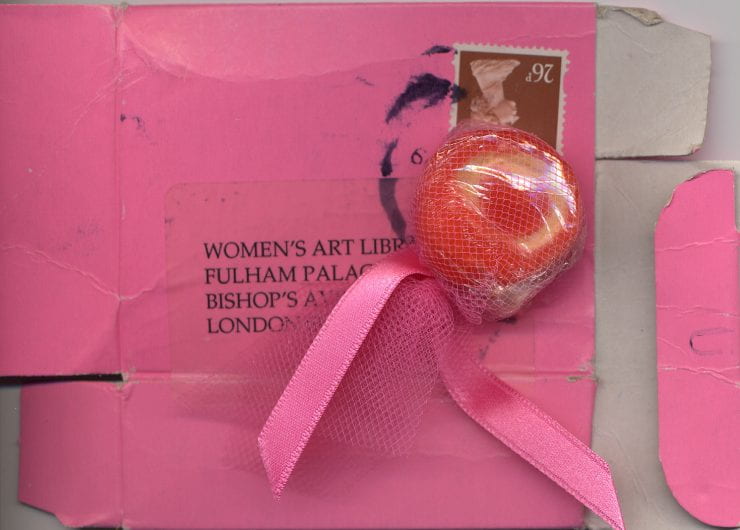

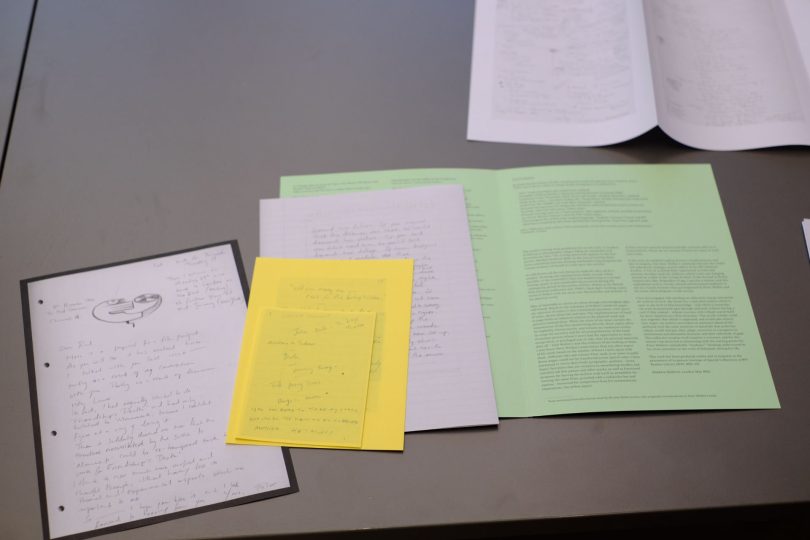

As a collection of papers, Markéta’s Notes is an artwork encountered on a display table, but which can also be handled as a folder and read up close or taken away from the exhibition. It can be read selectively in relation to the surrounding curation or read by itself and may eventually guide the reader back to the BFI National Archive. Visitors in Graz won’t know much about Markéta, but it is apparent that the notes are a reproduction of a set of copies produced from viewing Peter Wollen’s handwritten originals at the BFI Special Collections viewing desk in London. As a contribution to the exhibition that includes well known works by Laura Mulvey and Wollen, as well as intersecting artworks by other artists, Markéta’s Notes can function in two ways. The first is the most basic, that they highlight and widen access to Wollen’s archived notebooks through having been copied from them (the anachronism of longhand evading the copyright of the scanner or lens as an adaptation of the original – though duly approved by the donor of the Wollen collection). The second being that Markéta’s Notes operate at the level of an autonomous artwork that problematises the manifestation of what we see: that this is all situated inside a fiction, or conveyed by the hand of not me, but a fictional name, who has translated that encounter physically onto a new page – and then left the archive with the copy. Inside the stationer’s mint-green folder, Markéta’s voice is presented broadly stating her process, time and place, observations about material edges, expectations about handling the six copied documents inside, as well as alluding to something utopian, and detached from the practical aspects of navigating large collections. She says: ‘My dream for a state film archive which is open to any level of film knowledge […] An archive networked on sentience ahead of the authorial, with the same attention to materials that archivists imbue, would […] transgress its mainstream and alternative histories and their infinitude of gaps’.

Markéta’s Notes (2019-22), are part of an ongoing artist filmmaking and writing project that explores the formation of a fictional narrator, a researcher, and invests an interest in an idea of the self, a reader, in her subjective movement across archival material and in place of the formal structures that govern the archive. As a long-term project, the practice absorbs a contemporary and real set of limitations (the restrictions of the pandemic, the rules and contingent permits of the archive and a fluctuating pattern of being up close in the archive or in an interview to being entirely removed from the subjects themselves). The practicalities that inform the project also include shadowing an archivist and asking questions, prioritising those crucial interpersonal means of looking into an archive. It also requires holding onto reflections about the state of mind attached to archival research – for example we might be interested in more than one thing and in disconnected things simultaneously. In a sense, drawing on observations of the layers of archival encounters is an attempt to side-step canonical knowledge (and even subject-vocabulary, both of which we are perhaps supposed/assumed to already hold when we enter the archive). The publication Markéta’s Notes offers an entry point and set of signposts that begin to reflect the passage of Markéta’s attention through her research, and her later voice upon it. Her voice is also an interpersonal construction – researched in another corner of my project through oral history interviews with a small group of Czech women born in the mid–late 1970s, with a personal interest to develop the subjectivity of a daughter of my mother by a different turn of history and thereby potential history. In a fictive, reality-rooted space, Markéta’s Notes layers and traverses multiple narratives and is propelled foremost by the human and interpersonal labour of archives and memory-keeping.

At the beginning of the project, the conversations I had with the BFI Wollen archivist, Wendy Russell, highlighted Wollen’s recent presence in the collection. Their status and attached tasks I found interesting. The Wollen collection was then (and still is) uniquely and powerfully indeterminate within the superstructure it is becoming housed in for perpetuity. I feel that this changes once accessions are settled into the overall index. The status of ‘being catalogued’ within the BFI enabled a timely viewpoint to rethink my interactions with the search interface of the BFI, observing that it dictated much of how and what we can reach towards, drawing on a profile of what one might already know. The Wollen collection thereby eluded the search interface and categorised identity. It signified materials that one might spend time with alone, but on other days are being condition checked, that are changing in hierarchy and ID number, and may be in a different place (or even site) next time one visits – this transition status of ‘becoming’ seemed to invite a response. To respond with developing a fictional consciousness amid working within the ‘Scripts Documents and Ephemera’ section of the BFI National Archive also offers a way to engage through practice with the narrations appearing on paper from Wollen’s own films and in his scriptwriting – also centring the archived object and its present context.

Drawing on the arguably encyclopaedic aggregation of film and cultural references existing within Wollen’s notes, I have sought to create a sample in Markéta’s Notes, to invest these notebooks with the speculative utility of an alternative collection catalogue – albeit a loose and haptic idea of a system of reference within a journey of research. The project is rooted in recent precedents such as the mythopoetic adaptations of reality that David Burrows and Simon O’Sullivan’s term ‘fictioning’ invites of contemporary art practice, and commissioned projects such as the 37 curatorial and artistic experiments that made up the Arsenal’s Living Archive Project centred on the 50 years of that film archive in Berlin in 2013. It also bears in mind the influence that theoretical, reparative worldmaking projects such as Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s Potential History could have on fictioning notes were it to evolve into a template available to a range of different subjectivities through a decolonial research collective working out these different routes, and embarking on the ‘unlearning’ that could be activated through a national collection.

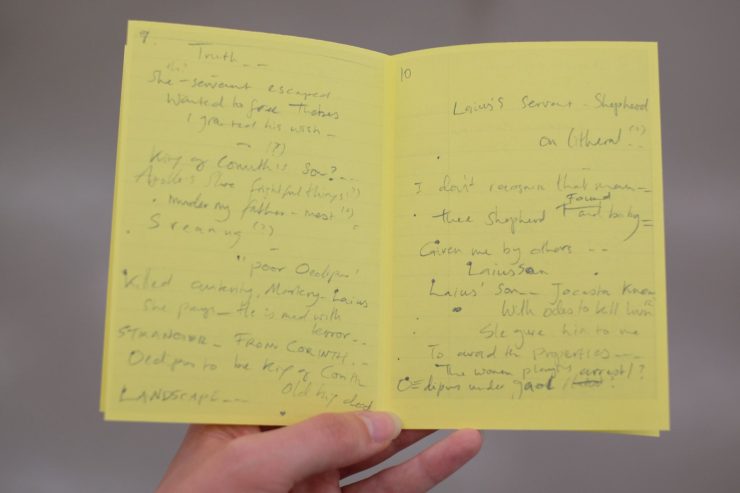

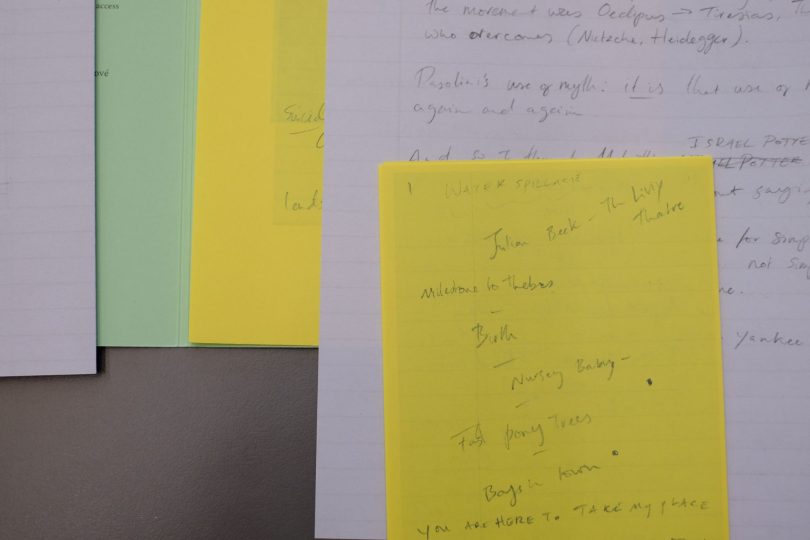

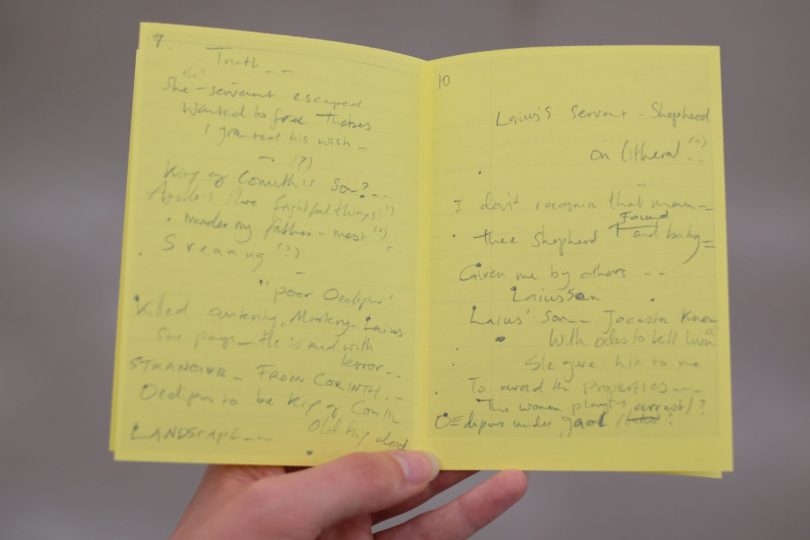

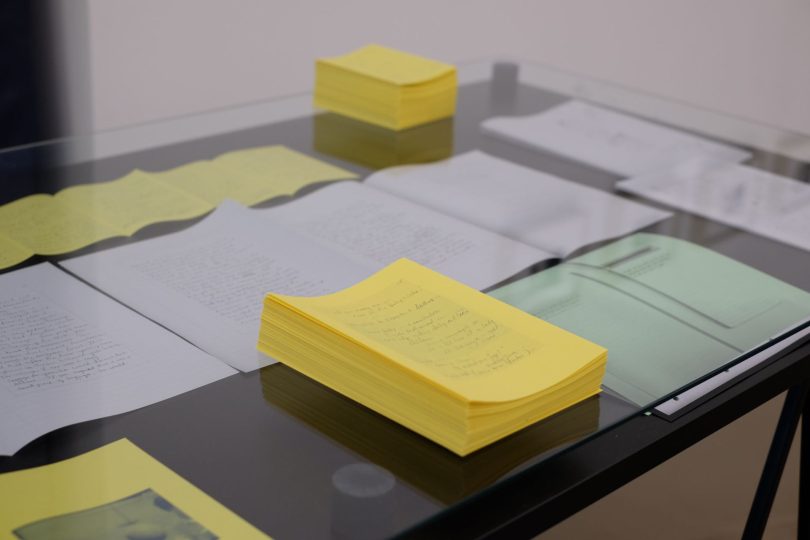

Coming back to the project as an artist’s multiple, historians of Peter Wollen can only use Markéta’s Notes to act as a mediated prompt which observes the lost ‘purity’ of something live within the archival encounter for oneself. Instead, a sample is shared from a previous encounter, with facsimiles that are ambulant and inexact. They instead encounter the facsimile, the intensity of Markéta’s study amplifying the time held within the personal tool of the notebook. There is an encompassing engagement with the schemata of notebook pages to reflect a material form of liveness (and perhaps obsessiveness) condensed in the archive. The schemata of Wollen’s notes occurs most clearly within one kind of note-form selected for the reproductions – that of film viewing notes (reproduced on yellow paper as a nod to Wollen’s use of yellow legal notepads, as was also typical of some film reviewers in the pre-internet era). And there, with a cue to a selection from a wider quantity of such notes, we see some of what was momentarily important to Wollen as he watched the films (here, Pasolini’s Oedipus Rex in full and a sample section of British kitchen sink dialogues from Tony Richardson’s A Taste of Honey). His captions on the films are vivid and express the brevity of notetaking and the passage of dialogue from screen to page. Parts of the notes are illegible, but every available mark has been copied, just without copying the original handwriting. The interference of Markéta might be forgiven, as she allows this information, or these narratives, to travel out from the archive, an almost adolescent subversion of the rules. In the gallery these yellow notes are presented as a pile of free concertina leaflets suggesting the opportunity to watch the films ourselves and compare our impressions with his, while other contents of Markéta’s Notes are distinguished for different modes of reading and sit below a glass tabletop – although readers may note the folder says ‘Please do not attempt to keep my copies in such strict ways’ – as well as the historical permutations of Benjamin’s foundational text The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction for the media invoked there and mirrored here, including the stranding of the camera.

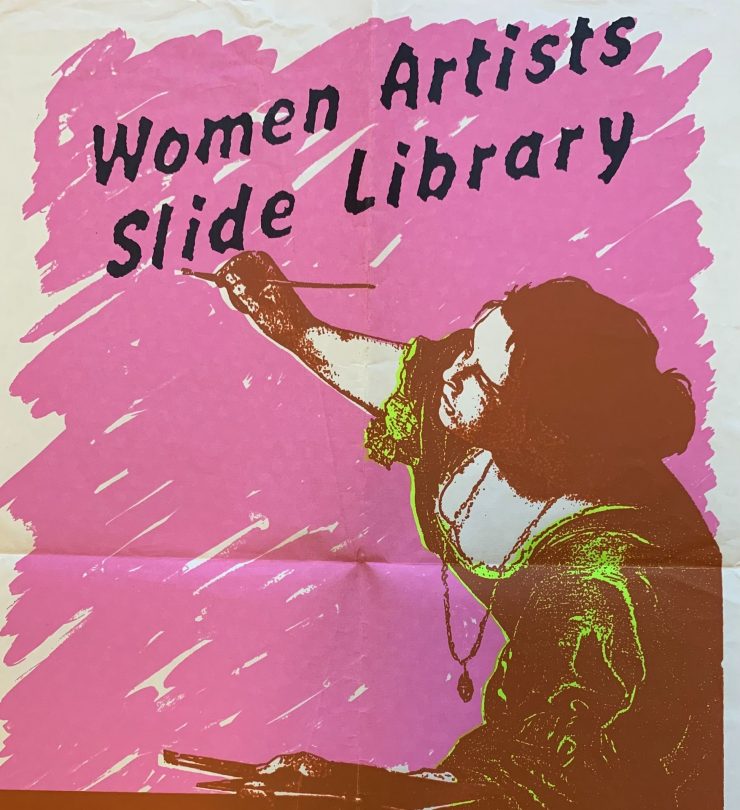

Turning to real-time marks rather than using a lens, Markéta has the desire to use Wollen’s notebooks (because, she says, of his proximity to feminism during his life, though paper-habits and a material attraction of one notebook user to another might also be observed in the work). From Wollen’s lists, references, drafts, conference notes and screenplays, the researcher is poised to depart into other parts of the archive – a Borgesian fiction of excess which would be impossible to complete but which Markéta very loosely and humbly attempts through diagrams and new lists, standing back to see what is emerging. A filmography derived from looking through the files of Wollen’s film notes appears in Markéta’s Notes on the inside cover.

I am still working out why Markéta is interested in Wollen and allow for a misalignment of histories as well as the scope for misreadings that do occur, quite literally, where handwriting is concerned. What may be most useful to think about in publishing Markéta’s Notes is how feminist projects (be that in subject, methodology or both), here including fictioning, might decontextualise their use of archival materials to reorient ourselves within the patriarchal history project of the archive. By a provocation drawing on and linking three areas of learning and critique: subject, reader and architecture, these happen to reflect some of the productive impositions that artist research can entertain and juxtapose.

Embedded to a certain degree within the institution, this project will always struggle to fulfil some of its more playful or radical interests. But, by virtue of the for the exhibition at , the selected hard-copy notes allow for Markéta’s utopian proposal to enter the space for ideas that is invited by the gallery. Being an embodied part of the wider project, of course, Markéta’s Notes can go back into its originating archive and have full circularity (but also become neutralised by this home position). They will also go on to others, including the archive at Camera Austria, and the Living Archive library at the Arsenal Institute for Film and Video Art in Berlin, which Markéta mentions visiting in the folder statement. As a project with an exterior (publishing through archive) and an interior (oral history and a private process of writing and filmmaking), this demonstrates how an art practice can posit different branches of research nested across and permeating one another, scratching out a kind of algorithm in which correspondences emerge, without obligation to synthesis but an attention to the directions taken through emergence, schemata and subjective process.

Reference list

Publications

Holly Antrum, Markéta’s Notes, edition of 400 (Graz, Austria: Camera Austria, 2022).

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London, England: Verso, 2019).

Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1935) in Walter Benjamin, Ed. Hannah Arendt, Illuminations (New York: Schocken Books, 1969).

David Burrows & Simon O’Sullivan, Fictioning: the myth-functions of contemporary art and philosophy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

Ed. Stefanie Schulte Strathaus, Living Archive – Archival Work as a Contemporary Artistic and Curatorial Practice (Berlin: Arsenal Institut für Film und Videokunst e.V., 2013).

Films

Oedipus Rex, directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini (1967; Italy: Euro International Films). Available to view for free (Italian language only) on YouTube.

A Taste of Honey, directed by Tony Richards (1961; England: Bryanston Films). Available to view for free on BFI Player and in BFI Mediatheque, London Southbank.

Exhibition

‘Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen: Intersections in Theory, Film and Art’, curated by Oliver Fuke and Nicolas Helm-Grovas, Camera Austria, Graz, 11 June–14 August 2022.