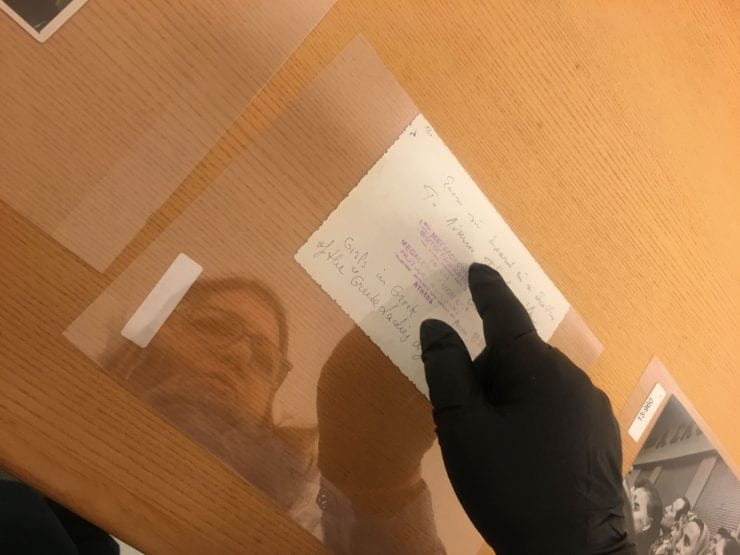

Petroula Asimakis reading handwritten Greek text on the back of a photograph from the Black Star Collection at Ryerson University. Photo by Magdalyn Asimakis.

This is the penultimate guest submission, this time exploring the positionality of the researcher in the archive. Magdalyn Asimakis encounters the presence of Greek women in the photographs of the Black Star Collection at Ryerson University.

Two years ago, I began looking at a series of photographs in the Black Star Collection at Ryerson University in Toronto, Canada. Searching simply the word “Greece” in the database, 1202 results came up, most of which were not photographed. I only made one visit to view the collection before the pandemic, and I brought my mother, Petroula, with me. We were both interested in the surprising fact that many of the photographs were of rural settings, and often of agrarian peasant women, much like the ones we are descended from.

It is perhaps true that the selection we were shown (we did not view all 1202 works before the pandemic) gave the impression that there is a greater representation of Greek women in this collection. However, this did not concern us. We were instead interested in the question of why they were there in the first place, and for what reason the photographs were taken.

Because there is currently no accompanying research to these photographs, we were presented only with the evidence of something through images. Their existence, to us, seemed highly unusual, as in our experience there has been little to no Western interest in the rural mainland Greece, nor the woman’s role in that context. This is partially due to the regional nature of Greece and an almost exclusive Western interest in Athenian antiquity. That is to say, we had never seen evidence of our past outside of private family documents, and we wondered why these photographs were taken. Were they a voyeuristic project? Anthropological documentation? We hoped it was a political gesture. I suspect it was something in between.

Outside of our speculation, my material experience with my mother and this part of the Black Star collection became a critical document in itself. The photographs in the Black Star Collection are a material archive that bridged a dialogue between my mother and I. At the same time, because of her fluency in Greek and experience living in a small mountain village in the south Peloponnese, my mother was able to provide a connective tissue between these photographs that is not present in the institutional archive. This visit became an ephemeral document that revealed the cross-generational feminist potentials of encounters with archives. This seemed to me to be an embodied indexing away from the institution and back into (and an awakening of) matriarchal knowledge.

Magdalyn Asimakis is a curator and writer. Her practice explores embodied experience in relation to Western display practices and methods of knowing, taking into account familial knowledge, folklore, spirituality, and generational trauma. She has organized exhibitions and programs in Toronto and New York, and co-founded the roving project space and collective ma ma in 2018. She is currently completing a curatorial residency with ma ma and Mercer Union Center for Contemporary Art in Toronto, and is a PhD candidate at Queen’s University where she is studying the display of ‘global’ modernisms in museums.

Published by