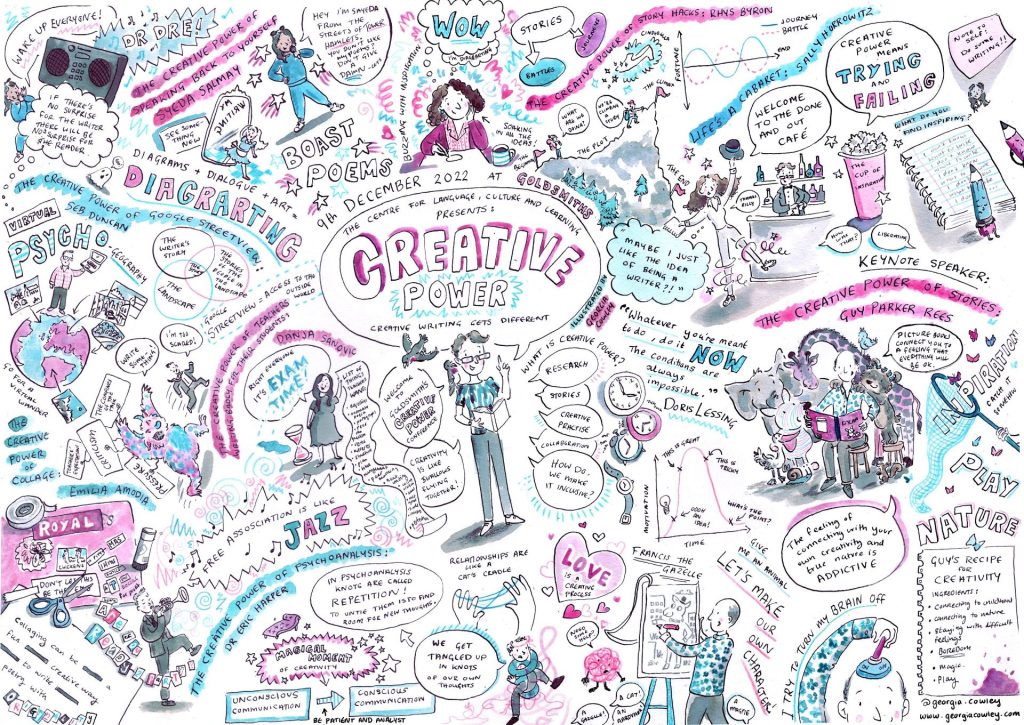

Chronotopic Identity and Translanguaging

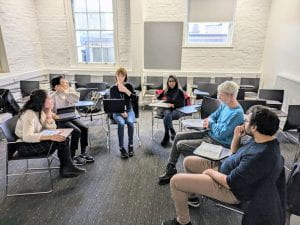

The Multilingualism Research Group meets once or twice a term to discuss topics related to multilingualism. Normally, the discussion is taken from some published research that we read and reflect on. This time we selected two different but related topics, chronotopic identity and translanguaging. Here are some reflections from students that participated in the discussions.

“Since beginning my studies on the MA MLE programme, I have engaged in reading, writing, and debate on truly exciting topics, including translanguaging and chronotopic identities, with the Multilingualism Research Group. The decolonial and post-structural turn in applied linguistics is something that resonates with me on a very personal level because of the struggles I’ve always experienced when it comes to talking about my identities and my languages. Even now, answering common questions such as, “What is your mother tongue?” and “Where are you from?” forces me to trim and simplify so much of my lived experience and material reality for my answers to be comprehensible to others. Blommaert and De Fina draw on the Bakhtinian notion of the chronotope to develop an approach to analysing and articulating identities that takes into consideration the complex interactions between meaning-making practices, specific timespace configurations, wider sociocultural contexts, and personal agency. I am inspired by their assertion that viewing “identities as chronotopic offers invaluable insights into the complexities of identity issues in superdiverse social environments” and look forward to applying this to my upcoming papers on the indexicality of translingual practices in indie music from Hong Kong and the role of social media in literacy learning and maintenance of cultural connections for young, diasporic Hong Kongers.” Melitta von Pflug, MA MLE.

“The idea of chronotopic identities was completely new to me, but I really enjoyed because it was something very much applicable to my own identity construction in my life stages. We show our identities by different ways of using languages such as young people’s language, dialects, and the way we speak among particular groups. Through the reading, it reminded me of my own school days wearing school uniform, building a sense of camaraderie with my peers as ‘schoolgirls’. I no longer have an identity as a young student, and I don’t speak the same way I did then. Perhaps in the future, when we get together with old classmates for the first time in decades, we will start speaking our common language as we used to do. However, it will be a retrospective and nostalgic experience as we have gone through different stages of life and developed complex identities. In the discussion with MA and PhD students, it was very interesting to share ideas about our common or personal perceptions of strategic language use and identities with all of us coming from different backgrounds.” Sumire Kishida, MA MLE.

“In the Multilingualism Research Group discussion, I enjoyed exploring identity and language through chronotopic identity and translanguaging. It was a brand-new approach for me to study identity and language from the chronotopical perspective, that is, the configuration of time and space. I had thought about conventional research analysed from the standpoint of teacher and student, but I am glad that this discussion has given me a new idea of analysing from time and space. It was also exciting to participate in the discussion with people from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. In particular, I enjoyed learning about the translingual practices from the stories of students who come from multilingual and multicultural backgrounds. I loved the opportunity to hear the real voices of multilingual speakers and their language practices, which is unique to the Multilingualism Research Group. I was able to have a very meaningful learning opportunity.” Hibiki Jin, MA MLE.

Blog by Students on MA Multilingualism, Linguistics and Education https://www.gold.ac.uk/pg/ma-multilingualism-linguistics-education/

Find out more or join the Multilingualism Research Group: https://www.gold.ac.uk/clcl/multilingualism/

Find details of upcoming seminars, events and meetings: https://www.gold.ac.uk/clcl/events/