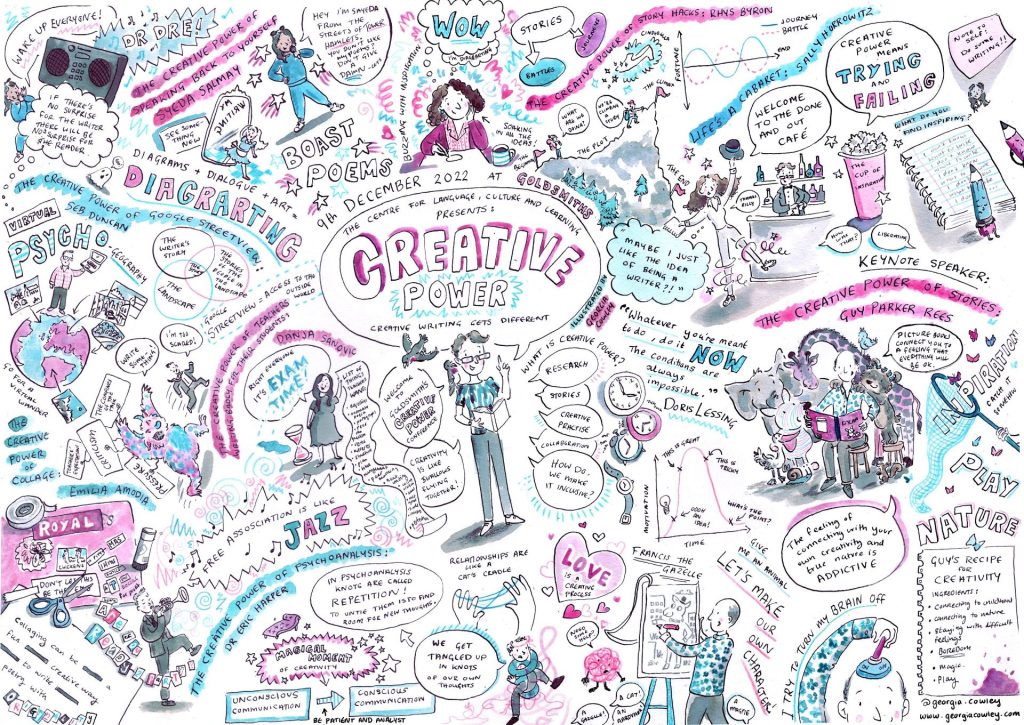

INSPIRE CONFERENCE 2021

Helen Moore delivered an important online workshop as part of the Centre for Language, Culture and Learning’s Inspire conference, which was organised by Dr Francis Gilbert (Head of MA Creative Writing and Education) and Dr Vicky Macleroy (Head of MA Children’s Literature). Here you can read their summation and reflection of her important work.

Wild Writing: co-creative practices & inspirations

It’s a truism that teaching and learning go hand-in-hand. And yet participating in the conference and contributing my insights to an audience of writers and teachers was far richer than I’d anticipated, particularly given its virtual nature. And although I’d always prefer an onsite setting to explore ‘wild writing’, I was delighted to sense that my attempts to convey it online were successful, both in describing it and through a short workshop, with participants sharing what I sensed to be deeply felt experience of wildish places.

But to start at the beginning, what is ‘wild writing’ and how is it ‘co-creative’?

Acknowledging that there are doubtless many definitions, I understand ‘wild writing’ as part of my own ecopoetic practice, stemming primarily from a desire to respond to the social and ecological crises that we collectively face. I believe wild writing encourages an ‘untaming’ of its practitioners, and builds resilience and wellbeing, allowing us to get in touch with our ‘humanimal’ nature and offering us the opportunity to progress the development of the ‘deep ecological self’ advocated by the ecophilospher Arne Naess.

At this point I shared some examples of my own ‘wild writing’, and I’ll include a poem here – ‘Green Drift’, from my debut ecopoetry collection, Hedge Fund, And Other Living Margins, (Shearsman Books, 2012).

Green Drift (by Helen Moore)

“There is no force in the world but love.” – Rilke

Crawling into bed like a peasant,

with mud-grained feet, soil under the nails

of my toes – but too tired to care –

the heaviness of the day’s exertions draws

my body downward – each muscle and bone

finding its bliss – and I close my eyes

on a green panorama, shades of every

nuance, the contours of leaves in high

definition. A film encoded on the visual cortex,

I observe again those lanceolate shapes, the forage silk

which slipped between our fingers and thumbs

(still redolent with that Ramson scent),

the mounding herbage that we plucked,

backs bent as in a Van Gogh study.

Behind my eyelids, vernal waves rise and fall,

hymn of this community to which my senses flock –

ancient rite of magnetic birds, Dionysus riding me,

greens rushing on the inside of my eyelids,

mosaics of foliage, fingers ablaze with Nettle stings,

soles still alive to the narrow woodland path,

its vertebrae of roots, pad of compressed earth.

High on Spring, I’m a biophile

and incurable; nor would I care for any cure –

would only be a node in Great Mother’s body

where, drifting into the canopy of sleep, I see foliar veins

close-up – illumined as if by angels –

feel the breathing of stomata. Then, like a drunken Bee,

I surrender to this divine inebriation.

So how does wild writing happen?

Given that it’s a practice emerging from the wilder aspects of our consciousness, there is a strong need to carve out space in our busy schedules/timetables to get away from the digital world to nourish our creativity and deepen our connection with the other-than-human natural world. But we don’t need to seek out places that might typically be defined as ‘wild’. The wild is everywhere, even in our local park/garden/school playing fields.

It’s also about holding an intention, what does life want to show me today? In approaching it this way, we can experience magical encounters that lift our spirits/bring joy/inspire. It’s important to see the time we give it as ‘sacred’; time for nurturing soul and the ensouled world, and ideally we cross a threshold (which might be a garden or park gate, a path to a beach or forest) in order to mark the transition into it. Whilst in this space, we avoid conversations with other humans and open ourselves to the other-than-human world.

We begin by walking, slowing our pace, letting our mental chatter subside in order to open ourselves. We let our bodies soften, our senses receive information such as the breeze on our skin, scents in the air, taste, sounds near and far, and visual aspects such as colours, shapes, patterns. At the same time, we watch what is at the edge of our consciousness, breathing it in and out, honouring any uncomfortable feelings, breathing them in and out. We avoid getting attached to any of those thoughts, or letting ourselves build them into narratives, and instead keep returning our attention to the present moment.

We also practise the Five Ways of Knowing, which Bill Plotkin advocates. These are sensing (with all five senses), feeling, intuiting, imagining and thinking. Practising and valuing these additional ways of knowing helps to balance out the dominant rational mind and allows us to become more receptive to the multiple wild voices and natural sign languages that are usually so ignored in our culture – in fact, the American ecopsychologist, Theodore Roszak, talks about us having become deaf and mute towards the other-than-human world.

We also connect with the elements, the weather, darkness/light, rhythms of growth, abundance and decay, and notice what these may mirror within us. Observing dead wood riddled with insect holes and fungus, we may see what needs to fall from our own lives, what needs to be composted, as we embrace a deeper understanding of impermanence.

Through these acts of paying deep attention, and then finding language, imagery and form to reflect our experiences, we are engaging in wild writing. However, often that process of finding language is tentative, provisional. Our experiences may be difficult to communicate, and so we simply ‘splurge’, forgetting grammar, spelling, punctuation. Sometimes the seed of a poem or story is found later in just a few words of that splurge, a phrase that has a certain ‘energy’ that we want to explore further.

Wild writing fundamentally requires us to practise non-judgement – at least in the initial phase, when we allow everything in. Later we can practise the discernment of the editorial eye, but for now we are open to including all of our experience. Which connects with the co-creative aspect of this methodology.

What is co-creation?

In our culture we’re conditioned to think of the act of creation as happening almost in a vacuum. We’ve come to think of the creative ‘genius’ working in isolation. Often it’s a white, male figure, possibly inspired by a female muse. However, everything happens as a co-creation in Nature. A tree does not grow on its own, but responds to light, soil, water, weather, insects. It interacts with other trees through mycorrhizal relationships. Trees are also home to birds, creatures, insects, all of whom may have a symbiotic relationship with the tree. A bird might find its home in the tree’s branches, eat its berries, benefitting from this food source, and then pooping out the seeds, thereby disseminating them.

This shows that co-creation is at the heart of all experience. All beings are infinitely connected through the web of life, the ecosystems and communities we inhabit. Our co-creation as humans is with other writers and teachers who inspire us, and with the other-than-human as an interspecies experience. It may also involve consciously working with the Universe, the Divine, Spirit, Oneness, however we may call it.

This co-creation can come about through inspiration, and of course the word ‘inspire’ was key in the context of the conference. ‘Inspire’ connects us with the breath, the air we share with all beings. It is the insights, ideas, sudden intuitions which we ‘breathe in’. And as educators then ‘breathe into’ others when we inspire them.

At this point I invited people to prepare for the wild writing workshop section of my contribution to the conference, with an attunement to our wilder selves through the body and breath. I’m sharing my notes here in case they may be useful for others to adapt for their own purposes:

FOCUS ON BREATH

o Getting comfortable, close eyes, feet on floor, align spine etc

o Noticing breath’s journey in & out of body

o Breath can be shallow, deep, irregular

o What does it mean to be at home with our breathing/to inhabit our breath?

o Air penetrates deep into our lungs through this act of respiration, reaching the minute balloon-shaped air sacs that could be leaves at the end of the respiratory tree’s branches.

o Their function is to exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide molecules to and from the bloodstream.

o Of all the elements we’re able to survive the least amount of time without it

o We share the air, as we do water, with all human and other-than-human beings. Here we are inescapably experiencing this miraculous existence together inside a delicate pocket – Earth’s atmosphere, a phenomenon I explore in this section of my poem:

READ EXTRACT: ‘From the Pocket’s Circumference’ (ECOZOA, Permanent Publications, 2015)

“… here’s the rub – don’t we all live together in the same pocket? From outer space we see the pale cloud, and here and there the holes. If Earth were a fist balled up and thrust in a pocket, the atmosphere would be as thin as that cotton fabric. Our lungs know this. Drawing 20,000 breaths per day, these twin inflatable pockets point up towards the element on which they depend.”

VISUALISATION

Walking into a forest/woodland you know. Air filled with sounds of birds. The Spring sunshine is gently warming the air and your face. Sap is rising. Season when our ancestors would have celebrated the Earth’s awakening. Birth. Regeneration. As you walk, perhaps you’re starting to breathe in the scents of blossom, new leaves, Wild Garlic?

Talk about Japanese Forest Bathing – Shin-rin-yoku. As we walk in woodland, we’re breathing more oxygen-rich air. Also we’re benefitting from the forest’s natural aromatherapy. Inhaling the aromatic compounds released by trees and plants, called phytoncides. These have natural antibacterial and antifungal properties, and studies show that they support the white blood cells in our immune systems. Take time to be in this space etc.

Finally, I invited people to plunge into some splurging, and gave them five minutes. After that, I asked them to look at their writing and circle any parts that had interest/energy, which might serve for further development.

In the final minutes of the session, people typed into the chat some wonderfully rich snippets, read out some sections of their writings and asked questions. I’m hugely grateful for everyone’s engagement, and I’m open to ongoing dialogue with anyone who may want to know more.

BIO

Helen Moore is a British ecopoet, socially engaged artist, writer and Nature educator. She has published three ecopoetry collections, Hedge Fund, And Other Living Margins (Shearsman Books, 2012), ECOZOA (Permanent Publications, 2015), acclaimed by John Kinsella as ‘a milestone in the journey of ecopoetics’, and The Mother Country (Awen Publications, 2019) exploring aspects of British colonial history. Helen offers an online mentoring programme, Wild Ways to Writing, and works with students internationally. In 2020 her work was nominated for the Forward and Pushcart Prizes and received grants from the Royal Literary Fund and Arts Council England. She’s currently collaborating with Cape Farewell in Dorset on RiverRun, a project working with scientists and farmers in Dorset to examine pollution in Poole Bay and its river-systems. www.helenmoorepoet.com

Blog by Helen Moore