It is Monday morning, June 27th 2022, at Deptford Green school and the library is full of the great and the good, all of whom are keen to improve the parks in Lewisham: a freshly elected local councillor, Stephen Hayes; park managers, representatives from community organisations and a park user group, the Lewisham education lead for taking action against the climate emergency, as well as various academics from Goldsmiths university.

A number of Year 7-10 pupils (aged 11-14 years old) are wonderfully calm as they address this intimidating audience about their local park, Fordham Park.

Assisted by the amazing poet Laila Sumpton (a specialist in youth advocacy), Masters and Undergraduate students at Goldsmiths University, which has funded this pre-pilot for a larger project, these young people have been researching Fordham Park for months, using some cutting edge, creative research strategies. They’ve toured the park extensively, taken photographs and written poems, produced art, and collages about it.

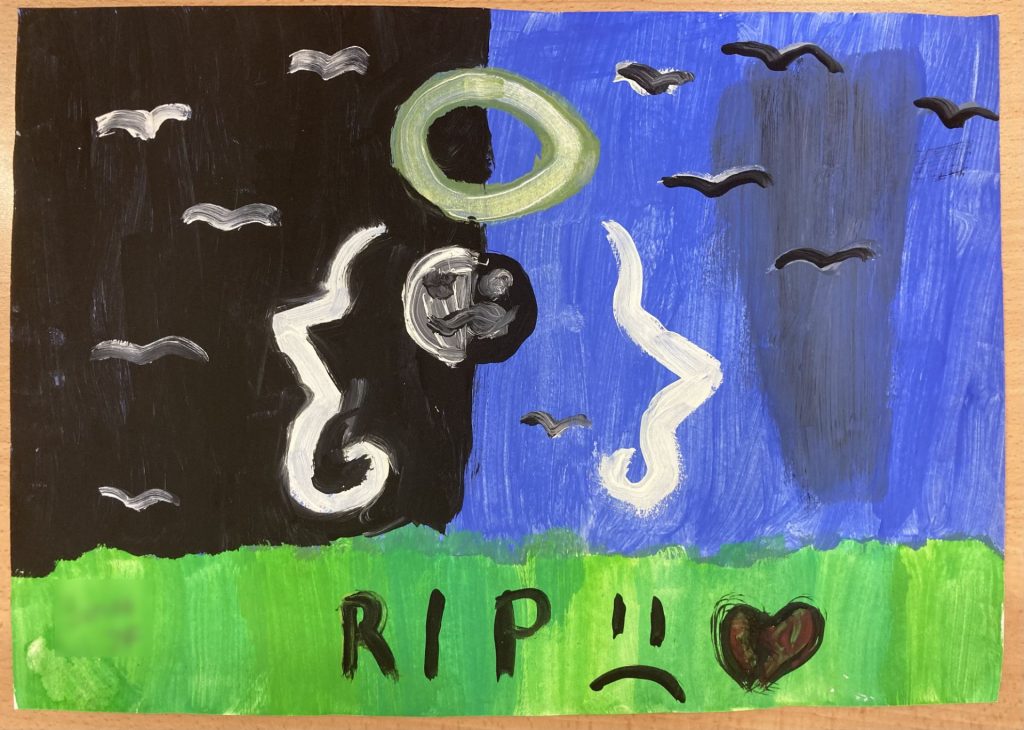

A painting by a Deptford Green pupil about a young man who was killed in the park recently

A 360 picture of litter picking.

An animal eye’s view of litter in the park.

A 360 photograph of the park and the park researchers.

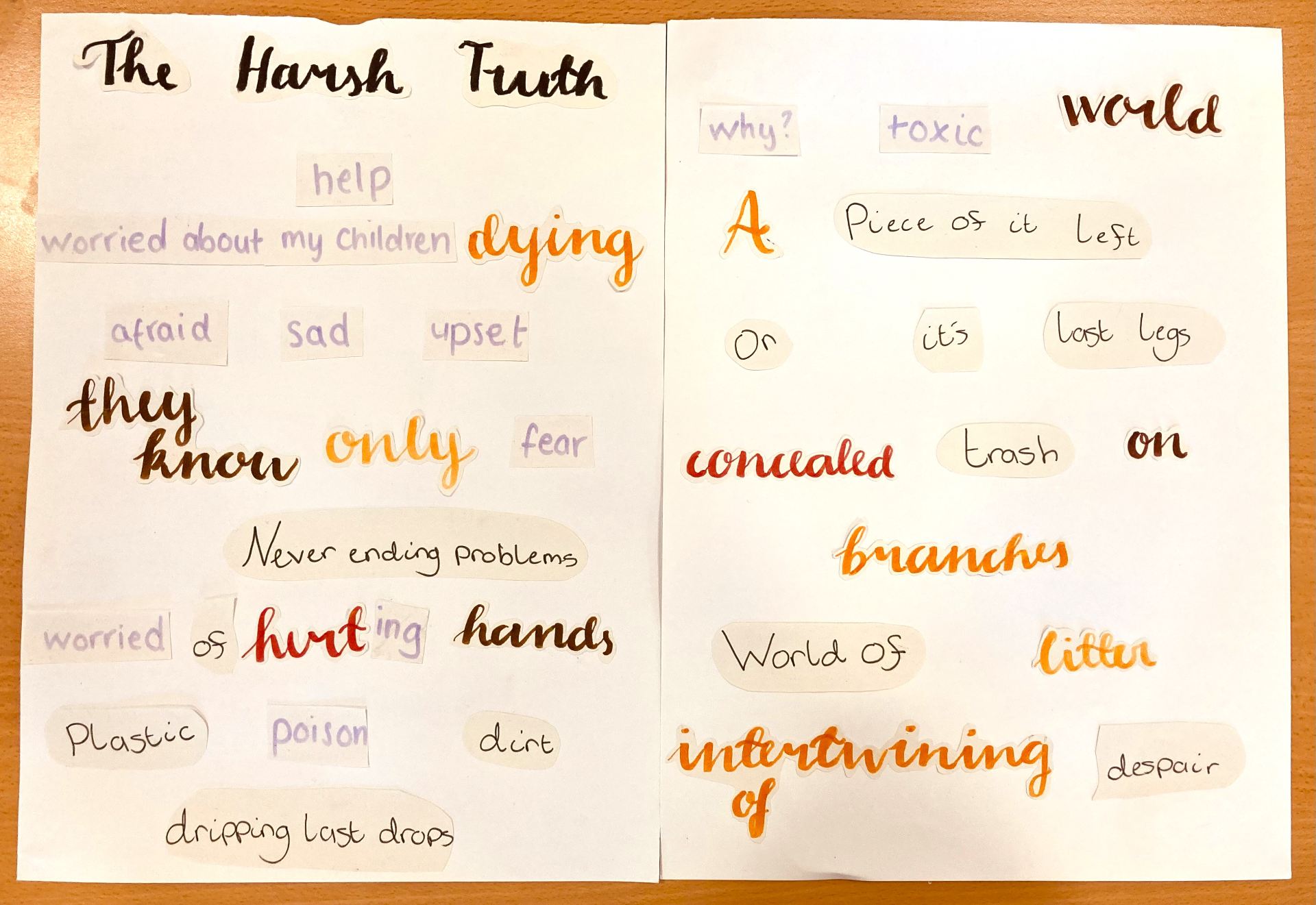

A cut-up poem about the park.

They’ve surveyed teachers and pupils about their attitudes towards the park, and they produced this film about it:

Now, on this Monday morning they are sharing their findings, and advocating for change. They have drawn up a series of short term and long term goals that they would like the relevant people to act upon:

A poster of all the goals the students devised.

Their talk illustrates the work they’ve done, and then an intensive question and answer session happens, with the young pupils from Deptford Green really drilling down into the nitty gritty of how the park might be changed for the better.

At the end of the session, relevant members of the audience come up with pledges to change things for the better. These include:

- The parks’ management promising to help facilitate improved litter picking in the park, and the establishment of a community garden.

- The local councillor promised to examine how the council can help young people feel safer in the park; he will set up meetings with the relevant police and safer neighbourhood teams; he will also join the young people in litter picking around the park.

- The park user group will involve pupils in the setting up of a water fountain and a bicycle repair station, which have been approved by the council.

- The Lewisham community leads will help the school link up with local residents, a local community garden initiative, and other relevant local groups. They will connect them with Keep Britain Tidy, a powerful lobbying group, and will use some of the images they have produced in a poster campaign.

- The Climate Emergency education leader will help the young people to present their findings to the Climate Emergency school activists group in Spring 2023 and will connect them with the waste recycling team and the Young Mayors’ team.

- The charity Street Trees for Living committed to planting new trees in the park.

This is just the beginning. Deptford Green school are keen to become an eco-school and will be expanding the Parklife project next academic year in collaboration with Goldsmiths. Research shows that parks can significantly help young people’s health ( Day & Wager 2010: Steletenrich 2015: Neal et al 2015: Rigolon 2017). It’s clear that getting these young people involved in researching their local park and changing it for the better could lead to significant impacts for them and other young people, which might include:

- Improving the vegetation in the park which can lead to improved air quality: the community garden and other possible rewilding projects could do this.

- Offering a ‘reprieve from noise’ and new ‘blue spaces’ such as bodies of water

- Cognitive benefits which come from being regularly in green spaces

- Improving vision which comes from spending more time outdoors

- Improved socialization which comes from socializing in the park

- Improved physical activity

(Summary of Steletenrich 2015: 256)

References

Day, R., & Wager, F. (2010). Parks, streets and “just empty space”: The local environmental experiences of children and young people in a Scottish study. Local Environment, 15(6), 509-523.

Neal, S., Bennett, K., Jones, H., Cochrane, A., & Mohan, G. (2015). Multiculture and Public Parks: Researching Super-diversity and Attachment in Public Green Space. Population Space and Place, 21(5), 463-475.

Rigolon, A. (2017). Parks and young people: An environmental justice study of park proximity, acreage, and quality in Denver, Colorado. Landscape and Urban Planning, 165, 73-83.

Seltenrich, N. (2015). Just What the Doctor Ordered: Using Parks to Improve Children’s Health. Environmental Health Perspectives, 123(10), A254-A259.