Laura Thomas is a radio producer at BBC Radio Four and writes on film for Lancet Psychiatry magazine. She’s currently working on a novel imagining the early (and sometimes dubious) adventures of Richard Hannay, hero of John Buchan’s action thriller The 39 Steps; and on a series of short stories about being a teenage girl in the 1990s.

ljt1977 (@gmail.com)

*

Preface: 1938, Oxfordshire

“Humility before the facts”

I once heard a story at my club about a man who got lucky in Egypt. Out walking near the ancient tombs, a native offered him one of their amulets for a few coins. He brought the thing home to Northamptonshire (or perhaps Surrey) and put it in his library. Then his troubles began. Perhaps the shadows of the English winter didn’t agree with him after his travels, for he never slept an easy night in his bed again. Apparently the chap told anyone who would listen – and they became rare – that he was cursed. The next thing his friends knew, he’d gone off hunting in Africa, where he was gored to death by an inexpertly-shot elephant.

I was raised to believe that you can tell a man by how he meets your eye, how he shakes your hand. Women have always given me more trouble, but men: men I’ve lived among, and understood. Hannay my friend, I’ve said to myself, you can always tell a man by his bearing, his gait. It’s all there if only you’ll look. But lately when I say this to my son, he looks at me queerly. Perhaps it’s advice he’s outgrown, like he’s outgrown the adventures of my past. His mother keeps her counsel. These days I find myself often and often alone, smoking in the snug, thinking of our friend and his bit of luck in Egypt. Once it would have seemed weak stuff. Once I would have said: some chaps just aren’t built for the colonies and there it is. I’d have told you that I knew his type and that it’s a type given to childish fancy. But lately I’ve begun to wonder. Paddock, still my manservant after all these years, and never shy with an opinion, cheerfully admits he thinks us cursed.

I have not written about my Matabele experience until now. We’d heard from the big men, men like Selous and Ironside, and in the years since, every scout, missionary and two-bit hunter has had their say in print. To be frank, the Matabele war seemed like a petty local skirmish in the light of what followed. I’d made my pile, not one of the big ones, but good enough for me. Who wanted to read about a fuss over a savage king and a few burnt huts when Europe stood on the brink of disaster? Yet these days, as I sit in my snug looking out at the distant Cherwell, I could fancy it’s no mist that I see, but instead the smoke from those same burning huts, drifting up from another valley, one far away in time and place, and enveloping my old Oxfordshire manor house. Perhaps the shadows of the English winter no longer agree with me.

I’m Major Richard Hannay of the Lennox Highlanders, hero of the Thirty-Nine Steps, as the papers never fail to mention. You can tell nothing about me by shaking my hand.

Chapter One: March 1896, Rhodesia

“Jolly little wars”

My father brought me to Africa from Scotland age six. I soon forgot the old country. We lived in what would shortly become Rhodesia, in the lee of the Mulungwane Hills, high up on a bend above the Ncema river. It was a simple place made of wire-weave walls sent by boat from England, scarcely more than two rooms, but it was sturdy – the ravening ants had no taste for steel mesh – and a veranda encircled the little house on three sides. Our cattle grazed the rich grassland as far as the Eureka goldmine. My mother having died when I was small, and my father’s days being much taken with the cattle and the business of running the farm, my time was my own. I was never much of a boy for books, but I knew every tree and rock, every glade to hide in, every pool where fish waited. Starting from the farmstead in the cool of the morning, the dogs at my heels, I fished and climbed trees to find birds’ eggs. Rhodesia was home. It was mine. I believed my only enemy to be the wicked old crocodile that waited in the sluggish pool at the head of the falls downriver from the farm. Things stayed that way until I was nineteen years old, when the Matabele rebellion broke out.

Like most farmers we allowed natives to camp on our land in return for help on the farm. I liked to think that because we had always treated them kindly, and because they had benefitted by us, they would not wish us harm. In those days it was understood that if a Kafir was owed money by an Englishman or Scotsman (a year’s wages, say) he would take a letter, without a murmur, to another English or Scotsman living hundreds of miles away, if he were told that on delivering the letter payment would be settled. Meanwhile, there were perhaps just a handful of Boer hunters in the interior the Kafirs would trust in such a way. Over towards Zumbo, your Portuguese could not make a native stir hand or foot without payment in advance. These rules and understandings were self-evident; they governed our world.

Then, on 23rd March of ninety-six, came the murder of the native policeman at Umgorshlwini. Later it would be understood as the first overt act of rebellion on the part of the Matabele. I had been away from the farm since the previous Sunday morning, hunting antelope in the hills, and so was unsuspicious of danger when I returned on the 24th. I reached home about mid-day, and my father told me that during the morning some men – all of whom I knew well – had come over from the nearby village. Several of them were in charge of cattle belonging to us. They all wished to borrow axes, my father said, for the purpose of strengthening a kraal. We were accustomed to assist the natives in any small matter of this kind, so my father let them have those axes that could be spared, and allowed them to sharpen them on the grindstone. The business of the axes seemed small and ordinary and so we talked on comfortably enough, my father and I, about our old headman, Bekhizwe, and the son who would succeed him. At that time I was beginning to be more closely involved in the farm’s affairs and our chief concern was rinderpest – only rinderpest! – travelling west and south over the continent from Somaliland; it brought death to cattle and ruin to cattle farmers. It had not reached us, but we knew it was stalking closer with every new moon.

“It’ll burn itself out,” my father assured me that day.

But his face, as he walked past me to the end of the veranda, was tense. He stood with his back to me, looking out at the hills where our cattle grazed. I felt too bone tired from my long ride to engage in speculation of this kind so I said nothing. Besides, I had no wish to name our enemy, for I found I had an obscure sense that naming calls, so I rose and commenced looking about the yard for someone to rub down my horse. It was then that I noticed the boy. He must have been approaching the house for some time and yet we had not seen him. Small and slight, he was no more than twelve. He stood hesitantly, twenty yards off, holding an axe in his right hand. I walked out to meet him and immediately saw by the dust on his feet and clothes that he had come a long way on foot. I recognised him as a nephew of Bekhizwe, one of the crowd of boys who lent a hand each summer with the cattle on the hillsides.

I called out to him. Receiving no reply, I held up my hands to show him that I meant no harm, and searched my memory for his name. It would not come. Still the boy said nothing, only swallowed and took a step back. He was sweating. I tried again.

“Can I help you? Are you looking for me?”

He nodded, looking past me as he did so and over my shoulder, to where my father stood on the veranda. I grew impatient.

“What do you want?”

I stepped towards him. He turned tail and ran.

Whether the boy came to kill us or to warn us that afternoon will always remain a mystery to me. The news from Umgorshwini, with its details of smashed heads and bloody footprints, didn’t reach us until much later; so late, in fact, it could serve only as confirmation and not as warning. Besides, the events of those days made me feel it impossible for a European to understand the workings of a native’s mind. I felt that although I had been raised to see the Kafirs on our farm as friends, I knew nothing about them, and was incompetent to offer an opinion as to the line of conduct they would be likely to adopt under any given circumstances. Servants and farmhands rose up and killed families to whom they had been loyal for years. Later they explained that they bore their victims no personal ill will. They simply stood in their way. I know now that in all likelihood our axes were used on the luckless inhabitants of the mining camp situated not five miles from our farm later that evening. From there the rebellion grew and spread until by the night of the 30th scarcely a white man, woman or child was left alive in the outlying districts of Matabeleland.

Before I continue, let me say I do not see the need to defend the desire I felt then, aged nineteen, for vengeance. Although the murder of Europeans by savages may commend itself to certain arm-chair philosophers in England, who can see no good in a colonist, nor any harm in a savage, the colonists themselves cannot be expected to look upon such matters from the same point of view. There had always been incidents of one kind or another. Settler kills savage; savage kills settler as the battle for supremacy, what Mr Darwin calls the survival of the fittest, ground on. To those that called it ugly I would say, well, the British Empire cannot be run from Exeter Hall. I would also tell them it was a battle we would win.

After the boy disappeared, my father and I headed on foot to the Kaffir huts out on the edge of the farm. Where once we would have found children playing, women lighting fires or cooking or sweeping the yard, we found emptiness and silence. Suspecting something was ill, we saddled up and rode out to the Cunningham farm, some three miles off, hoping to fit the outline of our suspicions into the suspicions of others; to begin to understand what we were dealing with. A mile out from the Cunningham place we saw smoke rising and rode faster. As we approached, it was clear that a once fierce fire had died down, leaving the farmstead charred and smoking. I called out, hoping that any survivors hearing my voice would creep from their hiding places.

“Cunningham! Cunningham?”

I made to dismount, but my father gripped my shoulder.

“Dick, stop.”

He gestured to the side of what had been the farmhouse, where something pale and bright fluttered on the ground. I walked my horse towards it, but it shied, refusing to go further, and I was obliged to lead it. The little girl was perhaps five or six. She was shoeless, the skin on her splayed arms and legs a healthy gold, and she wore a summer dress of pale green muslin. A ball lay in the grass a few feet from her, and bonnet, perhaps tossed aside in play. Blood and brain matter covered her face and stained her pale hair. Her skull had been smashed. The instrument of her death, a kind of native club we called a knobkerrie, lay on the ground, broken, beside her. Next to her in the grass was her brother James. He was alive when we knelt beside him but could not speak, and expired soon after. Mr and Mrs Cunningham lay a little further off, their bodies mutilated in ways I will not set down here but which – should you care to – you may read about in the newspapers of the time. Grass had been piled on their corpses and set alight. Cunningham’s Martini Henry lay beside him. The barrel was fully loaded. The poor devil hadn’t fired a single round.

I say again that I do not know why and how we were spared. All my life a curious kind of luck – if a shivering survivor, eyes wide and hair stiff with horror, can be said to be lucky – has followed me. It was with me that night: we heard that families of three and four had died together, fighting hundreds of savages to the last cartridge, huddled behind a wagon or cart. It was with me as the new century came and we fought a new war, this time against the Boers. It was with me still, somehow, at Loos, if luck is to survive being gassed by your own side.

Returning to our farm from the Cunningham place, we found that our cattle had been driven off. My father regarded our broken fences and empty pastures with a composure I found I admired even in that terrible moment, then he turned to me.

“Dick,” he said, “we have been wrong.”

“How, father?”

“Wrong to believe we were living in peace.”

Looking back from the vantage point of more than four decades, I admit it does not seem within the bounds of common sense to have supposed that a nation of ferocious savages would ever have allowed us quietly to take possession of their country without resenting it. Even to have entertained the idea now seems insulting, and yet we had entertained it.

Together with my father and a few survivors from neighbouring farms we made up a patrol of some fifteen men and horses and helped to bring people to safety in Bulawayo, some thirty miles off. My father remained there: experienced men were needed to run the supply lines to the now laagered town and the few hundred souls it sheltered. I continued alone by train to Mafeking, for it was there and at Kimberley that Mr Rhodes’s British South Africa Company recruited its Matabeleland Relief Force.

Chapter Two

I become a soldier

Chancers in slouch hats filled the streets, hotels, and bars (above all, the bars) of Mafeking. Julius Weil, that universal provider, owner of those same hotels and bars and proprietor of stores all along the road to Bulawayo, settled in to profit from the times. Coachloads of refugees arrived from the North. The town was in a ferment of excitement and anxiety, rumour ran in exhausting circles, and every man looked for the opportunity to fire a gun in anger, or make their fortune, but preferably both. We recruits camped near the railway station in regimental order, half a mile from the centre of town.

I recognised many of those camped around me as men used to the game of war; men like my father, with experience in Kaffir wars in Zululand, Swaziland, Basutoland. Many had fought in the trouble in Matabeleland in ninety-three. Some were veterans of Cape Mounted Rifles and the Natal Police or had travelled with the original pioneers in eighty-eight. For myself, I could handle a horse and a rifle, and hoped to honour my father. Yet as I looked around I saw that there was another breed among us that day. Back in the nineties any sportsman who wanted to get rich quick had his eyes on the gold fields of Matabeleland. Cecil Rhodes was often up-country, pushing for the expansion of his beloved railway. He left administrative matters to his right-hand man, Dr Jameson. The doctor, in his turn, surrounded himself with a high-living, wild set of aristocratic young men. Piccadilly Johnnies, my father called them, “aye, hoping to make a million in half-an-hour and then clear off home, lad, you mark my words.” A medical man by training, Jameson had made himself indispensable to Rhodes by cheerfully writing up diamond miners with smallpox as cases of chickenpox or psoriasis. Occasionally a civilian – a woman expecting a child, perhaps, an invalid or two – died from this so-called chickenpox, but Jameson or Rhodes (sometimes Jameson and Rhodes, if the victim had powerful friends) were able to square away the coroner. They had made it their business to understand not only that official’s tastes in opium, native women, and Hartley’s Book of Knots, but to understand how those interests fitted together. It was not wasted knowledge: the mines remained open and the public remained calm.

Lately, Jameson found that poker left him little time for doctoring. And after all, what else was there to spend money on in Rhodesia? Wealth and boredom meant that men would bet high stakes on how many flies would land on a sugarcube. One night, my father told me, Jameson bet his house and his practice at poker and had lost them by midnight, only to win them back as dawn broke. No doubt it was that same high-rolling spirit that led the doctor and his friends to ride into the Transvaal and cause a stir over the border. The British public may have loved him, but we settlers thought him and his followers reckless. It was with dismay that I saw their type in Mafeking. In theory the force required all recruits to prove skills in riding and shooting, but even at nineteen it was clear to me that men devoid of both accomplishments, and indeed devoid of sense, had been recruited. They seemed to regard what we were about as little more than a chance for a change of scenery and life in the open air.

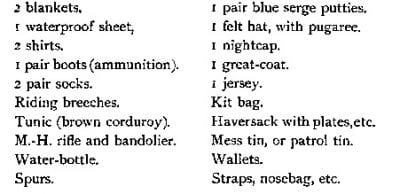

Lastly, our numbers were complemented by a few poor bronchial specimens, the inhabitants of some blackened old-country slum seeking a better life in the colonies. Poor Devils, their empty wallets and uniforms were all they owned. But veldsman or chancer, pauper or Piccadilly Johnny, the Company called us troopers and paid us alike: 7s. 6d. per day, rations included. Within five days a force of some five hundred men and horses had been assembled. We were to be joined in due course by five thousand from Johannesburg, plus five hundred Cape Boys. Each man, on passing the doctor, was supplied with:

M.-H. stood for Martini-Henry, Mark IV, with sword bayonet. The nightcap came in handy on cold evenings. Overall, however, supplies – of Martini-Henrys, of nightcaps, of everything, were limited. Those men arriving later had to be content with what was left, which wasn’t much; as a result, theft in the brand new Matabeleland Relief Force was rife. On the 12th April we were despatched in fourteen glum regiments on the long ride to Macloutsie. From there, my troop was to make for the district of Bulawayo, which – the rumours told us – faced being overrun at any time. I was going home.

Yet it was on the trek to Macloutsie, boy though I was, that I began to feel I had got myself into the wrong game. The following may be taken as a sample of the routine for each twenty-four hours: reveille at 3am or 3.30, depending on the distance to be trekked to the next watering hole; saddle up half an hour later. Trek till nine or ten o’clock, sometimes till noon, without food, dismounting every hour or so to rest the horses. On arriving at the outspan, stables for half an hour, then rations issued and breakfast cooked. Rest until half past three, snatching sleep (flies permitting). Then pack up kit, saddle up and march until late into the night when, off-saddling, the second meal would be cooked. From this it will be seen that no over-indulgence in food or sleep was allowed.

As we rode on, we began to see for ourselves the damage that rinderpest had wrought to the countryside. No cattle had been available at Mafeking to pull our wagons, this much we knew, but once out of the township and on the road to Crocodile Pools and beyond to Gaberone, the reasons for that lack became clear. The corpses of oxen littered the roadsides and the country around in varying states of decomposition, their measled faces horrific to look at, their bodies stinking and bloated. Oxen were better suited than horses to the veldt, and had been a mainstay for transport all over Rhodesia. Now they lay dead in harness, thousands of them, abandoned by their drivers. Our horses bucked and shied at the sight and the stench. For the inexperienced riders among us, this was a severe test, and one which they could not hope to pass. In went the spurs, down went the horse’s head; a disconnection between mount and rider was soon effected. Those of us with the wit to sit deep in our saddles had a hand free to pull our neckerchiefs over our noses; still the high sweet stench clogged our throats. Years later, in the shell craters and trenches and fox holes and hell holes of Flanders, among the corpses of gassed and bayonetted men, where the mud waited to suck the dying down into blissful oblivion if only they would yield and let it, I would remember that smell on the veldt. I did not know then I would be a soldier all my life; that the wars would line up to form a patient queue. Just one more, and then we’ll be at peace. I thought the reek of carrion would pass, but this twentieth century is choked with it. I did not know it would hang over the fields of Flanders, over the Syrian desert, over Bloemfontein and Bethulie, over the empty lands of the Herero and the jungles of the Belgian Congo. Decades have been insufficient to wash it from my nostrils.

When we bivouacked for the night, our cook would make the little oatmeal cakes which, together with tins of bully beef, comprised our ration. One evening I was engaged in shaking a scorpion out of my blanket when I saw a pair of steady blue eyes regarding me from across the fire. Their owner was somewhat shy of six foot, with a gentle face. When he spoke, his voice was sleepy.

“Transvaalicus.”

“Excuse me?”

“I said Transvaalicus. Your friend there.” He gestured to the scorpion, clinging still to the pile of the blanket by one powerful pincer. “Ever seen him sting?”

“Once.” I remembered the disturbed insect, its poison sprayed at a victim from a distance of two feet, the resultant yelp. “A dog back at the farm.”

He nodded and squatted on his haunches, seeming satisfied, and lapsed back into silence. Detaching the scorpion at last, I sent it into the fire with a sharp kick of my boot. Unscathed, the creature rolled neatly through the outer flames and regained its legs before walking away, in no hurry, its shell smoking in the moonlight. Another man might have looked for a rock to crush the crawling thing, but though the blue eyes watched the scorpion carefully, he let it go.

“Like God’s own Maxim gun, that one.”

The blue eyes creased with genuine mirth.

“I’m Pienaar.” He held out his hand. I took it.

“Hannay. Dick Hannay.”

In that moment one of the most vital friendships of my life was born. I’ve lived a solitary kind of existence, often in danger, often relying on myself alone. Peter, too, lived a solitary life, but in times of great crisis we have stood together, and trusted each other’s judgement more than our own.

“Where are you from, Dick Hannay?”

I told him about my father’s farm and he listened shrewdly, eyes half closed.

“And when this is over you’ll go back?”

It was the first time the idea had appeared to me in the form of a question. It was mine to go back to, wasn’t it?

“Of course.”

He regarded me intently for a moment, then smiled. “Alright.”

I learnt that evening that Peter had been a hunter and a prospector, mixed up in many schemes in South Africa and the Portuguese territories, none of them entirely straight. He was of that rare type who can walk amongst corruption and remain as true as an arrow, a mercenary who fights for his own reasons. Yet I knew that I wanted to trust him. As he stretched out for the night, his hat over his face (but no nightcap) I felt I had an ally for the first time in many weeks.

When I awoke in the morning I saw that Peter was already saddling up. In the thin winter light, men gathered their scant possessions and rolled their blankets, cigarettes glowing in the grey light. We spoke little, and throughout the morning kept up the same furious pace that we had maintained over the previous weary days. It was late in the morning when we overtook the abandoned wagon train. The cattle lay where they had fallen, their bloated bodies still inspanned, their limbs tucked under them like sacrificial beasts, or thrown out in attitudes of agony. We were forbidden to approach the wagons on Company orders, but we had been short of supplies when we left Mafeking. This time Powell, our commanding officer, a dramatic chap with a rather theatrical taste in leather riding gauntlets, raised a gloved hand to indicate that we should come to a halt:

“We need blankets; bully beef; ammunition; axes; any spare tack you can find. Four men to a cart. You have fifteen minutes.”

We mastered our revulsion and stepped closer to examine the stranded livelihoods of the traders and merchants where they lay at the roadside. The tarpaulins covering each wagon had been picked at by vultures, but remained for the most part in place. Peter took his hunting knife and slit the ropes that bound the tarp to the top of the wagon. I hauled back its skin, and then climbed inside. Bales of cloth were heaped at the far end. Sacks of flour left just enough standing room for me to see my footprints in the white powder dusting the wagon’s floor. I called down to Peter:

“Nothing here for us.”

I lifted my head and looked down the line of wagons to see two of my fellow troopers, Rose and Willoughby, clamber into the back of the next wagon in the line. Rose, a plump villain with soft hands and eyes like a snake, Rosie to his friends, stooped and used his bayonet to prize open a crate. Willoughby, who for some reason we were all invited to call Monkey Nuts, busied himself alongside. The lid of Rose’s crate gave way and he and Willoughby peered inside, rapidly exchanging a glance they attempted to make casual as Powell approached:

“What have you got?”

“Looks like whiskey, sir.”

As the news rippled down the line, we set about opening further crates in the second wagon and found liquor of all kinds, port, gin, fine wines, champagne, all of it destined for the hotels and dining tables and gambling tables of Bulawayo. Willoughby and Rose began lifting crates from their places. More men gathered around the abandoned wagon. A cheerful holiday atmosphere was detectable where previously there had only been exhaustion. Then we head Powell’s voice:

“Willoughby. Leave them.”

“Sir.”

I reflected that few men were blessed Willoughby’s ability to make the word seem so little like an acknowledgement of rank and so much like an insult. Perhaps Powell felt it too, for he continued, unnecessarily:

“The Company’s policy is to leave wagons untouched unless there is a proven need for the goods commandeered.” This we all knew.

Rose smirked. “I can prove my need for the whiskey, sir.”

Yet Powell’s boyish demeanour had a way of hardening into something darker and angrier when tested, and it did so now:

“Halkett, Wilson” – he pointed to two troopers loitering on the edge of the group with the suede finger of that luxurious glove – “open the third wagon. Then saddle up. Rose, step down or you will be removed and court-martialled for insubordination.”

As Halkett and Wilson began slicing into the skin of wagon number three, Rose and Willoughby climbed down from their vantage point next the whiskey. I watched them as they made to walk back to their mounts, studiedly casual, their manner dangerous.

A voice called out. “Bullets, sir.” This was Halkett.

“Load them up, Halkett. Oh and Pienaar, Hannay.” The glove gestured our way. “Cut any useful tack you can find from the cattle.”

We regarded the corpses. Tack, like other supplies, was running short and so we mended bridles and saddles as we travelled. Here was a good supply of harness leather, providing of course you didn’t object to wiping the pus off first. Choking as we worked, our scarves pulled up over our mouths, we bent no closer than could be avoided to the diseased faces, ripping gore-encrusted buckles from their bindings, loosening girth straps that bound gas-bloated guts, and throwing the spoils into a seething contagious heap for other troopers to douse with dust and wipe clean. Then we discarded our gloves, wasted two canteens of water on rinsing the stench from our faces and hands and mounted up. The patrol rode on.