Christina V Palmou is a poet and an economist. In 2020 she was longlisted for Southbank Outspoken Award for page poetry and in 2017 for the National Poetry competition. She has performed in Spoken word nights in Lisbon and all across the UK.

Twitter: @PalmouChristina

Contact: christina.v.palmou@gmail.com

_____

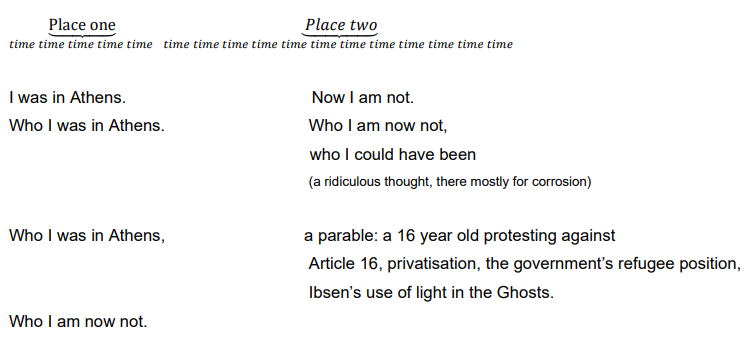

Southern Fictions

ii.

When I am sad, I think about being on the side of the road in December in Athens. It is raining and you hear the tires as if waxed off the road as the cars pass by. Car lights reflect off the puddled potholes and shop windows, and it all has an improvised Christmas feel. I am twelve. I am standing by my mother. She is trying to hail a taxi. Imagine her wearing a dark cape, a pair of boots, brown eyeshadow, golden earrings, thick black-brown hair, a middle-class Athenian woman in the nineties. Something you might find hard to imagine being British, or Nigerian, or a man, being a person from the place that never rains or being a person from a place with no cars, being a person void of the imperative of imagining, and most importantly not being the daughter of a middle class Athenian woman in the nineties. She smells of a sweet, strangely bottled perfume and powder rouge, she loves being with people and family which is where she is hailing the taxi from and to. Her marriage is falling apart but at the time all I know is that I am about to continue snooping around somebody else’s house after a 20-minute interval in the cosy, conifer car-refresher smelling comfort of a yellow car.

This is the memory I dig into, living in a rainy place and wishing I had so many loved ones around that I would need taxis to drive me from one to the other several times over in one evening.

When I am sad, I think about the small bathroom in our first house whose fan, a could-have-been retired helicopter part, used to give a comforting sense of privacy in a tiny flat of four people. The white tiles, the dried warm towels on the radiator after the shower. My father’s rhythmic, heel-first steps along the corridor. The black bookcase floor to ceiling heavy with Companions to the English language, Garcia Márquez and The Alchemist. I had peed all over The Alchemist as a baby my mother says. There is a long horizontal crack above the entrance door, a scar from the earthquake of ‘96 when, faithful to government advice, we had run to the street, “Papapodoulou” cookies under arm, the biscuit figurehead of a generation, and waited for hours either for the aftershake or for the cracks to seep deep into the decades-old concrete block and bring it to its knees. None of this happened and the evening is remembered for learning the neighbours are also having problems with their bathroom pipes, and agreeing we should bring it up in the tenants meeting, that Christos and Andreas are the names of the upstairs couple’s children, one of which despite being no older than seven reminded me most of a retired Fred from the Flintstones, until finally in the late hours, chewed in neighbourly warmth, we were absorbed, shaken, back into the building. The building still stands cracked 30 years on between a car repair shop and a pink eight-bedroom house fenced by cypress trees. A sort of dolls house, as if placed there as an ornament in an otherwise multi-story, multifamily neighbourhood.

When I am sad, I wish I were back at that flat where there was always a neighbour’s apartment to run to, looking for respite from childhood boredom, always the doll’s house to look at when short of a story, when there was normalcy in living among benign earthquake cracks, unthreatened and guiltless, a certain inevitability to it, a nonchalance inherent in closing the door a little too fiercely on the way out or in just lying there, melted inside the worn-out cushions of the living-room couch, reading, looking at the possible collapse, ageing, suspended over your head. From time to time comes uninvited the desire to return to that flat, where there was always a way to rub off red wine or ketchup off clothes, where carelessness didn’t have to stain forever.

Nothing has happened. Nobody has died, nobody is homeless, nobody is hungry, but I think about dried towels, taxi lights and rain in front of the office kitchen dishwasher, one hand undoing the milk lid, shit coffee in the other.

I administer this nostalgia drug in a romantic way. I sit at a coffee shop in a hip part of town where no two chairs are the same. The coffee is delicious but there is always a lingering feeling of incompleteness so persistent I often wonder if I inflict it upon myself out of boredom.

I think about that as I scroll through Instagram on my way to work, and a desire for a life that revolves around glitter-painted star-drawn nails for Christmas bubbles up, a desire for a life that has space and enthusiasm for that level of detail, that has space for that. I never imagine myself in the future that way. Maybe a lack of optimism, maybe an imagination crowded with ideas that are not necessary or mine.

These are the kind of “now” thoughts, the sort of thinking you do when you’ll always get interrupted.

Now being the city, the next stop, the woman by the underground sign smoking, an unfamiliar accent maybe New Zealand, maybe Northern, the black man in a yellow striped shirt, the girl in the office whose waist is always constricted by a tight leather corset-belt, the smell of the carriage perspiring. The restless energy of everyone going somewhere.

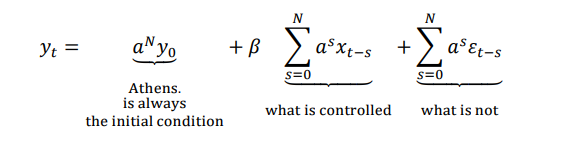

If you move fast enough the past and the future are only punctuated by place.

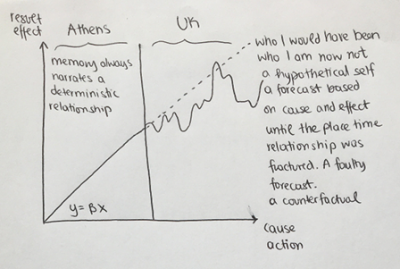

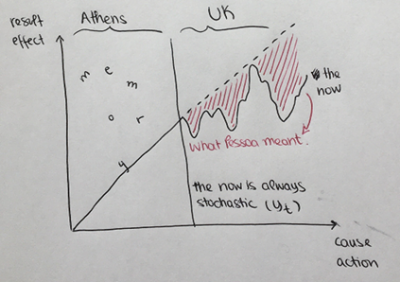

There is a certain danger to extrapolating the memory- fabricated greatness of the past, through a straight line projection, into the greatness of a hypothetical- counterfactual present.

The danger:

Fernando Pessoa says the best poems are those I’ve never written and what I think he means is the girl protesting could have always turned out bored or an afterthought, a child prodigy anti-climax devoured in this version of the story by staying rather than leaving.

What Pessoa meant:

When an immigrant, the UK Customs office and Migration Advisory Committee can tire the soul in ways different but with no direct metaphor for those of the Home Ministry of Labour rights, the Greek civil police, the legacy of feudal democracy.

You take your pick at corrosion.

When you skin the protest girl what do you make the skin into?

iii.

The background sound is the tube trudging its shell through the 1890 walls of its container. The background is a high pitched sound as if metal sheets deep inside the ground are on a high speed collision, in a clash that has no further consequences beyond smudging the pronouncing of the next stop.

The man opposite me on the tube fidgets relentlessly. On his lap rests open “Dead Famous” by Dick Lively. I wonder if this is Dick Lively himself, doing donuts on the tube like a live poster-advertising of himself.

I look at my legs in the curved carriage door lengthening in the reflection into themselves and I feel I am being carried to work in a giant teaspoon. If you don’t know why that is, I urge you to stop now and go look at yourself through one as if the teaspoon were looking away from you. I admire the small ankles, the thick heeled leather shoes I’ll run in when the doors open. Who do I look like today? Am I a convincing representation of myself? I want to be Joan Didion in the square, a black and white scarf tied around my neck. Something is instantly interesting about her. The man behind her wants to be what she is looking at with such reserved, dissecting curiosity. I want to be the woman with the intellectual infrastructure to look at the world with such curiosity on an unoriginal Monday morning. My love for Didion as an opposite place to “Monday morning”. Did she care about Mondays? Living in your own mind so grandly must involve some forgetting of time in the conventional sense. This is what it means to be a child but also what it means to be caught looking at the world in a way worth writing about.

When the doors open we all venture out of the teaspoon shoulder to shoulder, graceful-looking, like Jenny Odell’s ducks “placid-seeming, paddling strenuously, manically beneath the surface”. Our hands in our pockets are absent-mindedly typing emails and swiping past inappropriate men and women with small breasts.

One of the first books I read when I moved to the city was Nausea. The book perfectly described the void of urban living, the mode of being our machinery of prosperity had designed. I sat in my filthy room and surrounded by the sounds of my five flatmates seeping through the walls, I wondered if, “humping away at this life 360 days a year, some kind of repetitive injury of the spirit sets in” And if it did why didn’t anyone else but Sartre seem to get it.

On my lunch break, in the Pret a Manger queue (or other fast white collar eatery) Sartre would “glance around the room and think: What a comedy! All these people sitting there, looking serious, eating. No, they aren’t eating: they are recuperating in order to successfully finish their tasks” and so do I. This feeling was both devastating and exhilarating. It gave me the ecstasy of having discovered something important about the meaning of life and granted otherwise empty routines the depth of being on the verge of ironic. I could now ironically go to work or ironically order my £3.20 single shot latte every morning.

I talked to others about this but found that somehow in the epicentre of Sisyphean repetition talking about existentialism, seemed “dramatic”. My friend even remarked “how low your self-esteem must be”. In the London version of the myth, Sisyphus is carrying his rock around the circle line, maybe he’s British Ghanaian or British Caribbean or some other version of himself so rightfully belonging in this place, while the place murmurs otherwise in denial.

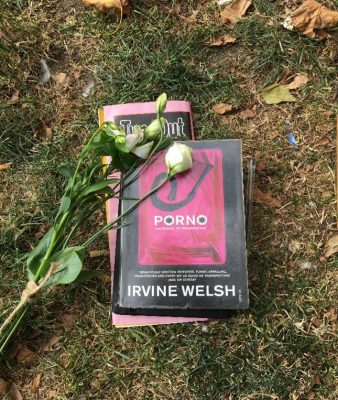

I use my commute for resistance. (You know what I mean by existentialism seeming dramatic because this sentence seems ridiculous to you, comical or pathetic.) Leaning against the yellow carriage pole squashed between houndstooth- and herringbone-carpeted human surfaces, an inch away from giving in to the madness of impulsively kissing a stranger I audaciously open Porno (Irvine Welsh of Trainspotting) and read out loud from page 146 “I believe in the righteous, intelligent clued-up section of the working classes against the brain-dead moronic masses as well as the mediocre, soulless bourgeoisie.”

I don’t actually. I just think it would be monumental if I did.

Oxford Circus desperately craves that kind of context denial.

I had a cry in Crabtree fields with Porno in my hands once. I had gone home the night before to find my belongings in a cupboard inside plastic bags and my middle-aged flatmate pretend-screaming down the phone supposedly to the police saying loudly through her door, whenever I came close to it to ask for my bags back, that she felt threatened. I thought about how, had my father been around, had I been in Athens, I’d have given him a call, we’d have had a good laugh about this, packed my stuff and left the looney for a minimum of one month of recuperative chicken soup and post 9pm right wing political debates at home. I would chill in the balcony looking at the “doll’s house” across and its clementine trees and slowly fuse back into remembering I was the fucking valedictorian and forget about the whole housing incident altogether. But he is not here and the landlord said it’s happened before and the council said if it’s not social housing they can’t do anything and the General London Authority rogue landlord service referred me back to the council so I just woke up the next day (the Porno in Crabtree fields day), put on my brogues, ripped open the plastic bags I had moved back into my room so the bitch had to get new ones to repackage my stuff while I was at work, and got on the tube.

At lunch I thought about my options, scrolled through my bank account contemplating the £1200 I did not have for a deposit and the prospect of crashing on people’s couches for a month while going to work regardless as if I had just kissed my stay-at-home husband goodbye and asked for sweet potato salad for dinner, seemed inevitable. I pondered over the number of lattes I had had instead of stocking up on impromptu homelessness savings, and it still seemed money well spent. I could not resist the feeling that this was always going to have happened here, that for the first time I wasn’t a student, for the first time this was not the rehearsal or the prequel to being the Greek Prime Minister or the next Kiki Dimoula, this was it, this was what it’s all been leading up to, life here, life here for me, what it was all about. I could not resist the thought I should have stayed in Athens, back then or gone back all those other times the urge to do so had come over me and some intangible higher ambition had stopped me, should have given in or give in now, and stop playing career cazanova in the city of homelessdom 1486 miles from home, with no pink house and no headroom to ignore the cracks. I thought about my dad still frozen in my high school valedictorianness, back home getting older while I was here failing to piece a deposit together, fighting with broken heating and disturbed middle-aged women and let the Crabtree field UCL professors grazing their broccolis around me, conclude I found Porno tears-on-a-public-bench moving.

(Image credit: Christina V Palmou )

When I first moved to the city, I lived in a house with a garage for a living room. One of its rectangular sides was a garage door and the floor was just cement. There was a gap under the door and cold air or water or whatever else could fit under there would make its way into the house. In the viewing the agent, an Italian guy no older than twenty-five, boasted on the walk from Canada Water station about his success in the city at such a young age. In the viewing he showed me the garage only in passing and urged me not to look too closely as works were underway for it to be converted into a living room by the time I moved in. When I moved in, I realised two couches had been picked up from a skip and thrown in the room was what he meant by works being done, tricking naïve people moving to the city for the first time into believing they would be renting a home from him was what he meant by success. Estate agents are the cowboy caste of London. It’s not their fault really. Misregulation breads rent extraction and rent extraction builds a concentration of returns accrued to idiots. This, and not the law of supply and demand, is in fact the first principle of economic theory. When I first moved to the city after six years’ worth of economics degrees, this was the first thing the city taught me.

When I moved in, the bathroom hadn’t been cleaned since the seventh day of creation. My room was next to the only bathroom for 5 tenants, and in the morning from about 6 to 9am, when the last person had left for work, the bathroom door would slam again and again and wake me like a ruthless,relentless alarm clock. The house radiators didn’t work until they did and for two months in the summer I slept at friends’ and lovers’ flats as the room was Tropics-on-Thames. My father said “Christina only people who don’t have another choice live like this”, surprised his legally immigrated junior white-collar daughter couldn’t do better.

I moved out with my first payrise. By that time, a year in, the living-room-garage had turned into an anything goes room, boxes of left behind possessions of flatmates that had come and gone, books and broken furniture scattered on the skip-couches or the floor. There was a brand-new fridge in the middle of the room, as if king of the trash, and I remembered how when I had first moved in some of my flatmates had complained the fridge was too small for 5 people. At some point the agent must have brought a new, bigger fridge in response and not fit for the miniscule-corridor-for-one kitchen of the house, left it there to buzz comfortably with the left behind, glow blue light against the dirty walls.

For the new place I had standards. The first search criterion in the flat search engine was 2 bedrooms 2 bathrooms. One additional flatmate at most, I thought, how bad can it be. When I met Evridiki, it seemed easy. The house was clean and tidy, the living room was a living room and she, timid, wrapped around her fluffy robe, laughed easy at my charming London jokes. In her forties, Greek as well, we shared horror stories of previous flatmates. They had all been very mean to her she said and I moved in straight away.

Evridiki worked from home. She had been an untenured academic for too long and often waited for me to come back from work to read me her work emails and tell me she hopes to meet the love of her life soon. For him she would drop everything she would say. She didn’t seem to have many friends but for four women she met once every two months for brunch from which she usually came back bruised. I booked tickets for us to go to the theatre and went for dinners together, offered to go out for drinks to meet this potential love but she always refused. About a year in, I came home, and she waited for me in the living room. She started screaming at me about the cleaner and then about the doorstops and then locked herself in her room. After that, I came home every night to something new. First, she separated the rubbish from the bin into my rubbish and her rubbish. The week after I came home to two of everything. By the sink we had two hand soaps and two dish soaps, four sponges. Another evening she hid the doorstops from all the doors, then threw my shoes from the rack in the hall into my room. Two weeks in, she started packing away my possessions when I was at work and hiding them in the storage room. Right before the fake phoning the police she made her – must have been now – seventy-something-year-old mother source my father’s number in Greece to tell him I was doing the drugs and not ironing or hoovering. “I raised my daughter to be a scientist not a housewife”, said my father and hung up the phone. “Christina get out of there, only mad people live like this”, he said to me.

K. came over that night, the screaming-down-the-phone-supposedly-to-the-police night. We threw teabags from across the room into cups for a while as the water was boiling for the third time over and it was ok. We devised a list of come-back goodbyes including olive oil in the shoes, hidden cupboard mackerel and sex on her bed but in the end ended up just making out on High Fidelity and a pile of T-shirts on the floor instead to remind either side of the wall that forced eviction does not deprive nor bring happiness. Consequence was for real life.

I got on with the packing. I stripped the bathroom of its toothbrushes and forever almost-empty coconut body butters, climbed on the kitchen counter to retrieve my juice maker wrapped timidly around its cable since I had moved in two years ago. K. threw banana peels at me, the mould weaved patiently its artless love affair with the wall, and I folded together everything, down to old crayons, leftover Christmas cards from a pack of 12 I had bought at uni, a Charleston feather headband blinking from its sequined skin since the office summer party, a spell of leftover selves, breadcrumbs of a life already consumed, a menagerie of items creeping up in drawers when all else is put away, cluttering a different shelf year after year too important to toss, too elusively used to have been packed away already. A list poem of a box. I wrote “miscellaneous” on the used cardboard box taped it up before I got too much into the items or the why I’ve been carrying them around like my own very special sequined cross up and down the country, hung a pair of coral earrings from the box to my ears and headed to the train station on the way to Shoreditch to celebrate being housing-bruised (and accommodationally challenged) and coming out the other end Cuba Libre in hand.

K. and I raced to the platform and watched the stops slide by the clock in neon orange letters as if place is another way to count time. As the train approached K. fake hug-pushed me to the tracks to the sound of the driver’s outraged beeping. His tall thin legs swayed right and left as he walked from far away an out-of-beat dance to the carriage.

The Canada Water Shoreditch line always has something meta about it. It traverses the purpose built, sterile residential into the extravagant and superfluous, an artery going from the stomach to the heart. The carriages are slow and large, the way an artery expands to sooth the blood flow. Going back and forth between where my packed boxes were and a Super Bock happy hour at Kick prequel to a drunk Cargo grind I’ve learnt the ride takes as long as for a chapter to get gripping, for a verse to start slipping in, as long as for time to be lost in a Proustian sense so as by the time the stop is announced one jumps in panic, clumsily awakened, momentarily not sure when or where, someone else’s left behind two-day-old madeleine wrapper accidentally in hand. Something seems to get stranded in the tunnels past Shadwell, in the orange and grey seats where a Glasgwegian homeless man commended Trainspotting on my lap one Thursday night and we all thought “Irvine Welsh in disguise!”.

Twenty minutes away K. and I are chatting over 3 parts Glenmorangie, CTC Sherry Blend and a scoop of chestnut gelato (otherwise known as the Rich-Creamy-Inerpit-Shack’s Stash) served in Bethnal Green with a spoon shovel that’s still clinging in my pocket from that night. Over Shack Stash K. promises to fry bacon in the kitchen with the fan off, windows closed, naked, long roll up on his lips for retribution. This is what youth resistance has come to look like I am thinking: Bacon smoking a bigoted 40-something-year-old who detests people but refuses to live alone out of fear of loneliness and the stern belief that to live further than a tube stop away from a John Lewis is not a life worth living.

My “knowledge worker” brain (a pop term for a non-university researcher) would say this is a domestically manifesting culture war, uninhibited by the fact the flat costs (what I’d qualify as) 110 hours of work at the mandated national minimum wage (at the time of writing this). If I were to work the worker-fought eight hours a day, at 40 hours a week it would take me almost three weeks to pay for a room in a house I can neither live in nor can the state, the landlord, the general London authority, the competitive private renting sector bother to do anything about. For so long as payments are made, the revolution is reserved for the crazy, the extremists, the scum manifestos prepared to shoot bright, once-in-a-generation artists in the spine.

As I swivel my drink in the drunken joy of middle class (what are the boundaries of middle class now defined by?) homelessness Rishi with his specially designed No 11 newsletter, his in-office dog pics (dog probably pooing all over the spring budget while taken) and John McDonnell jokes pops up on the screen from last week’s announcement when he’d promised to turn “Generation Rent” into “Generation Own”, as if I’d failed basic arithmetic back when I was 10.

As he signs off the email in a 1000-pound specially-commissioned Rishi signature logo, the words shine on the surface of a fridge that stands still with its mechanical buzzing in the middle of a garage living room, a lonely middle-aged woman hides in her bedroom having inconsequentially evicted another flatmate, the landlord calls on caller ID to trash you, the termites slow taste the wall, one third of the privately-rented housing stock doesn’t pass the government’s decency standards.