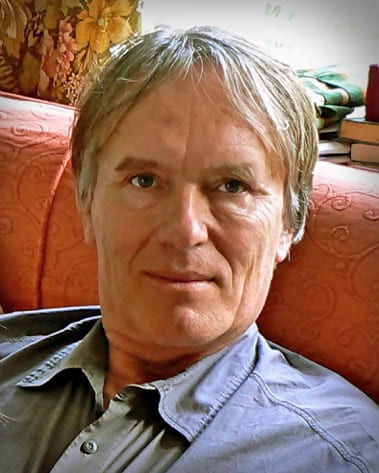

It is with great sadness that I must report that Bart Moore-Gilbert, Professor of Postcolonial Studies and English, passed away on 2 December 2015, after a shockingly swift illness.

Anna Hartnell, Bart’s wife, sent the following message to his close colleagues in the Department of English and Comparative Literature and the wider College community:

“As many of you will already know from reading Bart’s blog, Bart died on Wednesday at Trinity Hospice, surrounded by people who love him. The cancer progressed rapidly in his last weeks, and the speed of his decline was unexpected. Thankfully he hung on long enough to see the birth of his son Luke, and also to see his brother Ames again, who arrived the previous Friday from California.

“Thank you for the very kind messages that many of you have sent. They are a real source of comfort at a very difficult time.”

Bart Moore-Gilbert joined Goldsmiths in 1989 and, over the years, taught modern, contemporary and postcolonial literature. By the time he retired, at the end of August, he’d been at Goldsmiths for 26 years. He will be remembered by his colleagues for his dry wit and his intolerance of the increasing bureaucratic demands made on academics. He sometimes took controversial views, but he was in many ways a shaping force within the Department, having directed the External Degree for many years and having developed Postcolonial Studies.

Dr Carole Maddern, medievalist and lecturer in ECL, recalls the moment when she first met Bart, on her third day working at Goldsmiths:

“He popped his head around my door, introducing himself, and asked in that gentle way of his, whether I’d like to contribute to the External Degree Programme. As Programme Director, he offered lots of support and guided me through the early drafts of a chapter which led to my first publication. Twenty years later, my own involvement with the External Programme is still evolving and expanding and I’ll always be grateful for that initial opening. The ongoing success of what has become the University of London International Programme in English is one lasting tribute to Bart, who established the department as the Lead College.”

Dr Mairi Neeves, who was supervised by Bart and now teaches postcolonial literature and theory in ECL, remembers him as an inspiring mentor:

“He was the ultimate academic, who always seemed to be writing, and pursuing new projects and ideas with a ferocious and passionate intellect. But like all the best, he cared a great deal about those he taught, respected our ideas, and wanted us to succeed. As a teacher and PhD supervisor, he gave me a lot of time and attention. He taught me that the main limitation of my work was not in my creativity and ideas, but at the level of structure – this was a huge breakthrough for me and a pearl of wisdom I have since passed on to many of my own students. He was rigorous academically and had high standards; praise from him would be highly valued because I knew I had earned it. I felt confident under his supervision and I still often think of what he would say to a particular line of argument or expression. He really cared, and that was the most inspiring thing of all.”

The tireless pursuit of his research is evidenced in his many publications. His first book was Kipling and ‘Orientalism’ (1986); this was followed by his influential Postcolonial Theory: Contexts, Practices, Politics (1997), translated in several languages, including Korean and Chinese; other works include a monograph on Hanif Kureishi (2001), and a study of life-writing, one of Bart’s other major interests: Postcolonial Life-writing: Culture, Politics, and Self-Representation (2009). He collaborated with colleagues inside and outside the Department and the College too; the very popular Postcolonial Criticism Reader, for example, was co-edited with Gareth Stanton, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Media and Communications, and Willy Maley, now a Professor of Renaissance Studies at the University of Glasgow.

Of Bart’s single-authored Postcolonial Theory, Dr Stanton comments that it was “a very clear exposition of the state of play in the emerging field as we moved into the new millennium and I remember Bart’s delight on receiving an unsolicited letter from Terry Eagleton telling him that it was the clearest exposition he had read up until then of the work of Bhabha, Spivak et al.”

His research and teaching interest in life-writing eventually materialised in a different form too, when he wrote – initially as a creative writing PhD student in the Department of English and Comparative Literature, under Francis Spufford’s supervision – his widely acclaimed The Setting Sun (Verso, 2014), a memoir of his loving father and of the violence of Empire, and the unresolved tension between personal memory and historical record. Dr Stanton recalls:

“My last contact with him was an e-mail written in the middle of the night at Mumbai airport penned in an approximation of certain flowery versions of Indian English to be found on the subcontinent praising him for his last autobiographical work tracing his father’s career in India. He replied with great humour in similar tones. I was very sad indeed to hear the news of his passing.”

Dr Benjamin Woolley, also a former student of Creative Writing and Associate Lecturer in ECL and a friend of Bart’s for many years, remembers him:

“Never mind the lecture theatre or seminar room, walking down a street or sitting in a café with Bart Moore-Gilbert was an education. I have known him around twenty years, but never ceased to wonder at how he would salute a procession of people passing by—shopkeepers, stallholders, waiters, bar staff and baristas (we shared a love of pubs, coffee shops and cheap local restaurants), tramps, street sweepers, police constables. Sometimes he would hail them in English, but as often in Swahili, French, Spanish, Urdu, Pashto or Arabic (I’m guessing – I had no idea most of the time). Whether fluent or not, he would dive into London’s impossible diversity in any language that came to his tongue, and the looks of delight, and sometimes bewilderment were a source of constant wonder, and always left me with a feeling that this is a proper man of the world.

“His flat was close by in Battersea, perched atop Lavender Hill. He had erected a terrifying roof terrace next to the chimney stack. We would stand there together, dizzy with Georgian wine and vertigo, and watch the travel networks of the globe converge – Heathrow’s flight path overhead, Clapham Junction and the jams on the South Circular beneath (though not the Tube, obviously – we are in south London). An enormous Asda was behind him, the glinting towers of international finance ahead. And he would tell me stories of his upbringing in Tanzania, of trips to Zanzibar, researches in the Bombay archives, meetings with Palestinian radicals, swimming in Saint-Girons and walks in the Pyrenees – a genuine man of the world.

“In his final days, he read Thomas Hardy’s poems and told me they were consoling. One can only hope they were effective as we witnessed a quick decline, met with heroic forbearance and creative energy touched with justifiable irritation. Our last meeting was in a café next to Battersea Arts Centre, where he enjoyed a salad of pistachio and pomegranate while I tucked into a bacon sandwich. He knew the owner, naturally. He didn’t feel up to a conversation in whatever language she spoke (I’m thinking Russian), but he exchanged a smile—the universal language of anyone of the world.

“As Hardy put it, life laughs onward. But I will miss him, his compassion, his politics, his deadpan humour, his erudition, his hats. I will miss his polyglot tongue, as will the shopkeepers and stallholders. Students will miss him, the academy will miss him, the world will miss him.”

Ben’s words reminded me that I discussed Hardy’s poetry with Bart in my first year at Goldsmiths, in 1995 – we taught on the same course, which spanned literature from 1895 to 1920. I wasn’t too keen on Hardy, but Bart saw in his poetry what I did not. I must go back and read those poems again.

A memorial service was held for Bart on Tuesday, 15 December 2015. Bart left detailed instructions as to the kind of send-off he wanted and was keen that it should be a celebration. He asked that people didn’t send flowers and that any donations go to Medical Aid for Palestinians or Kidney Cancer UK, which recently merged with James Whale Fund for Kidney Cancer.

Bart is survived by his wife Anna and his children Madeleine and Luke, who was born just a week before Bart’s death.

Originally posted on 10 December 2015 by Professor Lucia Boldrini, Head of Department, English and Comparative Literature.