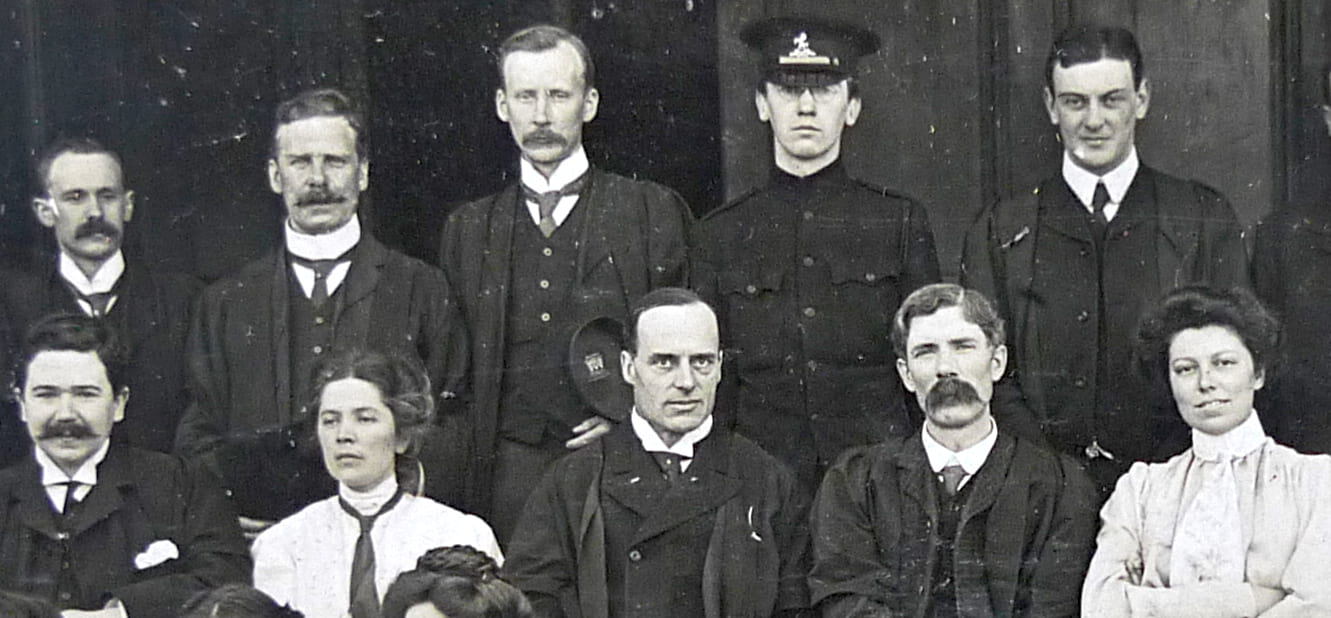

Caroline C. Graveson, first Woman’s Vice Principal of Goldsmiths’ College, University of London on her appointment in 1905 with the women staff. Centre front row. The picture was taken at the entrance to the women’s corridor on the east side of the building

Caroline Graveson’s appointment as women’s Vice Principal of Goldsmiths’ College in 1905 received national newspaper exultation.

The Daily Telegraph and London Evening Standard said ‘it was one of the most valuable and important among those now open to women.’

Some of Caroline Graveson’s first women teacher training students in 1905-6.

She remained one of the most important women in British Higher Education during the Edwardian period, through the First World War and continuing through the 1920s and 30s until her retirement at the end of 1934.

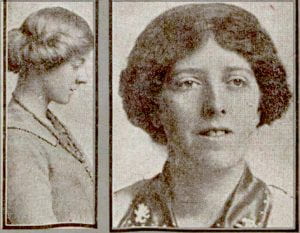

A typically distracted pose of Caroline Graveson in group photographs

During the Great War, Goldsmiths became virtually an all-woman’s place with most men students and staff joining the armed forces. By 1916 the roll call of students was 268 women to 20 men.

It was a pioneering training college centre for educating teachers because it was the first to be co-educational and non-denominational. This meant it could admit students with non-Christian backgrounds such as Jews and Muslims, and it partnered with the prestigious Art School and thriving adult evening educational programme started by the Goldsmiths Company’s Technical and Recreative Institute in 1891. It was also run by the University of London- the most important and influential university in Great Britain outside Oxford and Cambridge.

Caroline was one of the first women members of the British Psychological Society- a reflection of the College’s commitment to researching and teaching educational psychology.

She spoke fluent German because she had been a student at German universities for 2 years between 1896-98.

She wrote several books during her career, and was one of the leading Quakers in the UK.

She was also an international traveller with trips to Algiers in 1913 and the USA in 1938.

She was also an international traveller with trips to Algiers in 1913 and the USA in 1938.

Caroline could be described in modern terms as a quiet feminist radical who travelled the country attending speech days at state secondary schools to encourage girls to be ambitious. She wanted them to challenge the public school domination of the professions and elite institutions.

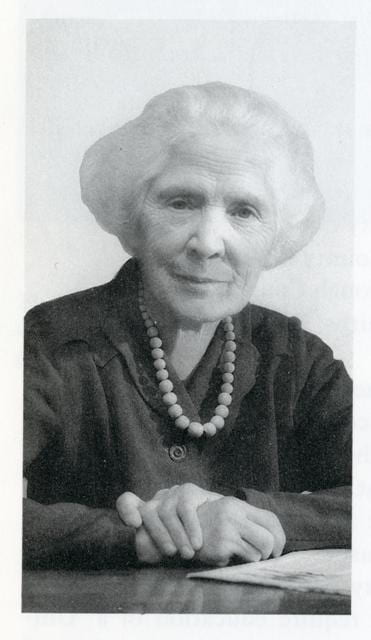

Photographs and written accounts reveal a person who was physically small, slightly built, who did not dress or live ostentatiously, but had a voice described as ‘superb’ with perfect elocution.

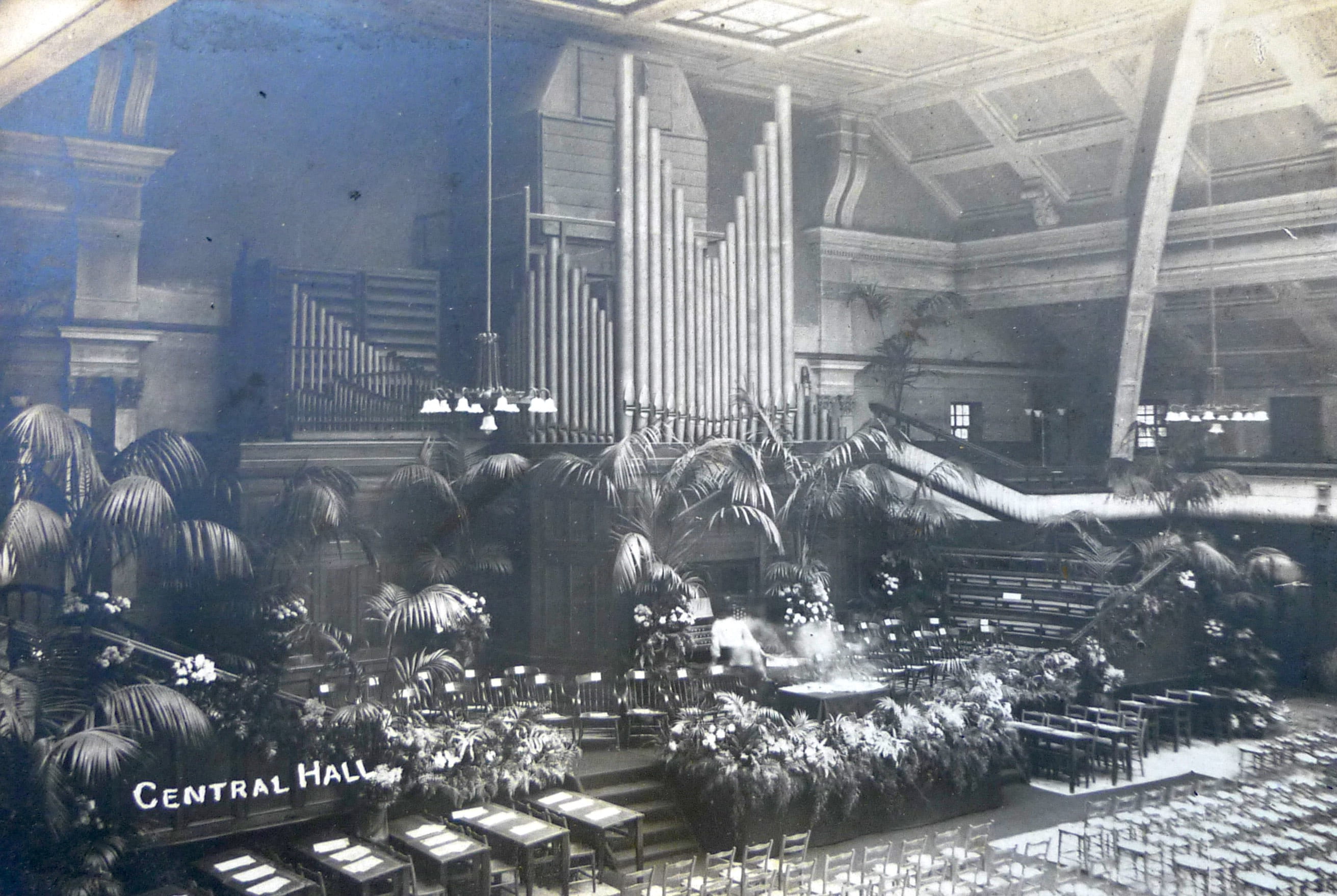

This enchanting voice ‘could, without the microphone, penetrate to the remotest corner of the Great Hall of Goldsmiths’ College.’

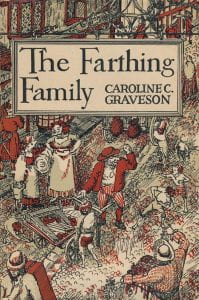

Hymn and libretto writing

Caroline wrote the words for the College hymn sung at the morning assemblies held in the Great Hall for over fifty years.

Original score for ‘The Smiths’ Hymn’ signed by the composer Leonard Rafter.

The lyric was inspired by a passage from Ecclesiasticus XXXIX 28 about the spiritual creativity of the blacksmith fashioning the future with hammer and anvil.

She was an expert on the Old and New Testaments writing three books before the Great War on ‘Lessons on the Kingdom of Israel’, ‘The United Monarchy of the Hebrews’, and ‘Lessons on the Kingdom of Judah.’

Her writing was romantic and hopeful about the teacher’s role in conjuring ‘countless forms of beauty’, perfecting the ‘golden enterprise’, before ‘dreaming eyes’, and seeking to ‘fashion children for a finer, nobler land.’

This was Goldsmiths’ College’s version of William Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ where the ‘Smiths were working on’ in the midst of desperate urban deprivation and poverty to build their own ‘green and pleasant land.’

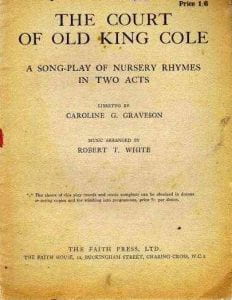

She also wrote the libretto for R.T. White’s composition ‘The Court of Old King Cole’ first published by Faith Press in 1914 and revised in 1952.

Faith Press in 1914 and revised in 1952.

It was a kind of jaunty two act children’s nursery rhyme opera.

Caroline Graveson was a woman who acted, moved, decided and directed with quiet and concentrated dignity.

Caroline’s memories

This is evident in two powerful memories she offered in the college’s 1955 history titled ‘The Forge’:

“One vivid recollection I have of the German Zeppelin flying low over our college field, of the women students in gay summer dresses running out to look at it, and of urgently shouting them back to shelter. We had not yet learnt to look up at the sky for danger.”

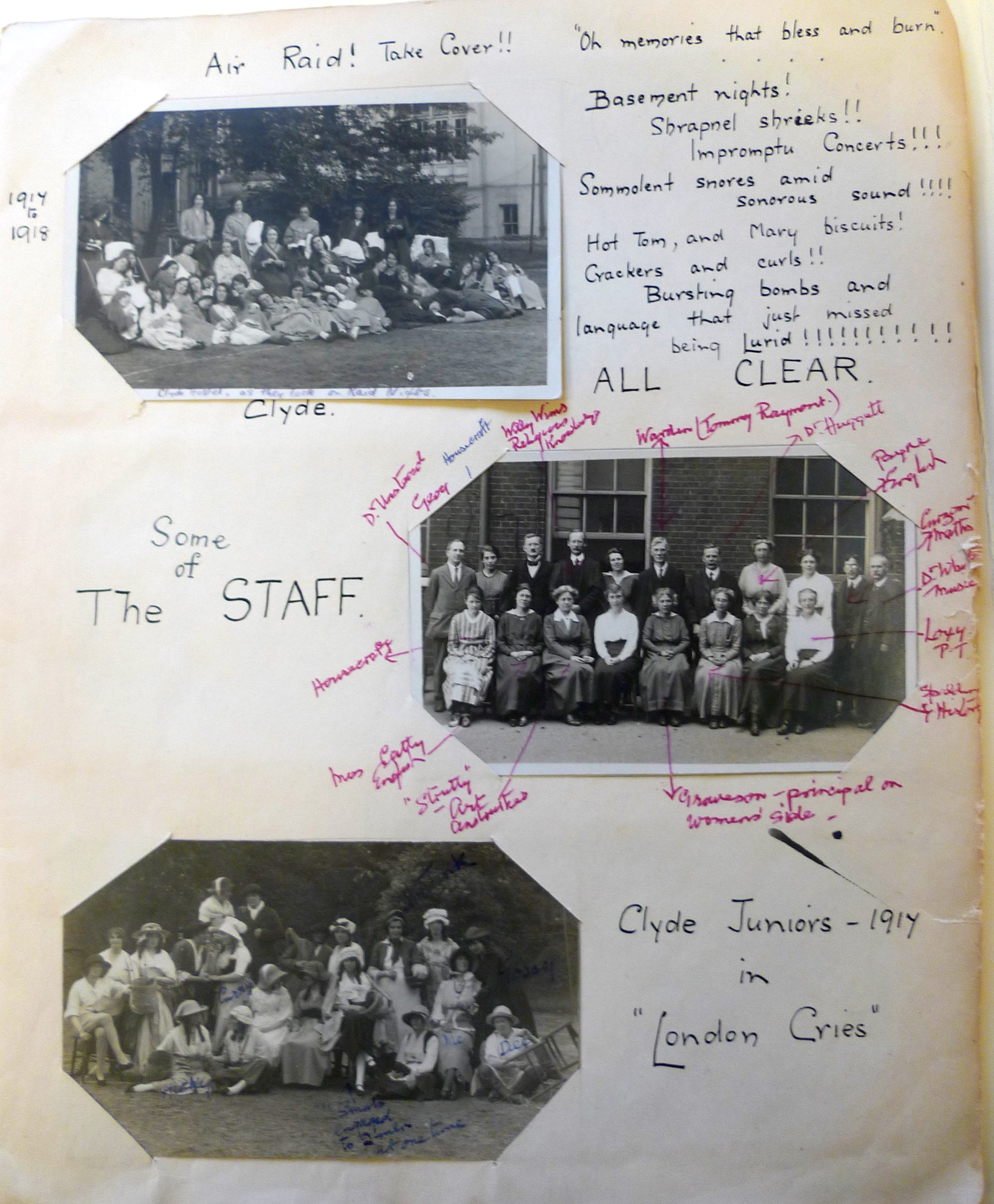

One of Caroline’s students, Kathleen Porter, kept an evocative scrapbook of her time as a student at Goldsmiths during the First World War, and her remembrance of the cry ‘Air Raid, Take Cover’ is just one example of the caring and effective leadership the women’s Vice Principal set her students.

Illustration of Zeppelin raid in UK First World War recruitment poster.

Caroline Graveson was also a pioneer of progressive education that baulked at over-disciplinary and retributive regimes of punishment:

“One day in 1905, sometime before the Opening, as I was working at my desk in the woman Vice-Principal’s room, an elderly naval man walked in unannounced. He looked surprised to find a female in possession, and apologised by saying that he only wanted to re-visit the scene of his many thrashings as a boy at the Naval School. He told me that in those days my room was the Headmaster’s room, and the cane kept in its corner cupboard. I had heard of the terribly harsh treatment of the young boys in the school, and felt like disinfecting the room.”

Family background and education

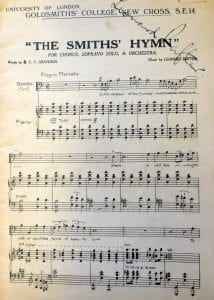

Handwritten staff profile for Caroline Graveson.

Caroline Cassandra Graveson was born into a Quaker family on 16th June 1874, and was one of six children of Michael T Graveson and his wife Hanna. They ran a grocer’s shop in Liscard Village, Birkenhead near Liverpool.

It must have been a successful enterprise because the 1881 census shows Mr Graveson was able to employ an 18 year old apprentice grocer, George Cooper, who was living with them along with two servant girls aged 16 and 21.

Caroline and her three sisters all pursued professional teaching careers and remained unmarried.

It is problematical to apply contemporary understandings of gender and sexual orientation to individuals and social situations of more than 100 years ago.

It may be the case that these impressive women decided that their commitment to public service and teaching was far too important to sacrifice on the altar of romantic entanglements and marriage. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries women faced a discriminatory marriage bar in the teaching profession which meant they had to surrender their careers on marriage.

Caroline’s education and professional career paralleled the immense struggle for equality and the right to vote by the women’s suffragist and suffragette movements.

It would not have escaped the attention of women staff and students at Goldsmiths in June 1914 that the first cousins of the architect of the new Art School block, Sir Reginald Blomfield, had infiltrated Buckingham Palace to stage one of the most dramatic suffragette protests of the time.

Mary and Eleanor Blomfield, WSPU activist first cousins of Goldsmiths’ Art block architect Sir Reginald Blomfield.

The Daily Herald reported that instead of ‘passing the Royal Presence with the customary abject attitude’ Mary Blomfield ‘fell on her knees and cried out in a loud, shrill voice that penetrated the limits of the Throne Room “Your Majesty, Won’t you stop torturing the women?”‘

The orchestra was ordered to play louder as she was bundled away by royal attendants. The newspaper reported that the sisters had been able to gain entry to the event because they had previously been presented at court. They were described as ‘ardent suffragettes and students of Persian Philosophy.’

By 1939 Caroline Graveson was living in Malvern Worcestershire with her older sister, Bertha, who started out as a teacher and then became a hospital almoner, a pre-NHS forerunner of a hospital social worker, and her younger sister Hannah, a retired teacher and nurse. Her oldest sister Agnes had also been a teacher and was living in Hoylake, Cheshire, though was described as ‘incapacitated’ through ill-health, and died in 1943.

Caroline was educated at the famous Friends boarding School, Ackworth in Pontefract, Yorkshire, the Jersey College for Girls in St Helier, Jersey in the Channel Islands, and took a first class degree at University College, Liverpool between 1892-96 which in those years could only be validated by the University of London.

For the next two years she travelled and studied in Germany where she gained fluency in German while at the University of Jena.

She gained her first class Teacher’s Diploma and distinction Frobel certificate in theory and practice at Cambridge Training College between 1898-99.

She began her lecturing career at the University of North Wales in Bangor moving onto the University of Liverpool between April 1900 and September 1905.

Personality and character

In college archive photographs it has to be said Caroline does not indicate that she very much liked being photographed.

She is always pulling a face, looking in the distance, or away from the camera.

Caroline Graveson sitting second row fourth from the left in 1911.

A former student G.R. Lloyd who did his teacher training between 1923-25 said:

“The sound of Miss Graveson’s beautiful voice reading a passage of great prose, or giving one of her erudite and finely constructed talks would also impress me immensely and send me away with the feeling that the day had indeed begun.”

But behind the diffident mannerism and mellifluous voice was an acute concentration on human character and a mischief she would often deploy to advance what she thought was right and fair.

This is evident in the minutes of a staff meeting held 28th February 1907 which was discussing how to deal with the ‘rustication’ of minor misbehaving students.

Most of the men appeared to be advocating draconian measures.

Caroline’s ally, the kind-hearted and soft-natured Vice-Principal for men, Tommy Raymont, complained that the proposal was ‘brutal.’

Caroline deftly explained that women students should have to be dealt with by women staff and vice versa.

She then discharged the heat from the discussion by suggesting a stop-gap step beginning with a meeting before the Vice-Principals before any kangaroo court style committee trial process.

The issue fizzled out and was not followed up in future meetings.

In July of that year she was invited to a prize giving ceremony at Leamington Spa Secondary School for Girls.

She noticed the array of male local government dignitaries soaking up the pride of being appreciated for supporting state funded education for girls.

The first women students of Goldsmiths’ College lodging at one of its nearby hostels.

Caroline was there as a pioneering role model of achievement and assured them: ‘How better you are going to be than your grandmothers.’ She hinted that in order to succeed they would have to work harder then boys: ‘Avoid drifting along learning a little here and a little there. Make an effort to do over and above what is required.’

She finished her address by recommending that the school’s managers give all the girls and their teachers a day’s holiday as a reward for their great achievements.

The motion drew rapturous applause, particularly from the students, and became something of a fait accompli.

Kathleen Porter’s scrapbook from the time she was a student at Goldsmiths during the First World War. Her middle annotated photograph of ‘Some of the STAFF’ includes Caroline Graveson sitting front row fourth from right. Again she looks unassuming and hardly noticeable.

Another former student, L.R. Reeve remembered that she was ‘one of those exceptional women whose integrity, judgment, fairness, and dignity were suggested immediately one met her, and one always felt that any of her interpretations was likely to be the right one.’

In the memoir he added:

“Then, too, she was fearless in her decisions. She wouldn’t, she couldn’t, choose an easy way out of a difficult situation. Her self-respect permitted no relaxation, and compromise was possible only when no principle was involved.”

Some of Caroline Graveson’s first women students training to be teachers at Goldsmiths’ 1905-7 and holding tennis rackets and hockey sticks.

The leading Japanese psychiatrist, Kamiya Mieko, recalled meeting Caroline at the Friend’s House in London in 1939 and after being taken by her to a vegetarian restaurant she recalled:

“How warm and pure was her love towards me. She rejoiced with me that a way had been opened for me to become a doctor. She added, however, that I would probably turn to psychiatry later.”

Goldsmiths Old Students’ Association Yearbook for 1935 said:

“…her gracious personality, her impelling influence and her complete devotion to the College will be an abiding memory to us all and particularly to the women students (nearly 5,000 of them) who have known her as their Vice-Principal.”

Caroline Graveson was clearly a self-effacing individual who put her public service and concerns for others way before herself.

Sports day at Goldsmiths College 1905-6 before the building of the Blomfield art block that closed the open quadrangle looking out onto the back field.

She always lived simply. Despite being appointed with a salary of £540 a year in 1905, which is the equivalent of £60,250 at the time of writing, the 1911 census reveals that she was boarding at 33 Gordon Square in Bloomsbury.

She made no effort to demand any increase in her salary from 1908 to 1920.

And it is also significant she was paid about 17 per cent less than her male equivalent.

Some of the first women students at Goldsmiths’ College lodging at the Kent Hostel.

In 1922 the College delegacy minutes reveal that her doctor recommended she needed six months rest due to ill-health.

She was 48 years old and had endured all the stresses and grief of trying to save the college from closure with her colleague Tommy Raymont during the Great War.

Sports day on the back field in 1908 after the completion of the Blomfield building accommodating the Art School. Men and women in Edwardian dress.

She had written sorrowfully of how she had to deal with the trauma of the first Warden’s death at Gallipoli in 1915, and then the equally tragic death in action of the highly popular English lecturer Billy Young:

“The First War dealt a heavy blow at the College. The loss of our Warden, of Mr Young and of many students deeply over-shadowed those left behind. I recall going down to the College (it must have been a Saturday afternoon) to break the news of the Warden’s death to the women students, who were having some sort of impromptu dancing in the Great Hall. I asked them all to be present at Monday morning’s Assembly and they silently left the college.

Caroline Graveson front row second from the left sitting beside Warden William Loring killed in 1915. English lecturer Billy Young, another treasured colleague, standing back row on the far right was killed while serving in France in 1917.

I remember how strangely empty and desolate the place felt when they had gone. I remember, too, making the journey into Buckinghamshire to consult with Mrs Loring about the Memorial Service, and how heavy with sorrow and foreboding seemed the late autumn countryside.”

Times continued to be tough after the 1918 armistice.

Memories and herstory

When the college was preparing to celebrate its 50th Jubilee in 1955, an editorial committee discussing and deciding content for the college’s first history book decided that Caroline should be commissioned to write Part III ‘Daily Life In College.’

True to her democratic and inclusive spirit the section became something of a style of broadcast programme where she linked presentations of contributions from students and colleagues who had worked and lived through the half century of college life with her.

Because despite retiring at the end of 1934, she was still centrally active in the students’ association and her professional career continued with her election to the presidency of the Training College Association.

Her ‘links’ in ‘The Forge’ are lively and characterful descriptions of the atmosphere of those first years:

“The building was entirely in the hands of workmen, and we moved from one corner to another of the Great Hall, as chips of plaster fell on us and our previous time-table then in the making. In those days one looked out from the windows of the passage behind the Gymnasium, across the Quad into the field.

The Great Hall adorned with decorations for the grand opening in September 1905.

Dear, unwieldy, spacious, dusty buildings! Even your oddities proved useful to us. The mezzanine corridors were ghostly wastes of space, but very convenient for lecturers to hurry through when the ground-floor passages were crowded, and opening into many small, low-ceilinged rooms, useful for staff studies. There were unexpected, tucked-away little rooms and for the first year or two, whenever more space was required, I went exploring with a pass-key and always found a cubby-hole that would serve.”

Despite being ‘co-educational’ there was gender segregation by prefect patrol.

Women entered and left by their own entrance on the east side. Men on the opposite west side.

A scene from the first Goldsmiths’ College library situated on the upper floor of the main building. A woman student is concentrating reading a book while a man in plus fours looks somewhat furtively behind the racks of newspapers, periodicals and magazines.

There were separate common rooms. Integration would be achieved initially through teas, clubs and societies:

“In those days women students came to College in gloves and were liable to faint. Had one of them appeared in the street in the short skirts of today (1955) , or – simply scandalous – stockingless and hatless, she would certainly have been followed as a laughing stock. We might be bent on making history, but meanwhile we had to prove we could live well in the present.”

Teacher training consisted of a two year programme for students without a degree until 1962.

They called themselves ‘Aborigines’ and were among the first women students at Goldsmiths’ College. In this group photograph you can see the faces of other women students pressing against the window-panes on the left to watch the photographer at work or trying a version of ‘Edwardian photo-bombing!’

The first year was packed with English, French or Mathematics, History, Geography, Science in some form, Handwork or Needlework, Drawing and Physical Education:

“They had lectures almost without pause from 9.45 a.m. to 5 p.m. Every student by order of the Board of Education had to learn 200 lines of poetry by heart. If I remember rightly, Wednesday afternoon was free for all; though later, owing to rivalry between men and women for the playing field, the men took Wednesday, and the women Thursday afternoons. It was touch and go whether the College should meet on Saturday morning also, and I was always grateful to our Jewish contingent for making this impossible.”

Between the wars, Caroline recalled the college filling up with men to almost bursting point.

Men were coming back to ‘Civvystreet’ from the armed forces and those taking up teacher-training 1919-21 could not be found enough accommodation. So the College’s ground-floor teaching room number 14 becoming a temporary hostel:

“As was to be expected, the men just released from Army discipline were in high spirits, and I remember an eruption of arm-linked men into the women’s corridors, and being accidentally knocked down. I heard, considerably later, and with some amusement, that Mr Raymont (now the Warden) had used the enormity of knocking down Vice-Principals as his text to an address to this army of invasion.”

All Goldsmiths’ College students had to dine at lunch-time at long tables with the staff sitting at a top table under a huge coat of arms. There were separate sittings for male and female students. True to the patronymic values of the time, the men had their lunch first, though the situation changed by 1914 when they were outnumbered 20 to 1.

Caroline Graveson also recalled sitting furiously ‘doodling’ on the blotting paper in unspoken sympathy with young women being interviewed by all men local education authority committees:

“Does any old student interviewed early in the first war recall the patriotic elderly gentleman who asked each candidate in turn what she would have done if she had been born a man; and the student who, after some moments’ consideration replied: ‘Well, I suppose I wouldn’t have been an Infant Teacher.'”

Post retirement influence

The Warden of Goldsmiths’ College from 1953 to 1974, Ross Chesterman had close connections with Caroline Graveson and speculated that this may have smoothed his path during the early and rather difficult years of his appointment. In his 1998 book ‘Golden Sunrise’ he said:

“She was a distinguished person and a very strong character with, I soon discovered, almost unlimited influence in College affairs. As I have said I had myself been for many years a member of the Society of Friends (a Quaker) and Caroline, like me, lived in Malvern where we both attended the same Meeting of Worship, and where she was an Elder of the Meeting. We were close friends.”

Caroline Graveson in her senior years.

When the college held a reunion of ‘The Aborigines’ with a planned dinner for 1,000 alumni in the Great Hall in 1954, she stayed overnight with the Chestermans at their home in Eltham:

“Her actual visit to our home can hardly be described as a total success because John, our son, was at a difficult stage and was not very pleasant with the somewhat strict Caroline. No harm was done, though Caroline did say she thought John was rather spoilt.”

While the domestic scene had been rather frosty, the professional connection in the College proved to be very promising:

“…at College she was in her element, and did a lot to make the day a success. The fact that Caroline appeared to like me was naturally an enormous help in my relationships with the old students and the present staff. I am quite certain that this scuppered any plans by our local communist cell to make life difficult for me. From that day I no longer had to be afraid of a hostile attack from the rear, as poor old Price (the previous Warden) had had to put up with during the whole of his short stay at Goldsmiths.'”

Ross Chesterman argued that Goldsmiths’ first students ‘were charming old people, even if some were reactionary in their educational views.’ He added:

“I’m afraid that after a few years when I began building – extending and altering the College and bringing standards up to something acceptable – the old students were less forthcoming, and soon became bitterly opposed to any changes from the Goldsmiths’ they had known and loved all those years ago. Apparently they liked it looking tatty and depressing.”

But if the older generation were set in their nostalgic and Edwardian ways, Caroline Graveson remained an advocate for social progress and equality.

In a speech to the Malvern National Council of Women in 1943 on ‘Education and Social Class Distinctions’ she advocated an expansion of the Secondary School system so that elementary education could be widely extended to state pupils until the ages of 16 to 18. She complained that:

“About 80 to 85 per cent of the better paid positions in this country are occupied by people from the Public Schools. England was the only country in the world where a public school education served as a means of entry to a club or society.”

First history of Goldsmiths’ College published in 1955 to commemorate its first half century of existence.

She agreed with her fellow speaker Dame Elizabeth Cadbury that the war was acting as a great leveler, and it was going to make for a very great fellowship in peacetime.

Caroline Graveson passed away in Portsmouth in 1958 in her 84th year.

It would be 59 years before the College would recognize her contribution to its legacy by naming a building after her.

She signed off her collaborative section of the 1955 college history by quoting from her hymnic lyric.

The old-fashioned language and metaphor is, or course, somewhat lost on the present 21st century generation of students studying and researching at a ‘postmodern’ university:

“The ‘Smith still works at his forge, and those of us who set him there, and those who so valiantly re-established him there (after the Second World War) unite in the same prayer that he may ‘set his mind to finish his work and watch to polish it perfectly.'”

Goldsmiths College as it was in 1905-6 when Caroline Graveson took on the role of Woman’s Vice-Principal.

Written and researched by Professor Tim Crook.

All images strictly copyright of Goldsmiths, University of London. All rights reserved.

That’s So Goldsmiths– a forthcoming history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.

Goldsmiths History Project Podcast by Professor Tim Crook