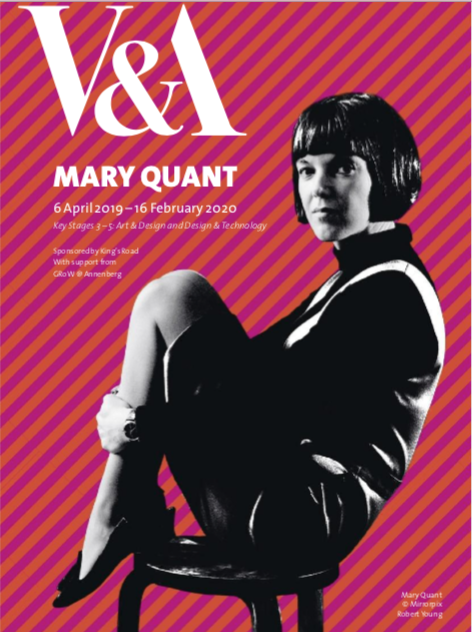

Dame Mary Quant has been hailed as the fashion genius who changed the way people thought, felt and looked in Britain.

After her passing at the age of 93 on 13th April 2023 she featured on at least 10 of the front pages of the UK’s national newspapers with tributes such as the ‘Designer who revolutionised British fashion in the 1960s’, and ‘The 60s high street fashion trailblazer’ who ‘blew the doors off fashion as we knew it.’

The headlines reflected her iconic status: ‘Farewell, Ms Miniskirt’ (Metro), ‘Pioneer of mini-skirt who shaped Sixties’ (Express), ‘Visionary British youth culture pioneer and 1960s fashion icon’ (Financial Times), ‘Fashion owes so much to her” (Guardian), ‘Farewell to the queen of fashion’ (i newspaper), ‘The genius who invented modern fashion’ (Mail), ‘Revolutionary Quant’ (Scotsman), ‘Mini skirt queen Mary’ (Star), ‘Farewell, contrary Mary’ (Telegraph), ‘fashion designer who popularised the miniskirt and created a liberated look for young women that defined the Swinging Sixties’ (Times).

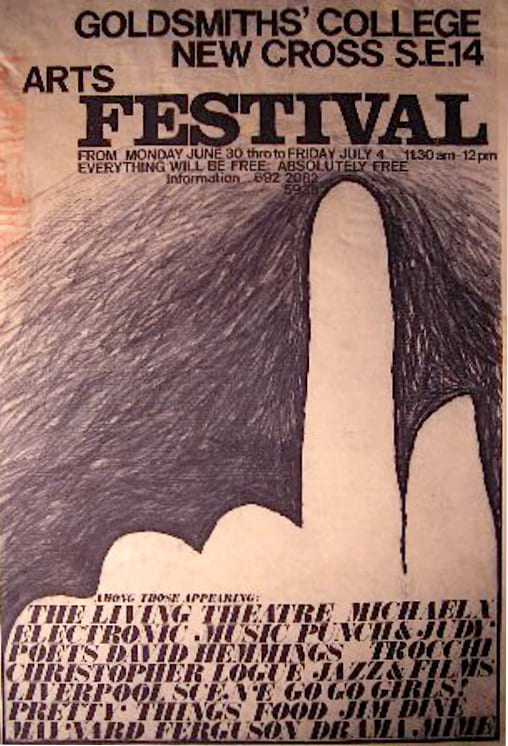

In her two autobiographies, Quant by Quant, first published in 1966, and Mary Quant Autobiography, published in 2012, she started with her time at Goldsmiths and the years she pursued her passion for art and design in The Goldsmiths’ College Art School of that time.

She celebrated her dramatic and stylish first encounter at a Goldsmiths Christmas Arts Ball with her first husband and partner, the aristocrat Alexander Plunket Greene and she relished talking about the influence and experiences with the avant-garde world that Goldsmiths opened up for her.

She was taught by leading modernists and surrealist artists, designers and illustrators such as Sam Rabin, Betty Swanwick and the legendary embroiderer and textile artist Constance Howard.

She was surrounded by fellow disruptors and cultural subversives- the notorious art forger, Tom Keating, who dedicated his talent and painting career to expose the capitalist greed of the art world, and Quentin Crisp ‘The Naked Civil Servant’- writer, illustrator, actor, and artist’s model. The celebrated abstract artist and designer Bridget Riley was another contemporary student.

Mary Quant would always remain a friend to Goldsmiths. On 23rd September 1993, she returned to receive an Honorary Fellowship and her advice thirty years ago to the graduating students in the Great Hall of the Richard Hoggart main building remains prescient in the present day.

She predicted the impact and significance of ‘the knowledge explosion’- which is now the digital information age of artificial intelligence, the implications of people living longer, and the need to be flexible and seize the opportunities of the future.

Mary was born Barbara Mary Quant in Blackheath in 1930 to high achieving parents, Jack and Mildred from tough working class backgrounds in Wales. They both gained firsts at university and became teachers- her mother actually lectured at the London College of Fashion.

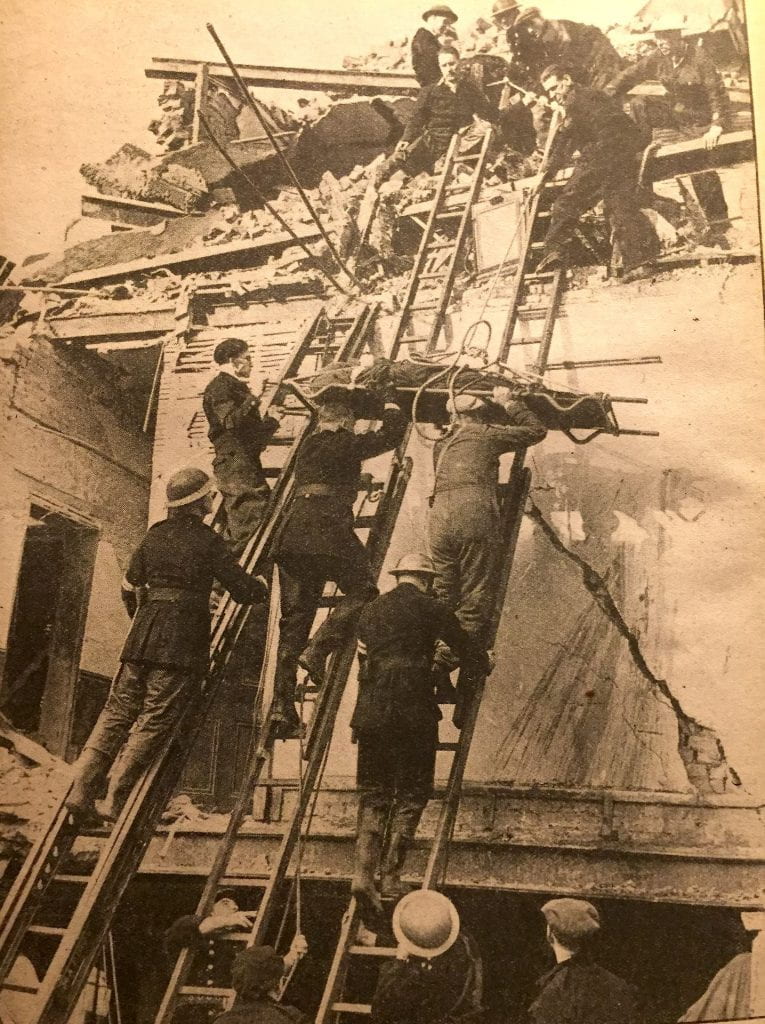

Her family evacuated to the Kent countryside during the Second World War where she witnessed the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940.

Mary Quant in 1966. Jack de Nijs for Anefo. Creative Commons.

Mary was a pioneering counter-culture rebel and decades before being one was the zeitgeist.

She wanted to go to fashion school. Her parents wanted her to become a teacher.

The compromise was enrolling on the art teaching diploma course at Goldsmiths’ College Art School.

Mary never had any intention of being a teacher. The tensions and rows at home predicted the intergenerational discord of the 1950s and 60s.

Mary explained why her parents’ implacable resistance to her dreams of going to fashion school proved to be an advantage in the end:

‘There is no future in fashion, they said, and from their perspective they were probably right. There was no future in the old ways, fashion came direct from the top couturiers of Paris, and was produced in cheap copies by mass manufacturers for everyone else. Dior’s ultra-luxurious and opulent New Look, for instance, was developed out of a longing for past ideas of female beauty and a desire to sell more fabric – Dior being owned, directed and backed by the millionaire cotton manufacturer Marcel Boussac. The look was so impossibly extravagant and unwieldy for everyday street life that it probably helped hasten the demise of the domination of Paris couture. If I had gone to a fashion school at that time I would have been taken to Paris to see the collections and taught to adapt them for mass production, as that was the way things were done. Luckily I wasn’t. But I longed to design clothes. My parents and I settled on a compromise. I enrolled at Goldsmiths.’

Read More »