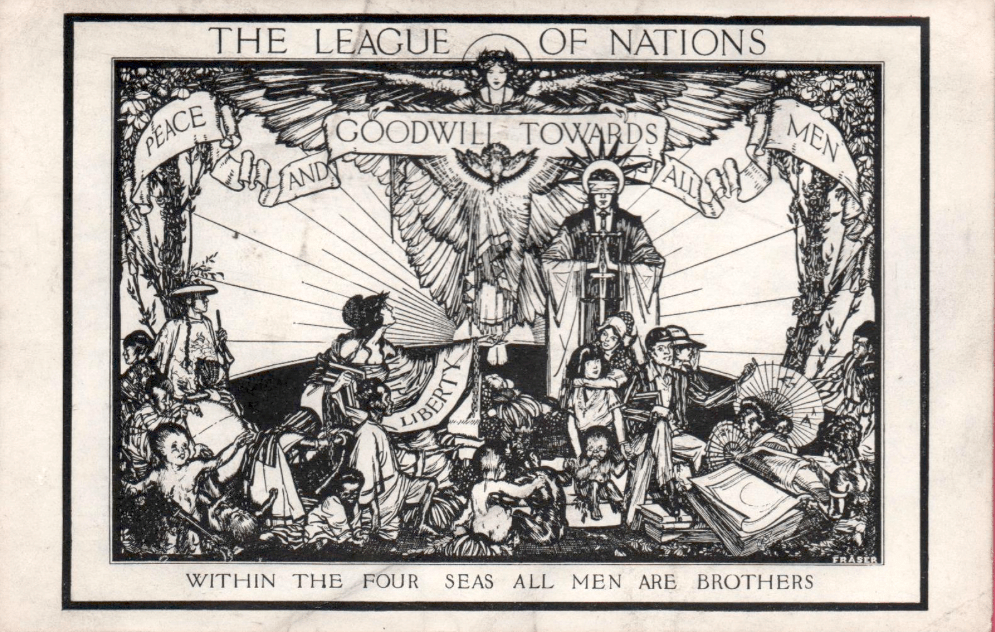

Christmas postcard designed by Goldsmiths Art School student Eric Fraser celebrating the purpose of the League of Nations in circa 1924. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London Archives.

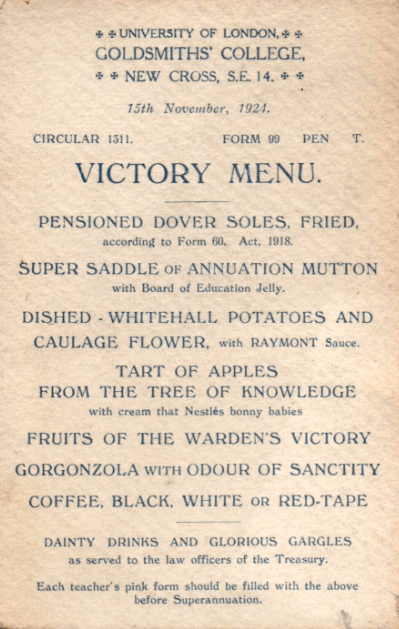

When Goldsmiths’ College decided to host a Victory Dinner in 1924 as an act of remembrance for the Great War of 1914-18, those who had lived through it embraced the occasion with gentle satire.

The Victory Menu for 15th November, four days after Armistice Day, was designed to mock the forms and documents that had been turning education in the post war period into a bureaucracy.

It became ‘Circular 1311’, and ‘Form 99 Pen T.’

Victory Menu for dinner at Goldsmiths 15th November 1924. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London Archives.

There was choice of the main dish: ‘Pensioned Dover Soles, Fried- according to Form 60, Act 1918,’ or ‘Super Saddle of Annuation Mutton with Board of Education Jelly.’

For a side order, the following was on offer and something of a limited choice: ‘Dished – Whitehall Potatoes and Caulage Flower with Raymont sauce.’

The reference to ‘Raymont’ was the name of the second Warden of the college Professor Tommy Raymont.

For dessert, another choice on the menu:

‘Tart of Apples, From the Tree of Knowledge with cream that Nestlés bonny babies

Fruits of the Warden’s Victory

Gorgonzola with Odour of Sanctity

Coffee, Black, White or Red-Tape’

The menu is tailed off with ‘Dainty Drinks and Glorious Gargles as served to the law officers of the Treasury. Each teacher’s pink form should be filled with the above before Superannuation.’

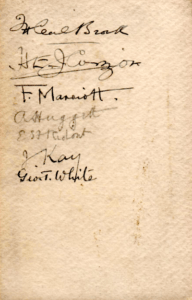

It is the signatures on the other side of the menu that makes this event rather resonant and poignant.

The autographs are by ‘lost to history’ figures in the story of Goldsmiths: F H Cecil Brock, Harry E. J. Curzon, Frederick Marriott, Arthur H R Huggett, Edwin S F Ridout, Joseph Kay, and Graham T. White.

Is it possible that this is a group of Goldsmiths’ College staff tutors who were sitting on the same table and one of them decided their menu card should be signed by their companions?

So who were these people dining in a somewhat ironic celebration of post Great War bureaucracy?

F H Cecil Brock was the Vice-Principal for men in the ‘Training Department’- the largest body within the college teaching teachers to teach. He left to take up the principalship of Crewe College in December 1929, having been a Goldsmiths’ Vice-Principal for nine years.

Harry Edward James Curzon was head of Mathematics from September 1906 to his tragic death from suicide in 1935. He gave nearly thirty years of his life to the College, gained a PhD while lecturing in New Cross in 1920 and was one of the country’s leading educational text book authors on Maths.

At the time of this dinner he was on a salary of £600 a year and, on the basis of his multiple degrees, a BA and MA from the University of Cambridge, a BSc, MA and DSc from the University of London, he was probably the most academically qualified of all the lecturers at Goldsmiths College during this time.

£600 a year in 1924 is the equivalent of £34,500 in 2019.

Frederick Marriott was the oldest of the group at the age of 64 and only a year away from retirement having been the headmaster of the Art School since 1891.

In his time at New Cross he bridged the Victorian age, the Edwardian epoch, Art Nouveau, the First World War, and the beginning of Art Deco.

Like all of the Art lecturers throughout most of the 20th century, his salary was substantially less than his Training Department colleagues.

And for some bizarre reason of hierarchy, the Art School tutors also had to sit in the College refectory on benches that were lower than those of the other members of staff.

Perhaps on the occasion of the Victory Dinner, his seniority and the fact he was a year away from his own superannuation, meant he may have been permitted to dine ‘at the same level.’

He was one of two people at the table who had been working in the New Cross Building when it was the Goldsmiths’ Company’s Technical and Recreative Institute. He had devoted 34 years of his working life to teaching art at Goldsmiths.

Arthur Henry Richard Huggett joined Goldsmiths in the summer of 1906 having just gained his BSc degree from King’s College, University of London. He was appointed lecturer in Nature Study and Drawing and had been trained as a teacher at the famous St Mark’s College in Chelsea.

Two more autographs were supplied by another couple of ‘old timers.’

Graham T.White had been teaching engineering as far back as 1893 in the days of the Goldsmiths’ Institute. He was made head of the Mechanical, Electrical and Constructional Engineering Department in 1919.

Joseph Kay, a lecturer in Teaching and specialising in Manual Instruction and Mathematics, joined at the beginning of the University of London, Goldsmiths’ College reincarnation in September 1905.

Mr Kay would remember looking around the old Royal Naval School chapel that had been utilised as the College’s largest lecture hall when he arrived in September 1905 to prepare for the first term of teaching:

“The Tower of this building housed a staircase, out of bounds in my time. On the plaster ceiling at its head were the naval boys’ inscriptions of earlier Naval students, one of whom I remember, was Lord Charles Beresford.”

He actually earned £25 a year more than Dr. Curzon in 1924, perhaps because he assisted the Vice-Principal for men in organising subjects and leading the teaching of theory and practice and what was described as ‘men’s manual work.’

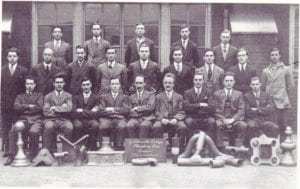

Plumbing class at Goldsmiths’ College 1926-27. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London Archives.

Graham T. White headed an engineering department that started optimistically each year with an enrolment of about 850 students; some of whom studied plumbing. By Christmas drop-outs usually reduced the figure by three hundred.

Mr White specialised in running evening instruction in Mathematics and Physics up to University of London B.Sc standard during Institute days and afterwards.

In 1931 he would take his department away from the College main building in New Cross to become part of the new South-East London Technical Institute half a mile down the road in Lewisham.

Mr J. Kay would retire at the end of August 1931 and A.H.R. Huggett in 1930. Lecturer in History, Edwin Stanley Forsyth Ridout was ‘a new boy’- starting in September 1921. Before taking up his lectureship he had gained degrees in Dublin, Cambridge, London and Lille in France. After 29 years at Goldsmiths, he took retirement in the summer of 1950.

The first college history, The Forge, published in 1955, observed that ‘…the accession of Dr. Ridout to the staff in 1921 greatly helped in levelling up the teams and in establishing the college in University sports during the 1920’s.’

The spirit of the Victory Dinner was not to gloat and glorify the victorious vanquishing of Germany.

At Goldsmiths’ College there was enthusiasm for the first international experiment in creating a global policing body with the purpose of ending all wars.

In the inter-war years between 1918 and 1939, the League of Nations based in Geneva would try to do just that, though historians and people experiencing the agonies of the Second World War argue that it failed to achieve this laudable aim.

Opening of the first session of the League of Nations in 1920. Image: National Library of Norway Public Domain.

And the staff and students at Goldsmiths were so committed to the values of ‘Peace and goodwill towards all men’ and ‘Within the four seas all men are brothers’ that during the 1920s and 1930s the College’s League of Nations Union would enthusiastically organise talks and lectures exploring the tensions surrounding conflict resolution or the lack of it all over the world.

During the session 1934-35, the College’s League of Nations Union played an active part in College life, in spite of a small actual membership of 40.

In that year the Society secured ‘first class speakers’ for its meetings including Dr. Gooch and Dr. Nikolas Hans Ex-Minister of Education for the Kerensky and Bolshevik Governments.

The League of Nations Christmas card for 1924 shown at the top of this article was designed by Goldsmiths School of Art student Eric Fraser who would go on to become one of the country’s leading illustrators of his time.

Perhaps it was exchanged by the men eating their ‘gorgonzola with the odour of sanctity’ in November of that year?

Frederick Marriott, as head of Art, may well have been the person distributing it.

He may well have been sipping his ‘red-tape’ coffee with pride and enthusiasm for his young scholarship winning student whose impressive artwork exhorted the global defence of liberty and depicted children of all races as being the worthy recipients of such freedom and privilege.

For many decades henceforth Eric Fraser would define and characterise much of the design and symbolic representation of sound programmes in the BBC’s Radio Times magazine.

In the years ahead the League of Nations would be a forum for hope rather than an effective resort to justice; where reality would defeat idealism time after time.

In the summer of 1938 students at Goldsmiths’ College concerned about international affairs would have been horrified by the invasion of Abyssinia by Fascist Italy, the invasion of Manchuria and China by a militarised Japan.

Their studies would be pursued against the backdrop of the escalating civil war in Spain, the absorption of Austria into a Greater Germany and increasing tension that would later on that year produce the ambiguity of the Munich agreement.

The independence and security of Czechoslovakia would be violated for the false hope of avoiding war with Germany.

A student signed only by the initials I.M.R. wrote this ‘call to participate in the League of Nations Union’ in the summer edition of the student magazine Smiths:

“Of the three types of person at present inhabiting Goldsmiths’ College, the Communist is noisy, the Pacifist has too little to say, and the Person of no particular opinion seems to offer the only hope of progress. People of the latter sort are so buffeted and bewildered that at the moment they dare not attempt to think for themselves. Yet they can be “mind shakers, moulders of a new world,” since having so far held aloof from any set political belief, they are capable of critical, unbiased judgment.

Yet I would say to them, “Beware of waiting too long.”

Much would be achieved if we could only persuade people to think international before it is too late. The League of Nations, which was formed in this hope, has failed through the lack of faith and goodwill of its members. But that is no reason for deserting it. Rather by joining the Union we should show our desire for better understanding, and help to remedy the League’s weaknesses. It seems a pity that from this College only four students should be sufficiently enthusiastic to attend the exchanging ideas with students from the British colonies and from the United States. Here, at any rate is one chance of showing interest in the world as a whole, and of broadening knowledge.”

Image: By Martin Grandjean – Strictly based on a flag kept by the League of Nations Archives (United Nations Geneva)., CC BY-SA 4.0

For all of the disillusioning disappointments of international affairs during the 1920s and 30s, the League of Nations did at least provide an experience of what was lacking in a worldwide body set up to prevent conflict.

After the horrors of the Second World War, The United Nations was established in 1945 to learn and benefit from the League’s failures.

A key difference would be direct participation, support and involvement of the United States.

And it could be argued that the words of the student ‘I.M.R.’ in 1938 to aim to be among the ‘mind shakers’ and ‘moulders of a new world’ have endured and persisted as an abiding spirit of humanitarian aspiration at Goldsmiths’ College.

That’s So Goldsmiths– a forthcoming history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.