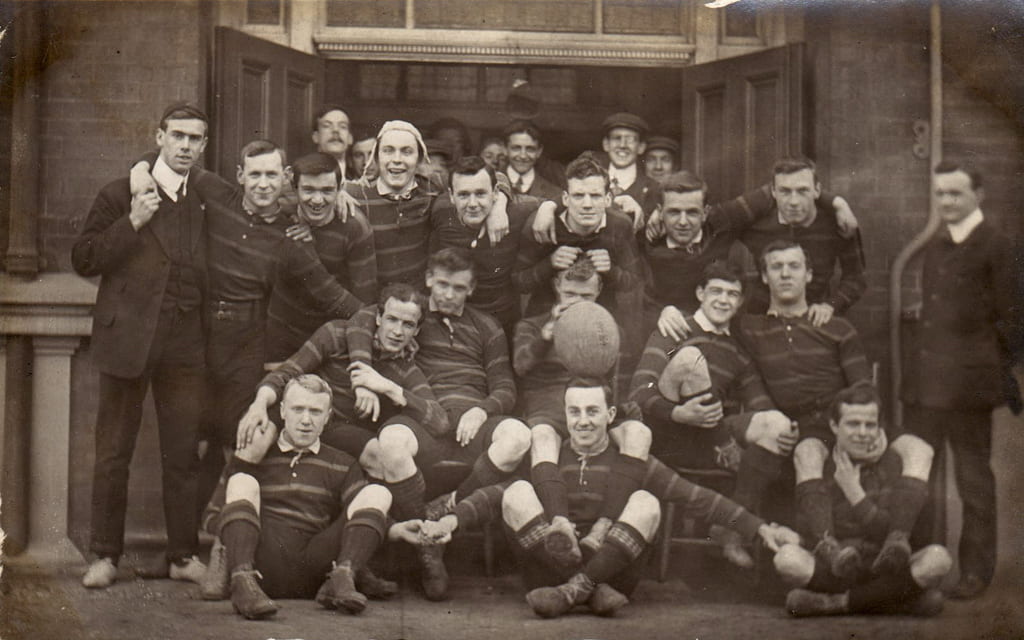

These male seniors of 1908 were labelled ‘The Not Innocents.’ We have no information about why they earned this nickname. Image: Goldsmiths College archives.

Is there a spirit connected with being a Goldsmiths’ student that is somewhat distinctive, radical, questioning, and protesting?

Beyond any desire to ‘brand’ and make distinctive something about Goldsmiths, it is a question with no easy answer.

It might be foolish to generalise. In the photograph above these are men behaving badly for a brief moment: sticking their tongues out, pulling rude faces, making somewhat impolite gestures with their hands, and in one case smoking a cigarette and pipe at the same time.

But there are events and evidence of a tradition that could suggest something.

The Warden, Ross Chesterman (1953-74) recalled deciding to ring up the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Robert Mark, in the late 1960s when some of ‘our students occasionally got into mild trouble with the police, usually because of demonstrations.’

Mark had a fearsome reputation. The local police commander was certainly in fear of him: ‘When the Commissioner Mr Mark says jump, you don’t think about it or argue, you bloody well jump!’

Ross recalled:

“I told him that most of my students were law-abiding and moreover interested in helping others less well-off than themselves. Our talking, conducted at a pleasant conversational level, went on for more than half an hour and I like to feel that I may have helped a little to liberalise the police force.”

The senior men students of Goldsmiths’ College in 1908. They were known as the ‘the Dears!’ We have no idea why they earned this nickname; particularly when there are at least two pairs of the young men actually, or pretending to beat each other up while the photograph is being taken. Image: Goldsmiths College Archive.

One wonders whether one of Ross Chesterman’s predecessor Wardens, Tommy Raymont, had a similar chat with the then Commissioner when Goldsmiths’ students were arrested for being somewhat over-boisterous with the College’s donkey outside New Cross Gate station in 1926.

There had been a procession of one hundred Goldsmiths’ students ‘led by a young man in particularly wide Oxford bags and wearing a long black coat’ which surrounded police officers on traffic duty with the chant of ‘ring-a-ring-of-roses.’

This was accompanied by the loud and aggressive rattling of collection tins.

The College donkey played a major part in the procession straddled ‘by a weirdly dressed figure’ quite possibly one of the students.

Goldsmiths’ College rag students were the Millwall soccer supporters of the university rag world.

The local community lived in fear of impromptu false imprisonment on Lewisham Way or the New Cross Road during rag week.

The College’s first history, The Forge, recorded the origin of the donkey:

“It was on the ostensible ground of economy that in May 1920, a donkey was purchased to replace a horse for the roller on the playing field.”

The notoriety of the Goldsmiths’ rags continued until 1930.

How the College donkey of 1920 to 1930 may have looked. Much loved by the students and used as a mascot in raucous student ‘rag’ stunts to raise money for charity. Image: Tim Crook.

The third Warden, Arthur Edis Dean, decided enough was enough when an entire tram of passengers had been captured by a ring of students outside the College main building while the College song was being sung at morning assembly.

The incident was followed by the students bursting into the Great hall with their ill-gotten gains and the over-excited donkey during the National Anthem.

Warden Ross Chesterman’s philosophy was conveyed to the College’s freshers in the Great Hall in October 1966 with the exhortation:

“Students should divide their time into three segments: one third should be spent working, one third should be spent sleeping, and one third spent enjoying yourself.”

An examination of the College’s picture archives has plenty of evidence that one third enjoyment is something that has been taken to heart rather enthusiastically throughout the generations.

When the college had its own swimming pool, and before it was burnt down by Second World War Luftwaffe bombing, these members of the College Water Polo team certainly showed every sign of enjoying themselves.

But I do wonder if their group hug was a way of dealing with the damp cold of a Deptford winter.

They do look a bit desperate.

It can’t have been much fun walking barefoot on that stone grit scattered over the pathway.

The player in swimming costume top right appears to be grimacing rather than smiling, and I do wonder if he was thinking ‘when is this photographer going to press his flash gun so I can get back inside and warm myself against a radiator?’

Goldsmiths College Water Polo team 1911. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

When you next walk through the corridor entrance of the Richard Hoggart main building just imagine the shenanigans of the College rugby team ‘messing about’ during this photo-shoot in 1910.

In this picture consider all the characters, attitudes, emotions, feelings and relationships.

The central player balancing the rugby ball on his friend’s head below, with his legs around his friend’s shoulders, and peering over the tip of his fingers so only his squinting eyes and forehead can be seen. And then there’s the player leaning forward over the top of his head and scrunching onto his hair as if he were holding onto a pair of goat’s horns!

Goldsmiths’ College rugby first XV of 1910. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

So far it’s been all men looking naughty and mischievous.

Well the women during this time had their own way of showing how smart and quick of wit they were.

The ‘Swanky Swotters’ of 1910 you would not want to be pitched against in an Edwardian University Challenge, or indeed a pub quiz game at the Rosemary Branch or Marquis of Granby.

Group of women students at Goldsmiths’ College in 1910 who called themselves the ‘Swanky Swotters.’ Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

And as for dancing, you do get the impression that these Eurythmics during the time of King George V could jive and boogie off the dance floor any rapper or disco break-dancer of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Eurythmics dance class at Goldsmiths’s College circa 1916-18. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

By 1916-18, Eurythmics were central to the curriculum. The College was dealing with the darker times of the Great War. Women students dominated the student cohort and were coming to terms with continual reports of student and staff casualties from the Front.

It is understood Goldsmiths’ was one of the first British colleges to pioneer this expressive movement art which became quite popular during the early part of the 20th century. It was primarily a performance art, and students were encouraged to develop a movement repertoire relating to the sounds and rhythms of speech, to the tones and rhythms of music, and to ‘soul experiences’, such as joy and sorrow.

Goldsmiths’ Eurythmics of 1916-18. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives. Note the fair amount of photo-bombing faces of people peering through the windows.

Rest assured Goldsmiths’ women students knew their steps and moves, and were ready for anything as this photograph of a physical education class from 1907 undoubtedly confirms.

Women students in physical education in the College gymnasium in 1907. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

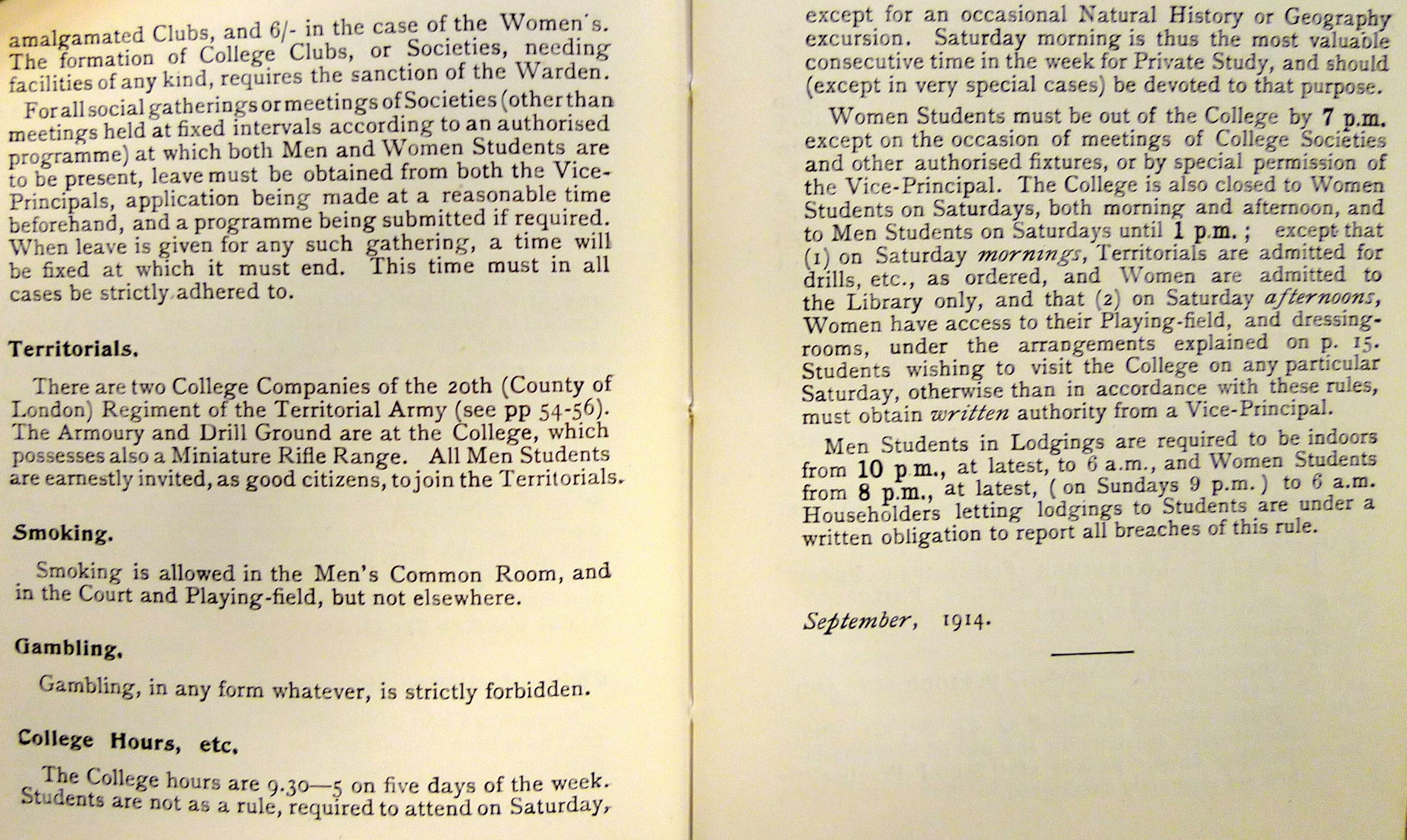

It is not generally known that up until the early 1930s, Goldsmiths’ College students were issued with a student handbook in which they were instructed on rules of gender segregation and strict behavioural standards.

Student handbook for 1914-15. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

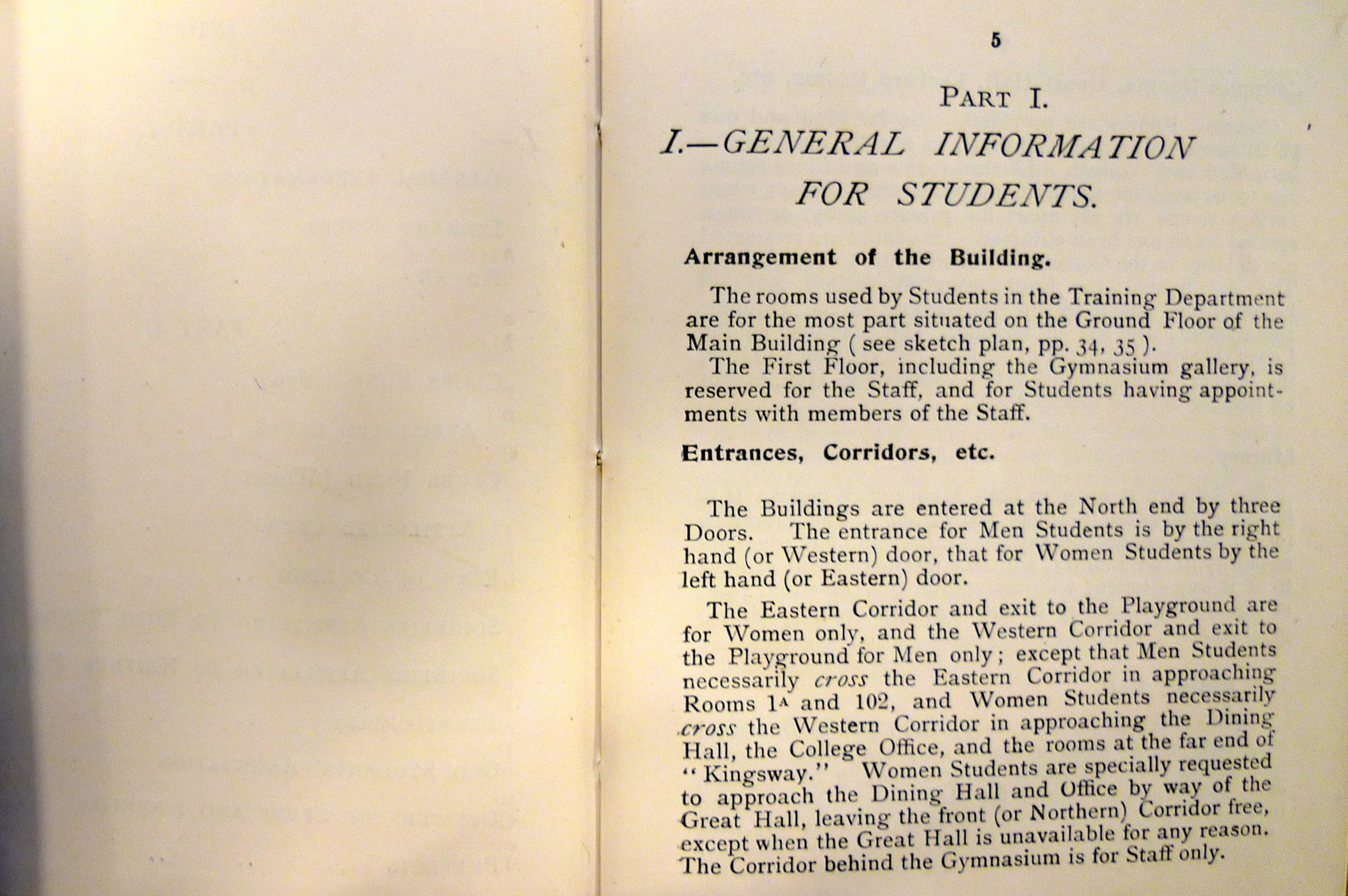

To begin with the first floor was out of bounds. It was exclusively reserved for the staff, apart from the gymnasium gallery- what is now the part of the first floor of the refectory.

Men could only use the western corridor and women could only use the eastern corridor. Yes, they had separate entrances.

Men and women even dined at different times. Women had the first luncheon at 12.15, and the men with two sittings afterwards. For some reason the rulebook states categorically that ‘Women students may not absent themselves from dinner without permission.’

No such stricture applies to the men.

Men had priority over the main lower playing field for cricket and soccer. Women had the upper and smaller playing field. Each had different pavilions. The men’s was bigger. Neither could be seen using each other’s.

The men and women students had separate common rooms. Men could smoke in their common room.

Nothing was said about whether women could smoke in theirs. So perhaps they did!

The enforcers were a cadre of awesome looking Goldsmiths’ students recruited as prefects.

Consider this delightful selection of rule enforcers for the academic year 1908-9.

Goldsmiths’ College prefects 1908-9. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

The young woman sitting far left in the front row has a very disapproving face. You can almost hear her saying: ‘Crook, not you again!’

The young man standing far right does not look like he has much tolerance for slackness and lack of discipline. Such an attitude appears to be held by his compatriot standing bold and upright on the other side holding his hands behind his back.

And the young woman sitting far right might be wearing an expression of grave disappointment in the human race.

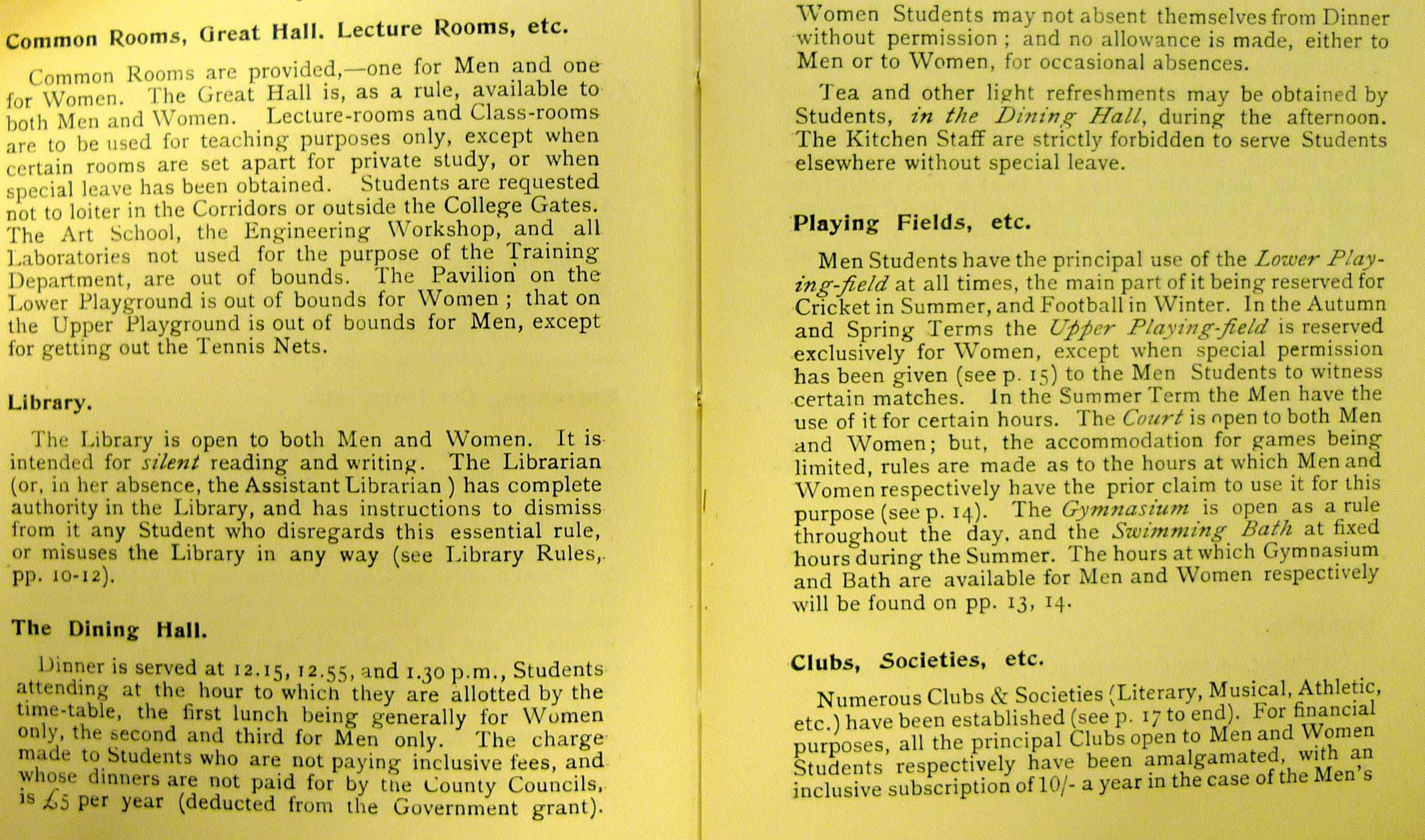

There was more discrimination in the ‘in bed’ and ‘lights out’ rules.

Men had to be in their hostels by 10 p.m., but for some reason women had to be confined two hours earlier at 8 p.m.

Landladies and landlords of private lodgings were contractually obliged to report the comings and goings of Goldsmiths’ students according to this timetable. And no early morning jaunts before 6 a.m. though it seemed to be accepted that there did not appear to be any need for gender differentiation for the early morning stricture.

The view from the women’s Upper Playing Field- smaller than the men’s lower playing field which had the bigger pavilion (seen with the clock on the right) and soccer and cricket facilities. The position of the women’s playing field is now occupied by the Professor Stuart Hall Building and tennis courts. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

It has to be said that where there are rules, there are rule-breakers and you do get the impression from this jaunty and riotous image of ‘Dan Leno’s troupe’ from 1909, that the students of yesteryear had their own ways of living and breathing the necessary freedoms to develop as young adults in the early part of the twentieth century, without being caught by the formidable prefects.

Goldsmiths’ College senior men students in 1909 not taking very seriously an occasion for official photography. Image: Goldsmiths’ College Archives.

Rules for Goldsmiths’ students from the Handbook 1914-15

Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

When the College started in the autumn of 1905, the staff recorded their evaluation of the first students in very precise minutes.

The general view was not particularly optimistic. In November the science lecturers reported that their students were: ‘All quite ignorant.’

Miss Strudwick was concerned that: ‘they express themselves badly and are very inaccurate.’

In history the lecturer Miss Spalding despaired: ‘very unintelligent, unable to take proper notes, and very ignorant of present conditions.’

There was concern about the students’ lack of punctuality which was not helped by the College clocks showing different times.

It was suggested that lecturers ‘close doors occasionally and reckon all excluded students as late.’

On the subject of homework, the students were complaining of being over-worked.

The minutes state: ‘The Vice-Principals think there is overwork in the case of the more stupid students.’

Pages 6-7

Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

There is not much evidence of punishment and sanctions being applied to Goldsmiths students in the early decades of the College’s existence.

It is possible that any documents relating to most disciplinary processes may well have been destroyed.

But just occasionally it is possible to identify traces of action being taken to terminate a student’s participation.

For example, Goldsmiths’ College Delegacy minutes for the University of London disclose that in 1923-4, ‘Two men students have been dismissed in consequences of grave misdemeanour since the opening of the session. One woman student returned in January to complete her interrupted course.’

In December 1924 there is a very sad record of the College reporting that a trainee teacher had to be dismissed after suffering ‘seizures’ while at the college.

The indication is that the student concerned was epileptic.

It transpired that when the college’s medical officer checked with his general practitioner, the student had concealed his condition when applying for a grant.

It was a reflection of the prejudiced values of the time that the minutes declare he: ‘…was not, therefore, a suitable person to be trained as a teacher.’

Those records that have survived ask many more questions than they answer about students whose unusual lifestyle did not necessarily conform to the norms of the time.

Certainly more research is going to be undertaken in respect of a named student whose dismissal was recorded in February 1922:

“The Warden stated that an ex-service student of the training department had been under suspicion of leading an irregular mode of life for some time; that after this was proved to be the case, and after having obtained the sanction of the Board of Education, he had dismissed him, acting on behalf of the delegacy, on the ground that he was not a proper person to be enrolled as a certificated teacher.”

In 2018 we want to know what was meant by ‘irregular mode of life’ in 1922, what was the nature of the ‘suspicion’ and whether it were possible to find out how the student had been judged as ‘not a proper person’ to be working as a teacher.

Pages 8-9

Image: Goldsmiths College Archives.

That’s So Goldsmiths– a forthcoming history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.