Dame Mary Quant has been hailed as the fashion genius who changed the way people thought, felt and looked in Britain.

After her passing at the age of 93 on 13th April 2023 she featured on at least 10 of the front pages of the UK’s national newspapers with tributes such as the ‘Designer who revolutionised British fashion in the 1960s’, and ‘The 60s high street fashion trailblazer’ who ‘blew the doors off fashion as we knew it.’

The headlines reflected her iconic status: ‘Farewell, Ms Miniskirt’ (Metro), ‘Pioneer of mini-skirt who shaped Sixties’ (Express), ‘Visionary British youth culture pioneer and 1960s fashion icon’ (Financial Times), ‘Fashion owes so much to her” (Guardian), ‘Farewell to the queen of fashion’ (i newspaper), ‘The genius who invented modern fashion’ (Mail), ‘Revolutionary Quant’ (Scotsman), ‘Mini skirt queen Mary’ (Star), ‘Farewell, contrary Mary’ (Telegraph), ‘fashion designer who popularised the miniskirt and created a liberated look for young women that defined the Swinging Sixties’ (Times).

In her two autobiographies, Quant by Quant, first published in 1966, and Mary Quant Autobiography, published in 2012, she started with her time at Goldsmiths and the years she pursued her passion for art and design in The Goldsmiths’ College Art School of that time.

She celebrated her dramatic and stylish first encounter at a Goldsmiths Christmas Arts Ball with her first husband and partner, the aristocrat Alexander Plunket Greene and she relished talking about the influence and experiences with the avant-garde world that Goldsmiths opened up for her.

She was taught by leading modernists and surrealist artists, designers and illustrators such as Sam Rabin, Betty Swanwick and the legendary embroiderer and textile artist Constance Howard.

She was surrounded by fellow disruptors and cultural subversives- the notorious art forger, Tom Keating, who dedicated his talent and painting career to expose the capitalist greed of the art world, and Quentin Crisp ‘The Naked Civil Servant’- writer, illustrator, actor, and artist’s model. The celebrated abstract artist and designer Bridget Riley was another contemporary student.

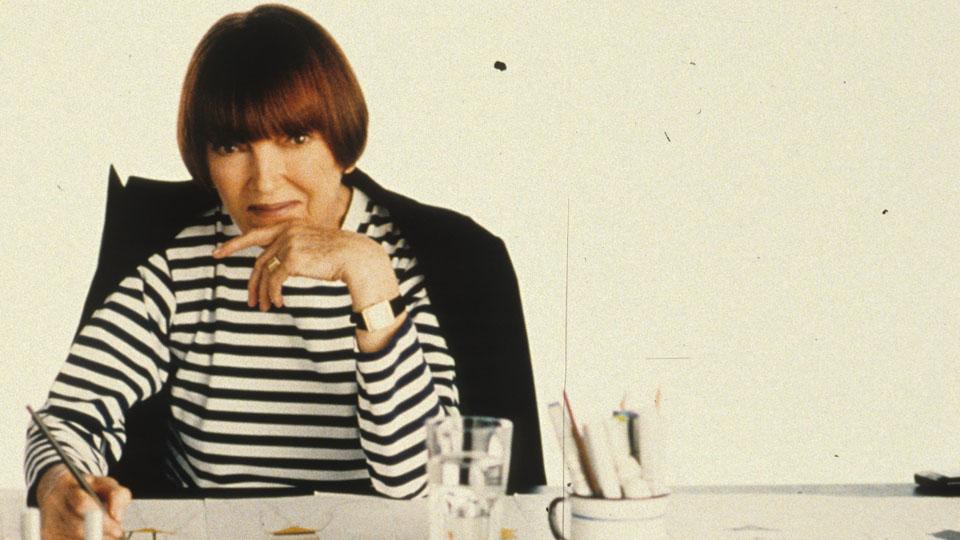

Mary Quant would always remain a friend to Goldsmiths. On 23rd September 1993, she returned to receive an Honorary Fellowship and her advice thirty years ago to the graduating students in the Great Hall of the Richard Hoggart main building remains prescient in the present day.

She predicted the impact and significance of ‘the knowledge explosion’- which is now the digital information age of artificial intelligence, the implications of people living longer, and the need to be flexible and seize the opportunities of the future.

Mary was born Barbara Mary Quant in Blackheath in 1930 to high achieving parents, Jack and Mildred from tough working class backgrounds in Wales. They both gained firsts at university and became teachers- her mother actually lectured at the London College of Fashion.

Her family evacuated to the Kent countryside during the Second World War where she witnessed the Battle of Britain in the summer of 1940.

Mary Quant in 1966. Jack de Nijs for Anefo. Creative Commons.

Mary was a pioneering counter-culture rebel and decades before being one was the zeitgeist.

She wanted to go to fashion school. Her parents wanted her to become a teacher.

The compromise was enrolling on the art teaching diploma course at Goldsmiths’ College Art School.

Mary never had any intention of being a teacher. The tensions and rows at home predicted the intergenerational discord of the 1950s and 60s.

Mary explained why her parents’ implacable resistance to her dreams of going to fashion school proved to be an advantage in the end:

‘There is no future in fashion, they said, and from their perspective they were probably right. There was no future in the old ways, fashion came direct from the top couturiers of Paris, and was produced in cheap copies by mass manufacturers for everyone else. Dior’s ultra-luxurious and opulent New Look, for instance, was developed out of a longing for past ideas of female beauty and a desire to sell more fabric – Dior being owned, directed and backed by the millionaire cotton manufacturer Marcel Boussac. The look was so impossibly extravagant and unwieldy for everyday street life that it probably helped hasten the demise of the domination of Paris couture. If I had gone to a fashion school at that time I would have been taken to Paris to see the collections and taught to adapt them for mass production, as that was the way things were done. Luckily I wasn’t. But I longed to design clothes. My parents and I settled on a compromise. I enrolled at Goldsmiths.’

The world of Goldsmiths’ College Art school that Mary Quant entered in 1950 is evoked in this Pathé news film covering the ‘Students rag’- an annual carnivalesque charity fundraising activity.

The theme for the rag that year was bullfighting:

Mary Quant began her 1966 autobiography with the arresting panache and style of her fashion designing:

‘Life as I know it now began for me when I first saw Plunket.

I had to wait three months before he noticed me and during that time I just watched from the outskirts of a posse of disciples who surrounded him constantly, hanging on his words, rushing about to fetch and carry for him and generally imitating his style.

I had been at the Goldsmiths’ College in south-east London for a few months when Plunket turned up, ostensibly to study illustration although I should think the records of his attendance at classes must be unique because he never seemed to make an appearance until late in the afternoon.

Apparently he used Goldsmiths’ as a club and it was only when he was pushed and had nothing better to do that he turned up at all. So long as he dropped in and continued to be registered as a student, his mother gave him an allowance.’

Mary would later describe the typically Goldsmiths burlesque circumstances when she and her future partner and husband Alexander Plunket Greene connected:

‘I never found the courage to speak to him and it wasn’t until the Christmas Ball, a fancy dress affair rather like a smaller and more parochial version of the old Chelsea Arts Ball, at the end of his first term at Goldsmiths’ that he noticed me.

Because I was small, I had been stuck on top of a pile of balloons and, at midnight, practically naked, perched in the middle of hundreds of them, I was dragged round a dance floor on a float. I clutched an enormous bunch of balloons round my middle to disguise as much of myself as I could as I was rather fat.

‘Mary Quant Among Balloons. Sixteen year-old Goldsmiths’ College student and future fashion designer, Mary Quant, helping with preparations for the Chelsea Arts Ball at the Royal Albert Hall, London, 30th December 1949. (Photo by Fred Ramage/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)’

This was the moment when Alexander says he first saw me. But, even then, he didn’t speak. He was having a slightly unsatisfactory evening. He had arrived most immaculately dressed as Oscar Wilde, wearing a superb black frock-coat and carrying a single enormous lily. The trouble was that another student turned up as Lord Alfred Douglas. They were made to dance together all evening.’

Mary would marry ‘Plunket’ in Chelsea in 1957- barely two years after their precarious launching of boutique and restaurant in the King’s Road.

The Goldsmiths’ Art College scene Mary entered in the first years of the 1950s decade was an intensity of experimentation, emerging youth culture chutzpah, and outstanding mentorship and tutoring from leading artists.

On leaving Blackheath High School, Mary had been awarded a scholarship which would have been approved by the ‘Head Master’ of the Art School, the impressionist modernist painter Clive Gardiner who has had a major influence on 20th century artists and designers such as Graham Sutherland who was also a painting tutor at Goldsmiths’ during Mary’s time there as a student.

In 1950 the Art School embroidery lecturer, Constance Howard, was commissioned by F. H. K. Henrion to produce a hanging for the country pavilion of the South Bank exhibition for the Festival of Britain.

The Country Wife hanging for the 1951 Festival of Britain by Constance Howard. Mary Quant worked on the embroidery while a student of Constance’s at Goldsmiths Art School in 1950. It is now accommodated in the WI Collection at The National Needlework Archive in Newbury and undergoing restoration.

The stumpwork narrative hanging, The Country Wife (measuring 18½ ft × 13½ ft), depicted the varied activities of the National Federation of Women’s Institutes (NFWI). Constance designed it and crafted it with the assistance of her students who included the future fashion designer Mary Quant and volunteers from Women’s Institutes around the country.

As Mary would later explain to Goldsmiths in an interview in 2010: ‘You grabbed a table for yourself and put your things there and just got on with your work really – no nonsense with lectures and stuff!’

Another influential art tutor was the modernist painter and sculptor Sam Rabin who had been an Olympic bronze medal winning wrestler in 1928 and starred in Alexander Korda’s films as the champion wrestler in The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) and as the Jewish prize-fighter, Mendoza, in The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934).

In her second autobiography published in 2012 Mary described how the culture of learning art at Goldsmiths was by doing and practice:

‘The staff were all working on their own projects – painting, sculpting, illustrating or appliqué – and it was up to you to elbow them if you wanted attention. But the atmosphere was terrific. There were life-drawing and painting classes going on, but what you chose to participate in was up to you. I think there is a lot to be said for this approach. Box ticking would have been laughed out of the place.

Male students in their twenties, returning from war, were older than anyone alive should ever be, through dint of ghastly experience. Meanwhile the teen generation were thoroughly anarchistic. Life drawing exaggerated this distinction: some of the veterans were so war-damaged that they sat on their benches, called ‘donkeys’, just sharpening their pencils over and over, while other teenage students were producing pornography that they sold in Soho. Quentin Crisp was the most admired model and the most difficult to draw. He knew it and struck crucified poses for us to interpret.’

Quentin Crisp by Ella Guru. GNU Free Documentation License

Quentin Crisp had been a longstanding life model at Goldsmiths Art School famously holding a pose during a V1 doodlebug raid in 1944 and continuing with it even after the students had fled to their air raid shelter.

They returned to find him with his trademark crucifixion posture surrounded by broken glass though mercifully unscathed.

Mary explained that her ideas for fashion came from the clothes and style she and her fellow students at Goldsmiths created for themselves:

‘I knew I wanted to design solely for myself and other students: we were our own market. Most art students dressed like Augustus John models, with dowdy skirts and a deliberately ill-kept look, but my four friends dressed like me. Instead of corsets, we wore wide elastic belts at the waist, called “waspies”, with shorts or peg-top skirts like Mods and Rockers, and slick little pin-tucked tops or tight neat sweaters. Our legs would be covered with knee socks (or bobby sox for the Sinatra fans) or theatrical fishnet tights if you were lucky enough to find a source, and our hair would be tied back in ponytails. Small triangular polka-dot scarves tied sideways, cowboy style, rounded off the look. We devised our own clothes, making semi-circular gingham skirts you could jive in. Fashion became democratised for the first time.

We were Picasso fans. We loved French films and “riverboat shuffles”, adored cheap French food and Paris, but longed to get to America. We dined on trad jazz and the style of New Orleans, and drank in the new forms of modern jazz and rock.

New ways to dance, new ways to dress, new ways to live.’

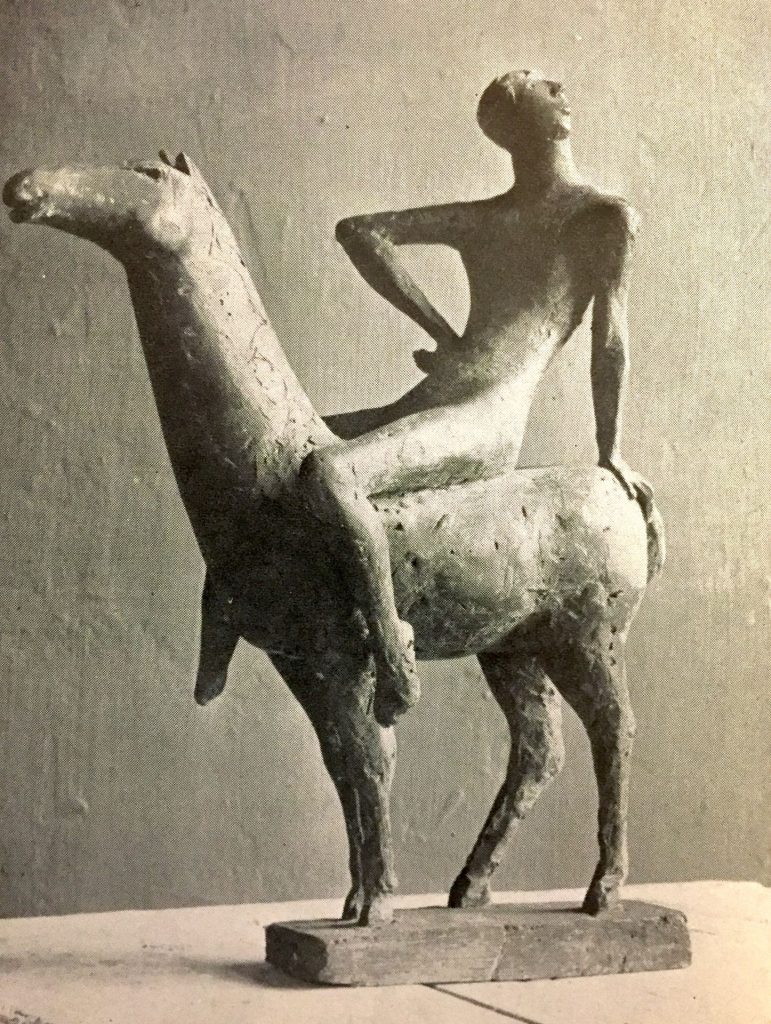

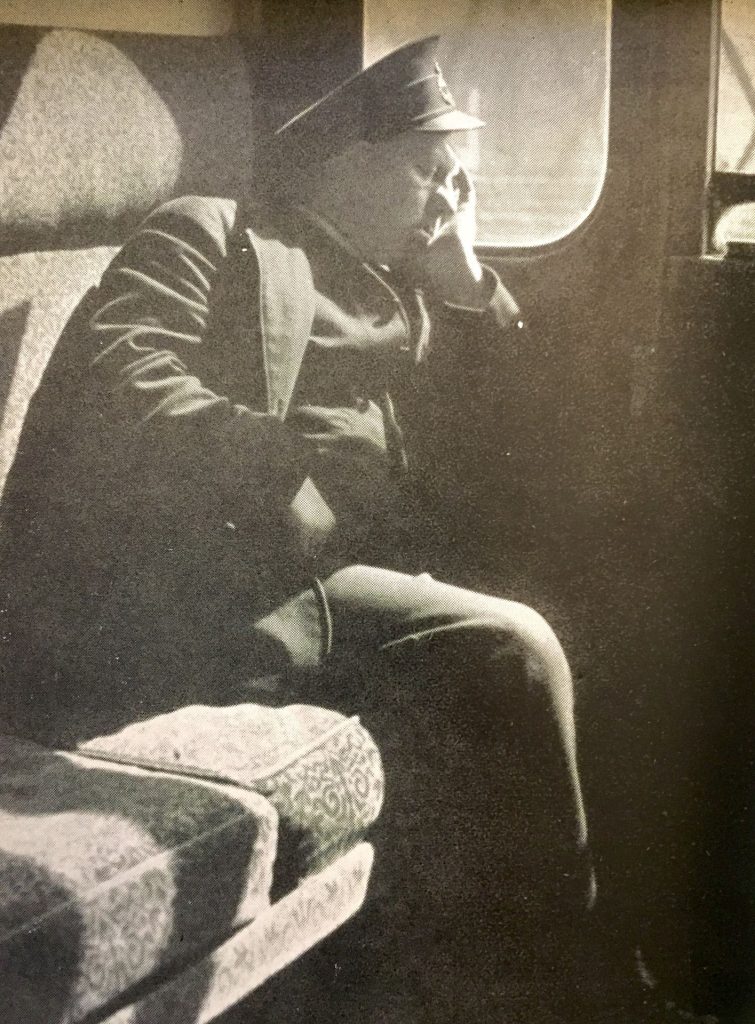

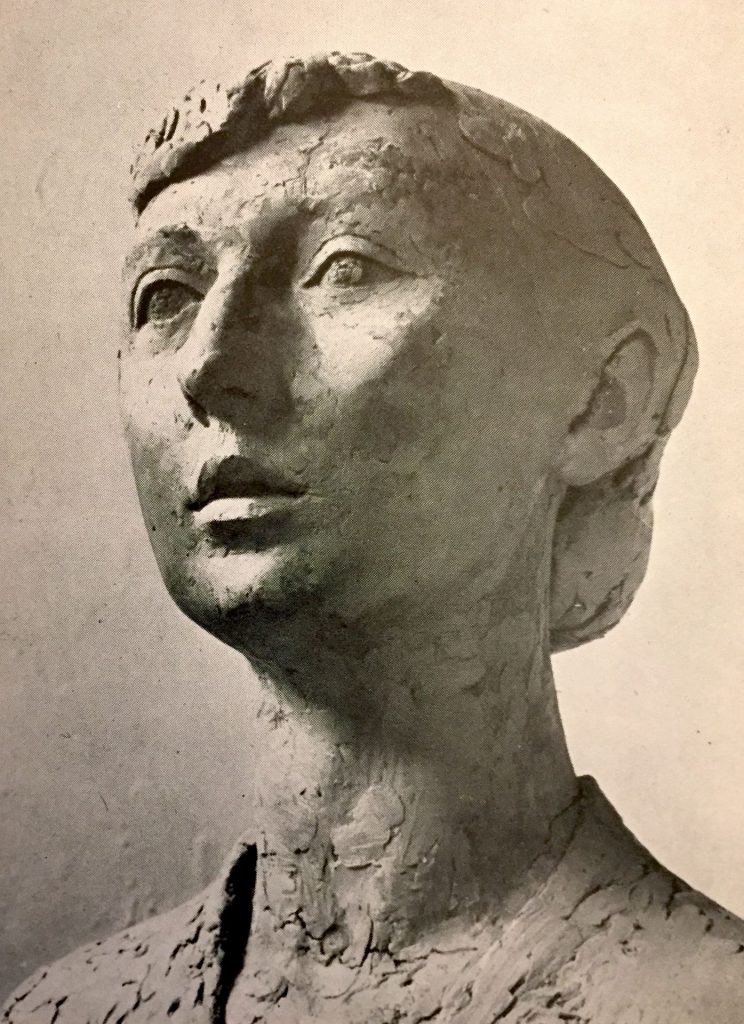

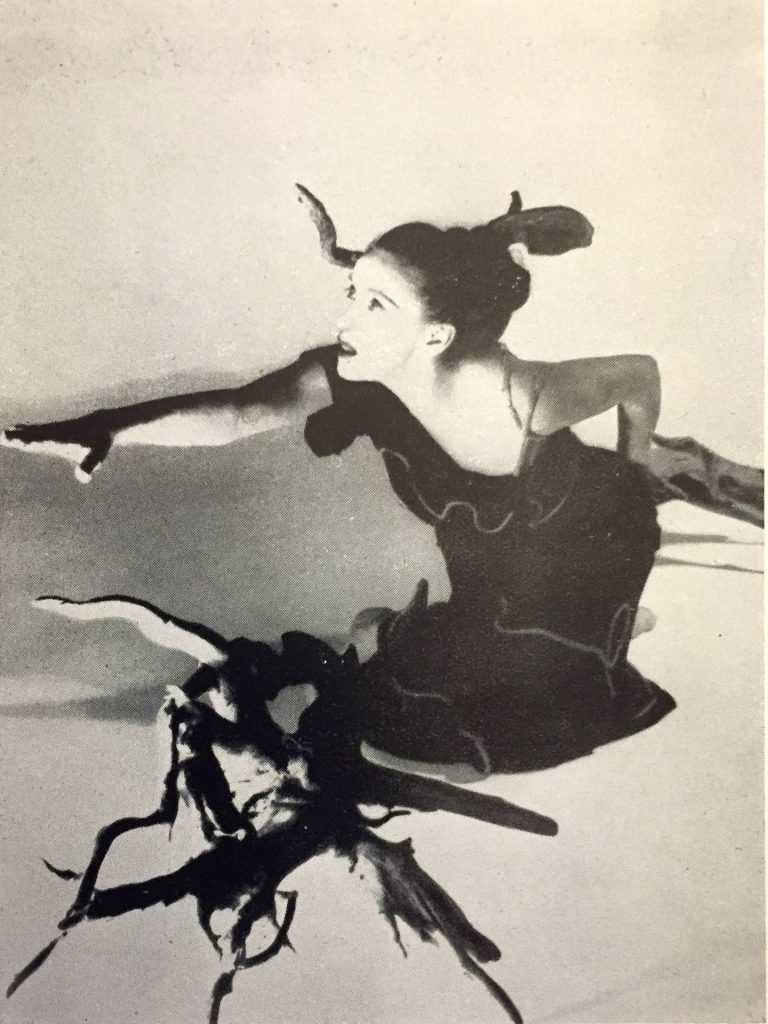

The art produced by her generation of students is featured in Smith Magazine for 1954. Documentary photography by W Harris in the form of a black and white image of a train guard falling asleep in a train carriage called ‘Sleeping Journey’, sculture by G Pullen titled ‘Study of a Girl’, C Young’s ‘Horse and Rider’, and art photography by Bennet and Pleasant described as: ‘Martha Graham in “Cave of the Heart.”‘

S. Tottman wrote a poem called Manifesto:

Let us eat what we are offered

And accept the proffered hand,

Let us go to Church on Sundays,

Build our castles in the sand;

Let us circulate to music,

Let us smile upon the rustic,

Let us keep our minds elastic

Or let us all go mad.

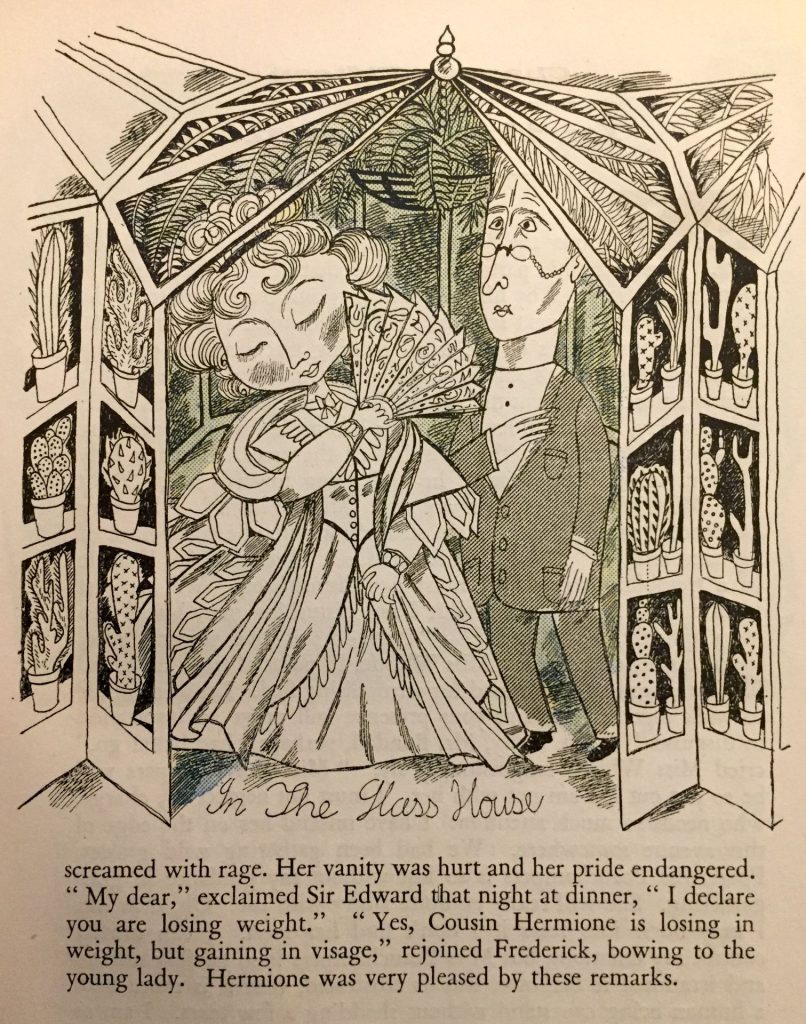

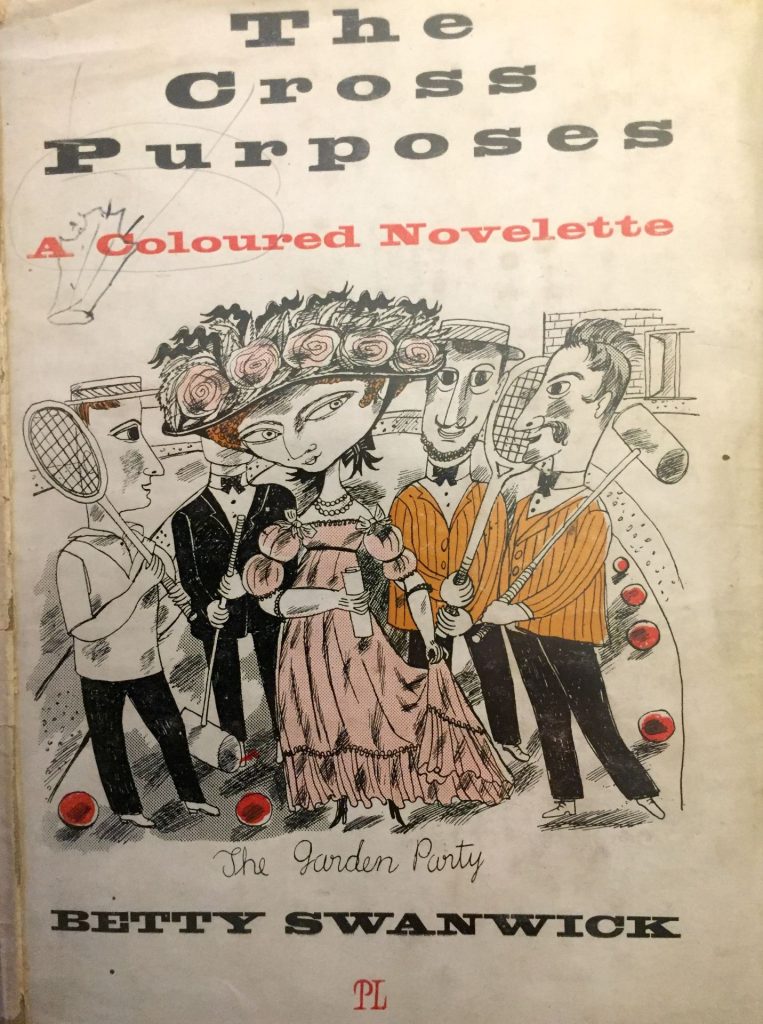

When Alexander Plunket Greene could get up in time for illustration classes Mary and he would be taught by Betty Swanwick- an original surrealist whose illustrated novel The Cross Purposes had been published in 1945. She would later go on to design an album cover Selling England by the Pound for Genesis in 1973.

What is perhaps much less well known about Mary’s time at Goldsmiths is that she was a promising and competitive tennis player:

‘…we were all mad about tennis and I was lucky enough to have a Surrey coach teaching me. Years later I was called in to play with the male team from Goldsmiths Art School, playing the priests’ seminary near Guildford. Nobody told me it was a male affair until I arrived there in the shortest shorts seen by mankind at the time – to rapturous applause from the priests.’

A fascinating Instagram image released in 2016 of a Goldsmiths’ College scarf from the early 1950s damaged by fireworks unfolded the story of Mary’s Goldsmiths doubles partner taking part in demonstrations as told by his great niece Charlotte Downs, who also decided to go to Goldsmiths.

‘This scarf was given to me by my Grandad’s youngest brother, some may recognise it as a @goldsmithsuol college scarf. He wore it during his days studying fine art (around the time of famous alumni Mary Quant, his tennis doubles opponent and close friend). After some venturing around London protesting, as students do, they headed back to the college green to let off fireworks and celebrate.

The hole is a burn mark from a firework that landed in it and went off in his ear, leaving him deaf for at least a week.

Unfortunate timing as he was in mid application to the RAF, permanent deafness would have stopped him in his tracks. Fortunately he recovered, all went well and he achieved what he wanted of being a member of the RAF.

My great uncle passed at this time a few years back but before he did, he gave me this scarf to celebrate his time at Goldsmiths and as a note for me to continue on with my own Goldsmiths’ generated creative endeavours. Uncle John you’ll always be remembered as a remarkable man!’

The leaving of Goldsmiths

Mary Quant had two versions: one gloriously Bohemian and romantic; the other realistic and sobering. We will start with the romantic one which is in fact the beginning of the equally brilliantly written second Mary Quant autobiography:

‘MY FUTURE HUSBAND, Alexander Plunket Greene, was a 6’2″ prototype for Mick Jagger and Paul McCartney rolled into one. He wore his mother’s gold silk pyjamas and burgundy hipster drainpipe pants to Goldsmiths Art School, where I was studying illustration at the time. He had long, silky, jaw-length hair, flopping under one arm. We met at the art school’s fancy dress ball – I was on a float wearing black mesh tights and some balloons. APG said it was lust at first sight. I was simply bowled over.

“Come to Paris” he said. “I am busking outside the George V Hotel.”

It was 1953.’

Now the cold light of day and being plunged into the world of work, having to leave home version from Mary’s first autobiography:

‘I simply had to leave home. As a result of the life I was leading, my relationship with my parents was appalling. But I had absolutely no money and simply couldn’t afford to live anywhere else. I had failed to get the Art Teachers’ Diploma at Goldsmiths’. I knew I had to find a job. In spite of the never-ending rows at home, I was determined I was not going to be a teacher.

Finally, after searching round and making endless inquiries, I got a job in the workroom of Erik, the milliner, in Brook Street. I was paid £2. 10s 0d a week. Out of this I had to pay my fares from Blackheath and buy stockings and that sort of thing. There was never any money for food and I spent nothing on clothes. I made all these myself, sitting up most of the night to remake the same dresses year after year and try to give them something of a new look. Alexander had left Goldsmiths’ too. He had a sort of job as a photographer in the King’s Road.’

Eventually Mary, Alexander and another friend would take over the basement and ground floor of Markham House.

The boutique Bazaar on the ground floor would become the legend in the story of British and indeed world fashion.

The restaurant in the basement below called ‘Alexander’s’ would be the chic place to go for the new generation of actors, writers, film directors and pop groups.

It gained success because the likes of Brigitte Bardot and Audrey Hepburn could dine there knowing there would be no phone calls to Fleet Street.

Mary would later recall: ‘The young actors at the Royal Court Theatre would take our debs out to lunch in the restaurant and buy them clothes in Bazaar afterwards – they were salesmen for us, including John Osborne. It was really only Brasserie Lipp in Paris that had a similar atmosphere.’

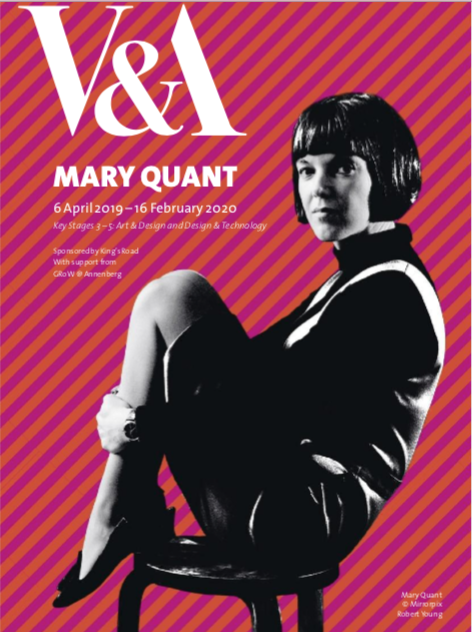

The rest, as is often said, is history and much better related in the recent film documentary about Mary, her V&A exhibition and the many multimedia narratives, and now obituaries published all over the world.

Bazaar eventually became the Markham Pharmacy. Its most recent incarnation is as ‘Joe the Juice’ bar complete with blue plaque explaining the building’s historical significance.

Goldsmiths’ College Art School records for this time are virtually non-existent and it is unclear whether or not Mary graduated and with what. Art students just enrolled and did their courses in those days.

Actually Mary turned out to be rather a good lecturer in fashion, which she was very happy to do when she had any time out from running her global businesses.

And in 1993 Goldsmiths gave her the equivalent of an Honorary PhD with the award of the University’s Honorary Fellowship.

She graciously accepted on the same platform as another distinguished alumni, the Law Lord, Lord Gordon Slynn of Hadley (the equivalent of a current Justice of the UK Supreme Court) who had also been the Advocate General in the European Court of Justice.

On this Thursday 23rd September 1993 hundreds of graduating students and their families heard Mary Quant say:

‘Thank you for making us Fellows of one of the most splendid colleges in the world. As you know we are both former students and so it is with a particular evocative sense of nostalgia and opportunity that I address you.’

Mary said she was grateful to Goldsmiths for being a place where ‘staff and students had both time and space to develop their own potential…it was that environment that encouraged us to think that, “anything was possible.”

And thus it is no surprise that over the years in that atmosphere Goldsmiths’ has produced a spectrum of students ranging from a Home Secretary to the manager of the Sex Pistols. From Graham Sutherland and Bridget Riley to the great faker, Tom Keating, who now gives a new meaning to the second line of the College hymn:- “The Smiths’ are forging on.”

Mary said: ‘The one lesson which I am sure being at Goldsmiths’ has taught you is that you have to be flexible.

I little thought when I designed the mini skirt that in a few years time I would be in cosmetics. I certainly never thought that the bulk of my work would be in Japan.’

Her concluding message to all those assembled was ‘Be flexible, Seize your opportunities.’

Multimedia tributes and resources on the life and achievements of Dame Mary Quant 1930-2023

Professor Emeritus Angela McRobbie looks back at the designer’s work and the huge impact the former Goldsmiths student and Honorary Fellow had on society. ‘How Dame Mary Quant helped changed the world’

See: https://www.gold.ac.uk/news/mary-quant-reflections/

Guardian obituary by Veronica Horwell ‘Dame Mary Quant obituary- Designer who revolutionised British fashion in the 1960s’

See: https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2023/apr/13/dame-mary-quant-obituary

Jess Cartner-Morley in the Guardian: ‘Equal parts practical and daring: how Mary Quant created look for a new way of living’

Swinging 60s icon brought a sense of female liberty to her designs

BBC ‘Dame Mary Quant: Fashion designer dies aged 93’

See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-65265531

BBC Obituary Dame Mary Quant: The 60s high street fashion trailblazer

See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-18151227

Times: ‘Mary Quant blew the doors off fashion as we knew it.’

See: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/mary-quant-blew-the-doors-off-fashion-as-we-knew-it-tkjgnttbq

The Warden, Professor Frances Corner has paid tribute to Dame Mary Quant after the celebrated fashion designer and former Goldsmiths student passed away at the age of 93.

See: https://www.gold.ac.uk/news/dame-mary-quant-tribute/

Goldsmiths Interview and profile https://www.gold.ac.uk/honorands/mary-quant/#d.en.119916

The Times view on the death of Mary Quant: ‘Queen of Cool. The fashion designer was a shrewd and stylish icon of the Swinging Sixties.’

See: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-times-view-on-the-death-of-mary-quant-queen-of-cool-mmfqwpbct

Times obituary: ‘Dame Mary Quant, fashion designer, dies aged 93’

See: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/dame-mary-quant-fashion-designer-dies-aged-93-gnqmpw7ft

New York Times: ‘Mary Quant, British Fashion Revolutionary, Dies at 93’

See: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/13/fashion/mary-quant-dead.html

Telegraph Obituary: ‘Dame Mary Quant, fashion designer who brought the miniskirt to Swinging London’

See: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2023/04/13/mary-quant-obituary/

Washington Post Obituary: ‘Mary Quant, British designer who dressed the swinging ’60s, dies at 93’

See: https://www.washingtonpost.com/obituaries/2023/04/13/mary-quant-miniskirt-designer-dead/

Véronique Hyland in Elle: ‘Mary Quant Liberated More Than Just Our Legs.’

See: https://www.elle.com/fashion/a43591138/mary-quant-obituary/

Daily Express: ‘Dame Mary Quant, fashion designer, 1930-2023 – obituary’

See: https://www.express.co.uk/news/obituaries/1758120/mary-quant-mini-skirt-fashion-sixties

Mary Quant V&A Exhibition in 2020

See: https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/mary-quant

Introducing Mary Quant V&A exhibition

See: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/introducing-mary-quant

‘Mary Quant was born and brought up in Blackheath, London, the daughter of two Welsh schoolteachers. Following her parents’ refusal to let her attend a fashion course, Quant studied illustration at Goldsmiths, where she met her future husband, the aristocrat Alexander Plunket Greene. She graduated in 1953 with a diploma in art education, and began an apprenticeship at a high-end milliner, Erik of Brook Street. In 1955, Plunket Greene purchased Markham House on the King’s Road in Chelsea, London, an area frequented by the ‘Chelsea Set’ – a group of young artists, film directors and socialites interested in exploring new ways of living – and dressing. Quant, Plunket Greene and a friend, lawyer-turned-photographer Archie McNair, opened a restaurant (Alexander’s) in the basement of the new building, and a boutique called Bazaar on the ground floor. The different strengths of each partner contributed to their long term success; while working together on all aspects – Quant concentrated on design, Plunket Greene had the entrepreneurial and marketing skills, and McNair brought legal and business sense to the brand.’

‘Quant was a self-taught designer, attending evening classes on cutting and adjusting mass-market printed patterns to achieve the looks she was after. Once technically proficient, she initiated a hand-to-mouth production cycle: the day’s sales at Bazaar paid for the cloth that was then made up overnight into new stock for the following day. Although exhausting, this cottage-industry approach meant that the rails at Bazaar were continually refreshed with short runs of new designs, satisfying the customers’ hunger for fresh, unique looks at competitive prices.’

Mary Quant – Discovering Fashion – True Story Documentary Channel

Quant – Official UK Trailer (2021) Documentary film. ‘The life and legacy of 1960s fashion icon, Mary Quant’ directed by Sadie Frost. Includes interviews with Kate Moss, Camilla Rutherford, Vivienne Westwood, Edward Enninful, Zandra Rhodes, Orlando Plunket Greene and archive of Mary Quant and Alexander Plunket Greene.

Mary Quant V&A Dundee Working with Mary Quant 2020. Heather Tilbury Phillips, former Director of Mary Quant Limited, worked closely with Mary Quant for over a decade. She spoke to us about her experience of working with Mary, at a time of revolutionary social change.

Farewell, Mary Quant V&A Dundee 2020. 15 Jan 2021

‘Join us for a look around the ‘Mary Quant’ exhibition, narrated by our Curator Kirsty Hassard. See her iconic designs, including close-ups of the collection of dresses and accessories which revolutionised the fashion industry.’

Making-Up the 1960s: Mary Quant Cosmetics (BSL interpreted). V&A Dundee 5 Nov 2020

Join Stephanie Wood for this live talk exploring Mary Quant’s irreverent, playful approach to building a cosmetics brand. With quirky products, clever marketing and bold packaging, Mary Quant cosmetics enabled customers around the world to get the ‘look’ and was fundamental to Quant’s ethos of making designer style affordable to everyone.

Quant: An Ongoing Legacy (BSL interpreted). V&A Dundee 18 Jan 2021

April Crichton of Studio LA FETICHE and curator Mhairi Maxwell explore Quant’s legacy and ongoing impact on contemporary designers tackling the challenges of today. Mhairi Maxwell is a Curator at V&A Dundee, working on the Mary Quant exhibition and our newly commissioned film exploring the approach of three contemporary fashion brands to design, branding and identity.

Quant and Bazaar (BSL Interpreted) V&A Dundee 18 Jan 2021

Step inside the world of 60’s fashion retailing, transformed by Quant through her boutique Bazaar. Curator Kirsty Hassard explores the way Mary Quant disrupted the fashion retailing landscape of the 1960s with her boutique Bazaar, and the shopping shock waves it sent across the UK. Quant’s unique approach to retailing, from window displays to fashion shows, filled Bazaar with the unrivalled vibrancy that became synonymous with her brand, going way beyond the simple merchandising of clothes.

News Centre Maine: ‘Mary Quant, miniskirt designer who swung the 60s, dies at 93’

British fashion icon Mary Quant, 1968: CBC Archives In this clip from 1968, famed British designer Mary Quant talks fabric, boots and makeup. Quant is a British fashion icon, who became an instrumental figure in the 1960s London-based Mod and youth fashion movements.

Mary Quant | Fashion Designer | Interview | Talking personally |1985 | ITV Thames television with Michael Barratt.

Mary Quant, 1966 Archif ITV Cymru/Wales @ LlGC | ITV Cymru/Wales. In this 1966 clip, reporter John Pepper interviews Welsh fashion designer Mary Quant. Born in Wales, Quant has been credited by many as the inventor of the mini skirt and in this interview she talks about the importance of the mini skirt for women, claiming that the mini skirt was designed to give young women a natural elegance and attractiveness when moving, and was a reaction to the stiff and restrictive fashions of her parents era. She hoped to encourage a new sense of femininity and fun for wearers of her designs.

Hilary Alexander, Fashion Editor, Daily Telegraph Mary Quant interview 2009.

Italian film made on Mary Quant in 1972 Mary Quant – Una donna un paese – Regia di Carlo Lizanni 6 Luglio 1972. Produced for the Italian public television service RAI.

Mary Quant appearing on ‘What’s My Line’ US Television in 1966 after collecting her OBE from the Queen at Buckingham Palace.

Pathé films Mary Quant Shoes (1967)

Mary Export Quant (1966)

Mary Quant In Hamburg (1967)

Many thanks to the historian and Goldsmiths’ alumnus David Rogers for assistance and consultation, and the brilliant team in Goldsmiths’ Special Collections Lesley Ruthven and Dr. Alexander du Toit for all their assistance and support with archives.

That’s So Goldsmiths– the history of Goldsmiths, University of London by Professor Tim Crook coming soon.