Goldsmiths’ College staff and students from 1933 in front of the former Royal Naval School Chapel before its conversion into a theatre in 1964. Woman’s Vice Principal Caroline Graveson and then Warden Arthur Edis Dean are first and second left seated front row. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London.

The George Wood Theatre has been the site of prayers, pageants and performances since the building’s original construction as a chapel for the Royal Naval School in 1854.

Tucked away on the north west side of the College Green (formerly known as the back-field) it also served as the Royal Naval School’s biggest teaching space.

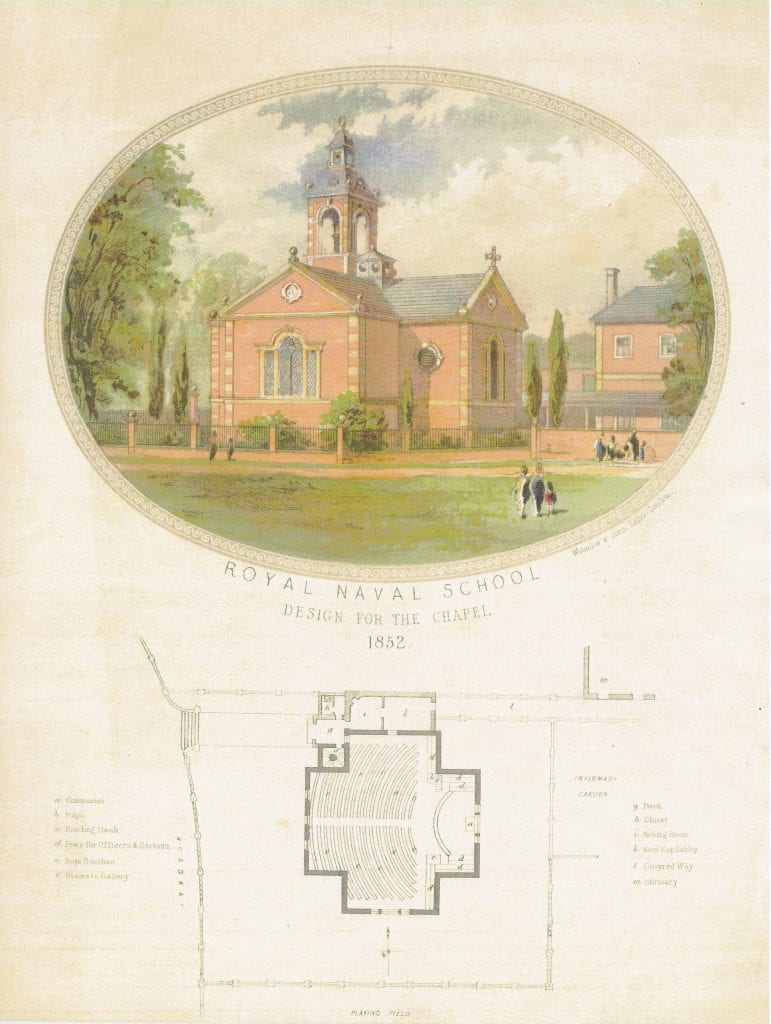

The Chapel’s Original Design

Architect’s design of Wren style chapel and floor plan. Image: Lewisham local archives.

The illustration above is from the special fund-raising brochure circulated in 1852 to accrue the budget for the building from donations.

The target for the ‘Chapel Building Fund’ was £3,000 which in 2018 would have a purchasing power of £406,767.36.

The floor design accurately shows the architecture of the interior that remained the same until the early 1960s prior to its conversion for professional theatre production.

The circular seating maximised the capacity for the 400 pupils for whom the original main building was constructed along with all the ‘servants and officers.’

The brochure said that ‘open seats are provided for the pupils, slightly radiating to the Pulpit, Desk, and Communion Table to the East, so as to afford perfect inspection.’

This aspect was situated on the spur of the building which later became the entrance to the theatre.

Restored Chapel 2018. Image: Tim Crook

The chapel appears to have had a gallery as a staircase is indicated in the plan along with a covered walkway to the infirmary which is now where the Music department is situated.

The view from the playing field was designed to be ‘ornamental and appropriate.’

In 1852 the biggest donor had been Vice-Admiral William Bowles CB with £1,000 followed by a Captain Gladstone with £110.

Bowles had seen action during the Napoleonic wars and served as aide-de-camp to King William IV.

He was MP for the Cornish town of Launceston and his late wife had been the sister of the two times Prime Minister Viscount Henry Palmerston.

The brochure also explained that the ‘primary object of this school is to board and educate the sons of Naval and Marine officers at the least possible expense, and to admit a limited number gratuitously, or on a very reduced payment, preference being given to the Orphans of those who have fallen in the Country’s service.’

The former chapel and lecture room in 1907 during sports day. The magnificent tower was knocked down by an out of control barrage balloon in 1939. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London.

Royal Naval School Chapel

It was even used for drama during the 19th century when the naval cadets put on a traditional Christmas play every year.

So much of its religious symbolism and furniture has been stripped away and lost to history.

This includes the velvet altar cloth, communion chairs, cushions, the stained glass, the massive silver alma dish inscribed with the words:

“Produced for the use of the Chapel of the Royal Naval School by several former pupils, as an offering of gratitude, for benefits derived from the Institution.”

Also lost are the tablets and commemorations to former cadet pupils who died on active service.

The spectacular marble monument to six men who suffered violent and terrible deaths during the Crimean War is now on the wall of the vestibule of the Royal Naval Hospital Chapel in Greenwich.

Illustrated London News 1858.

It is situated behind a bench and visitors would have no idea that the names of the fallen had been educated in the current Richard Hoggart main building in New Cross.

The monument to fallen heroes of the Crimean War now accommodated in the vestibule of the naval chapel in Greenwich. Image: Tim Crook.

Also long lost to history and probably obliterated into brick dust, is the special tablet sponsored by Major-General Sir Henry Floyd.

His son died on active service on HMS Marlborough at Gibraltar.

In 1860 he had erected a tablet giving testimony to the advantages his son ‘had received from the Royal Naval School and as a memorial to the high character he had obtained in the service.’

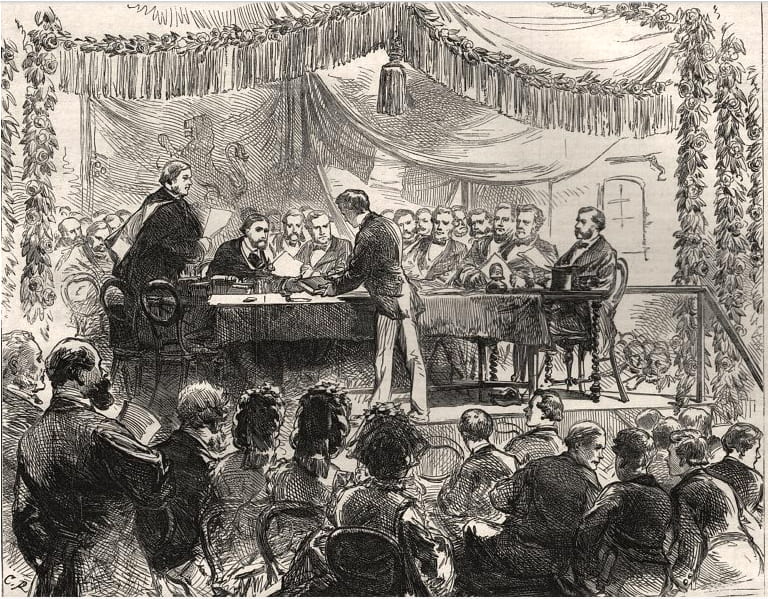

The Chapel was often used for annual prize-giving.

The most spectacular occasion was 1871 when Queen Victoria’s second son Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, presented the awards.

So appropriate when his father, Victoria’s beloved Prince Albert, had laid the large slate foundation stone for the school in 1843, which has been preserved to this day and is such an impressive part of the entrance to the main building.

The Chapel was adorned with flowers and evergreens with a banner over the entrance exclaiming ‘Welcome to Prince Alfred.’

He told the cadet pupils about the close interest that his mother Queen Victoria took ‘in the Royal Naval School and the importance that my father attached to it.’

Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh giving out prizes at the Royal Naval School, New Cross in 1871. Illustrated London News.

The Chapel rang out with cheers as he said how much he looked forward to meeting the boys later on in Royal Naval Service.

He was a serving Royal Naval captain himself.

Prince Alfred was still recovering from a bullet wound received in an assassination attempt in Sydney while on the first ever Royal tour to Australia three years before.

In later life he would succeed to his father’s princedom of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

He had to endure the tragedy of his older son, Albert, dying before him from gunshot wounds inflicted in a suicide attempt after becoming embroiled in a scandal involving his mistress in January 1899.

Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, and later Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Public domain Creative Commons.

Alfred died a few months later from throat cancer leaving his mother Queen Victoria with the grief and agony of outliving husband, son and grandson.

The Royal Naval School was not just an elite military school producing naval and army officers to expand and control the British Empire, and suppress rebellion.

In its own way it was an educational conduit for social mobility.

The school had been established to give opportunity to the orphans of Royal Naval officers and those from more challenging economic circumstances.

It operated as a philanthropic project and depended for its survival on grants, bequests and subsidies; many of them coming from the Royal Family.

One of the school’s famous graduates was the great Shakespearean actor Sir Ben Greet- born in HMS Vulture when moored on the Thames opposite the Tower of London.

Sir Ben founded Open Air Theatre in Britain and was knighted by King George V for making Shakespeare popular and accessible in modern education.

Sports day 1908 showing the former chapel with its distinctive pre WWII tower to the left. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London.

The Chapel was deconsecrated following the School’s move to Eltham in 1889.

And so it lost its ecclesiastical purpose.

Goldsmiths’ teaching and performance space 1891-1964

It became more important as a big lecture and performance space for the Goldsmiths Technical and Recreative Institute in 1891 and then Goldsmiths’ College, University of London from 1904.

Seating of the converted Royal Naval School Chapel used as a large lecture theatre in 1910. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London.

A photograph in the City of London Metropolitan Archives from 1912 shows a small orchestra being conducted with musicians playing classical instruments. The interior still has the appearance of a methodist or non-conformist chapel.

Its distinctive tower, which apparently contained the graffiti of Royal Naval School cadets scratching in their names and initials into plaster, was knocked down by a runaway barrage balloon in 1939, and never fully reconstructed.

After the Second World War it became the focus of the developing subject of performance and drama in teaching.

In the early 1960s Goldsmiths College alumna and distinguished journalist and novelist Val Hennessy recalled for the history project how much fun it was rehearsing in the old Chapel that was used as their theatre space: ‘We sat on the floor, or on those wooden block things; the chapel was hellishly dusty, and full of old chairs and pews stacked up. Very cold too, but we loved it.’

She remembered being involved in a successful production of Christopher Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus that had so much local cultural resonance given the playwright’s killing in a nearby Deptford Inn centuries before.

The distinctly Wren style Chapel interior leant itself to theatrical improvisation and production through the use of curtains and the eccentric circular and tiered seating.

In 1964 the chapel was fully converted into a purpose-built interior theatre space for the expanding and increasingly popular drama and performance teaching courses.

Theatre 1964- to present day

Its walls and stage have echoed to the full range of classical and modern theatrical production.

South facing spur of the Chapel

These examples, randomly selected from the history of production by students in Drama and Performance and collaborating artists, give some idea of the intensity, power, passion, and richness of the work shown in the George Wood Theatre space. To do justice to the full programme would take up hundreds of lines of online text and space.

March 1979. Double-bill of two full length plays Female Transport by Steve Gooch and the Greek classic Ecclesiazusae.

February 1980. Meet Mr Macready by Frank Barrie (married to the then Senior Assistant Registrar Mary Barrie.)

March 1981. The Dog Beneath The Skin by W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood.

June 1982. When We Dead Awaken by Henrik Ibsen and Plenty by David Hare.

George Wood Theatre 1980s to 2017. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London.

June 1983. Too True To Be Good by George Bernard Shaw.

March 1985. Die Driegroschenoper (in German) by Bertholt Brecht and Kurt Weill (music).

May 1985. Workshop by Sir Ian McKellen, then playing the title role of Coriolanus in a National Theatre Shakespeare production.

June 1985. The Revenger’s Tragedy by Thomas Middleton and Top Girls by Caryl Churchill having been toured during the Easter Vacation to universities in Budapest and East Berlin (at that time both behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War.)

February 1986. Annie Wobbler by Arnold Wesker- a reading of his own play.

Restored buildings 2018. Image: Tim Crook.

March 1986. Kathchen Von Heilbronn by Heinrich von Kleist performed in German.

May 1986. Krapp’s Last Tape by Samuel Beckett performed by Max Wall and a production of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame, rehearsed at Goldsmiths’ prior to national tour.

October 1989. Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare.

March 1990. Translations by Brian Friel.

May 1991. Betrayal by Harold Pinter. A Centenary production (Commemorating 100 years of Goldsmiths’ College history).

October 1991. The Rover by Aphra Behn.

Aphra Behn. Yale Center for British Art, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. Public Domain Creative Commons.

May 1994. To by Jim Cartwright.

May 1996. Hindemtth’s one-act expressionist opera Sancta Susanna.

August 2003. Urban Tales: An Adventure in Hip Hop by Second Wave- a youth arts centre in Deptford with Goldsmiths College and a cast of performers aged between 15 and 24.

Political Debate on the Arts

The foyer was refurbished and the theatre modernised in 1978 when it was named after the College’s over-worked, much-loved and eccentric Registrar George Wood.

The then Director of the National Theatre, Sir Peter Hall, gave a lecture on 30th November of that year entitled: ‘The Theatre in its Place.’

He discussed the influence of buildings on the development of theatre from Shakespeare, writing for two to three thousand people in an open theatre, to the fashion at that time for fringe theatre operating in cellars and disused warehouses.

Sir Peter said his argument was ‘a corrective’- an attempt to redress the balance a little at a time when it was fashionable to decry buildings and the effect they had on theatre people.

The rebuilt foyer included the new plaque naming the theatre in memory of George Wood, and visitors included members of his family and the Chairman of the Arts Council, as well as the architect responsible for converting the theatre from its original chapel interior in 1964.

Restored ceiling with theatre’s new lighting gantry. Image: Tim Crook

May 1981. Melvyn Bragg, the broadcaster and novelist, presented the Dean Memoirial Lecture on the subject of ‘Television and Literature: Confluences and Contradictions’ organised by the Goldsmiths’ College Association.

April 1984. High noon challenge to Arts Council cuts. The then college Warden, Richard Hoggart, took up a challenge to debate heavy cuts in theatre grants he had been responsible for in his role at the Arts Council. 46 arts organisations had received the chop. The Stage newspaper described the confrontation as a case of ‘High Noon at Goldsmiths’ College.’ Richard Hoggart was joined by fellow Arts Council boss Sir Roy Shaw. The paper reported that Goldsmiths student Beth Wagstaff had been organising a campaign of picketing of Hoggart’s Goldsmiths’ lectures in protest against the economies that included the National Youth Theatre.

Who was George Wood?

George Wood was College Registrar from 1958 to his death in 1977. A.E. Firth, Deputy Warden and author of Goldsmiths’ College: A Centenary Account, said:

“He overworked constantly, took no exercise and very few holidays, and found it difficult to delegate authority. He did not maintain much in the way of a filing system, apart from those papers he took home each night in four bulging briefcases. There were occasions, after his sadly early death, when the College was surprised by the appearance of awkward documents, relating to contracts of employment, conveyances and the like, of which it had no record.”

Warden Richard Hoggart remembered him as somebody who could get things done that nobody thought was possible. His ‘creative untidiness’ overwhelmed seemingly unavoidable obstacles. He was brilliant at external relations and able to secure deals with local, regional and national government for schemes and funding that were all to Goldsmiths’ benefit. And he was ‘a quite exceptionally nice man.’

The new theatre’s raked seating and light gantry 2018. Image: Tim Crook.

Peter Brindley in adult education recalled George Wood’s enthusiasm:

“…for purchasing or renting houses across the road for the College, or in the surrounding terraces. He was rather like a keen Monopoly player: if he got three houses together on the board we could have a Sociology Department.”

Another former Warden, Sir Ross Chesterman, confirmed that George Wood was a workaholic with an interest and absorption in his work for the College at a ‘total’ level of commitment:

“George was a scientist like myself, and had an extremely clear and quick mind, especially in the early days before his first heart attack. He introduced a most effective and foolproof system of filing records of all kinds, which saved us hours of work and gave great efficiency.

But of all his contributions which helped me most, it was his personal support during the student troubles (1960s), when he would stand at my elbow, as it were, and clearly and quickly would suggest in a few words how each question from the floor should be answered. I am certain that trouble-makers at these student meetings must have felt disheartened in never being able to penetrate our defences.”

Sir Michael Caine workshop 1994

Goldsmiths has conferred honorary fellowships on key figures in the history of contemporary drama including Sir Richard Eyre and Sir Michael Caine. They were both knighted after getting their Goldsmiths awards.

In December 1994 Michael Caine, as he then was, decided to do an actor’s discussion and workshop in the George Wood Theatre after accepting his honorary degree. He said:

“In ten years time, I will be 71. I will be going to the movies at 12 o’clock to get in for half price. In ten years time, I will still be working because I cannot not work!”

This is certainly the case more than 20 years after Sir Michael was at Goldsmiths.

He was asked this remarkable question by one of the drama students and it elicited a quite remarkable answer:

“Many successful actors whose work lies primarily in film and television see it as being similar to the relationship with their wife or husband, and work in the theatre as similar to their relationship to a lover or mistress. Have you thought about taking, or are you planning to take, a mistress? (Sir Michael’s wife Shakira who was in the audience was seen to find the question most amusing.)

I spent time in the theatre, I was 11 years in the theatre, Then I went into movies, and I have been there for 30 years. I never went back to theatre. I also did television. Someone asked me what the difference was between the three. I see that the theatre was a woman who you loved very much and did not care for you, and treated you like dirt; film was a woman who loved you very much and no matter what you did to her, she still came running back; and television was a one-night stand.”

The future

In 2018 it will be re-opened after a 21st century redevelopment as a multiple-purpose theatre space funded to the extent of £2.9 million.

Architect’s plan for new multiple and flexible studio spaces in the George Wood Theatre 2018. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London.

Some of its original features were revealed when decades of panelling was stripped away to reveal the original design and brick-work of the architect John Nash Junior who designed what is now the Richard Hoggart main building first built in 1844.

Artist’s impression of the new interior to be unveiled for opening in autumn 2018. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London.

The renovation space will provide the College with a contemporary theatre seating up to 200 people and two new studio spaces fit for 21st century creative practice.

Many thanks to Rory O’Connell for additional research at the Lewisham Archives Centre.

That’s So Goldsmiths– a forthcoming history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.