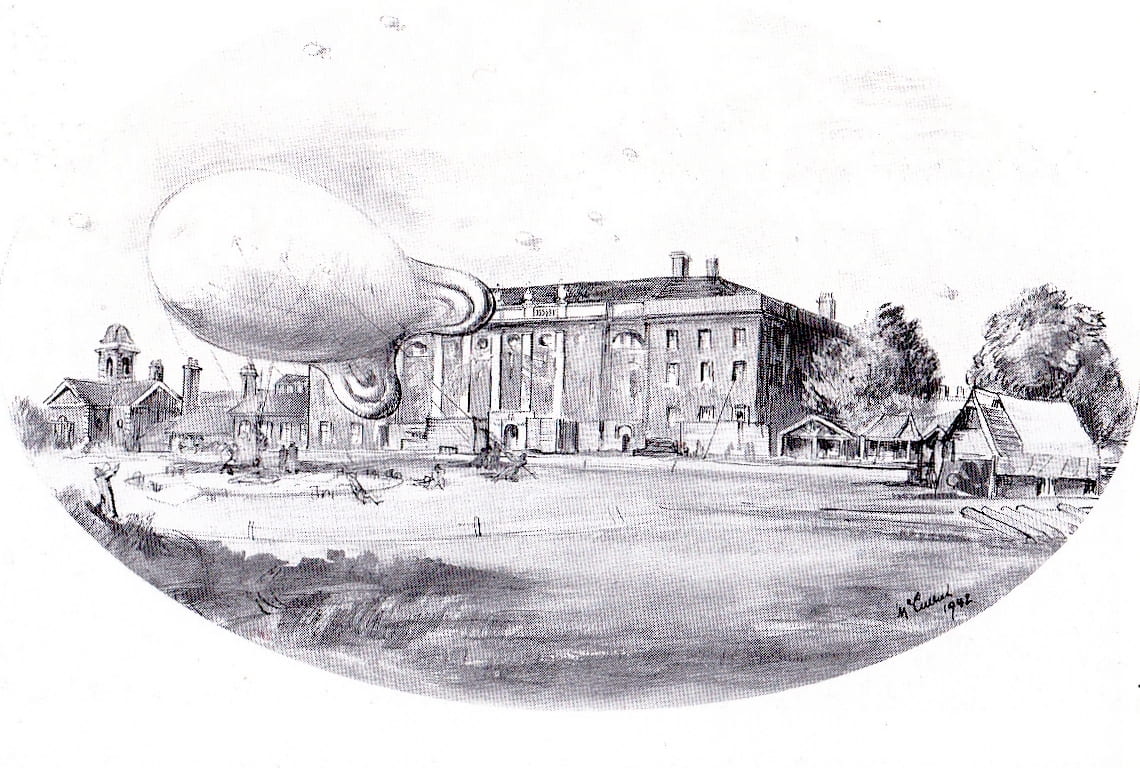

M. McCullick’s ‘Barrage Balloon backfield’ dated 1942 but still including the former Chapel tower which had been largely knocked down by a balloon removed from its moorings by a storm in October 1939.

This country and most of the world is at war with an invisible (to the eye) virus.

And most of the academics and students have been evacuated to their homes to work- apart from a skeleton group of staff providing basic services and looking after the buildings.

These are unprecedented times. We have to wind back the clock of history to September 1939 and the outbreak of World War Two for a comparison.

Goldsmiths had to carry out a complex, stressful and devastatingly disruptive exile to Nottingham University which lasted for seven years.

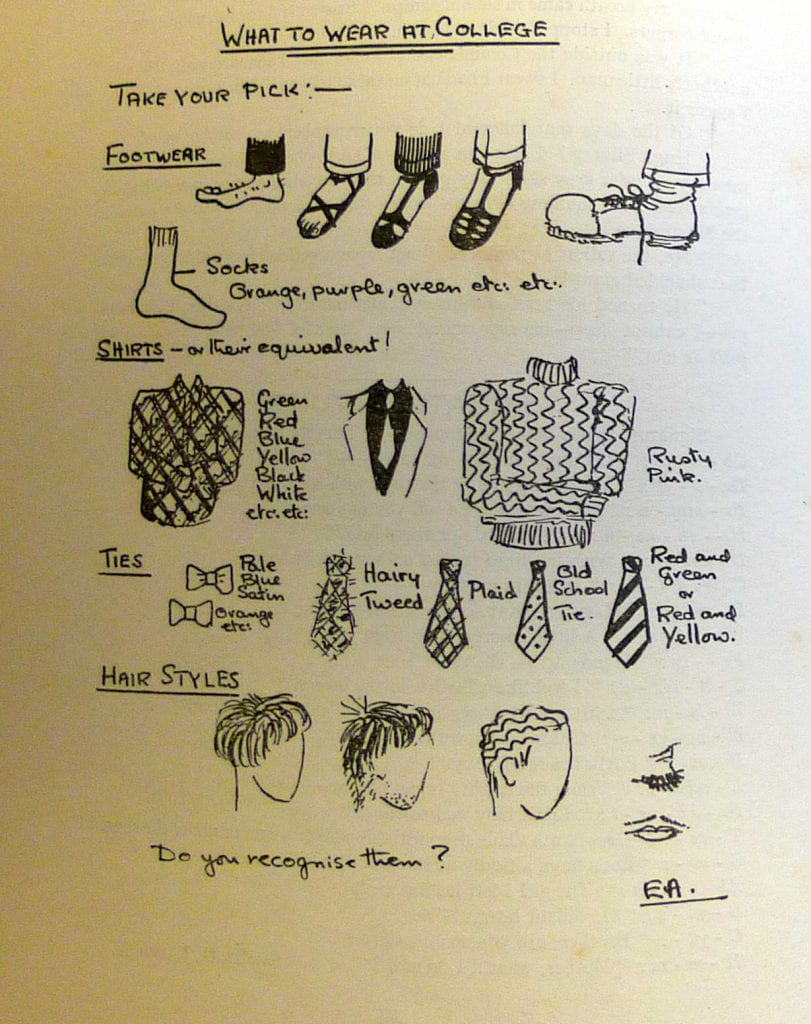

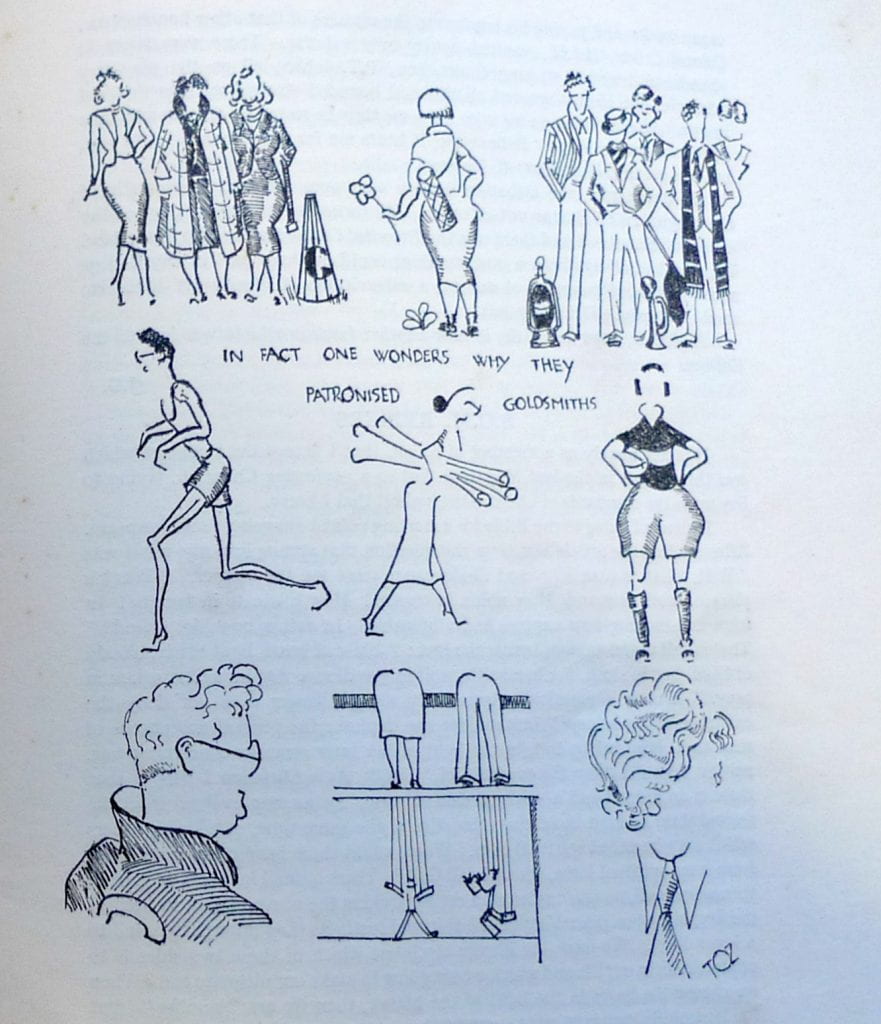

A sketch of fashion recommendations for Goldsmiths’ College students in The Smith magazine for Easter 1939. Image: Goldsmiths Archives

Many of the fashion conscious students soon had to surrender their individuality for the drab constancy of uniforms and make do and mend.

Not everyone left. A small group of Art School tutors and their students worked and lived through the Blitz and ravages of World War.

The College was never the same again.

Sights, sounds, culture and life familiar in 1939 would be lost and when there was a return in 1946, Goldsmiths, and indeed British Society, would be so different.

This three part series tells the story of evacuation, exile and return.

We begin with the crisis of a war of arms and not pestilence being declared Sunday 3rd September 1939.

Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax outside Downing Street after the declaration of war 3rd September 1939. Image: Daily Sketch

To Nottingham and the pantechnicon evacuation

When Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain broadcast his regretful and sad declaration of war by radio on Sunday 3rd September 1939, Goldsmiths’ College had already planned to evacuate most of its staff, students and equipment to University College Nottingham.

It was anticipated that most of the students would be women and a large proportion of the men would be called up through conscription into the armed services.

The mood of the student writing in The Smith June edition for the summer of 1939 was sombre:

“Editorial: ‘The male section of this community, and this concerns future members- up to the next war, will soon be tasting of conscription, a source of controversy and a savoury topic for the “politicians.” Military training and training received at College are poles apart. Whether or no the student character will change as a result remains to be seen’ (The Smith Summer 1939:6).”

A poem by a student described as ‘Tex’ was ‘Written on the horrors of the Spanish Civil War’ which had ended in defeat for the Republicans and the pathetic scenes of hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing over the border to France:

“She plodded through the filth and slime,

The refs of the gutter,

In the footsteps of her Master.

Please (God?) she died, forgot her shame,

She was my love, my Spain !’ (ibid 10)”

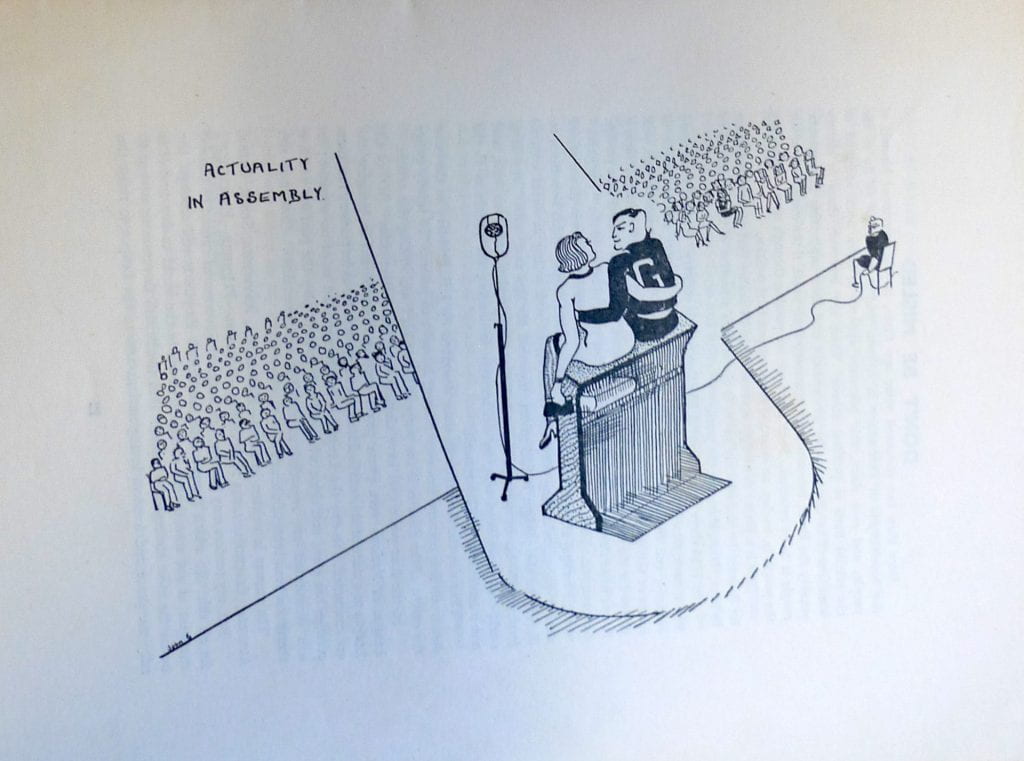

This cartoon in Goldsmiths’ College student magazine The Smith for Spring 1938 pokes gentle fun at a recent publication by staff of their book ‘Actuality in Education’ and references the ritual of compulsory morning assembly with the enjoyment some women students said they derived from observing men students doing physical education classes in the quadrangle in their distinctive tracksuits with ‘G’ sewn onto their backs.

There were more recruits and interest in the College’s Officer Training Corps or ‘OTC’.

Corporal A. Aldred reported on the ambition, later fully realised, to fire the British Army’s formidable Bren machine gun:

“Parades this term have been devoted to general drill and instruction and competition shoots. The former, carried out under the auspices of Sgt. Oldknow of the Grenadiers, have been very well attended, owing to the fact that a former rumour of our having a Bren gun has at last taken shape […] Musketry Camp this year was well attended, and the shooting results were on the whole, good. The most outstanding feature of the more serious side of the Camps was that several members were able to fire a Bren gun. But the most impressive feature for the majority was the spectacle of trooping the colours (the Sgt’s pyjamas) before our more respectable and autocratic rivals, the lads of Battersea Polytechnic (ibid 33).”

Advanced History group in front of the Blomfield building just before the Munich crisis in 1938. Two women students in the front row playfully mock their supposed ‘Advanced’ status by chalking on a blackboard the deliberately misspelt ‘Are they intrested in us? Who did the werk? What ave they tawt us? We don’t know. We are DULL & BACKWARD’

The Borough Council that wanted to take over and asset strip the College

Even though the negotiations for the Nottingham transfer had been completed during the Spring term of 1939 when the German Nazi regime’s full invasion of Czechoslovakia and march into Prague trampled over and rendered invalid everything agreed at Munich, the practical challenge of such an operation was utterly daunting.

The rather predatory Deptford Borough Council had designs on the facilities and spaces that the College offered for War-time civil defence.

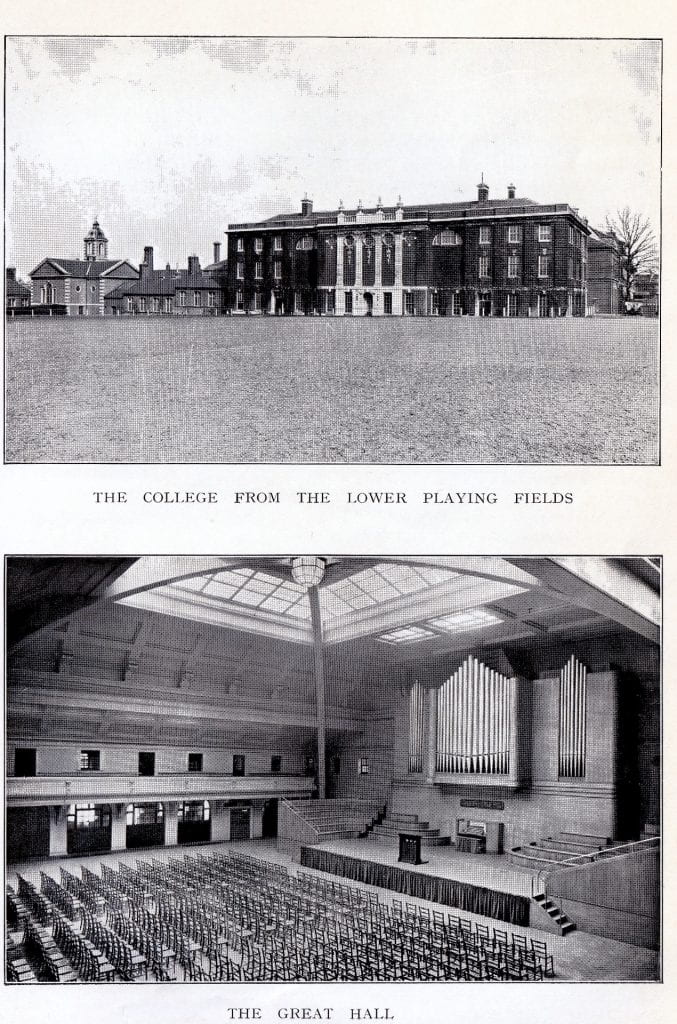

What was being left behind in 1939. Goldsmiths’ College before Deptford Council and the RAF moved in. The back field would be ploughed up. The upper field wrecked with building projects. The Great Hall became a temporary warehouse for ‘stuff’ that needed to go to Nottingham- books, cutlery, crockery, bedding and equipment.

The College thought it had made an agreement for the Council’s use of the building and grounds to be temporary- a short let all over with by the end of the war.

By the time Warden Arthur Dean and 29 of his staff met in the College on the 13th of September, Goldsmiths had been transformed from a place for peace-time teaching and learning into what could only be described as part military camp and an emergency centre ready for heavy rescue and disaster relief.

The upper field was a building site.

The council was constructing a first aid centre and an air raid control centre for a large area of South East London- much of it underground.

Borough Council Air Raid Precautions and local canteen workers had moved in.

The intrusion, albeit for patriotic purposes, was clumsy and rather heavy-booted.

College furniture was effectively requisitioned and, in some instances, damaged.

Nothing had been finalised about rent and liability for the Council rates.

Another art student’s caricature of life in the College in New Cross in 1939: ‘In fact one wonders why they patronised Goldsmiths.’

Over the next two years, solicitors would be consulted, counsel’s opinion sought, legal letters exchanged, and litigation threatened.

Relations would deteriorate further during the War when it became apparent that the council had ambitions to take over the whole college site permanently.

The Royal Air Force had also made themselves at home.

They ploughed up the main playing field with the installation of a Barrage balloon unit and billeted themselves in the Sports Pavilion and five rooms in the main building.

Balloons were intended to defend against dive bombers flying at heights up to 5,000 feet, forcing them to fly higher and into the range of concentrated anti-aircraft fire.

Anti-aircraft guns could not traverse fast enough to attack aircraft flying at low altitude and high speed.

By the middle of 1940 there were about 500 balloons operating over the London area.

The first air raid warning of the Second World War 3rd September 1939. Later air raid warnings and the real thing would soon wipe the smiles from the faces of these Londoners. The boxes they’re holding up are personal gas masks which government hoped would be made and distributed for every person in the population. Image: Daily Sketch

Even the College Dining Room belonged to somebody else day and night as the main canteen for all of the Borough’s A.R.P. workers.

During the summer vacation, the School of Art in the Blomfield building had been shut and bolted less anymore troops of war were tempted to find a use for it.

The headmaster, Clive Gardiner, intended to stay in New Cross and meet the expected terror of aerial bombing and fire from the sky with paintbrush and pencil.

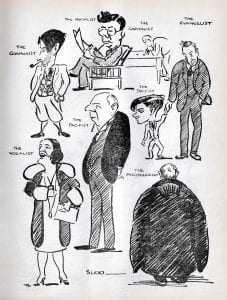

Goldsmiths’ College School of Art taught illustration, portraiture, and encouraged their students to do caricatures of staff and students. The ‘’ists’ of 1939 could be said to be very much around in 2020. The cartoons by ’Sloo’ apparently resembled recognisable students and staff in 1939.

To borrow some of the humour of the 1970s BBC comedy series Dad’s Army, the wonderful neo-Wren main building, designed by John Shaw, had become Air Raid Warden Hodges headquarters ringing to the cry after dusk of “Put that light out!”

As the Goldsmiths’ Warden Arthur Dean and his senior management team pondered all of the indignities of their home being so invaded, they must have wondered when and how Captain Mainwaring and the New Cross equivalent of the Warmington-on-sea Home Guard platoon would turn up.

Early casualties- the old Chapel tower and jobs

To make matters worse on a stormy morning 4th October 1939, the Barrage balloon unit lost control of one of their balloons.

Untethered, the large volume of hydrogen filled cloth became a battering ram in the sky and the first object to meet its destructive force in the high wind was the pretty tower of the old Royal Naval School chapel.

It smashed into the tower, swept away the ornamental dome, and a fair part of the roof of the building, for long used as an important lecture hall, was badly damaged.

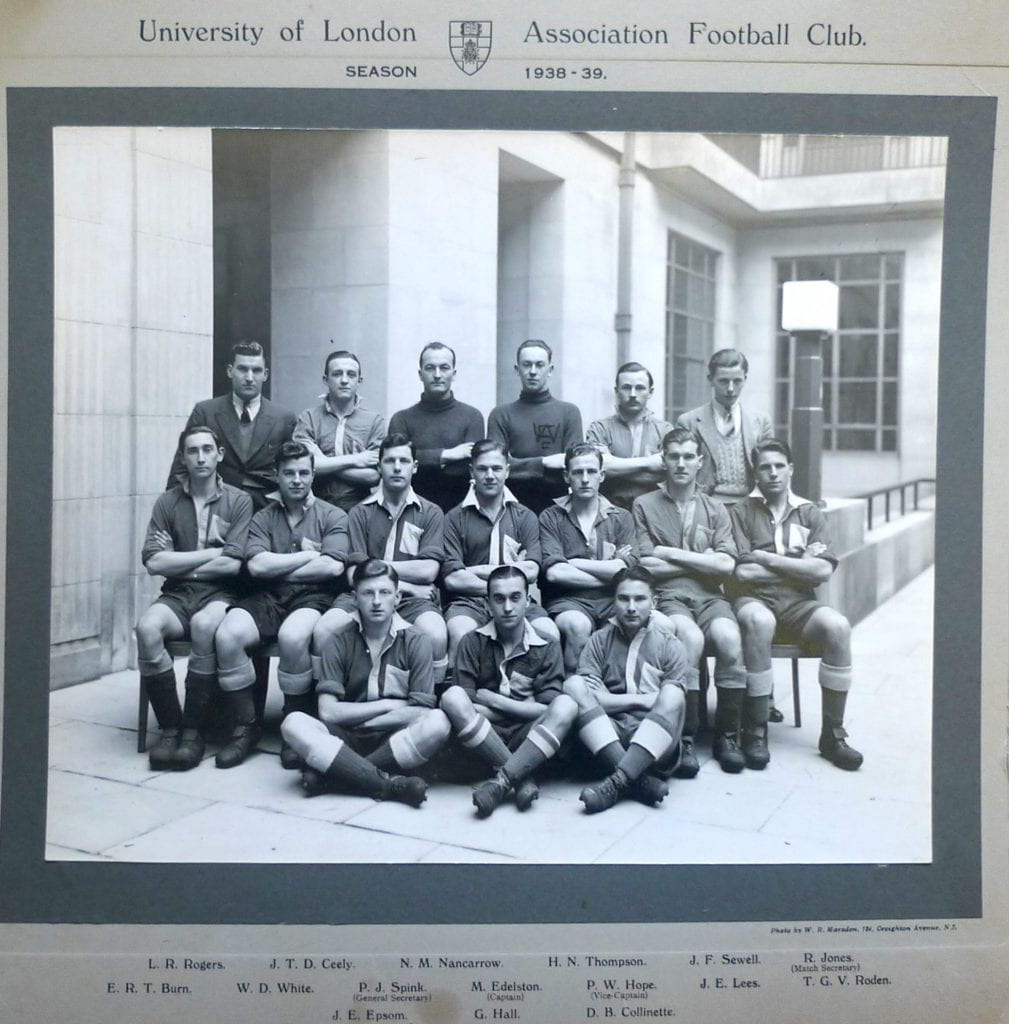

The outbreak of war meant the end of University soccer. Goldsmiths student Eustace Burn (seated far left) had been selected for the University of London’s football team for the 1938-9 season.

This means Goldsmiths College was first a casualty of ‘friendly’ or RAF ‘balloon fire’ during World War Two and not the Luftwaffe.

War ended student rag weeks when the students would dress up, and carnivalesque style, raise money for charity on the streets of Lewisham.

When the College wrote to the Air Ministry asking for compensation it was met with obfuscation and the kind of bureaucratic gobbledygook that civil servants are most likely to indulge in if they are not sure of surviving a world war:

“The Air Ministry is not in a position to authorise payment against your claim, pending the promulgation of decisions to be operated by public departments generally, upon war losses procedure” (College Delegacy 1939:5).

Job cuts- all visiting lecturers, the Associate Lecturers, of today dismissed

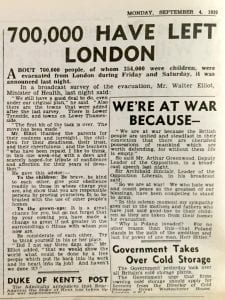

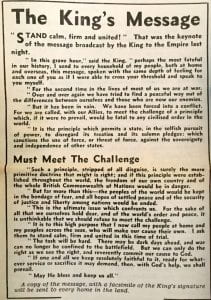

The Monday edition of the Daily Sketch after the declaration of war quoted the King’s message ‘Stand calm, firm and united!’

The King’s Message carried in the Daily Sketch 4th September 1939 ‘Stand calm, firm and united! Meet the challenge!’

But the need for Goldsmiths’ College to leave New Cross was divisive and devastating for a substantial number of people who depended on teaching there as their main source of income.

This was particularly so for most of the Art School’s part-time teachers.

They were all made redundant.

A total of 60 visiting lecturers were sent letters on 4th September telling them that their ‘sessional appointments’ were being terminated.

F.J. Halnon was the encouraging teacher of sculpture and modelling who mentored the Greenwich fireman, George France, to enter his work into the Royal Academy exhibition in 1931.

Halnon had been at the Art School since 1898. He had modelled the bust of the College’s first Warden William Loring.

He was the equivalent of half-time and had been so for 41 years.

This was how most artists in Britain could afford to pay the rent and put food on the table.

On the radio he heard King George VI say: ‘The task will be hard. There may be dark days ahead, and war can no longer be confined to the battlefield.’

A few days later he received a letter from the London County Council saying his battle would now be unemployment and destitution.

Warden Arthur Dean later told the College Delegacy:

“The demand for Mr Halnon’s particular type of work has in recent years very much fallen off, and when the School of Art was partially re-opened the Headmaster was unable to include Mr Halnon in the very small teaching staff required. Mr Halnon’s domestic circumstances were distressing because of family illness, his income had almost entirely ceased, and he had been unable to obtain other work. He had applied to the Board of Education for a pension but, as he had never contributed to any pension scheme, the application has been refused. Moreover, he was still under 60 years of age” (Delegacy 11 April 1940:7).

Arthur Dean had written to the Goldsmiths’ Company and the London County Council asking them to help, but by the time of the Delegacy meeting on 11th April 1940, there had been no reply or result.

Courses closed down and new appointments frozen

The War also meant the shutting down of the Special One-Year Course for the Training of Art Teachers and the Special Third Year Course of Physical Training for Men.

Thirty-two students had to be told that they had no courses to attend and they would have to find something else to do. All third-year courses for Certificated Teachers were having their funding withdrawn by the Board of Education (Delegacy 11 November 1939:2).

Anxiety and confusion near Downing Street. The outbreak of war meant disruption, insecurity and fear. Image: Daily Sketch.

Goldsmiths’ had pioneered and specialised the concept and provision of training and educating teachers over three years rather than two; something that would be recognised in the 1960s and further transformation of the Teacher’s Certificate into a Bachelor of Education degree.

Two recent appointments for the posts of lecturer in Geography and Mathematics had to be told their jobs were unlikely to materialise.

Two long-standing lecturers in Latin and Physics were informed that they were now surplus to requirements.

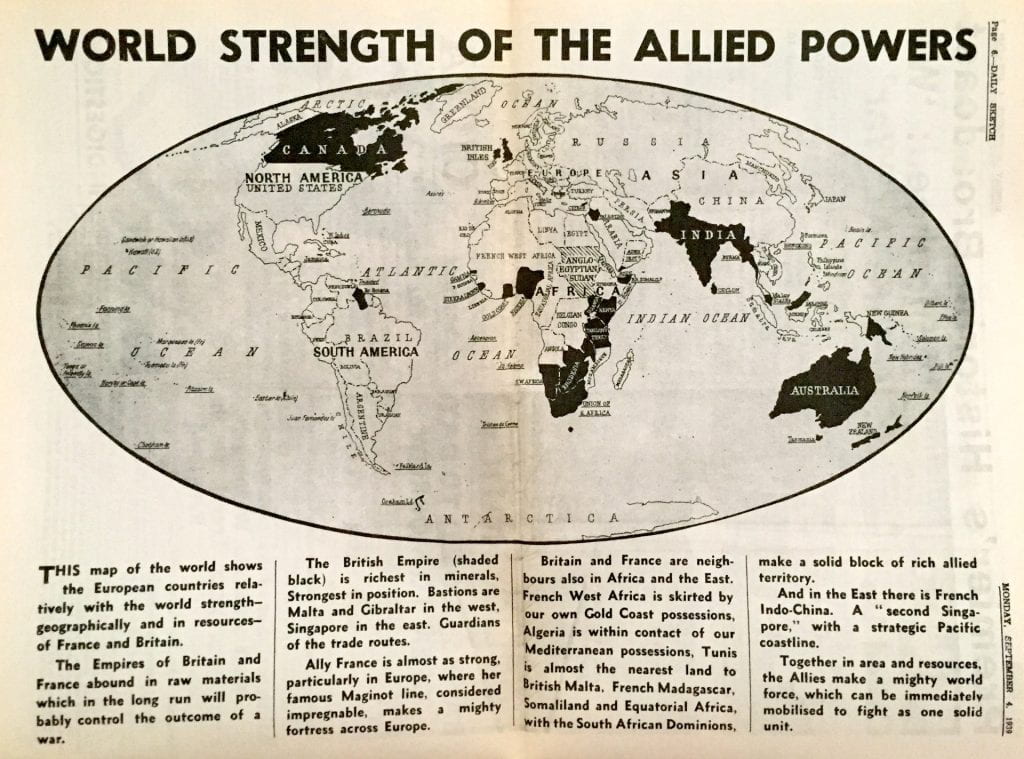

The Daily Sketch would have a centre spread setting out the geography of war and the strength of the Allied Powers. But there would be no replacement geography lecturer at Goldsmiths’ College to teach it. Image: Daily Sketch 4th September 1939.

Support staff not going to Nottingham discovered that they had to find some other kind of war-time service.

The librarians were laid off.

While the College’s Chief Accountant, John Mansfield, stayed on in his office in the main building, his brother Alfred had to go part-time and make up his earnings doing national A.R.P service with Deptford Council.

The council had, however, agreed to continue the employment of all of ‘the house staff – porters, cleaners, stokers, kitchen workers, college workmen and electricians, and some laboratory assistants.

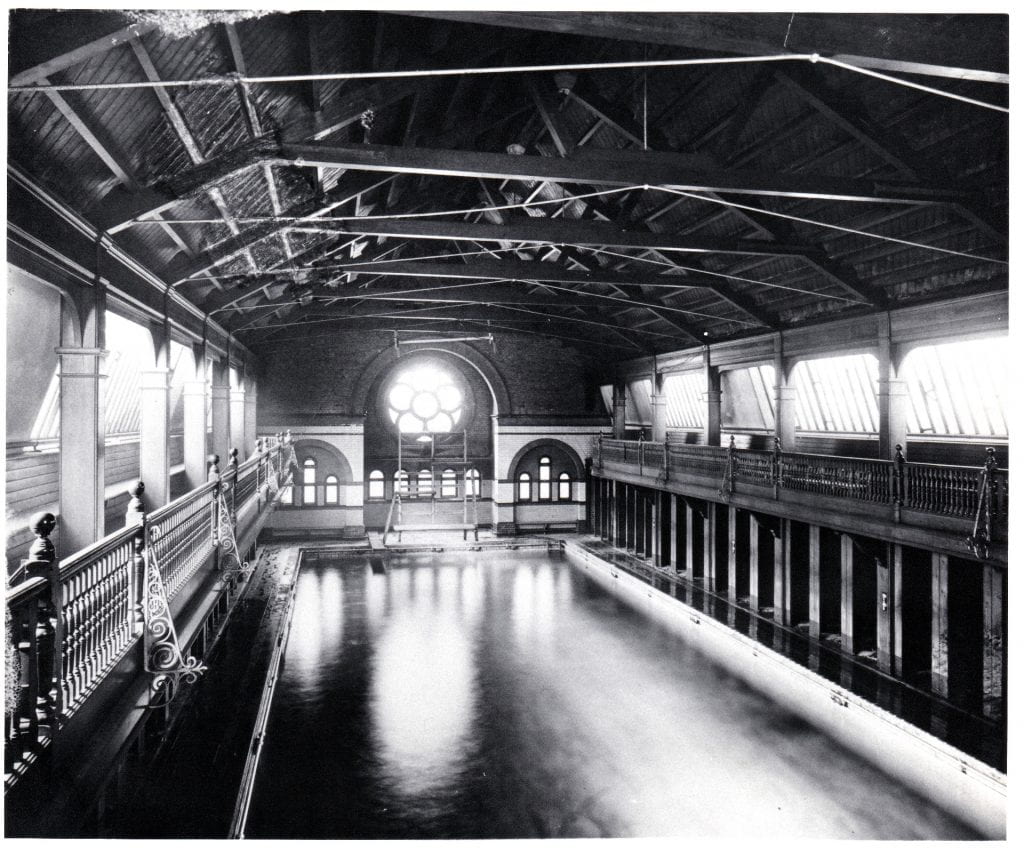

The Goldsmiths’ College Art Nouveau swimming pool in the summer of 1939. The summer sun streaming through the distinctive naval portal window. This is the last time it would ever be seen like this. By the autumn the water had been drained and turned off and the building prepared as an emergency mortuary for those expected to be killed in air raids.

The Artesian well to the College’s lovely Art Nouveau swimming pool was turned off and the empty pool converted into an emergency mortuary to accommodate the anticipated carnage of multiple casualties from Guernica style bombing raids.

Time to go, organising the evacuation, and infants first to Lady Norah’s

When Germany invaded Poland on the 1st September 1939, the College’s Nursery School was the first to be evacuated on that very day.

An original party of 15 children, Superintendent Miss Silcock and her assistant Audrey Burton, and seven voluntary helpers, six of them being mothers of the children, travelled to Lady Norah Howard’s House, Wappingthorn Manor, near Steyning in Sussex.

The beautiful house and grounds were an enormous contrast to living in urban Deptford.

Two mothers and their children preferred to return to South East London by the end of November.

The remaining children were in the care of the Froebel trained Certificated teacher Miss E.M. Taylor on a salary of one pound ten shillings a week (Delegacy 11 November 1939:6).

The safety of younger children from expected heavy bombing of the cities was a national obsession.

Even though the wailing of the sirens on that sunny Sunday following the Prime Minister’s broadcast from Downing Street turned out to be a false alarm, millions of Londoners did take shelter.

Another air raid warning had sounded at 2.a.m. with the all clear signalled an hour later.

On the following day nerves were frayed and people were beginning to discover what it was like to have a daily existence with not enough sleep.

Stop press news. Sinking of the passenger liner SS Athenia- the day after War broke out. The United States also made it clear it would remain neutral.

And anyone reading their copy of the Daily Sketch would have read in the ‘Stop Press News’ that a passenger liner sailing to Canada with evacuees on board had been torpedoed.

The capital letters printed at right angles to the back-page text revealed: ‘Ministry of Information state S.S. Athenia with 1,400 passengers on board, has reported to Admiralty she had been torpedoed’ (Sketch 4 September 1939:24).

98 passengers and 19 crew had been killed in the sinking of this unarmed civilian vessel in the icy waters of the Atlantic, North West of Ireland.

Many of the victims were American and Canadian, including a ten-year-old-girl from Hamilton, Ontario.

It was the Second World War’s first war crime.

Diverting the students from New Cross to Nottingham

After the infants had gone, the College next had to contact all of its incoming and returning students to find out who was prepared to go to Nottingham.

Letters were sent out on 22nd of September.

369 out of 443 replied saying they were happy to do so.

There was not the expected fall-off in men as it had been decided not to call up 18 and 19-year-olds for service in the armed forces at this time.

Students had to make their own way there and were expected to arrive by early afternoon Tuesday 3rd of October using train services from St. Pancras and Marylebone.

It was proposed that all the women students could be accommodated at Hugh Stewart Hall in University College, Nottingham.

The men would have to be found lodgings.

All the students were advised to keep down the total amount of their personal belongings, but to bring with them a pocket torch showing a blue light.

As men were living out of lodgings, they were advised to bring their bicycles.

As there was a shortage of laundry, women students staying at Hugh Stewart Hall were told they must provide for themselves four sheets, three pillow slips, three face and bath towels, three table napkins with a ring and their regulation gas mask and box.

In these days before the National Health Service, students were advised that the cost of medical attendance in excess of four visits would have to be paid for and any students who had been in contact with infectious illness during the vacation must bring a medical certificate to show that they were free from infection’ (Delegacy 12 September 1939:3).

The contingency of war meant that men who had reached the age of 20 risked rude interruption of their studies and the conscripting despatch to the boot camp:

“Men students who have already attained the age of 20 must realise that the earlier concessions about postponement of military training for students no longer apply. The Government have not yet made any clear pronouncement about this, but it is possible that such men may be called up before the end of the session or even before Christmas. The College is obviously unable to give any guarantee in this respect and cannot offer any further guidance as to individual decisions: but if men are not able to complete the 1939/40 session some refund of fees will be made” (ibid).

As Goldsmiths’ College students made their way to Nottingham, the King and Queen stayed at Buckingham Palace and went out to meet Londoners on the streets. Image: Daily Sketch

Pantechnicons for the books, bedding and crockery

More than twelve pantechnicons were booked to transport the massive amounts of equipment of all kinds, including books being mustered in Deptford.

One thousand volumes were selected from the library and packed up in the Great Hall.

Around one thousand Goldsmiths’ College library books were piled up in the Great Hall for packing in boxes to go to University College, Nottingham where they were used in teaching for seven years. Given the Luftwaffe’s destruction of the library by incendiaries in 1940, their selection was an effective reprieve from becoming the collateral damage of war.

200 beds with bedding, followed by crockery and kitchen equipment from the Hostels filled the convoy of lorries assembling in Lewisham Way.

Goldsmiths’ lecturers travelling in advance of the students to manage the arrival of the transport lorries were pleasantly surprised at how quiet it was in Nottingham, where cleaner air and the very fine Hall of Residence in Hugh Stewart Hall were in stark contrast to the heavy and throbbing traffic on Lewisham Way, the myopic and suffocating London smogs, and the threadbare and gloomy main building first built in 1844.

No sooner had most of the staff arrived than two of them had to leave following mobilisation. The Physical Education lecturer and England Hockey international player, Percy Thomas (P.T.) Rothwell, had a commission as second lieutenant in the Tank Corps and the French lecturer Dr. Arnould was called up into the French Army.

The uncertain future

Warden Arthur Dean said September was:

“…a strenuous month […] with much hurrying to and fro, vast correspondence with scattered staff and students and a great deal of physical labour over the transport of gear whenever we could lay hold of a pantechnicon” (GCOSA Yearbook 1939-40:1-4).

In a letter to alumni he warned them that should they visit their old College in New Cross:

“…you would hardly find the College exhilarating in its sandbagged and blacked-out condition. The R.A.F. occupy several rooms at the South Eastern corner and have a balloon in the grounds, and their burrowings and lorry-runnings have played havoc with the Lower Field. The Upper Field has been devastated to make a large underground A.R.P. Control Centre and large parts of the buildings are in occupation by the Deptford Borough Council for First Aid Post, and A.R.P. purposes. A day-and-night canteen for auxiliary workers in the Borough is in operation in the College Dining Hall and kitchen, where the lights have never been out since the war began’ (ibid). Arthur Dean ended his long letter with the rumination that ‘The future – particularly the immediate future – is obscure, but there will be a world to rebuild after the earthquake, and Goldsmiths’ craftsmen will have their share in that. Meanwhile, I hope we shall keep together in spirit – new Smiths’ and Old Smiths’ – and that all of you will make some effort to keep in touch” (ibid).

Arthur Dean and his colleagues, the students and the alumni could be forgiven for fearing whether the College would ever be able to return to its home in New Cross.

And the horrors of a Second World War would inevitably mean that some Old Smiths’ would never be able to keep in touch when they became casualties of the conflict and new names to be carved on the College’s memorial.

Lives and futures were to be interrupted and terminated.

Future developments in British education were also paused abruptly.

The 1st September 1939 was supposed to have been the day when the school leaving age was raised to 15.

In December 1938, the findings on Secondary Education with special reference to Grammar and Technical High Schools, generally known as the Spens Report, set out a new policy of a clean break between primary and secondary education at the age of 11 and a half.

It reiterated that secondary schooling should be free to all, but also sufficiently diverse to serve a wide range of abilities.

It retrieved and hailed the late 19th Century recommendations of the Bryce Commission that there should be three types of secondary school, Grammar, Modern and Technical High.

The ideas and hopes were there, but there was no time.

And as Kenneth Richmond observed:

“So far as education in this country was concerned, Hitler’s infernal genius could scarcely have chosen Der Tag with more devastating precision. The plans of Bryce and Spens went all agley. Chaos descended long before the bombs” (Richmond 1945:122).

Then and now. What was different in 1939 and what was rather familiar now?

The distance in time is 81 years.

In 1939 Britain was the capital of an imperialist European power and sociologically it was class-ridden, sexist and racist.

Students hoping to be language teachers in 1939 and packing their suitcases for Nottingham would have probably bought the Daily Sketch as their newspaper of choice because it always had a page providing the news in French, English and German.

Page of the Daily Sketch 4th September 1939. The news in three languages daily. The theme on this momentous day was ‘How we declared war on Germany.’

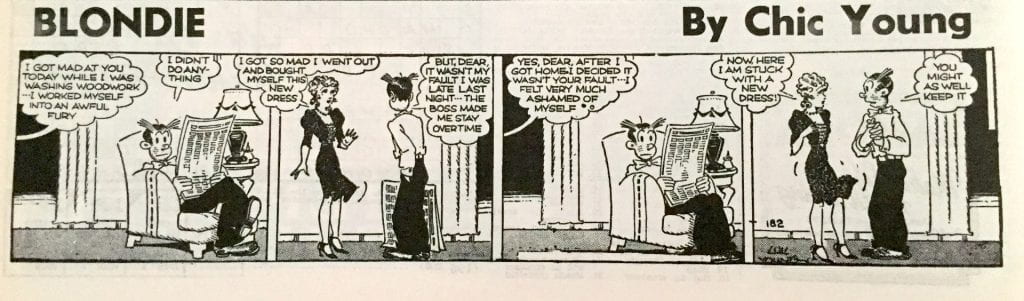

The Daily Sketch’s most popular strip cartoon was called Blondie and its representation of women would now be regarded as stereotypical and offensive.

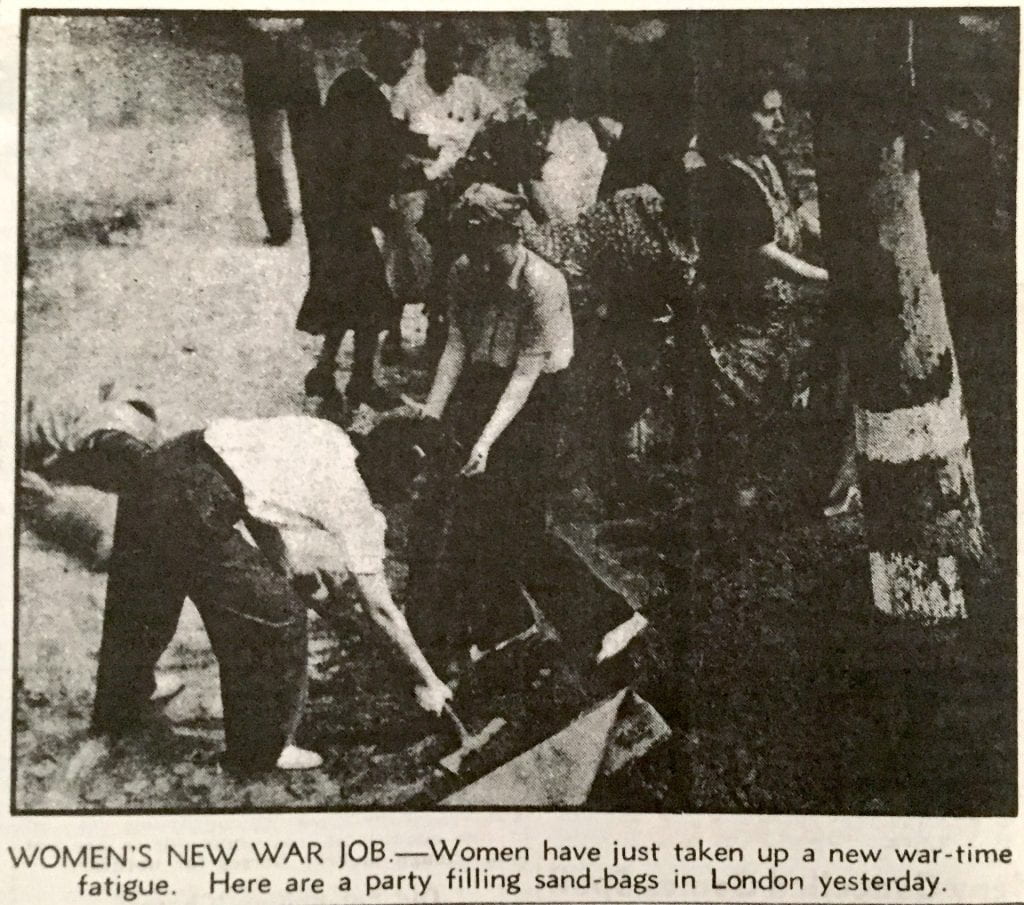

When women joined in the civic emergency task of urgently building air raid defences, their filling of sandbags would be noticed.

The threat and fear in September 1939 was the idea and reality of total war.

At the beginning, the British population expected terrible air-raids, mass casualties and the use by the Germans of gas and chemical warfare.

In 2020, the threat and the fear is caused by a pandemic virus and perhaps something historically last experienced during the Great Plague of 1665.

In 1939 the outbreak of war would mean the closure of shops, business and services.

People would also try to leave London in addition to the large-scale evacuation of children to the countryside.

Many Londoners with second homes would skedaddle.

Large numbers of the aristocracy would depart for their mansions and country estates.

Many middle-class people with private incomes would become long-term residents in hotels in country villages, towns and seaside resorts.

In 1939 the government introduced national identity cards and the developing impact of U-boat attacks on merchant shipping resulted in the introduction of rationing.

Petrol was the first commodity to be controlled in 1939.

On 8th January 1940, bacon, butter and sugar were rationed.

This was followed by successive ration schemes for meat, tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, eggs, lard, milk and canned and dried fruit.

There was recognition that farming and food yields needed to be substantially expanded.

There were plans to form a land army open to women to ensure the increase in food crops could be harvested.

On 4th September panic-buying was not so much for toilet-rolls, hand sanitiser and dried pasta, but sand for sandbags.

In 2020 there is a need for personal protection equipment on the part of health workers.

The presence of decontamination suits was not an unusual sight in 1939 since civil defence was preparing for First World War style gas attacks.

One clear similarity between then and now is that police had to be deployed to enforce emergency powers.

In 1939, the police even had to deal with the welfare of the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop’s dog that he had left behind when he returned to Berlin after his time as the German Ambassador to Britain.

The closure of London schools meant children would be at home unless being part of the evacuation scheme.

How to amuse your children when at home was certainly a theme of newspaper feature writing.

What was different? Apart from newspapers that substantially slimmed down to two or three folded sheets, there was only one radio station- the BBC.

The very limited schedule of hourly news bulletins, records and an excess of Sandy McPherson playing the electric theatre organ generated so much boredom, exasperation, and protest that both the BBC and the government would realise the general public needed entertainment and culture in these difficult times.

There was no television, since its early years of broadcasting from Alexandra Palace was shut down.

Cinema and newsreels would prove popular, but there were no internet services, online platforms and smartphones.

No digital video-conferencing.

Telephones yes.

A majority of the population smoked.

Aspro was the painkiller of choice; not paracetamol.

And there were many advertisements for remedies for flatulence, indigestion, and irregular bowel movements.

‘CICFA for sixpence’ did not last, but the product name was an acronym for ‘Conquers indigestion, constipation, flatulence and acidity.

‘Chilprufe’ or pure wool underwear for children would not win any marketing awards.

In 1939, scratchy, woolly underwear seemed all the rage.

- Cigarettes

- Painkillers

- Laxatives

- Woolly underwear

Goldsmiths emptied to be re-constituted through the generous hosting of University College Nottingham.

The teaching largely remained the same. Life continued to be face to face and social.

In 2020, the retreat and dispersal physically is into the home and the digital realm.

The controls and rules of the emergency are counter-social and anti-social in the physical sphere.

In 2020 we are connected to work in multimedia cyberspace.

The switch from operating in a physical location to an online one had to be achieved in seven days.

In 1939, the College’s senior management had six months, April to September, to plan the move to the refuge of a provincial university college in Nottinghamshire.

The Second World War would fundamentally change British society after its outbreak in 1939.

The fascinating question in 2020 is whether the COVID-19 pandemic will fundamentally transform the very nature of social existence, the distance between work and home space, and the culture of Higher Educational teaching and learning.

This is the first draft of another chapter in the history of Goldsmiths, University of London.

Coming next- Part Two: Exile

Bibliography

Daily Sketch newspaper, 4th September 1939.

Goldsmiths’ College Old Student Association (GCOSA) Yearbook 1939-40.

Goldsmiths’ College Delegacy minutes for 1939

Goldsmiths’ College Delegacy minutes for 1940

Richmond, Kenneth W., (1945) Education In England, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books

The Smith Magazine, Goldsmiths’ College, Summer 1939.