Officers of the 88th Regiment. Crimean War by Roger Fenton. Image: US Library of Congress, Public Domain.

Six young men educated in the corridors and rooms of the Richard Hoggart main building died a variety of horrible deaths between 1854 and 1855.

They were killed in the biggest clash of the superpowers of the Victorian Age.

This is the secret history of Goldsmiths’ Crimean War heroes.

They were students of the Royal Naval School, which occupied the neo-Wren style building designed by John Shaw Jr. between 1844 and 1889.

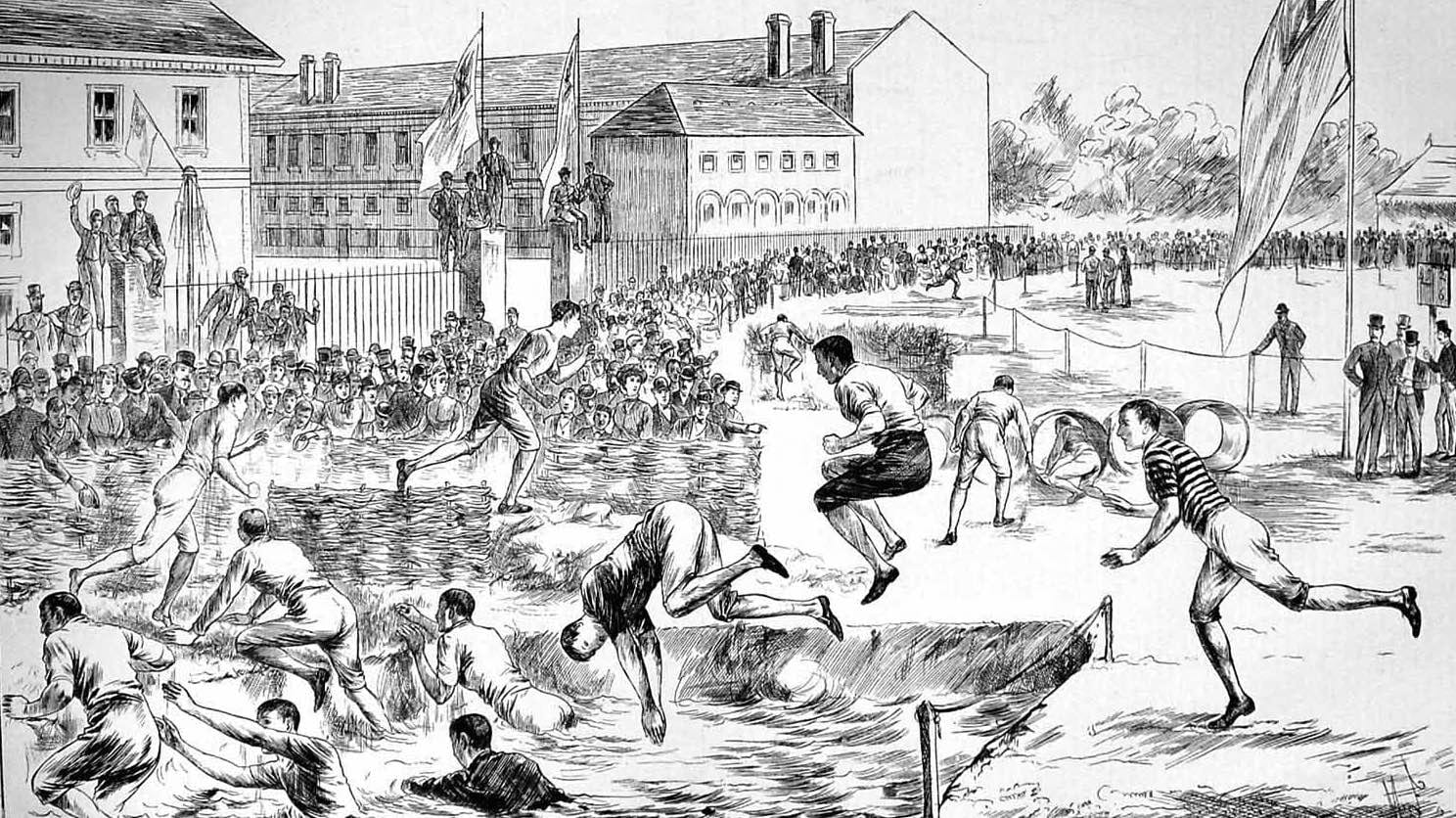

Sports Day on playing fields of Royal Naval School, New Cross. Image: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News 4th August 1883

The story of the Royal Naval School is as chaotic and ‘finger-tips on the cliff-edge’ as that of the College.

At that time what we now know as the Great Hall was a large quadrangle open to the sky where the likes of cadet pupils, Edward Carrington, Edwin Richards, R.O. Lewis, Richard Morris, Sidney Smith Boxer, and James Murray did their parade ground drill.

The teaching rooms off the ground floor corridors are where they were taught mathematics, technical drawing, navigation and the classics.

And the corridors and ante-rooms on the first floors of the current main building are where they slept in hammocks sometimes looking out of the large windows at a clear night sky filled with the Milky Way.

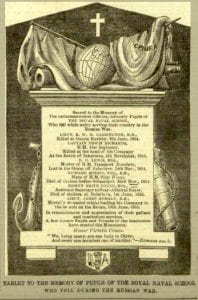

Crimean War Tablet at New Cross Royal Naval School Chapel. Image: Illustrated London News 27th March 1858.

They had a magnificent carved marble memorial dedicated to their memory on the wall of what is now the George Wood theatre.

This had originally been built as the Royal Naval School’s chapel:

‘Sacred to the memory of the undermentioned officers, formerly pupils of the Royal Naval School, who fell while nobly serving their country in the Russian War … in remembrance of their gallant and meritorious services.’

Each of the young men died in ways that symbolised the nature of the Crimean War and how it is remembered.

Great Britain became an ally of the French and what is now modern day Turkey to counter the military expansionism of Tsar Nicholas the First.

He wanted to replace the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, and acquire the Crimean peninsula so as to guarantee access for the Russian fleet’s easy passage between the Black and Mediterranean seas.

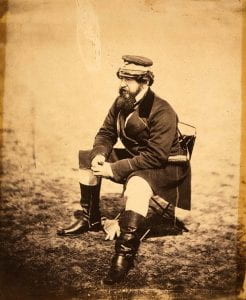

This was the war which inaugurated the role of the foreign correspondent through the critical despatches of Times reporter William Howard Russell.

Times Crimean War correspondent William Howard Russell. Image: Roger Fenton, US Library of Congress, Public Domain.

It was the first British involved conflict with officially commissioned war photography.

It was very much the first modern media war as the laying of telegraph cables meant news could reach Britain in a matter of hours rather than days.

And the New Cross soldiers and sailors were in the thick of it.

Lieutenant Edward Carrington was killed on 6th June 1854 in a little known Royal Naval equivalent of the Charge of the Light Brigade.

This was on water opposite deadly gun batteries at Gamla Karleby – what is now the modern Finnish Baltic town of Kokkola, in the gulf of Bothnia.

He was killed as were most of the men in his boat.

The Vice Admiral and Commander in Chief of the Baltic force, Charles Napier, publicly castigated Captain Glasse of HMS Vulture for:

“…sending boats to attack a place so far distant from his ship without any apparent object, which has led to the melancholy catastrophe on this occasion.”

This was the war that exposed the inadequacies of military medical supplies, care and treatment.

Florence Nightingale. Public Domain.

While Florence Nightingale was struggling in vain to save lives at the hospital in Scutari, tens of thousands of men died from cholera, dysentry and other diseases.

They included the former New Cross cadet Richard Morris who was Mate of HMS Wasp and died of cholera before Sebastopol on 24th November 1854.

The fate of Sidney Smith Boxer Esquire was particularly poignant.

He was assistant secretary to his uncle Rear Admiral Boxer who was being heavily criticised for the failures in the distribution of ordnance and supplies.

Sidney died from cholera at Balaclava on 1st June 1855.

His uncle, exhausted from the strains of his role and grief over the death of his young nephew, succumbed to cholera and died a week later.

Captain Edwin Richards of the 41st Regiment died from multiple bayonet and gunshot wounds at the head of his company in the Battle of Inkerman 5th November 1854. His grieving father in Ireland was told:

‘…he was surrounded by Russians. Refusing to yield himself a prisoner, he shot four of his opponents, and killed two with his sword – thus dying the noblest and glorious death a man could die, without pain; shot through the body and stabbed by several bayonet wounds, he suffered no pain as death must have been instantaneous.’

The Master of HM Transport Resolute, R.O Lewis Esquire, was another Royal Naval School New Cross graduate.

Balaclava Harbour 1854. Image: Roger Fenton. US Library of Congress, Public Domain.

He drowned when a hurricane swept through Balaclava harbour on 14th November 1854 sinking and smashing transport ships.

Richard Nicklin, a civilian photographer, sent to take pictures of the conflict to build public support for the war, was also lost at sea, along with his assistants, photographs, and equipment.

Roger Fenton and his unit were sent to replace him and survived the journey, the weather, diseases, and all the dangers of the conflict.

The final New Cross Naval School victim was Lieutenant James Murray of the Royal Engineers.

He was mortally wounded while leading an assault on the Redan fortification on 18th June 1855.

Mary Seacole by William Simpson (1823-1899) Image: Public domain.

He could have been attended by the Jamaican born pioneer paramedic Mary Seacole who was seen going out into the battlefield to provide comfort and assistance to those struck down by artillery or musket fire.

The memorial tablet to these men was taken down when the chapel was deconsecrated following the Naval School’s move to Mottingham in 1889.

The building was converted into a lecture hall in 1891 and then a theatre in 1968.

The monument, designed by sculptor Edward James Physick, is now in the vestibule of Greenwich’s Royal Naval School Chapel, with no indication that it refers to the New Cross educated veterans.

That’s So Goldsmiths, a new history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.

Goldsmiths History Project Podcast by Tim Crook