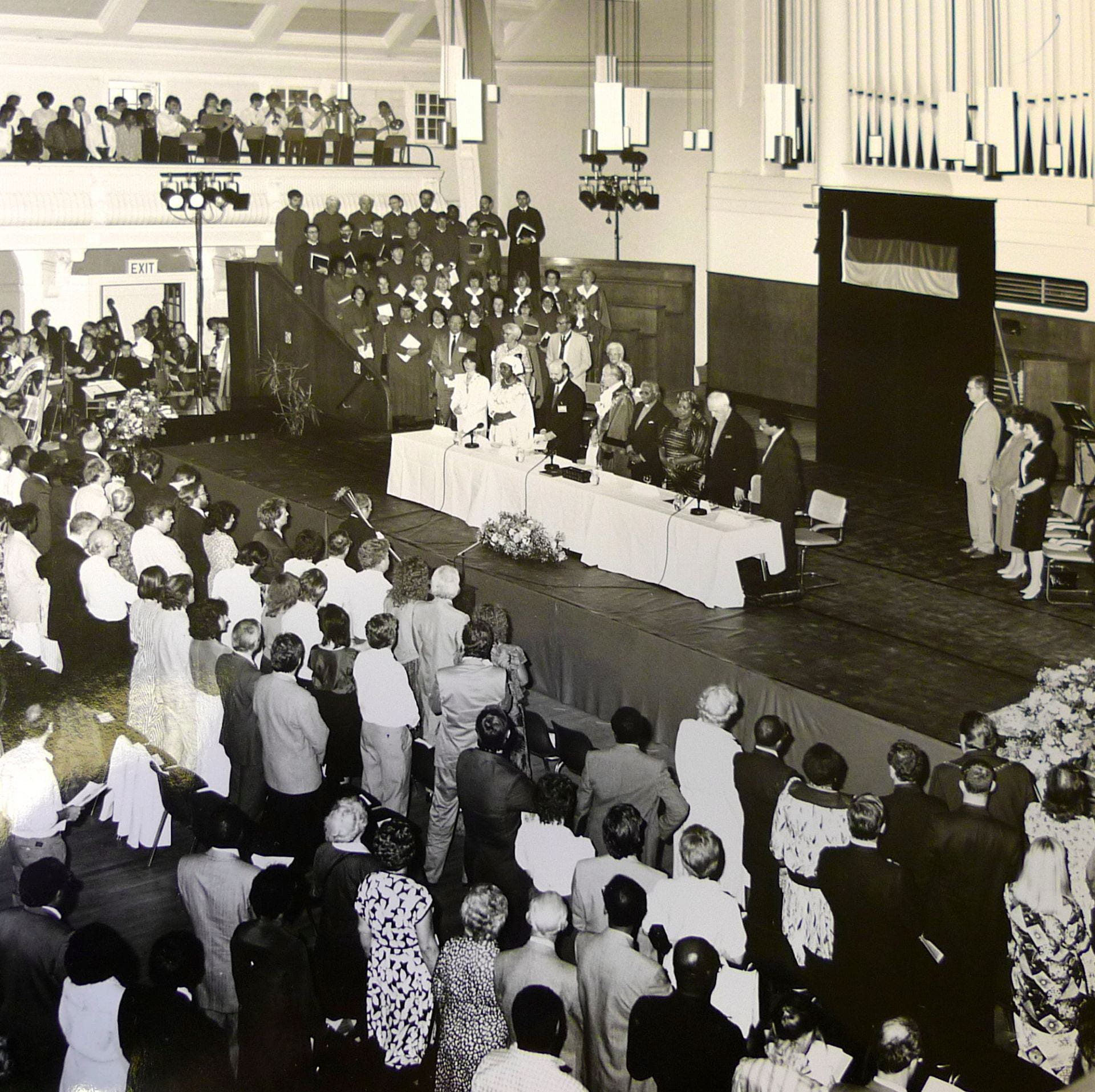

The Admission of the Most Reverend Desmond Tutu as an Honorary Freeman of the London Borough of Lewisham, Great Hall, Goldsmiths’ College 4th May 1990. Image: Copyright Goldsmiths archives.

Sir Desmond Mpilo Tutu is the world’s most revered living anti-apartheid and human rights activist.

He was the first black African to hold the position of Bishop of Johannesburg and then Archbishop of Cape Town.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for his advocacy and activism of non-violent opposition and protest against the South African apartheid regime. In his acceptance speech he said:

“This award is for mothers, who sit at railway stations to try to eke out an existence, selling potatoes, selling mealies, selling produce. This award is for you, fathers, sitting in a single-sex hostel, separated from your children for 11 months a year… This award is for you, mothers in the KTC squatter camp, whose shelters are destroyed callously every day, and who sit on soaking mattresses in the winter rain, holding whimpering babies… This award is for you, the 3.5 million of our people who have been uprooted and dumped as if you were rubbish. This award is for you.”

His steadfast and dignified campaigning for the rights of Black South Africans is credited with playing a key role in persuading the apartheid regime in South Africa to relinquish power, release Nelson Mandela and hold democratic elections in 1990.

Goldsmiths, University of London hosted Archbishop Tutu’s return to London to receive the freedom of Lewisham in May 1990.

Students and staff created the music and poetry which celebrated his achievements in bringing about peace and reconciliation.

The South African cleric and theologian’s links with Lewisham had been and remain affectionate and meaningful.

Living and ministry in Grove Park

Admission as an Honorary Freeman of the Borough of Lewisham was the highest honour the Borough could bestow on the Nobel Peace Prize winner who had led the wide-ranging ecumenical opposition to apartheid.

The 14th Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, both Nobel Peace Prize laureates, in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 2004. Image by Carey Linde. CC BY-SA 3.0

What was less known internationally, though cherished locally, was that he had lived in Lewisham during the early 1970s and acted as honorary curate at St Augustine’s Church, Grove Park for three years while working as Associate Director for Africa of the Theological Education Fund.

He was no stranger to London having earlier studied for and been awarded a BA and MA in Theology at King’s College, University of London.

In fact, the Archbishop inadvertently gave his name to a key aspect of University slang in the United Kingdom because a 2:2 degree became known as ‘a Desmond Tutu.’

A recent online guide to university jargon said: ‘You can’t go wrong with a degree nicknamed after a South African Anglican cleric and human rights activist.’

The sobriquet is meant to be respectful and consoling about the achievement of obtaining a university degree whatever the hierarchy of classification and grading.

This remarkable and memorable ceremony took place in the packed Great Hall of Goldsmiths and was hosted and organised by the College.

Archbishop Tutu was welcomed by Mary Barrie who was Goldsmiths’ Academic Registrar at the time.

Speeches were provided by Archbishop Trevor Huddleston, who’d known Archbishop Tutu since his schooldays, Paul Boateng MP, and Deptford MP Joan Ruddock.

The Mayor of Lewisham said:

“In honouring Archbishop Tutu, this Council is paying tribute to his courageous non-violent struggle against apartheid and the inspiration he has given to oppressed peoples everywhere; and we take pride in him as a former resident of the Borough. Above all we are recognising his human qualities: his courage and enthusiasm, his intellectual vigour and wit, his gentle care and compassion, and his resilience in the face of adversity.”

Goldsmiths’ College music, dance and drama

The Freeman of Lewisham ceremony was followed by a celebratory programme of performance.

This included music composed by Goldsmiths’ Professor of Music Stanley Glasser, (1928-2018) The Drought, which had been commissioned by the local school Colfe’s for their tour of California.

The lyrics had been written in Southern Sotho by Goldsmiths’ BMus student Ndonda Khuze (1957-2017) who had grown up in one of South Africa’s Black Townships.

Increasing political frustration and police harassment had forced him to leave as he developed his career in creative and performing arts.

In exile, he co-founded the versatile ensemble Amandla that had toured throughout the world, appeared in concerts with major South African artists such as Miriam Makeba and Hugh Masekela, and worked on the music for the Oscar winning film Cry Freedom.

Professor Glasser had been born in South Africa, was passionately devoted to the country’s town and country folk music and credited it with being one of the dominant influences that forged his musical language and style.

The photograph also depicts the involvement of Goldsmiths’ Youth Orchestra that was run under the auspices of the College’s then Department of Continuing and Community Education.

Report on ceremony for Archbishop Desmond Tutu in Goldsmiths’ Hallmark magazine for staff and students.

All of the public record and reporting of this event was the work of Sue Boswell who edited and published Goldsmiths’ internal monthly printed magazine Hallmark and was assisted at the time by Sally Oliver.

Grove Park connections

The Times reported that Archbishop Tutu was also presented at the ceremony ‘with an illustrated scroll with pictures of St Augustine’s Church, Grove Park, south London, where he served as honorary curate between 1972 and 1975.’

His work for the Theological Education Fund (TEF) meant that he travelled widely from his family home in Lewisham and in 1972 witnessed Idi Amin’s expulsion of Ugandan Asians.

He experienced one of his only racist encounters in Britain when a stranger told him ‘You bastard, get back to Uganda,’ mistaking him for a Ugandan Asian refugee.

At the time he also acknowledged that he retained his own subconscious anti-black racist thoughts; when on a Nigerian plane, he felt a ‘nagging worry’ on discovering that both pilot and co-pilot were black.

He had realised he had been conditioned into thinking that only whites could be entrusted with the great skill and responsibility of piloting a plane with passengers.

The Grove Park Heritage and Character Assessment published in June 2016 would celebrate the area’s Desmond Tutu associations; particularly in Baring Road, the location of the Church and public parks.

The report recognised that ‘Grove Park accommodated one of its most famous residents […] when in 1972 Anglican Bishop and South African social rights activist Desmond Tutu moved into a home on Chinbrook Road where he lived for three years. […] In 2009, the Tutu Peace garden was opened.’

The idea for the peace garden

Opera Singer Suzannah Clarke discovered Archbishop Tutu had lived in her house in the 1970s.

She decided to invite him back to the house to see how the area had changed.

After contacting the South African embassy, she was astonished when the archbishop himself phoned her to accept her invitation to tea.

Suzannah told the BBC:

“After he accepted, I then realised that there was nothing to note that he had actually lived here for about 10 years in virtual exile, so I thought I would build him a commemorative peace garden. To begin with I was going to do it in my back garden but was thrilled that Lewisham Council offered us the park to build it in.”

The garden was designed by designer and TV presenter Chris Beardshaw and took him six weeks to complete.

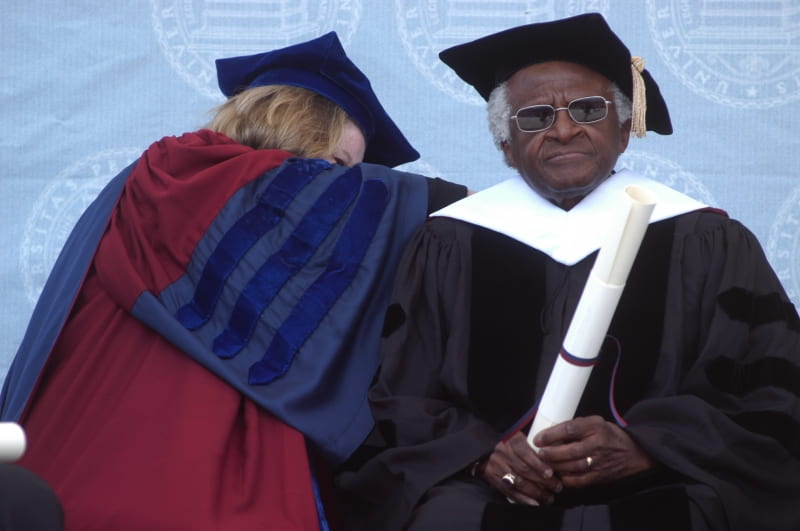

Desmond Tutu at the University of Pennsylvania in 2004. Image by Kyle Cassidy.CC BY 2.5

Chris Beardshaw said:

“This was a huge challenge as I wanted to create something which is aesthetically rewarding, of educational value, and will promote social interaction and harmony in the community. We aimed to create a model garden that could be developed further over years to come. Peace is the catalyst, not the end result.”

The Tutu Peace garden initiative was reported by the BBC in 2009 largely because Archbishop Desmond Tutu was so delighted to travel back to Britain to open it himself in another significant event honouring his work in peace and reconciliation.

Terry Waite CBE, who had been taken hostage himself when on a mission to Beirut to negotiate the release of people abducted during the Lebanese civil war, also spoke at the 60-minute ceremony.