Digital technology touches on and empowers every aspect of our lives, whether as consumers, users of public services, citizens or voters.

Yet the collection and exchange of personal information can interfere with our right to privacy, and the abuse of technology can distort our democracies and lead to serious breaches of human rights.

The informational privacy mega-scandals of recent years, such as the dramatic revelations by Edward Snowden of the post 9/11 global, mass, surveillance systems operated by security services, or the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data harvesting scandal, which were courageously brought to the surface through the work of Carole Cadwalladr and whistle-blower Chris Wilie, point, worryingly, to the rise of a new Panopticism that threatens to suppress private existence in the interest of security, financial gain and control of political power.

On November 5, the Goldsmiths Law symposium on technology and human rights, in collaboration with the Goldsmiths-based Knowing Our Rights project and the New Europeans thinktank, explored key questions around the difficult coexistence of technology with human rights.

Prof Dimitrios Giannoulopoulos, who holds Goldsmiths’ inaugural chair in Law, opened up the symposium by identifying four key preliminary lines of inquiry: (a) the regulation of state surveillance, and the importance of ECHR jurisprudence in striking the balance between protecting national security and the right to privacy; (b) the abuse of communications technology as a threat to democratic elections in the age of social media; (c) the human rights challenges posed by artificial intelligence and (d) the ethical objections to machines exercising control over humans, e.g. in border control situations (he mentioned the example of an EU funded project, called IBORDERCTRL: the project is developing a way to speed up traffic at the EU’s external borders and ramp up security using an automated border-control system that will put travellers to the test using lie-detecting avatars).

Prof Giannoulopoulos explained that the symposium aimed to undertake a contextual study of specific technologies’ impact on the right to privacy, and reflect on what specific measures we can take to protect our core individual liberties against technological threats, and conversely how we can use technology to enhance the enjoyment of individual liberties.

Prof Douwe Korff with Julie Ward MEP

Prof Douwe Korff (Emeritus Professor of International Law at London Metropolitan University, Associate of the Oxford Martin School, Oxford and Visiting Fellow at Yale University’s Information Society Project) explained that it is becoming clear that the problem is not the rules and guidelines, but how they are being applied, noting, with concern, that law enforcement agencies are increasingly demanding the powers of national security agencies. Referring to the ECHR, he also noted that fighting arbitrary power, including in relation to privacy, is at the very core of the Court’s jurisprudence, but the problem has always been the loopholes, those deriving from the antagonistic interest to protect national security or public order for instance.

Julie Ward MEP (who is Labour’s spokesperson in the European Parliament on culture and education, member of the women’s rights and gender equality committee, Board member of the European Internet Forum, Attendee of the annual Internet Governance Forum, and an expert of the Goldsmiths-based Britain in Europe thinktank) argued that legislators have been slow to respond to the issue of technology conflicting with human rights. “The Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandals demonstrate lack of attention”, she pointed out, “with Brexit and Trump being wake up calls”, adding that “there are dark web machinations we don’t even know about”.

Julie Ward MEP (who is Labour’s spokesperson in the European Parliament on culture and education, member of the women’s rights and gender equality committee, Board member of the European Internet Forum, Attendee of the annual Internet Governance Forum, and an expert of the Goldsmiths-based Britain in Europe thinktank) argued that legislators have been slow to respond to the issue of technology conflicting with human rights. “The Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandals demonstrate lack of attention”, she pointed out, “with Brexit and Trump being wake up calls”, adding that “there are dark web machinations we don’t even know about”.

Julie discussed her membership of the European Parliament Digital Working Group and the Human Rights Committee, and her work on the Copyright Directive, which she is a strong advocate for and which she considers an important mechanism to protect the incomes and incentives for creatives. She also raised concerns that at the European Internet Forum, “civil society is hardly in the room”, and that it’s primarily the “big players” (tech companies) talking to governments. Julie pointed to the importance of ensuring that access to the internet is protected as a human right, and expressed concern that post-Brexit, British politicians will “not be in the room” when internet-related agreements are being made and Britain will have less global influence in this debate.

Andreas Aktoudianakis with Prof Dimitrios Giannoulopoulos

Andreas Aktoudianakis, who provides direct, high-level research and programmatic support to the director of the Open Society European Policy Institute, placed the question in the context of the rise in populism in Europe. Big data is generating a ‘modern revival’ of 1930s communication theories, he explained, with algorithms confirming existing biases (filter bubbles) and falsehoods being 70% more likely to be shared than truths.

Dr Bethany Shiner

Bethany Shiner, a lecturer in Law at Middlesex University, asked whether the electoral law’s understanding of influence for the purpose of democratic autonomy is out-of-date when it comes to technology. She argued that explanations for electorate decision-making and influence, as reflected in popular discourse, as well as the law, are flawed and problematic in their simplicity, and that instead of measuring interference in elections through undue influence, harm can be shown by focusing on the intent of political campaigns to knowingly deceive, mislead or lie.

Hannah Couchman, who leads Liberty’s advocacy work on technology and human rights, including surveillance, the use of technology in policing and data rights, expressed significant concern about the use of AI in police decision-making and predictions. Datasets are all intrinsically biased, she noted; when we teach a computer, we are teaching it our own biases. She raised the example of HART (Hart Assessment Risk Tool), used by Durham Police Constabulary, which diverts people to and from the court process depending on their data and ‘risk of re-offending’. Hannah expressed the wider concern that these technologies are being used before we really know how they work; advantages are actually irrelevant until we’ve addressed the human rights implications of these technologies.

Hannah Couchman with Goldsmiths’ Prof Susan Schuppli

The use of AI in policing in particular could generate arbitrariness, inequality and breach of fundamental rights, Hannah observed. The foundation of democracy and the rule of law is that you have reasoned decisions, which somebody can challenge and question and appeal, she concluded. You can’t do that with an algorithm, and, with self-learning algorithms you can’t even do that with the designer of the algorithm because they themselves will no longer be able to explain it.

Dr Jerdrez Nicklas

Dr Jedrzej Niklas, a Research officer in the department of Media and Communications for the Justice, Equity and Technology (JET) project, at the London School of Economics, focused on the relationship between AI and social justice, explaining how JET examines the impact of automated computer systems on anti-discrimination advocacy and service organizations in Europe. Of particular interest to the symposium was a discussion of gender bias in search engines, which Jerdrzej explored in the Q & A session that followed his presentation.

Midori Takenake

Midori Takenake, an associate at Clifford Chance, working in the Corporate Technology team and advising a wide range of corporates, financial institutions and technology companies on data protection, emerging technology and key commercial agreements, explained that as a result of the GDPR, companies are now taking more notice of their ethical use of AI and large datasets. Companies are so worried of the fines attached to the GDPR that people are actually paying attention to these issues in the boardroom. “Data ethics” is the new buzzword, she said. But, at the same time, it’s often overlooked that GDPR and data protection is actually just one part of a much larger, broader ‘umbrella’ issue: human rights; the link is there but often is not made explicitly.

Kilian Vieth

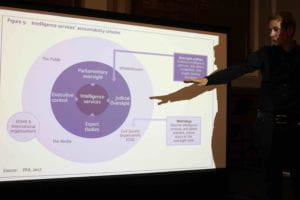

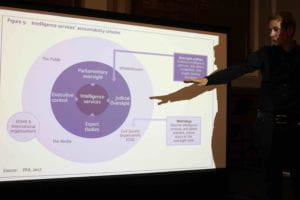

Kilian Vieth, who manages the work of SNV (Stiftung Neue Verantwortungon) on government surveillance and intelligence oversight, focused on how judicial oversight is critical in the field of bulk surveillance, but also a very complex exercise, because of the different conceptualisations of the intelligence cycle.

Jonathan McCully

Jonathan McCully, a legal adviser to the Digital Freedom Fund and Editor of Columbia University’s Freedom of Expression Case Law Database, discussed facial recognition technologies, giving the example of taking a biometric map of your face and placing it on a watch list. The facial map can then be used to identify individuals in crowds and other public places. This generated significant concerns in relation to the discriminatory effects of these practices, particularly for women and people of colour. He also referred to the challenge of regulating the “Internet of Things” and the “Internet of Toys”, which he described as “bringing spies into our homes”. He pointed to the example of the “My Friend Caila” doll which has been banned in many places due to spying concerns.

from left to right: Jonathan McCully, Sabrina Rau and Kilian Vieth

Sabrina Rau, a Senior Research officer at the Human Rights, Big Data and Technology project (HRBDT) at the University of Essex, focusing specifically on the regulation of businesses, provided a brief background on the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and their development, explaining what they mean for ICT companies in the context of current regulation and what unique elements of the sector make such assessments challenging. She concluded by illustrating the added value of consulting the UNGPs to determine the responsibility that ICT companies should have when it comes to protecting, respecting and remedying human rights.

Griff Ferris, who is Legal & Policy Officer at Big Brother Watch, gave an outline of the Big Brother Watch (and others) v the United Kingdom case at the European Court of Human Rights, brought post-Snowden in 2013/14. He described the chilling effect of the PRISM and Tempora bulk interception regimes that were adopted by NSA and GCHQ, and were at the centre of the Big Brother Watch case. The outcome of the case was that the Court agreed that there was a lack of oversight and a lack of safeguards, he explained, but that generally the concept of bulk surveillance did fall under the state’s margin of appreciation (and was therefore legal). He concluded his analysis on the case by noting that Big Brother Watch is continuing to call for respecting necessity and proportionality in bulk surveillance.

He then added that other areas of concern for Big Brother Watch include face surveillance, predictive policing, free speech online, restrictions in relation to the regulation of the internet and the use of digital evidence in relation to victims with a complete lack of safeguards in place (e.g. rape victims’ phone data being downloaded by the police etc.)

Marianne Franklin, Professor of Global Media and Politics at Goldsmiths, who intervened via Skype, offered an overview of the Internet & Rights Principles Coalition, where she has served as a co-chair. The coalition is active across internet policy-making meetings that focus on human rights frameworks with partipcipants from civil society, technical community, academia, business, IGOs, political parties, and other policy makers around the world. It provides leadership and supporting roles on the ground and online for education, consultations, and implementation projects in which rights-based and sustainable internet policy agendas are at stake.

The main work of the Coalition has been to build awareness, understanding and a shared platform for mobilisation around rights and principles for the internet, explained Prof Franklin, drawing on the Coalition’s flagship document, the Charter of Human Rights and Principles for the Internet.

The symposium closed with a presentation by Christina Varvia, deputy director at Forensic Architecture (FA), the pioneering research agency based at Goldsmiths. Christina explained how FA undertake advanced architectural and media research on behalf of international prosecutors, human rights organisations and political and environmental justice groups. The premise of FA is that analysing violations of human rights and international humanitarian law (IHL) in urban, media-rich environments requires modelling dynamic events as they unfold in space and time, creating navigable 3D models of sites of conflict and the creation of animations and interactive cartographies on the urban or architectural scale. The techniques of architectural analysis also enable FA to generate new insights into the context and conduct of urban conflict. Combining these novel approaches, FA have built a track record of decisive contributions to high-profile human rights investigations, providing forms of evidence that other methods cannot engage with.

The symposium was organised in collaboration with the New Europeans thinktank, and special thanks are due to Roger Casale, CEO of New Europeans, and Kristiana Kuneva, for coordination and support. New Europeans champions freedom of movement, non-discrimination and the principle of solidarity in Europe.

The team behind the Law programme at Goldsmiths wants to thank the many sixth form students who have attended the symposium for their attention as well as the wider audience which engaged in the debate, including representatives from the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL) and the Joint Committee on Human Rights.

The team behind the Law programme at Goldsmiths wants to thank the many sixth form students who have attended the symposium for their attention as well as the wider audience which engaged in the debate, including representatives from the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL) and the Joint Committee on Human Rights.

Special thanks are also due to Gemma McNeil-Walsh, Research Assistant to the Director at BIICL. This post is based on notes she has taken at the symposium.

Photographs were taken by, and are the copyright of, of Richard Gardner.

For more information on the above, and on how the LLB Law programme at Goldsmiths integrates theoretical knowledge and skills related to the interaction between law, technology and human rights, please contact Prof Dimitrios Giannoulopoulos.

Julie Ward MEP (who is Labour’s spokesperson in the European Parliament on culture and education, member of the women’s rights and gender equality committee, Board member of the European Internet Forum, Attendee of the annual Internet Governance Forum, and an expert of the Goldsmiths-based

Julie Ward MEP (who is Labour’s spokesperson in the European Parliament on culture and education, member of the women’s rights and gender equality committee, Board member of the European Internet Forum, Attendee of the annual Internet Governance Forum, and an expert of the Goldsmiths-based

The team behind the Law programme at Goldsmiths wants to thank the many sixth form students who have attended the symposium for their attention as well as the wider audience which engaged in the debate, including representatives from the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL) and the Joint Committee on Human Rights.

The team behind the Law programme at Goldsmiths wants to thank the many sixth form students who have attended the symposium for their attention as well as the wider audience which engaged in the debate, including representatives from the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL) and the Joint Committee on Human Rights.