Dr Laura Crane completed her undergraduate and postgraduate (MSc and PhD) degrees within the Department of Psychology at Goldsmiths. Laura now works as a Postdoctoral Research Associate and Associate Lecturer within the Department. She is also an Honorary Lecturer at UCL’s Institute of Education, and a Research Fellow at City University London.

Dr Laura Crane completed her undergraduate and postgraduate (MSc and PhD) degrees within the Department of Psychology at Goldsmiths. Laura now works as a Postdoctoral Research Associate and Associate Lecturer within the Department. She is also an Honorary Lecturer at UCL’s Institute of Education, and a Research Fellow at City University London.

Here she talks about what it means to participate in research.

Recently, I was invited to an event on autism and the criminal justice system (my area of expertise). The delegate list was impressive, including academics, legal professionals and charity representatives (all with extensive experience in the area). The day was interesting and varied. At one particular point in the day, the delegates were asked to work in groups to identify the issues faced by autistic people[1] when encountering the criminal justice system, as well as some potential solutions to these issues. Each group was busy generating ideas, before I raised what I thought was a very obvious question: ‘If we want to know what the issues people with autism face in the criminal justice system, shouldn’t we start by involving them in these discussions?’

In our inaugural blog post, Prof. Andy Bremner (our Head of Department) discussed how ‘working together is welcome’ at Goldsmiths. Indeed, working together is welcome, and commonplace…amongst academics. I should stress that one of the strengths of Goldsmiths’ Psychology Department is that there are several examples of academics working collaboratively with non-academic stakeholders (e.g., police officers, musicians). However, in this blog post I want to question whether we are really doing all we can to engage the communities that we study in our research.

A few years ago, Pellicano, Dinsmore and Charman (2013) published a thought provoking paper on researcher-community engagement in autism. They conducted a survey of over 1500 stakeholders interested in autism research – gathering the views and opinions of researchers, professionals (e.g., teachers, therapists), and the autism community (autistic people and their families). The results revealed that whilst researchers perceived themselves as engaged with the autism community (in terms of dissemination, dialogue and research partnerships), autism community members did not share this view. In addition, whilst professionals were fairly satisfied with their involvement in research, those on the autism spectrum and their families were not.

Following up these survey results with focus groups and interviews, Pellicano et al. (2013) highlighted the variable nature of autistic community involvement in research. For example, autism community members expressed dismay about giving up their time to take part in research but not finding out the outcomes, with one participant commenting: “they only want us as guinea pigs”. Further, community members felt that their contributions were not valued by researchers, and they expressed scepticism about whether their views would have any influence on future research or policy.

These issues are not unique to the field of autism. From recent discussions with colleagues, they also apply to work in other neurodevelopmental conditions (e.g., Developmental Coordination Disorder), as well as psychology more broadly. Nevertheless, there have been several examples of successful researcher-community partnerships in some research areas, particularly in the field of learning disabilities (e.g., Powers et al., 2007; Richardson, 2000). ‘Participatory research’, as it is termed, also forms the basis of ‘INVOLVE’ – a government-funded programme aiming to advance public involvement in research, in order to make it an ‘essential’ part of the way in which research priorities are identified, and the way in which research is designed, conducted, and disseminated.

But how does participatory research work?

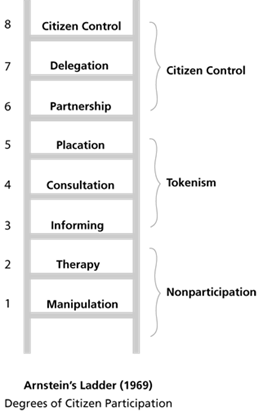

There are several different ways in which stakeholders can be involved in the research process, and these are highlighted in Arnstein’s (1969) ladder of citizen participation. Arnstein notes that the bottom rungs of the ladder describe levels of ‘non-participation’, in which researchers have control over the participants in the study. This tends to be the kind of involvement that is commonplace in psychology research studies with clinical groups (e.g., people with autism). Further up the ladder are varying degrees of ‘tokenism’, in which the participant is given a voice but they are not conferred any power over the research (and there is no change in the status quo). There has been a move towards this kind of participation in recent years, especially in terms of ‘informing’ participants about research findings; for example, researchers are encouraged to disseminate their findings in outlets for non-academic audiences (e.g., The Conversation), and many academic journals (e.g., Autism) require authors to produce easy-read summaries of research findings to accompany their articles. Moving even further up the ladder, community members can engage in research partnerships, or even have control over the research process (i.e., having managerial power, or holding the majority of decision-making roles) – these are referred to as instances of ‘citizen control’. However, these tend to be relatively rare occurrences.

There are several benefits to adopting a ‘participatory’ research design and involving stakeholders in the research process. For example, it ensures that the research priorities are valuable and have a genuine impact on the lives of the people being studied. In addition, the involvement of community members is likely to aid the recruitment of participants and in subsequent dissemination activities. Community involvement would also provide important insights into the area under study (perhaps ones that are overlooked by researchers who do not have this ‘insider’ knowledge).

Despite my enthusiasm for participatory research, I openly acknowledge that the majority of my current and previous research projects (on autism in the criminal justice system, as well as autism diagnosis) have been researcher-led. Although my work is often conducted in collaboration with professionals (e.g., police officers, clinicians), the involvement of community members has tended to be limited to the bottom or middle rungs of the ladder. This is because participatory design is not without its challenges, such as the additional time and effort (and often funding) required to engage in researcher-community partnerships (Pellicano et al., 2013), along with the lack of training opportunities available for early career researchers (during my seven years of study within Goldsmiths’ Psychology Department, I wasn’t even informed of participatory research, yet alone had any opportunities for training!). As proud as I may be of the research projects I’ve been involved in, and the outcomes of that work, I wholeheartedly feel they could have been improved with greater community input and involvement.

The research projects I’m developing at the moment have a much greater focus on collaboration with community members and I’m really excited to see how they progress. For example, I’m about to begin an evaluation of an autistic-led post-diagnostic support programme, in collaboration with the (autistic) developer of the programme. We’ve jointly decided on the focus of the research, and will be working together throughout to achieve the aims of the evaluation.

Partnerships like this take time to come to fruition, and I’m particularly struggling to ‘move up the ladder’ for areas in which I’m only just starting to conduct research (e.g., Developmental Coordination Disorder). However, I hope this blog post encourages researchers (and students) to reflect on the involvement of the communities they study in their work, and to consider how they might start working their way further up the rungs.

Laura is on Twitter : @lauramaycrane @GoldActionLab

………………….

[1] There is a debate regarding the most appropriate way to refer to individuals on the autism spectrum. Whilst person-first language (i.e., ‘person with autism’) has typically been advocated, many autistic individuals prefer disability-first language (i.e., ‘autistic person’). Throughout this blog post, both terms are used, to respect this diversity of views (see Kenny, Hattersley, Molins, Buckley, Povey & Pellicano, 2015, for further discussion of such issues).