MA International Relations student, Sumiré Jay, joined the Kachin Revolution day celebrations in West London, diving into an incredible evening of speeches, songs, presentations, and prayer.

Hounslow, West London, may not be the first place you would imagine encountering the celebrations of a South-east Asian revolution. Yet it was here that, on 5 February, a group of about 25 men, women, and children gathered for the 58th anniversary of Kachin Revolution Day. Representatives from the Kachin diaspora community across London commemorated one of longest ongoing armed insurrections: the Kachin Rebellion in Myanmar. My classmates and I joined the celebrations to learn about the politics of conflict-induced diasporas in a course on Armed Politics and Political Violence. Together we dived into an incredible evening of speeches, songs, presentations and prayer (Kachin are predominately Christians, although Myanmar is a Buddhist majority country) as well as informal conversations over food and coffee.

Group photo in Hounslow. Pic: Kachin National Organisation

The Kachin people are one of the 135 officially recognised ethnic groups in Myanmar. But name recognition does not come with minority rights and political voice. Myanmar, or Burma (Myanmar is the name imposed by the military dictatorship and eschewed by many regime critics, especially ethnic minorities), has been plagued with ethnic conflict since its 1948 independence, and even before. Both of the country’s names come from the leading and dominant ethnic group in the region, the Burmans (also called Bamar), who make up about 60% of the country’s citizens, and historically have lived in the valley and delta of the Irrawaddy River.

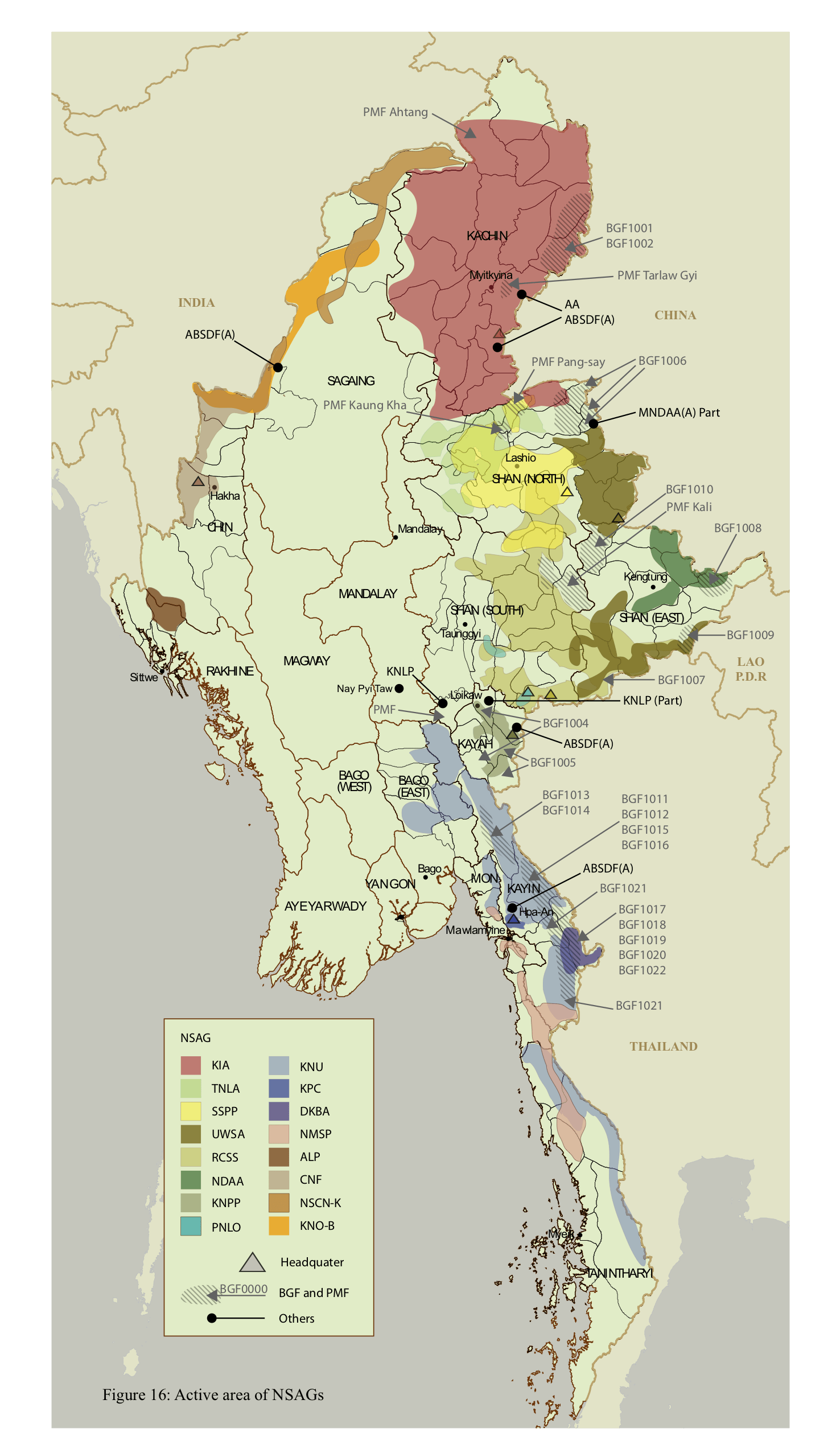

Active areas of ethnic non-state armed groups (NSAGs). Source: Burma News International.Burma suffered under colonial rule, and was a British colony from 1824 until 1948, with most of the 19th century seeing Burma ruled as part of the British Raj. As so often this created the seeds of ethnic conflict in the country. Similar to other contexts, the British Empire recruited ethnic minorities into its security apparatus to oppress the rising nationalism of the Burman majority and prevent a united front between different ethnic communities. In the Second World War, Burma was a hotspot of conflict between Japanese and Allied forces. Many Burman civilians and soldiers initially supported the Japanese thinking they would aid them to gain independence from the British. However, nearly all ethnic minorities maintained their support for the British seeing them as a guarantor of minority rights. The war thus further positioned ethnic communities against each other.

After the Second World War ended Burma Independence Army leader General Aung San (the father of Aung San Suu Kyi) negotiated the Panglong Agreement with leaders from the ethnic minorities. This agreement served as the basis for Burma’s independence as a federal union with provisions for significant autonomy and minority rights for the country’s ethnic nationalities. However, Aung San was assassinated by political rivals before independence. The Panglong Agreement was never enacted and civil war broke out between the Burman leaders and minorities throughout the newly formed country. It did not take long for ideas of federalism to give way to dreams of independence for many ethnic minorities, including the Kachin. When General Ne Win assumed power in a coup- d’état himself to power in 1962, Kachin revolutionaries formed the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO) and started their rebellion against the state. Civil war and military rule have persisted since. While the military officially stepped down from government in 2011, the conflict has worsened for ethnic minority communities on the northern border to China. This was particularly so after a long ceasefire between the KIO and the military broke down in 2011. Between 2011 and 2015, up to 100 000 Kachin civilians (one tenth of the Kachin population) have been displaced by heavy fighting. Since long-term democracy idol Aung San Suu Kyi came to power, the military’s offensives against Kachin forces and rebels from other ethnic minorities have only increased. This has tarnished the reputation of Suu Kyi amongst the Kachin people, who have traditionally supported, including in the 2015 national elections.

Kachin frontline soldier in Myanmar. Pic: David Brenner

Back in Hounslow at the Kachin Revolution Day commemorations, Suu Kyi’s fall from grace was a hotly discussed topic. In fact, from the perspective of Kachin freedom fighters and independence activists many preconceived wisdoms about Myanmar and its political transition look different to the mainstream media. For instance, many Kachin have become wary of ceasefires and peace talks. While counter-intuitively at first, listening to their own accounts is insightful. The KIO indeed attempted to negotiate peace during a long ceasefire with the government between 1994 and 2011. In Hounslow, I learned that the ceasefire and peace process was however riddled with flaws. While the government offered economic benefits to Kachin leaders, it did not make any political concessions addressing the root cause of the conflict: ethnic oppression and demands for political autonomy. On the contrary, the government has maintained a dismissive, somewhat condescending stance of telling minorities to simply trust the government to act on their behalf while continuing to abuse its power. This has furthered the Kachin aspirations towards an independent state.

As Kachin people in Myanmar struggle against the repressions by the national government, diaspora groups play an important role in mobilising for the Kachin Revolution. In the wake of the Kachin ceasefire, exile Kachin revolutionaries founded the Kachin National Organisation (KNO). Organised as the KNO the small Kachin diaspora in London focuses on lobbying the UK government, as do other KNO branches in their respective host countries. The Kachin diaspora also organised the Kachin Relief Fund, a humanitarian organisation that raises support for displaced Kachin. The work of the relief fund is particularly important because many displaced civilians in the war zones of northern Myanmar are located in areas where the Myanmar government prohibits official aid organisations to operate. The Kachin Relief Fund mobilises its transnational networks and expertise for delivering aid to otherwise unreachable communities.

While learning about the complex politics of ethnic conflict in Myanmar and diaspora activism in London, the Kachin Revolution Day also gave me intimate insights into the lives of Kachin refugees in the UK and provided a human face to the idea of armed resistance. When we arrived at the event, held in the function room of an unassuming business hotel, we were welcomed immediately as if long-lost, prodigal members of the Kachin community. A little girl, dressed in a traditional Kachin outfit and a beautiful shawl of silver bells, ran up to us and pressed loose sheets of paper into our hands, onto which the words (and English translations) of revolutionary songs and chants were printed. Other kids ran around offering high fives and huge smiles. We were introduced to Htang, the foreign affairs spokesperson of the KNO. Htang is a soft-spoken woman who smiles a lot. Her happy and gentle appearance is not quite how I imagined a revolutionary from Myanmar. Htang was born in Lashio a traditional stronghold of the Kachin rebellion and hotspot of the civil war in Myanmar. She came to London as a refugee but her life remained intimately entangled with the politics of war, violence and suffering in her home where many of her family member remain.

Festivities at the Kachin Revolution Day. Pic: Sumiré Jay

For the remainder of the evening, Htang acted as a translator for our group, sitting among us and live-translating the words of the speakers and presentations from Kachin to English. The ceremonial leaders started with commemorating the uncountable martyrs fallen over the decades of armed struggle in the Kachin hills. Speakers then went on to tell about recent conflict dynamics in Myanmar, activities of the KNO worldwide and the Kachin community in London. At one point a speaker wearing Maoist-inspired uniform hat and the red and green colours of the Kachin revolution took out a guitar and performed a revolutionary song for everyone. After the conclusion of the official event, there was a Kachin dish of chicken and noodles, and many of the organisers and speakers mingled over coffee, giving us an opportunity to ask questions and learn more about the Kachin people, their fight for independence, and the state of political affairs across Myanmar.

My overwhelming impression after the event was of the openness, friendliness, and community spirit among the Kachin diaspora community. Having arrived with a limited background of Burmese politics and ethnic conflicts, the community opened their arms to us and welcomed us in, happy to answer any questions about Kachin, Myanmar, or simply to philosophise together on the state of the world in February 2019. Attending the Kachin Revolution Day celebration was a great honour, and I thank the members and organisers who made this possible. I sympathise with your struggle: ‘Awng dawm! Towards independence!’Kai

Htang Lashi from the KNO will reflect on the Kachin Rebellion in Myanmar from an insider’s perspective as part of the event series Understanding Armed Resistance, hosted at Goldsmiths (Room LG01, PSH) by the Centre for Postcolonial Studies, on 5 March, 17:30-19:00 in LG01 PSH. You can register on the eventbrite page.

For more information on the MA International Relations, visit the programme page on the Goldsmiths website.

This story was also published in Goldsmiths student magazine, [Smiths].