Glitch Feminism proposes that an error in a social system is a moment for revisioning and change. ‘This glitch is a correction to the “machine”, and, in turn, a positive departure.’ (Russell, 2012). Transposing this idea to archives: if the social system is the institution and the glitch is its forced closure during the pandemic, how can we use this moment to reassess our work? Libraries and archives often attract audiences with high levels of cultural capital; the ‘glitch’ in normal operations invites us to consider who is not present and how this can be addressed. As the Women’s Art Library was not able to invite guests in, the question of how to take the experience out was timely.

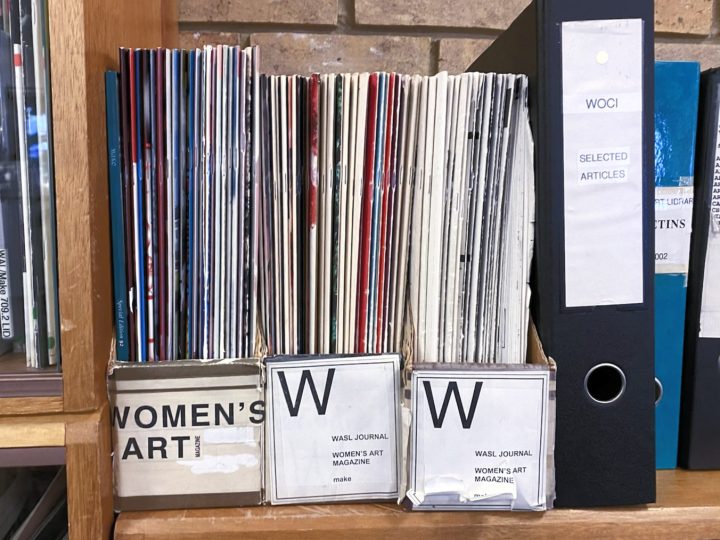

In late 2020, the Women’s Art Library (WAL) awarded me the Art in the Archive Bursary. My artistic practice is focused on listening, considering sound as a way of knowing. Though archives are predictably quiet spaces, I could imagine voices speaking from within the boxes. As a first-timer at WAL, I was keen to work with others to explore the materials together and to learn more about the archive through the diversity of our hearings. I wrote to community organisations operating within 10 miles of the WAL – organisations supporting elders, carers, migrants, families, young people and other groups. I asked how their members are able to engage with projects during lockdown, noting different access needs. There was no single way that worked for everyone, so flexibility was crucial for the project. Community organisations sent my invitation to explore the WAL out to their members; nine women got in touch.

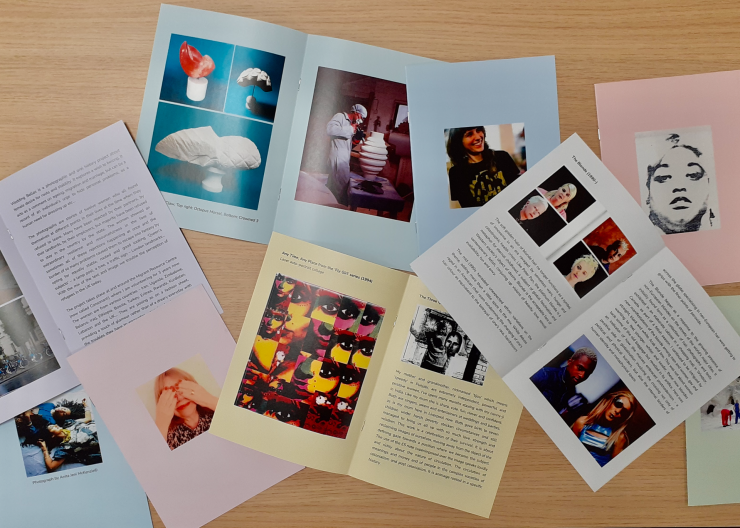

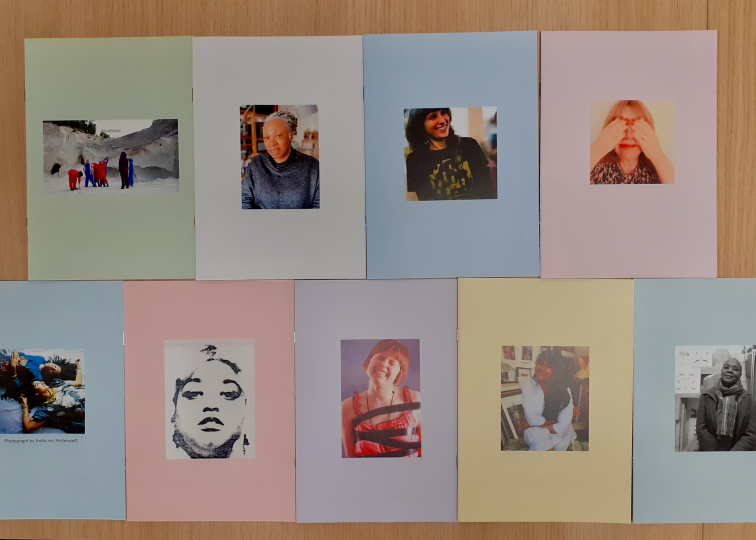

As access to the library was limited during lockdown, the WAL curator Althea Greenan provided me with scans of archive materials, which I supplemented with related images and texts I found online. I organised these materials into (initially digital) packs, each relating to the work of one artist whose work is held in the collection. The materials included press releases, invitations to private views, newspaper clippings and photographs of the artist and their work. I was keen for each pack to have some common materials, including a photograph of the artist and their biography. I also selected images of their work and contextual writing about it. This was hard to find in some cases – the Women’s Art Library was founded in the early 1980s in response to the lack of documentation of the work of women artists, before our lives were archived on the internet.

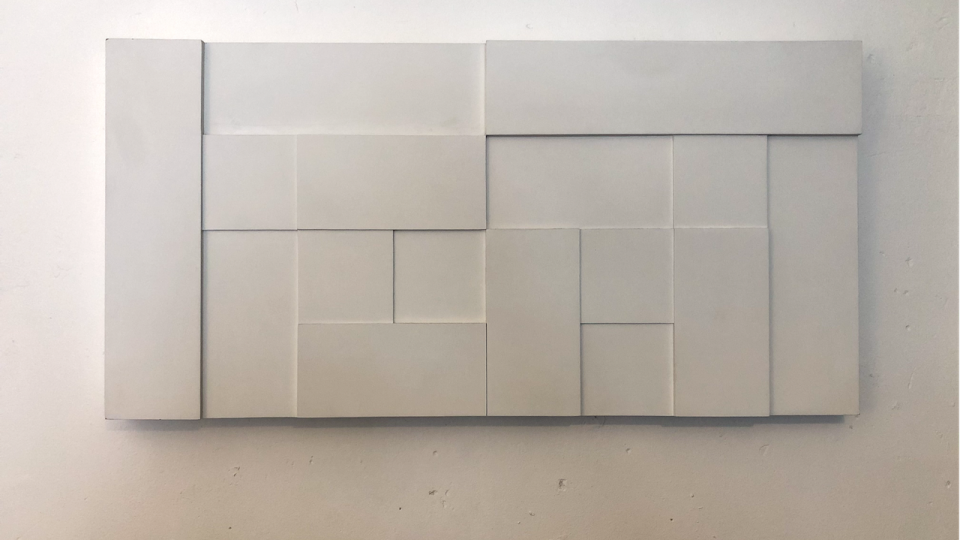

I wondered about my search for materials that provide ‘context’ in relation to the archive. Would it be OK to send a local resident a picture of an artwork from the archive on its own? Perhaps this would create an openness, freedom for the participant to have their own experience without sifting through layers of existing interpretations and ascribed meanings. On the other hand, would this appear obtuse; would it lack an entry point or frame through which to formulate a response? Digging deeper, the photograph of the artwork is not the artwork. How does the experience change when looking at representations of art, rather than the art itself? What is the experience of looking at archived ephemera from exhibitions, when the exhibitions are over and the artworks are elsewhere?

Ten packs of materials, each relating to one artist, resulted from my work with Althea. I printed these and sent a pack to each community participant via post or email, with an invitation to meet me online, on the phone, or on a park bench to explore it together. My first trip was to the Co-oPepys Community Arts Project in Deptford. There I met Luciana, Limor and Mila, all artists, who worked under the collaborative ‘We Women’ banner. We spoke about some of the artists in the packs. I asked them if they connected to the artists’ works, and if they had a favourite. I was struck by how freely they connected their personal experiences to the subject matter of the artworks. Personal stories were shared and recorded. Their responses were generous and they engaged deeply with the ideas present in the archive materials – they agreed that talking about what we could see helped to build meaning. I had a similar experience meeting Lucy and Laura on a park bench in Peckham, they intuitively linked their personal histories with their chosen artworks. Beatriz recorded her responses on voice notes and emailed them to me. She explored several artists’ packs before selecting an artist she shared cultural heritage with and spoke about her feelings of crossing multiple cultures. Finally, I arranged two sessions with members of Meet Me, a social and creative programme for over 60s in Lewisham. Rosaline, Moira and Dahlia have minimal access to digital technologies, so we arranged a group phone call linking up landlines to speak together. Conversations were lively and Dahlia’s laughter was a bright spot of the project.

The simple act of arranging conversations between people new to the archive opened a space for connection that deepened curiosity about the archive. We took on the voices we thought we heard in the archive as we exchanged our interpretations of the materials. These recorded encounters were endlessly rich. Seven hours of women’s voices responding to documentation of women’s artworks. To extend the invitation to new sections of the community, I edited the collected recordings together and submitted this as sound work Voicing the Archive for broadcast on local London community radio station Resonance FM. I hope the warmth of the voices within will act as a calling card, a heartfelt welcome to the archive.

The spirit of community, creativity and conviviality that comes from collective working really came across. This was what felt missing from our institutions as doors were shut during the pandemic, but also this is what feels increasingly rare and squeezed out as austerity cuts public engagement programmes. Only one of these nine women living within ten miles of the Women’s Art Library had visited the archive before. Given that funding for outreach projects is unlikely to increase in the current political climate, what are our options to share the resources we have outwards? In this collaboration with the Women’s Art Library, I prioritised hyperlocal connections and the production of creative takeaways for communities near to the WAL. As the project ended, I produced a series of simple zines providing an introduction to the WAL and an artist represented within. These zines will be posted to community organisations operating locally, and I hope that these small snippets of the archive end up in jacket pockets across the borough.

Hannah Kemp-Welch was recipient of the Art in the Archive Bursary 2020, funded by the Women’s Art Library and Feminist Review. Hannah is a sound artist with a socially-engaged practice. She produces audio works with community groups for installation and broadcast, using voices, field recordings and found sounds.

To visit the Women’s Art Library and access the zines printed as part of this project, please email special.collections (@gold.ac.uk) or phone Special Collections 020 7717 2295 to make an appointment. Visit the Special Collections page for further information about access and related collections or email Althea Greenan a.greenan(@gold.ac.uk) with more detailed queries relating to the Women’s Art Library.

References

Russell, L. (2012) Digital dualism and the glitch feminism manifesto. The Society Pages, 10.

Listen to ‘Voicing the Archive’, an audio artwork by Hannah Kemp-Welch