This workshop, organised by Beth Bramich and Hatty Nestor and led by the two co-founders of The Art of Captioning, Hannah Wallis and Sarah Hayden, aimed to introduce PhD researchers and others to a range of creative approaches to captioning, exploring what this can bring to working with art and activist archives.

The Art of Captioning is a British Art Network research group that brings together artists, curators, researchers, activists and access workers to address the state of captioning and access awareness in British Art. This workshop began with a presentation about The Art of Captioning’s ongoing work on access as ethos, which was available for participants to join remotely as well as in-person at 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning, Brixton. Below is a recording of Hannah and Sarah’s presentation introduced by Catherine Grant and live-captioned in the gallery by Kate, a stenographer who works for the company 121 Captions.

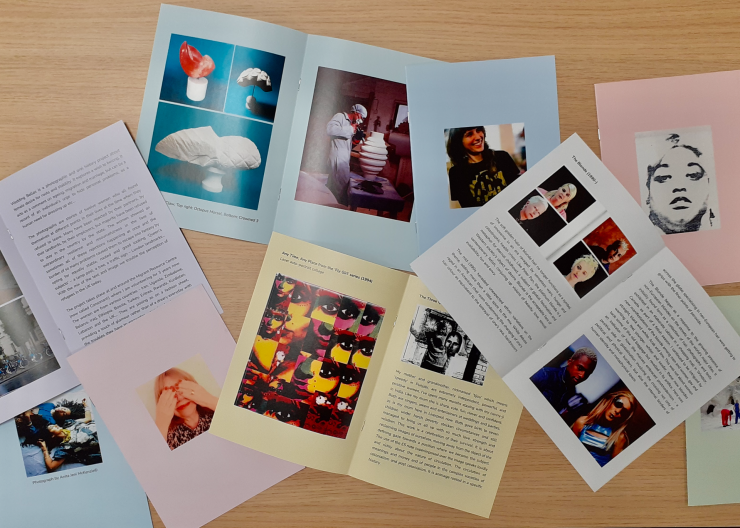

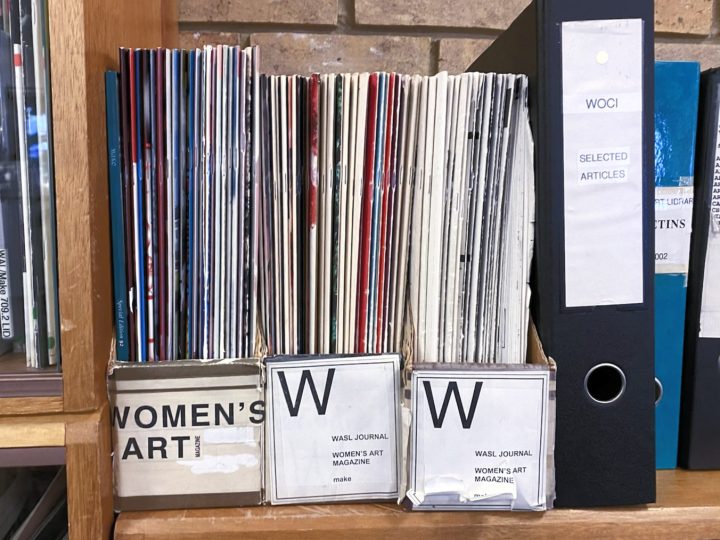

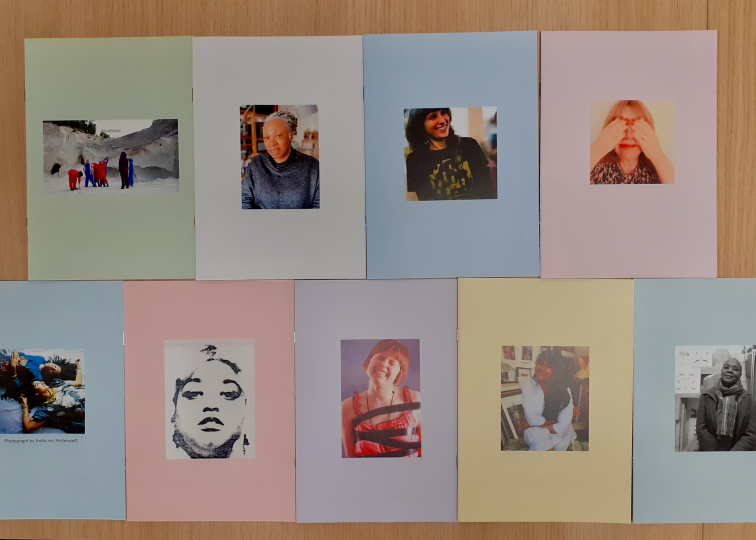

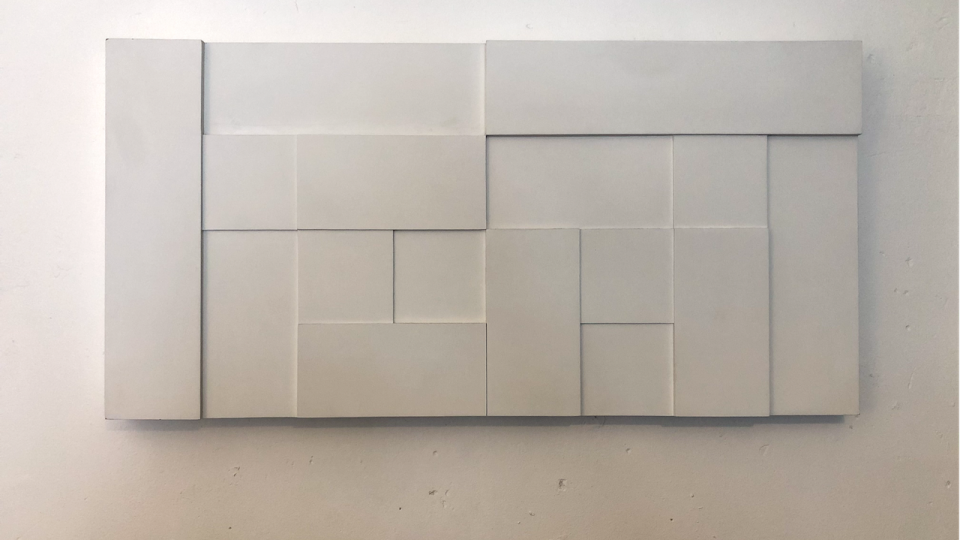

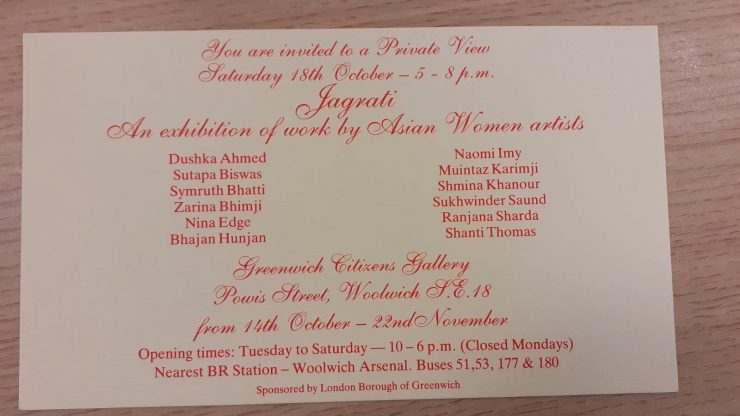

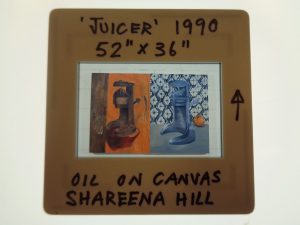

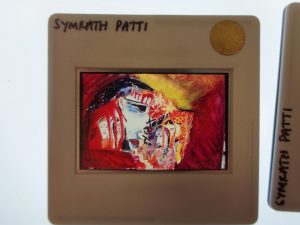

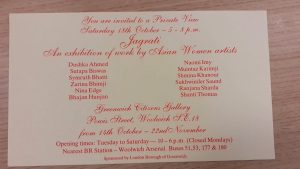

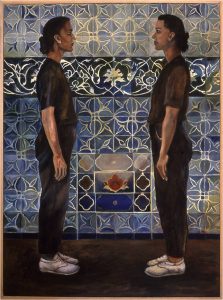

This presentation was followed by an in-person workshop at 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning, during which Sarah and Hannah led the participants in a series of activities looking at material from the Women’s Art Library collections, including a selection of ephemera from artists’ projects, audio tapes of interviews and talks, an artist’s film on DVD, and posters advertising various events and activities.

Recommended Resources

Hannah and Sarah compiled a few resources that they recommend for approaching accessibility.

Perkins Learning has produced a short clear guide to writing alt-text and image descriptions. This is endorsed by Rooted in Rights, a disability rights programme based in Washington State, USA.

A more expansive, but still eminently teachable approach is offered by Alt-Text as Poetry a collaboration between Bojana Coklyat and Shannon Finnegan, supported by Eyebeam and the Disability Visibility Project.

Further reading suggestions include Carolyn Lazard’s Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice and Rooted in Rights’ Accessibility Resources.

To learn more about The Art of Captioning please see their research group page on the British Art Network website.

FURTHER INFORMATION:

The Art of Captioning is a research group co-led by Hannah Wallis (Artist and Curator; Assistant Curator, Wysing Arts Centre) and Sarah Hayden (Associate Professor in Literature and Culture, University of Southampton, AHRC Innovation Fellow: Voices in the Gallery) that explores what creative captioning can bring to art while advancing vital work around access, equality and inclusivity in the sector. The aim of the research group is to bring together artists, curators, researchers, activists and access workers to address the state of captioning and access awareness in British Art, and builds on Wallis and Hayden’s previous programme, Caption-Conscious Ecology, at Nottingham Contemporary in 2021.

198 Contemporary Arts and Learning is a centre for visual arts, education and creative enterprise. Their work is framed by their local communities and the history of the Brixton uprisings; informed by a policy context that calls for greater action on equality, and shaped by unfulfilled demand for diverse visual arts and new pathways to creative careers.

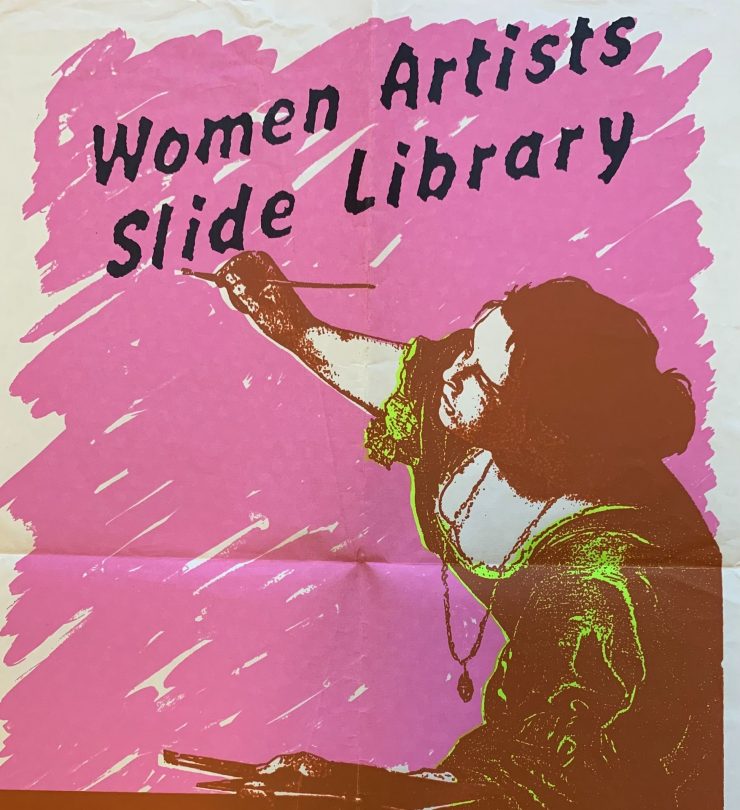

The Women’s Art Library began as the Women Artists Slide Library, an artists’ initiative that developed into an arts organization publishing catalogues and books as well as a magazine from early 1983 to 2002. WAL collected slides, ephemera and other art documentation from artists and actively documented exhibitions and historical collections to offer a public space to view and experience women’s art. As part of Goldsmiths Library Special Collections and Archives, the Women’s Art Library continues to collect, with thousands of artists from around the world are represented in some form in this collection.

This workshop was generously funded by CHASE Doctoral Partnership.