For the first Animating Archives workshop, Dr Althea Greenan, curator of the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, University of London, gave a tour through her own doctoral research on the slide collection, as well as the many creative responses to the archive by artists, contextualised with a history of the Women’s Art Library as it grew from home-based collection, through to a membership organisation, and finally to a university archive. The recording of Althea’s presentation can be found here:

Shadow Archives: a series of reflections and digital objects by the workshop participants

Workshop participants then shared their digital objects, which they had been invited to bring along. We didn’t record the discussion that took place as part of this workshop, but instead circulated an invitation to workshop participants to contribute their thoughts in this collective written post.

The discussion following Althea’s presentation opened up the topic of “Animating Archives” beyond what the organisers had imagined. Starting what might be seen as ‘authorised’ ways of bringing an archive to life – either by writing or various forms of art practice – the discussion moved to think about the digital production and circulation of archival material that then in turn might be thought as constituting a kind of shadow archive.

This was imagined in two ways: first thinking about the circulation of digital material as bootleg items, illegal copies, and, as Holly Isard put it, a version of Hito Steyerl’s famous idea of the ‘poor image’. This digital flow was one way of imagining ‘animating archives’, and which creating forms of unregulated knowledge. The second way of thinking about these digital reproductions was as our practice as researchers: taking multiple photographs and scans, making audio recordings as well as written notes, a mass of data that might get lost on our hard drives as the rush to gather materials in the archive is seldom matched by a cataloguing of digital material in our own personal research files. Althea said that this mass of digital material might be thought of as the ‘sub-conscious’ of our research, a site which is not designed to be rationally catalogued but performs some more opaque function as we orient our projects.

The sense of time-poverty that many of us face when thinking about the nearly always unequal relation between research time and amount of archival material to review is perhaps going to exacerbated when we can return to the archives after lockdown. But in the meantime, here are some reflections and digital objects from the workshop discussion:

Holly Isard

My digital object is a screenshot: a low-resolution version of Elizabeth Price’s 2013 video-work A RESTORATION uploaded onto YouTube by ‘disinformator’ and titled Elizabeth Price (1). I had been to visit the ‘real’ version of Price’s work in the Western Art Print Room at the Ashmolean Museum in the summer of 2018. Here, A RESTORATION is held on a memory stick kept in a small plastic box and stored in a ‘secret location’ in the archive. I am only the second person to have visited it (in high resolution, equipped with noise-cancelling headphones) since the print room acquired it in 2016.

In contrast, ‘disinformator’ has racked up 1,981 views. Elizabeth Price (1) conforms to what Hito Steyerl terms a poor image: ‘clandestine cell-phone videos smuggled out of museums and broadcast on YouTube.’ This is the digital version an archive might be inclined to ignore: a copy of a copy, bad resolution, illegally recorded, itinerant and unruly. But, according to Steyerl, these images ‘transform quality into accessibility’ and ‘exhibition value into cult value’, forming an alternative economy of images (Stereyl, 2012). In this way, ‘disinformator’s Elizabeth Price (1) raises the question of ‘value’ for the archivist. This digital objects’ status as illicit grants it exemption from the ‘class society of images’, which in turn allows it a certain kind of radical potential. Value then means something different in relation to the digital version, not aura of the ‘original’, high resolution and exchange value, but perhaps ‘velocity, intensity, spread’ and dematerialisation – as Catherine writes above, creating forms of unregulated knowledge that animate the archive in new, unruly ways.

Beth Bramich

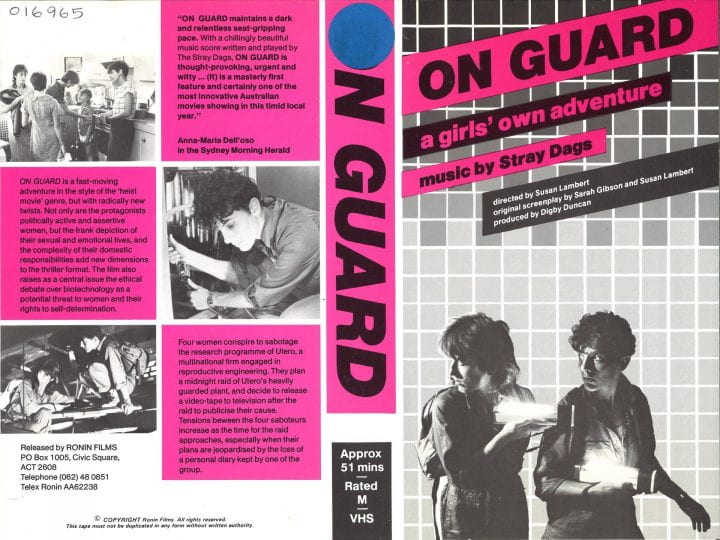

The digital object I shared was a scan of a VHS cover (or ‘VHS slick’) for the film On Guard, a feminist heist thriller directed by Susan Lambert and released in 1983. The scan was officially produced and circulated online by the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, which I had planned to return to earlier this year to continue research into film and video produced by members of the Sydney Women’s Film Group between 1973 and 1985. My intention had been to divide my time in the ACMI’s collections of the National Film and Sound Archive between watching films and videos I had identified since my last visit and exploring connected archives, including printed matter. Digitisation policies vary between archives, but it is not uncommon for film and video to be accessed through in-house transfers on to blank DVDs and VHS and therefore removed from their original format and packaging and accompanied by brief and often anonymous synopsis entries — at ACMI these were kindly printed out for me by the collection archivists as a long stream over A4 sheets. I am used to moving image archives separating out ephemeral print, which is not always accessed or even held in the same place if it has been collected. Looking at posters and packaging for distribution, although they may be considered secondary to the film, can be extremely illuminating of the public context of these works. It was through rereading a page of annotated synopses, notes and quick sketches, and struggling without this further context, that I began a range of Internet searches for On Guard, attempting to jog the connecting memories of my research ‘sub-conscious’ and answer questions that had arisen since my visit about exhibition and reception.

Through the Animating Archives workshop, I started to think about the ways in which questions form in this time in between — the possibility for connection and creativity that comes from moving through different types of content and their physical locations and digital circulations, like how film stills can reanimate memories of film sequences, or in the absence of the physical archives how several versions of ‘film name + film director + keyword’ searches can make new associations between official and unofficial archives. In this case, I began to sketch out a legacy for On Guard through its digital footprint: a screening at the 2017 edition of the Melbourne International Film Festival, inclusion in a 1986 Channel 4 series ‘In the Pink’ discussed in a personal blog on gay culture in the 1980s, a diversion into the film’s soundtrack with music by Stray Dags reissued this year by Chapter Records, a 2014 Senses of Cinema journal article. This last article’s image credit led me back to ACMI’s collection and the digitised VHS cover, but through this additional exploration I have further developed my shadow archive of the cultural and political context of this film after its release.

Susan Lambert, On Guard, 1983

National Film & Sound Archive, Australian Centre for the Moving Image

https://acmi.net.au/works/78364–on-guard/

Valeria Medici

This was the first time I’ve discussed archiving with people external to my cohort. Understanding and witnessing the role of archived images as they were prior to digital images has given me access to ways to implement physical methodologies into my own artistic practice. The carousel is an object I’m fascinated by, its mechanic and sounds are alien to me, although the images of the individual archived slides somehow retain their physicality and mechanic in a sonic way. After the workshop, I came to realise the importance of sound and of recorded discussions especially after watching the video Althea showed us. That moment is forever incorporated with the objects and images and to me this combination of images and sounds transport meanings and truths in a way nothing else does.

Web: valeriamedici.com

Published by