Our summer symposium bought together artists, curators, researchers and archivists to explore questions of collecting, access, accountability and platforming in archival collections. The first panel outlines the strategies of archiving within, alongside and in spite of institutions, while the second explores radical interventions and gestures that seek to form relationships, futures, knowledges and practices with the archive.

With many thanks to the panellists and contributors!

Round-table one: The Politics of Preserving (start-1:27:20)

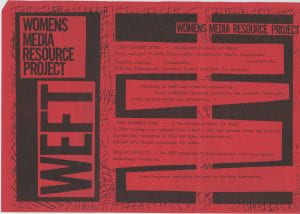

This round table thinks about the collecting strategies of archives and grassroots collections within institutions. The panellists are Shaheen Merali from the Panchayat Special Collection at the Tate Library, Stefan Dickers from the Bishopsgate Institute and Holly Argent from the Women Artists of the North East Library. Convened by Patrizia di Bello and Lily Evans-Hill from the Feminist Library.

Round-table two: The Politics of Opening up Access (1:27:20-end)

This roundtable thinks about digital, collaborative and interventional strategies of groups using archives, with contributions from Gina Nembhard and Lauren Craig of X Marks the Spot, Barby Asante, and Rosemary Grennan from Mayday Rooms. Convened by Althea Greenan from the Women’s Art Library and Catherine Grant.

Speaker bios

Panel 1:

Shaheen Merali is a curator and writer, based in London, who explores the intersection of art, cultural identity, and global histories. He has held positions at Central Saint Martins School of Art (2003-1995); a visiting lecturer and researcher at University of Westminster (2003-1997) and the Head of Department of Exhibition, Film and New Media at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2008-2003), one of the first Asian/POC to hold such a position in Germany’s history; a milestone appointment where he curated several exhibitions accompanied by publications, including The Black Atlantic – Modernity and Double Consciousness; Dreams and Trauma- Moving images and the Promised Lands (Palestine and Israel); New York States of Mind (toured to Queens Museum, NY) as well as leading the curation and global research for five years of programming. At the HKW he co-curated with Professor Wu Hung, Re-Imagining Asia, One Thousand years of Separation (toured later to the New Art Gallery, Walsall) and the 6th Gwangju Biennale, Korea (2006). Between 2009-8 he was the artistic director of Bodhi Art (Berlin, Mumbai, New York, and Singapore).

He has contributed to numerous exhibition catalogues, including Michael Wutz (Galerie Klaus Gerrit Friese), Probir Gupta (Anant Art) and Rita Keegan (SLG) as well as editing a series of monographs including Tavares Strachan, I AM for Desert X (Isolated Labs), and JJ XI (Carrots Publishing). He has lectured at many institutions and was the co-convenor of This is Tomorrow: de-canonisation and decolonisation at the Courtauld Institute, London in November 2019 and leading the structured conversations for the AHRC’s Towards a National Collection programme Provisional Semantics Case Study, on Panchayat Collection held in the Special Collections of Tate Library. He is currently on the advisory board of the Live Art Development Agency (London) and a PhD candidate at Coventry University.

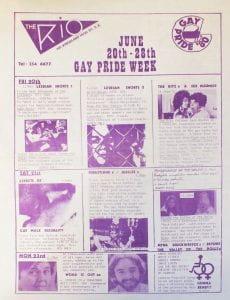

Stefan Dickers is the Special Collections and Archives Manager at Bishopsgate Institute and has been responsible for the development of the Institute’s collections on the history of London, protest and activism, and LGBTQIA+ Britain.

Holly Argent is an artist and researcher based in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. She founded and leads the Women Artists of the North East Library (2017-). Through both her artistic practice and work as project lead for the library, she is interested in creating contexts and perspectives for exploring artistic legacies and conflicting histories, always looking to emphasise a subjective position to reflect or expand upon complex autobiographical narratives. Later this year Holly will be the 2021 BALTIC Bothy artist in residence on the Isle of Eigg, Scotland.

Panel 2:

Rosemary Grennan is part of the collective that runs MayDay Rooms, an archive and educational space in London which seeks to connect histories and documents of radicalism and resistance to contemporary struggle. She is interest in building open access digital archives and experimenting with technologies and infrastructures associated with this. For this session Rosemary will talk about the project she has recently been working on with 0x2620 Berlin: Leftovers, a collaborative online archive of political ephemera. She is also completing a PhD in Material and Visual Culture from University College London.

Lauren Craig is a London-born artist of Jamaican heritage. Her practice encompasses her lived experience and auto-ethnographic approach as a cultural researcher, full-spectrum doula and celebrant, living and working in London and Central Italy. Through photography, video, text, installation, performance and writing, she explores equally broad themes of ecofeminism, spirituality, health, memory and the propositional. Craig’s current research/practice incorporates restorative writing circles with photographic, moving image and therapeutic and reparative archival methods to create and document the creative genealogies of contemporary celebration, rituals and commemoration within the practices of womxn of colour artists and their allies. Lauren aims to further her practice-based research on MRes Arts and Humanities, Royal College of Art (2020/2021) with the aim to continue at doctoral level in the UK. Lauren is a member of X Marks the Spot (XMTS) an ongoing artist archival research collective founded 2011 at Studio Voltaire London in response the work of Jo Spence and Judith Hopf. Since 2013 XMTS have worked the Women of Colour Index (WOCI) producing, Human Endeavour: A creative finding aid for the Women of Colour Archive, (2015) published with Women’s Art Library, Special Collections, Goldsmiths where the WOCI archive is held. The ‘Women of Colour Slide Show’ explores reparative methods through digitally restored 35mm slides in a meditative fusion of role call, tribute and invitation. This has been shown at Tate Britain (2018) and the Centre for Contemporary Art, Goldsmiths (2019).

Gina Nembhard has spent a number of years involved in art and design projects both practicing and assisting artists. Initially Gina developed her mixed media work and fine art textiles embroidery and later whilst studying, worked in a London based all-female architecture practice (A.T.A.P). Later her studies in sustainable product design led her to develop a business/practice combining both art/craft workshops focusing on a broad range of making including upholstery, textiles, stitch and dyeing. Within her work she tries to maintain a consistently sustainable perspective. As a member of X Marks the Spot, a collective of women practitioners and artists initially formed whilst in residency at Studio Voltaire, Gina has been involved in a number of talks, workshops and residencies on the subject of artists and archives.

Barby Asante is an artist, curator and researcher. Her artistic practice is concerned with the ever present histories and legacies of slavery and colonialism, exploring archival injustice and the importance of remebering through re-collecting, collating, excavating, through the action of mapping stories and narratives, collective writing, reenactment and creating spaces for transformation, ritual and healing. With a deep interest in black feminist and decolonial methodologies, Barby also embeds within her work notions of collective study, countless ways of knowing and dialogical practices that embrace being together and breathing together. Barby has taught in fine art programs in London, Berlin, Gothenburg and Rotterdam and was co-founder of agency for agency, a collaborative agency concerned with ethics, intersectionality and education in the contemporary arts who were mentors to the London-based sorryyoufeeluncomfortable collective. Her recent exhibitions and projects include: As Always a Painful Declaration of Independence: For Ama. For Aba. For Charlotte and Adjoa Diaspora Pavillion, Venice, 2017, BALTIC, Gateshead 2019, Bergen Kunsthall 2020: Black Togetherness as Lingua Franca with Amal Alhaag, Framer Framed, Amsterdam, 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning, 2018; Baldwin’s Nigger R E L O A D E D, InIVA, London, 2014, Somerset House, London 2019; Cracks in the Curriculum: Countless Ways of Knowing, Serpentine Gallery, London 2018: SERP Revisited with Barbara Steveni, Flat Time House/ Peckham Platform, 2018. She is also on the boards of the Women’s Art Library and 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning. Barby is also a PhD Candidate within CREAM (Centre for Research in Education, Arts and Media) at the University of Westminster.