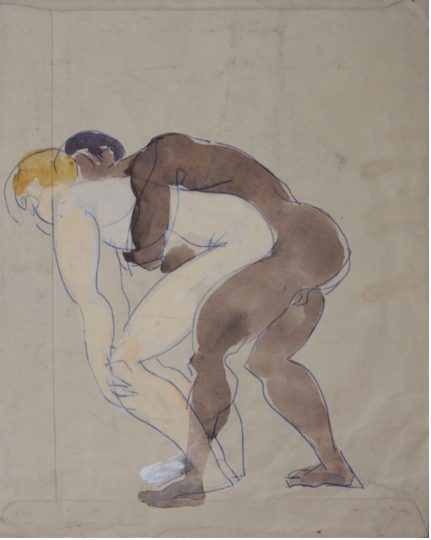

Photo courtesy of the Charleston Trust © the Estate of Duncan Grant

In the 1950s and 60s, the white British artist Duncan Grant created an archive of over four hundred and twenty erotic drawings, the majority of which depict queer sex scenes, many of them interracial. Born in Rothiemurchus, Scotland in 1885, Grant became one of the central figures of the Bloomsbury Group and rose to prominence in the early twentieth century as a painter, decorator, and textile designer. In 1916, alongside fellow artist Vanessa Bell and his then-lover David Garnett, he moved to Charleston near Firle, Sussex. The discovery of the extraordinary collection of erotic drawings in 2020 after their donation to Charleston Trust, demands that renewed critical attention be paid to the role of Black people in the histories of Modernism, the Bloomsbury Group and queerness in twentieth-century Britain.

A crucial challenge I have faced in my PhD research on Grant’s erotic drawings has been how white supremacy structures the archive. Although prominent white members of the Bloomsbury Group left a plethora of autobiographical material, anti-racist scholars are challenged by a lack of written evidence available regarding how individual Black people impacted their life and work. As a white queer and trans researcher without first-hand experience of racism, centring the work of Black scholars and writers methodologically has been vital in my critical engagement with Grant’s work. I have been influenced by historian Gemma Romain and writer Shola von Reinhold, who employ two distinct approaches that seek to expose and challenge how white supremacy is embedded in archival structures. In her biography of Patrick Nelson, a Jamaican valet, artist model and lover of Grant’s, Romain explores how archives are implicated in racist knowledge production proposing scholars should ‘read against the grain’ (following the work of theorist Ann Laura Stoler) to counter these challenges. Within Grant’s erotic drawings, distinguishable facial features are frequently elided, their focus resting instead on the sexual scenes depicted. As such, it is difficult to determine whether Patrick Nelson himself modelled for these specific works, which differ stylistically from paintings such as Grant’s portrait of Nelson made in the last years of his life in 1960-1963. Nevertheless, the artist’s recurring fascination with interracial sex between white and Black men raises questions about Grant’s relationships with men like Nelson outside of his work, rendering Romain’s work crucial in contextualising the collection.

In contrast, Von Reinhold’s novel LOTE challenges the binary division between fiction and historical research, offering the character of Hermia Druitt as an amalgamation of the archival traces which hint towards Black involvement in British Modernism.

Both LOTE and Romain’s biography of Patrick Nelson articulate the challenges faced by scholars of Black queer Modernism—how racism structures which material is preserved, catalogued, and deemed valuable. In LOTE, we see how Black researchers specifically are marginalised in the archive through economic and academic marginalisation. Whilst Gemma Romain reads mainstream collections such as the Ministry of Defence and Tate Archives subversively, working within institutions structured by white supremacy in ways opposite to their design, Shola von Reinhold uses fiction to consider the historical connections that may be crafted outside of archival structures.

Against the Grain

In Race, Sexuality and Identity in Britain and Jamaica (2017), Gemma Romain tells Patrick Nelson’s life story which spans several sites of historical interest. After his youth and adolescence in Jamaica, working as a valet in a Kingston hotel in the 1920s and 30s, Patrick emigrated to Britain, working first in domestic service in rural Wales and then as an artist model in London. During World War II, Nelson served in the British army and was captured as a prisoner of war by German forces. Upon his release, he ventured back to Jamaica until his eventual return to London in 1960, where he died three years later. Romain’s chief archival sources relating to Patrick Nelson are drawn from the Ministry of Defence Personnel archives and the letters he wrote to Grant, held at the Tate Archives. After becoming lovers in the 1920s, these written records of Nelson’s relationship with Grant chronicle a decades-long friendship that lasted until Nelson’s death in 1963. Yet Romain draws our attention to archives as sites of knowledge production which are inherently political. Rather than seeing the archive as a neutral site of source collection, researchers must focus on why collections were created. Patrick Nelson’s letters to Duncan Grant survive because they have been deemed relevant to the biography of a white British artist, making it more difficult to trace Nelson’s story on his own terms. Romain reminds us that the rationale behind archival creation specifically works to obscure the histories of those marginalised by structures of racism, sexism and classism.

In order to challenge the structural barriers faced when uncovering Black queer histories like Nelson’s, Romain reads the archive against the grain, following biographical information about her subject in alternative ways. Through Patrick Nelson, she connects interwar Black British life with the Bloomsbury Group, research which had until then largely focused on the affluent white artists and writers affiliated with the set. By seeking to highlight Nelson’s story in an archive which catalogued his life only in reference to his white lover, Romain provides an important corrective to this implicit bias towards whiteness in the historiography. Through Nelson, we see the presence and impact of Black queer men on Grant’s inner circle, laying important groundwork for future efforts by historians to make this impact visible.

The importance of Romain’s methodology is underscored by racist narratives which refute the existence of Black people in early twentieth-century Britain. She explicitly challenges the claims of Juliet Gardiner, a historical consultant for the 2007 film Atonement who, in a 2013 BBC Radio 4 programme, ‘Presenting the Past – How the Media Changes History’, critiqued the inclusion of a wounded Black soldier at Dunkirk in the film because it would have been ‘almost impossible’ for a Black man to fight for the British army in France during World War II. Patrick Nelson’s life story challenges this historical erasure, and Romain’s inclusion of this statement emphasises the racist dynamics operating in academia which work to erase Black history within archival practices and beyond.

Out of the Archive, Into the Streets?

In LOTE, Shola von Reinhold uses fiction to explore how racist attitudes within research communities and archives function to erase Black queer histories. In the first part of the novel, the heroine Mathilda works at the National Portrait Gallery Archives. Alongside an older Black woman, Agnes, she is asked to catalogue a collection of old photographs, in which she discovers of picture of Hermia Druitt, a glamorous Black artist and socialite, at a party held by Lady Ottoline Morrell, attended by Bloomsbury Group members like Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, alongside ‘Bright Young People’ like Stephen Tennant. The donation they are working with has been in the archive for a long time, unlooked at, hinting at many more traces of Black queer Modernism hidden in collections across the country, which are not deemed worthy of the resources to catalogue them.

Similarly, the collection of Duncan Grant’s erotic drawings, created in the late 1940s and ‘50s, was hidden from the public for sixty years. Conceived during a time when homosexual activity between men was still illegal, Grant first passed them on to affluent friend and painter Edward le Bas in 1959. The collection was then passed from friend to friend, lover to lover, until they came into the possession of South African theatre designer Norman Coates, who kept the drawings under his bed for eleven years before donating them to Charleston. It is difficult to assess how far the interracial nature of many drawings in the collection contributed to them remaining in private collections for such a long time. Nevertheless, it is significant to note that access to these representations of interracial desire between men was chiefly afforded to affluent white gay men in the art world. As a result, the question of how to make the collection more accessible to researchers remains crucial. In time, I hope to create a digital online archive of the drawings to tackle the physical and institutional barriers that prevent audiences from accessing these images.

From the outset of LOTE, the ability of Mathilda and Agnes to retrace Black queer history within British Modernism is contingent on white gatekeepers, namely an affluent young white woman called Elizabeth/Joan and James, her boss who initially refuses Mathilda entry into the archive by pretending it is a private member’s club. This power imbalance is emphasised further by the fact that whilst Elizabeth/Joan and James are employed by the archive, Mathilda and Agnes are unpaid volunteers. After the two have catalogued some of the donations, including the Hermia Druitt photograph, James challenges Mathilda on the date assigned to the picture:

“Some of these dates are way out,” he said without looking up.

“We’ve gone through them all properly, at least twice. ”

“This one for example,” he said, and it was the picture of Hermia, the one I’d just put back. “Yes, look: one of you has put ‘circa 1920’ on the sheet but it’s obviously no more than 30 years old. Black and white, maybe even an old camera, but contemporary.”

James’ dismissal of Mathilda and Agnes’ expertise is uncomfortably reminiscent of Juliet Gardiner’s assertion that it would have been ‘almost impossible’ for a Black soldier to be at Dunkirk. Mathilda’s experience in the archive translates to the reader how the structural racism of the archive works in practice; through the disincentivisation of scholarship due to poor working conditions, power imbalances between those who oversee collections and those who access them, and the foreclosure of research not deemed worthy under white supremacy.

Romain uses existing archival collections in new and unexpected ways, and Mathilda breaks Hermia out of the archive. She steals the photograph, as an act of liberation which allows it to become more alive: “I felt it might dissolve in my possession, outside of the archive, but instead it became more substantial, if anything materialising not dissolving—sucking in atoms, becoming more of an object, more vivid.”

Escaping the archive becomes a way for Mathilda to harness a historical connection with a figure in Black queer Modernism which is intimate and embodied. Hermia takes on the role of a divine figure for Mathilda, connecting her subjectivity with a heritage of Black queer Modernism. Yet it is only upon leaving the archive that this quest can begin in earnest.

Archival Bias of Black Queer Figures in British Modernism

Both Shola von Reinhold and Gemma Romain’s texts make visible the structural inequalities that underpin archival research, specifically as they pertain to the influence of Black queer figures in British Modernism. As part of my PhD research, I will apply Romain’s methodology of reading against the grain to the Duncan Grant archive. Using The Charleston Papers at the University of Sussex’s The Keep, I will read an archive intended to preserve the legacy of prominent white members of the Bloomsbury Group to trace references to the Black men who influenced Grant. I hope to trace further links between Grant’s circle and queer Black men such as Richie Riley and Berto Pasuka, who founded the all-black ballet company Les Ballets Nègres in 1946. Riley was a friend of Nelson’s who informed Grant of his death in 1963. In contextualising relationships like that between Grant and Nelson within a wider queer Black artistic community in twentieth-century London, I will seek to challenge the archival biases which have marginalised the role of Black queer figures in British Modernism.

I hope to use my privilege as a white researcher working within institutions to broaden access to the collection of Grant’s erotic drawings. Drawing on LOTE’s exploration of the racialised dynamics which prevent access to archival collections, making this vast collection of works available to the public will encourage a broader set of audiences to engage with Grant’s work. Mathilda’s quest to uncover Hermia’s story situates the researcher within the dynamics of power that have marginalised Black queer history. Rather than employing von Reinhold’s fictional methodology, I will dedicate a chapter of my PhD dissertation to connecting Grant’s erotic drawings to current political and theoretical concerns. Aware of my positionality as a white researcher, I hope that the digital archive I am collating will generate responses from Black queer scholars and members of the public, so that I may use this space to generate a dialogue surrounding representations of interracial sexuality in the works.

Samson Dittrich is an interdisciplinary researcher in trans and queer masculinity studies. He is a first-year doctoral candidate at the University of Sussex, working in conjunction with the Charleston Trust to explore a collection of over 422 erotic drawings by Bloomsbury Group artist Duncan Grant.

Published by