Anyone who was born out of a mother ought to know that originality is at best overrated and in all probability impossible. Yet in the art market and the academy, the uniqueness of an object and its equally unique relationship to its producer defines value. The prescribed value of the object then allows it to be traded in the commodities market, as well as the marketplace of ideas, where timeliness and originality of research attracts both cultural and literal capital, in the form of salaries, fees and grants. Be it AHRC, CHASE or ultimately the Research Excellence Framework, individualised work on discreet objects with expedient political or social purposes is rewarded.[1] While the messy, bruising, frictions of collaboration, both formal and informal, are marked as surplus. So, what is the value and place of these practices and what forms of archiving and methods of research can re-produce their resistant obstinance to marketisation? And furthermore, how does this relate to both practical and metaphorical divisions of gender in labour, invoked here through the determining condition of maternity.

The above photo photograph, taken in 1982, belongs to a collection of digital files, given to Dr Patrizia Di Bello, as part of the handover of the Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive to Birkbeck University by the photographer, historian and activistTerry Dennett. As a digital file the photo doesn’t reside within the main physical collection. The fate of the digital files is yet to be determined, so currently, it remains absent from the public research record. In this image, t Terry Dennett (1938- 2018) holds and kisses the hand of his partner, photographer and self-identified “cultural sniper”[2] Jo Spence (1934- 1992.) Neither look directly at the camera, or each other, their heads touch, they form a unified triangle in the middle of the frame. Spence looks tired, she is undergoing treatment for breast cancer, her eyes are focused elsewhere, there may be someone or something else in the room. There is no attached caption for this image, beyond the date included the file name, no note as to whether a third party took the photo, or whether they used a timer. It’s hard to name a definitive producer, but we do know that it was Dennett that kept it.

In the background of the photo is a disordered domestic space, likely to be the flat at 152 Upper Street in Islington, London, in which Spence and Dennett lived and worked during a period of their partnership. It is a photograph of two people who were collaborators and lovers. A partnership that dissolved, Spence married David Roberts towards the end of her life, yet despite this change in circumstance it is the partnership that laid the ground for the legacy of Spence’s work that exists today. A legacy is, in no small part, upheld by the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, curated, and maintained by Dennett at 152 for the twenty-six years between their deaths. Dennett’s cohabitation, first with Spence and then with the remainder of her work, was both the engine and the condition for the history we have of Jo Spence and her collaborators.

Maternity, used here metaphorically and as an essentialist polemic, is predicated on a durational interaction leading to cross contamination between entities. The unoriginal creativity of maternity offers a descriptive parallel for collaborative practices in which one or more individuals nurture or shield the work of one or more others. In the maternal relationship, work is latently co-produced after the “event” of its creation, altered, and embellished by the continuing co-existence of the object and its protectors. Refering again to the generic experience of having a mother, we can all recognise the entropic indivisibility of the mother and child relationship. A definition of archival practice as reproductive, rather than static, is transformative in the historicization of grassroots political art practices, where the purpose of the work was always to form sociality around the objects. This is particularly true of the photography of Jo Spence and Terry Dennett and the character of the Jo Spence Memorial Archive at Birkbeck University.

Archives are dialectical in character; they form an image of almost infinite variety while preserving a collection of specified and finite material. In doing so the archive presents an implausible dichotomy between inside and outside. The division between what can be inside and what should be kept out is a marker of value, the selected objects were worth keeping due to their academic or market potential. Today the Jo Spence Memorial Archive is split between Birkbeck University in London and the Ryerson Image Centre in Toronto,[3] who own the image reproduction rights, while the gallerist Richard Saltoun in London represents the Estate of Jo Spence. The Ryerson houses the bulk of the collection left by Dennett and is in the process of being categorized via the institution’s archival logic of filing and annotation. The Birkbeck collection remains less systemised and more umbilically related to the organisational principles used by Dennett in his home, which were marked by his co-existence with the material, stacked according to his need and ease.

The photo of Spence and Dennett we see here has slipped between archival spaces, associated with but not contained by the Birkbeck archive, and it’s slipping it has pulled at the gauze between valued and de-valued articles. As an image it is generic, a digital transfer of a personal snapshot, one jpg amongst dozens in a file. There’s nothing remarkable about the composition and content, a white middle-aged couple showing some signs of wear and tear. Behind the couple there is a haphazardly pinned poster of some workers, at rest or on strike, the image includes block of text and is likely to be a poster for one of the Half Moon Photography Workshop exhibitions that Dennett and Spence collaborated on in the 1970s. Some of these posters are kept at Birkbeck in archival boxes. Taken on analogue technology, the film has been doubly exposed, and the figure of Dennett is partially obscured by a milky band of light. The double exposure has unintentionally created an in-camera montage of Spence Dennett’s domestic life, inlayed from another photo of the film roll is a numbered ticket, perhaps from a raffle? A dry cleaners’ stub. A ticket from a hospital waiting room? The number should be used to recall an object but that now is severed from its referent via time and context. The accidental inclusion of the ticket mimetically evokes the relationship between the document and experience which it represents; an index without recourse.

We keep photos of people we love because we value the person, and their objectified image becomes a totem via which to honour them. There is no explanation needed for the value placed in the photograph by Dennett, but its lack of value in both the art and academic marketplaces as demonstrated by its lack of officiation, marks it with ambiguity. An ambiguity exacerbated by the photographs’ similarity and proximity to other works made by Dennett and Spence, which have been definitively categorised as photographic artworks or as documents of note.

The domesticity of the photograph is not a uniquely distinguishing factor, Spence, and Dennett’s most well recognised project Remodelling Photo History (1981-2)- a series of panels of photographs mostly using Spence’s body as symbolic depictions of forms of industrial, cultural and domestic labour- was in part shot in their home. Neither is the inclusion of the image makers as photographic subjects; Spence appears in much of her photography, and Dennett with her in Remodelling Photo History. Even the montage, as accidental as it may be, helps to tie the snapshot to the couple’s wider body of work through formal similarity. Yet we know from its archival location, which at present could be described as associative rather than categorised, that this image has been deemed outside of the boundaries drawn by market value.

In 1983, the photographer and theorist Allan Sekula wrote; “Anyone who has sorted or simply shifted through a box of family snapshots understands the dilemma (and perhaps folly) inherent in these procedures. One is torn between narrativization and categorization, between chronology and inventory.”[4] The dilemma and the folly which Sekula describes, emerges from the aggregate materiality that documents our public and private lives: of which photography is one element, as are birth certificates, love letters, utility bills and library cards. These materials act as positive registration points for the excessive and incoherent experience of having a human life, they mark out moments of connection and obligation, accounting for us. In an essay on the British worker’s movement of the 1930s, and the movement’s use of the photo album as an educational tool, Dennett articulated a similar sentiment to that of Sekulla, Dennett wrote: “Life provides the ‘plot’, the ‘storyline,’ the events are not necessarily photographed in real time but can be re-enacted or reconstructed to give a distillation of ‘what happened’.”[5]

Both Sekula and Dennett recognise the tug between the ordering of documents and the emotional, domestic, and even political chaos that unfolds as narrative on the interpersonal level; and both Sekula and Dennett identify this friction as a question of ascribed value. For them, the photographic document is a pivot on which the relationship between the biography, the archive and individuated identity, tip. Tipping, tugging, slipping, the ambiguity of the value of the photograph of Dennett and Spence is matched by the ambivalence of photographic technology as an institution. The confusion of scales of value present in the photo of Dennett and Spence is not just a question for the posthumous market significance of Spence’s legacy; but for the role of photography, and in this case photographic portraiture, for de-marking the boundaries between public and private and the value we subscribe to both realms. It is this demarcation and the possibility of trespassing against is, which provide a root into the alternative value system held by the photo of Dennett and Spence.

The domestic sphere was historically categorized as feminine, and the derision of women’s work in the home is something Spence focused on in her photography. In Remodelling Photo History Spence and Dennett explicitly addressed the gendered divisions of labour, through their own experiences as well as through wider cultural tropes. They wrote in the Screen journal publication of Remodelling Photo History:

“We also hoped that the tension between us as two individuals, with overlapping philosophies of historical materialism— grounded here in Terry’s study of specific apparatuses and the economic point of production as central to any understanding of history, and Jo’s interest in women in a class society relation to reproduction and domestic labour— could productively raise a series of presently unvoiced questions. The work also comes from our (separate) experiences- as a scientific photographer (Terry), and as a commercial portrait photographer, now analysing a visual socio-economic history of the family (Jo).”[6]

In Spence and Dennett’s description they weave together their personal, professional, and photographic lives. Making each facet dependent on and answerable to the other, continuously acknowledging the different stakes and experiences they have had as respectively, white working-class British, men and women. In Spence and Dennett’s collaborative practice women are not presented as their own potentially revolutionary class, but as labouring subjects intertwined in the sticky attachments of family, political and social life. The feminism of these depictions is not a politics of separatism but a materialist diagnosis of the conditions under which feminine and masculine identities are produced through work and technologies of representation.[7]

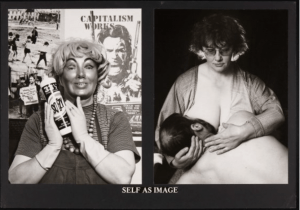

In the above image we can see one of the panels from Remodelling Photo History ‘Self As Image.’ On the left Spence poses in a mask, wig, holding a bottle of cleaning product in front of political posters pinned to the wall, this scenic montage is perhaps a refrence Martha Rosler’s photomontage series Brining The War Home 1(967-72.)[8] On the right, Spence breastfeeds Dennett. Most of the panels from Remodelling Photo History use this form of dialogical, side by side comparison of images, to juxtapose the gestures and details composed within each image. This strategy of montage was drawn from Dennett’s research into the photography of the British workers’ movement of the early 20thcentury is referred to as The Deadly Parallel. In the 1920s and ‘30s The Deadly Parallel was used in radical printed material to demonstrate discrepancies between meaning and evidence and relies on open form of comparison to stimulate critical thought on the part of the viewer/ reader. If this, why that?

The panel I have selected to share here is an amputation from the from the sequential work, as the image of breastfeeding is convenient to the thematic of my argument, which deals with transgression in the value of maternity and feminized labour. The photograph clearly is a reference to religious images of the Madonna and child, Spence’s untamed hair is back lit to create a halo, she cradles Dennett whose male pattern balding and general physique exaggerates the comic effect of the replacement of the infant Christ with a middle-aged man. However, reading this photo through the technique of The Deadly Parallel, it can also be seen as a comment on the re-productive nature of women’s labour. The images draw on the arbitrary policing and division imposed on women’s bodies, particularly around breastfeeding where the woman’s pleasure is taboo if coded in any way erotic, while the same act is a normative part of adult sexuality. We implicitly understand that it is the distinction of the relationship between mother and child and a woman and a sexual partner that distributes and controls the potential eroticism of such an act. However, rendered as an image we are confronted with the notion of the taboo around breastfeeding and eroticism, and asked to consider the possibility of transgression. Compared with the image of Spence as the masked cleaner, the mask itself recalls the face covering used by bank robbers and terrorists, in which Spence posed against the political posters, the breastfeeding image taps to the cultural suppression of women’s libidinal urges whether they are violent or sexual.

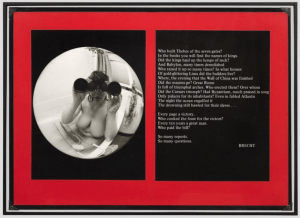

The second segment of Remodelling Photo History reproduced here is titled ‘The History Lesson’, after the Bertolt Brecht poem included in the right-hand panel. The left-hand panel shows Spence in the bath (her and Terry’s bathtub) looking into a camera’s fisheye lens with binoculars. The image of Spence in the bath carries some of the humour associated with Spence’s work. Contrasted to bathetic consequence with the Brecht poem, placed on the red-for-communism background, the parallel images are an explicit appeal to the viewer to concern themselves with the political history of photography and photo-making. Spence’s gaze out from the tub is to that viewer, us, and in meeting her gaze our “readership” of text and image is demanded and activated. Of course in the production of the image, Spence’s gaze was fixed on Dennett as he photographed her.

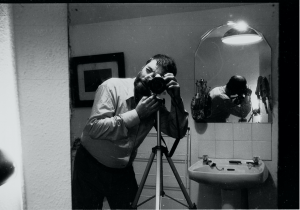

In the consignment of digital files received by Di Bello, the same collection which included the portrait of Dennett and Spence in their living room, was a sub-file of images from the Remodelling Photo History shoot, images that had not been included in the final iteration of the project. I am reproducing one of these photographs here, a self-portrait by Dennett, in the bathroom mirror.

Again, if we borrow from The Deadly Parallel method of reading and compare this image of Dennett to the panel of Spence and Brecht, there is somatic ease to the motion and composition of this photograph. Unlike the arch Brechtian humour-via-estrangement of ‘The History Lesson’ panel, it is easy to place oneself in this photographic situation. To imagine Dennett turning from Spence, away from her binoculared gaze and their prosthetic-on-prosthetic contemplation towards the mirror to face himself and snapping the photo.[9]

As easy as it is to understand the urge to self-document, it is as easy to understand why this photograph was never considered for the highly scripted text and montage work of Remodelling Photo History. It’s a portrait on the cuff, an element in the continuous seriality of film photography, snap after snap. It is an image of a man looking at himself, which was edited out a work about photography’s role in the gendered divisions of labour in a post-industrial society. The images’ exclusion is easy to understand, but as in all editorial processes, that which is removed is negatively rendered. This photograph is a redacted or alternative parallel to the image of Spence in the bath.

In his television programme and subsequent book Ways of Seeing, John Berger described the role of men and women in the world of images as such: “Men act, and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed is female. Thus, she turns herself into an object of vision: a sight.”[10]

The construction of the feminine, in the view finder of the masculine, and the transmutations that enforced exhibitionism forces in the feminine subject is evidently at play in Remodelling Photo History. The construction of photo series is a form of editorial ambivalence, ambivalence meant in the Freudian definition of two oppositional and equally strong forces which co-exist within the subject. Side-by-side images which correspond but contradict one another, and text which both captions and disavowals the meaning of the photograph. In this work the production of meaning is dialogical between the man and woman involved in the image production.

However, it is not just the binary and the distinction which is salient in Berger, Dennett and Spence, as Berger wrote: “The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed is female.” The question here is not the inverse of Berger’s proclamation: Do men recognise the feminine in themselves when they look in the mirror? Or Did Dennett see tropes of femininity in the act of representing himself? Or even an issue of Dennett reclaiming masculine tropes, by imaging himself as the man in charge of the equipment, phallic machinery at the ready to point and shoot. Rather what is at stake it is the splitting of the identity of the female coded subject through the act of looking and reproducing, and the acknowledgement that to produce the conservative, heterosexual, cis-gendered subject there must be the ambivalent force of opposition inside that same subject to discipline its performance and behaviour.

While Berger identifies this as a specifically feminised experience, one could ask what produces the specificity of a “woman’s life” and if in fact some of these ordering principles, domesticity without entitlement to property, labour without access to a fair and equal wage, the inability to represent oneself, were radically altered between 1971 when Berger presented Ways of Seeing, and 1982 when Spence and Dennett published Remodelling Photo History.

Britain, 1982, was a year dominated by the Falkland’s war, it was Margaret Thatcher’s third year as Prime Minister and the year that it was announced that 4000,000 council homes were sold through the Conservative government’s right to buy scheme. 1981-1982 are the years in which all the photos I have presented here were taken, inside 152 Upper Street. Outside of Spence and Dennett’s home the political, economic, and social landscape of Britain was changing. Over a decade of the women’s movement had given the country both the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp as well as Thatcher’s international war and her economic wars at home. The 1970s had changed the role of women in civic society, as economic subjects as much anything else. As women entered the labour market, and as they have continued to occupy it, the cultural boundaries between masculine and feminine roles have become unbuttoned at least on the level of the economic.

Today, under neoliberal wage relations we are all androgynous subjects, consumer-serfs with access to credit. This transformation in gender roles, in this economic register, occurred alongside and intertwined with Spence and Dennett’s period of collaboration. Projects such as Remodelling Photo History track the changing function of heterosexual dynamics between labouring people. Heterosexuality understood, not a as natural and transhistorical state, but as an institution which like all institutions exists house a multiplicity of class interests at a given moment in time. The changes in the labour market brough about by women’s liberation is something that twenty-first century feminism is having reckon with. If this is what happened to women, then what happened to men? And if that question cannot be answered here in its entirety here, then what happened to Terry Dennett?

Dennett did not own the flat on Upper Street, he was never a wealthy man. The bathroom depicted in his black and white self-portrait also functioned as the darkroom and photochemical processing lab for his and Spence’s work. It feels undignified to rake over the intricacies of the breakdown of a relationship, even when and where that information is available, but it is possible to state that Spence did not end her life in the flat which had held both the public and private parts of her and Dennett’s lives, often all at once in the same bathtub. Spence died of leukaemia in May 1992, having lived for the later part of the 1980s and early 1990s with her then husband David in a bigger and more comfortable home.

The Final Project (1991-1992) which documented the end of Spence’s life was a collaboration between Dennett and Spence, so if all we can know of a dead person’s biography is the public records, positive accounts, documents, and photographs, we know that Spence and Dennett remained intertwined in some way, as they are in the photo of them holding hands in the living room, which was also their studio space, at 152. After her death Dennett dedicated himself to Spence’s memory and their collaborative work, cared for the material and distributed to institutions and organisations that could keep the radical and pedagogical potential of their practice incubated when he was no longer able to.

To call Dennett’s maintenance of the Jo Spence archive maternal is not to claim that he was a mother.[11] Or that there is something intrinsically uterine about the interiority of archival space, or even that the level of recognition Spence has gained since her death is in anyway emasculating to Dennett’s own legacy. To define Dennett’s work as a form on inverse, masculine, maternity; as a practice of care that tracked the end of Spence’s adult life, towards her death when she was returned to the unproductive and infantilised state of the very sick and old, is to deliver the ambiguity of value we see in this photograph of Spence and Dennett into the historicization of their practice. The inversion of biological identity, at least on a notional level, is intended to recognise the ambivalence of the photographic image, and of photographic practice including its redistribution and archival mode. I contest that the meaning of the photograph reproduced at the start of this paper comes from where it isn’t. It’s not in the officiated record, it is not a work of art, it isn’t valued by the art market or art history. To understand its value and role we should meet its ambiguity with an argument for the ambivalence of technological reproduction, social reproduction, and value in a marketized world.

Saying something is alike but different pulls open a conceptual space of comparison, The Deadly Parallel. The application of feminine characteristics to Dennett’s labour is not a retroactive queering of cis gendered male and female relations but the acknowledgement that it is the hierarchies of value which defined and split these categories in their historical moment. The existence of the maternal state is an organic refusal of the dichotomy between interior and exterior, the original and the discarded. But childbirth is not a metaphor, photography is not a metaphor, neither is the archive. To think of Dennett’s practice as maternal, or the Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive as umbilically related to his and Spence’s partnership is not claim either as natural phenomena divorced from the conditioning effects of capital and labour; rather it estranges those categories from one another and in doing so redistribute the codes of value prescribed to them. Photography is analogous, maternity is a promise and a threat. Historical biography is a simile.

Alexandra Symons Sutcliffe

[1] And if not this, the method of “collaboration” prescribed by these funding and rewarding bodies borrows for the model of scientific investigation where hierarchical teams are developed and “lead researchers” are singled out as the specifically genius managers.

[2] This was Spence’s own definition of her critical photographic practice which aimed to dissect British classed and gendered social norms. The posthumously published collection of photographs and writing, Cultural Sniping: The Art of Transgression, Routledge: Milton-Park Oxfordshire, 1995 offers an overview of Spence’s biography, practice and how she came to this definition.

[3] The Birkbeck collection is known as the Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive and contains books on Jo Spence, books owned by Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, as well as materials relating to the Photography Workshop Camerawork magazine and Terry’s own practice. Th Ryerson Image Centre hold the Jo Spence Memorial Archive, which contains work from Spence’s entire career as well as her collaborations with Dennett, Rosy Martin, David Roberts, the Hackney Flashers and others. The Ryerson does not hold any tertiary materials.

[4] Sekula, Allan ‘Between Labour and Capital’ in Mining Photographs and Other Pictures: A Selection from the Negative Archives of Shedden Studio, Glace Bay, Cape Breton ed. Benjamin H.D Buchloh and Robert Wilkie, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and The University of Cape Breton Press: Halifax: 1983 p.197

[5] Terry Dennett ‘Popular Photography and Labour Albums in Family Snap: the meaning of domestic photography ed. Jo Spence and Patricia Holland, Virago Press, London: 1991 p.83

[6] Spence, Jo and Dennett, Terry ‘Remodelling Photo History: An Afterward on a Recent Exhibition’ in Screen, Volume 23, Issue 1, May/June 1982. Accessed https://academic.oup.com/screen/article-abstract/23/1/85/1594395?redirectedFrom=PDF p.85

[7] Jo Spence was involved in many forms of feminist organisation, including women’s only photography groups such as the Hackney Flashers. My claim is not that Spence personally disavowed that form of feminist work and practice but that this paper is focused on the heterosexual productivity of her and Dennett’s collaboration.

[8] By the early ‘80s Spence and Dennett were in contact with Rosler and her partner Alan Sekula, letters between them are held at the Ryserson Image Centre.

[9] This argument carries the weight of poetic license. The photograph of Spence in the bath used in Remodelling Photo History uses a fisheye lens, Dennett’s photo of himself does not, so it’s not quite that he was putting himself in the picture in response to documenting her.

[10] Berger Ways of Seeing broadcast on the BBC 8th of January 1972.

[11] Neither Dennett or Spence had any children.

Published by