Going to the Triangle (my happy place), an LGBTQ+ centre in Deptford.

One of the many happy memories of the borough.

(W19)

If for any reason you wish to withdraw your name or memory, contact us at engage@gold.ac.uk

Going to the Triangle (my happy place), an LGBTQ+ centre in Deptford.

One of the many happy memories of the borough.

(W19)

If for any reason you wish to withdraw your name or memory, contact us at engage@gold.ac.uk

Some promotional material from the In Living Memory project, Where to, now the sequins have gone?

(W18)

If for any reason you wish to withdraw your name or memory, contact us at engage@gold.ac.uk

An oral history collected by Paul Green as part of the In Living Memory project, Where to, now the sequins have gone?

In the interview, Ian discusses his time performing in the award-winning cabaret act, Katrina and the boy and his memories of the lost gay bars of Lewisham that thrived from 1970s-90s.

Transcript

Rosie (interviewer): OK, so I’m Rosie Oliver and I’m recording an interview today on 12th August at Deptford Town Hall, and I’m speaking to Ian Elmslie. Ian, can you spell your name please?

Ian (interviewee): E-L-M-S-L-I-E.

Rosie: Perfect. And it’s I-A-N.

Ian: I know, there’s only so many vowels a name can have.

Rosie: Yes.

Ian: [Laughs] I-A-N.

Rosie: I-A-N. Brilliant. OK. And the purpose of this interview is for the Avant Gardening Bijou Stories Project: Where To, Now the Sequins Have Gone? which documents the gay bars and communities that existed in the Borough of Lewisham particularly in the Seventies, Eighties, and Nineties. And it will give rise to creative projects that include a podcast which may feature some of the material from this interview. But the interview is also for the wider umbrella programme, In Living Memory: A People’s History of Post-War Lewisham, and an oral archive that’s being developed for that. So that’s the preamble, let’s start.

Ian: Right.

Rosie: Ian, just in a word or two could you just introduce yourself?

Ian: My name is Ian Elmslie, I’m a recently turned 60-year-old performer, author, former teacher, prison liaison officer. Anything where they’ll open a door and have me, and have me chat, I think I’ll go into. [Laughs]

Rosie: OK. And we are interviewing you because you were part of an act. Tell me about that act.

Ian: I was in, 1990, under the – or under the orders of one Lily Savage, I united with an old drama school pal called Katrina, and we formed an act called Katrina the Boy, thinking – you know, Savage has said he’ll get us a couple of gigs, “Oh, we’ll just see what happens, maybe do one or two,” and it became a 10 year career where we took one week off a year. And we were just working throughout the whole of the Nineties. We just worked and worked and worked in every single gay bar that was, and maybe will ever be, but it was an extraordinary time. A very, very special time to be working on the gay cabaret circuit.

Rosie: OK. So before we get into your experience in the Borough of Lewisham, tell me a little bit. Give me a flavour of the act; what was it about?

Ian: [Laughs]

Rosie: What were you doing?

Ian: Well we were – in retrospect, because I had no knowledge of the gay cabaret circuit at the time, you know, Savage spoke about, “Oh, I’ll get you gigs on the gay cabaret circuit,” and this meant nothing to me at all. And it’s only when I started working on it and going to places like the Royal Vauxhall Tavern, and the Black Cab, and the Royal Oak, and The Two Brewers for the first time in my life – I’d never been in them as a punter, the first time I’d ever gone in as a performer. And I realised after a few months how unusual we were as an act, because at the time it was all drag queens, most of them lip-syncing to other people’s songs, and the occasional stripper thrown in.

So to have a loud-mouthed blonde woman singing live and being very funny, and a gay man sitting at a piano not taking his clothes off was at the time really quite revolutionary. And so the first time we ever played venues, when we walked on stage you could see people just going, “What is this? What are they going to do?” And then we gave it to them. Whether they wanted to have it in their lives or not we gave it to. And I think the fact that we were – it was the right time for something new and different and funny and quirky and live. We were completely live which was a big challenge to some of the venue sound systems. [Laughs].

Rosie: So what songs was … Katrina was singing, right?

Ian: Katrina was singing.

Rosie: I mean tell me a bit more about the act. Give me a feel for it.

Ian: There was nothing we would not do. There was no style of music we would not invade and take as our own. Yes, you could have the typical Sixties girl singers; a lot of Dusty, a bit of Sandy, a bit of Mama Cass, blah-blah-blah-blah-blah, but then we would do Cole Porter, and Rodgers and Hart, and Noël Coward. We’d do glam rock. Sometimes we would finish our set with Devil Gate Drive by Susie Quatro. I think the night we finished with Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen you just saw the audiences jaws just go, “What?” Musical theatre we looked at; we did some original songs. Disney Nights we used to do, Country and Western Nights, there was nothing we would not have a bash at if it worked with a piano.

Because all we had was a piano with a built-in drum machine, and so the song had to have strong lyrics, strong melody, it couldn’t rely on arrangements. So we spent a lot of time listening to a lot of songs to find out ones that made us laugh and were topical. We tried to find songs that were possibly going to reflect what was happening in the world at the time.

Rosie: Can you give me an example of a song that you might have sung that had a resonance?

Ian: Gosh almighty. Oh, OK. [Laughs] I mean when Fergie was caught having her toes sucked by someone on holiday, we found the song Popsicle Toes. And I mean you just tried to find songs that – Katrina had a fair old gob on her, and it helped if she could set up the songs in a funny way, and if they were topical. Our first song that we ever did at the RVTR opening gambit was Cruella De Vil which of course we dedicated to Margaret Thatcher with a Phantom of the Opera intro to let them know that this is what we thought about her.

So we would make political jibes and jests, and just observations of what was going on. If we could find a song that was timely, you know taking the theme tune of the old TV show Raw Hide but doing it as if the Pet Shop Boys were doing it. So you’d take this like Rollin’, Rollin’, Rollin Country and Western Song and marry it with a very Eighties disco treatment, and making the audience laugh just with the fact that we’d taken an old song and slammed it up to date. That was a lot of fun to do.

Rosie: Can you paint a visual picture?

Ian: Of the two of us?

Rosie: Hmm.

Ian: [Laughs] Ah, now I will have to pinch a line here from the legendary Victor Lewis Smith who used to write for the Evening Standard. He used to do the television criticism in the Evening Standard. And it was kind of law that if you hadn’t been slated by Victor Lewis Smith you really weren’t anybody because he was caustic. And he once referred to Katrina – he’d seen us on the telly doing a dreadful game show, and we acknowledged that it was an awful, awful game show, The New Mr and Mrs. I shudder in the memory; we had to film 52 episodes in two weeks, it was just – we got paid. But he described her as looking like Gazza in drag, which I thought was hysterical. And she did have very cropped peroxide blonde hair flipped up at the front with a Tin-Tin quiff.

And when we first started working she was a big woman, 16 stone and proud of it, and with a mouth on her. She was kind of so Dawn French met Alison Moyet met Jo Brand, that’s what we’re talking. In your face, took no prisoners. Whereas I was sat very quietly behind the keyboard, and my stage outfits over the years very quickly morphed into me just wearing a vest and jeans on stage. Not for any predatory reasons, that I was trying to seduce the audience, but actually because the venues were so hot that I could just go, “Oh.” And I don’t like things around my arms when I play the piano, so a vest and jeans. And I didn’t have to carry a wardrobe bag either.

Less things to carry; I had quite enough to carry, so it served our purposes that this very loud, colourful ebullient woman was out front making people laugh, and I was slightly removed and quite silent at the back of the stage which occasionally makes you quite intriguing, especially to a gay audience [laughs] thinking – [laughs] and calling – because I was The Boy. Some people didn’t even know my name, so that again gave me a certain mystery. [Laughs]

Rosie: Wow. Fifty-two episodes in two weeks.

Ian: Oh.

Rosie: That sounds insane, but that’s a [unintelligible 00:08:54].

Ian: Yes, but by the end of the day, believe me, five episodes, you didn’t care if they knew anything about each other or not. [Laughs] She used to walk on and just go, “Ooh, nasty blouses.” [Laughs] We didn’t say that; you just thought it. [Laughs]

Rosie: [Laughs]. OK, so moving on to Lewisham, what brought you to Lewisham?

Ian: I moved to this area in 1984 when I was a drama student. I was a drama student in Sidcup, and you just searched for digs that were along the train line that took you into Sidcup. I always felt very sorry for people who went to St John’s, they must have stood on the platform and just watched trains going because it was forever like, “This train does not stop at St John’s.” [Laughs] Poor drama students. But I moved to Lee in 1985 after one year in Chislehurst. I became resident in Lee in 1985 in a shared flat, and that’s when I staked my claim on Lewisham for many years.

Rosie: And was that before or after Katrina and the Boy?

Ian: That was before. I mean I met Katrina at Rose Bruford’s, and so we were friends then, but that was a good five years before we started working together.

Rosie: OK. So before we jump into Katrina and the Boy performing at the local pubs did you know the local pubs here?

Ian: I didn’t. And again, it became a voyage of discovery because you tend to think that you have to go into London if you want to go to a gay bar. Which at the time, being a student, money was tight, and so if you could get into anywhere free you went for it. So I was tempted to go into the London to the Hippodrome on a Monday and Heaven on a Tuesday because I could get free tickets. And as I said, I didn’t know about the Lewisham scene until the Nineties, till we started working on it. Until I went to the Albany Empire in Deptford, and people would talk about The Castle in Lewisham in a way that didn’t make me particularly want to go and visit it I’d say. [Laughs] And that was all I knew of gay bars in Lewisham certainly in the late Eighties. That’s all I knew.

Rosie: So you didn’t know them as a punter, but you did know them as a performer. That’s how you got to know them.

Ian: Yes, that’s the first time I ever saw these places was when I walked in with my gear to set up, and you just went, “Ooh, OK. Flock wallpaper. Marvellous.”

Rosie: [Laughs] OK, so tell me which one had a flock wallp- – I mean tell me which venue can we start with?

Ian: Well, I had to start with where my heart lay and lies which is the Queen’s Arms. I’d known the governor, Joe Thompson, from The Gloucester in Greenwich, that’s when we first met. And he was very famous because he’d won the pools, and that was quite glamorous because you often hear about people winning the pools, but you never actually meet anybody who does. But Joe won the pools. And I think he used part of his winnings, [laughs], I think he bought hairdressers in London called Bonne Arrivée. I think he just invested in places, and I think had enough to eventually lay his feet down in the Queen’s Arms.

And I loved the Queen’s Arms. It must have been the smallest gay bar in the world. It was like being in somebody’s living room, this central bar with this horseshoe bar going on around it. The music was not blasting out because what’s the point, it’s tiny, so it became a lovely place to go and chat with people. It was a very chatty bar, a very family bar, and they did quiz nights going on there. Fiercely competitive at times, really competitive, which is always good to see. And of course we performed there.

And when you played in the Queen’s Arms you didn’t feel like you were going into battle which some venues could be. Nobody was exploring Ecstasy at that time in the Queen’s Arms, it wasn’t that type of place. And nobody was actually out on the pull there. They’d come for a quiet – not a quiet night out, but a safe, gentle, chatty, hopefully fun night out, but it wasn’t necessarily going to end up in them going home with somebody, so your audience for the cabaret was very attentive.

And when an audience is attentive, you can play everything from your catalogue because they’re with you, they’re enjoying it. And if you’re singing a song that they don’t know, it’s three minutes of their life, they’re not going to like go, “Boo” and run screaming out of the building or screaming at you. So it was such a joy to play there. And the bar staff were just an absolute joy because they knew everyone. And everyone had their particular places where they used to sit and stand. I sat by the bar by the flap, down there, and they knew that I would have a pint and a half of Guinness when I came in because I was driving to go there. And that, to me, is the mark of a great bar when the staff know the customers by name and their bevy. There was never any trouble there ever. I didn’t even see a raised voice in their bar apart if they were joining in with the songs. [Laughs].

Rosie: Yes. Yes.

Ian: And I think it did have flock wallpaper. [Laughs] But it was just – so you felt like you were in your granny’s front room, but there was something very comforting about that. It was clean and jolly and so welcoming.

Rosie: Yes, and someone we spoke to last week was saying it was just this real mix of people.

Ian: Oh yes, they were all ages. I mean it’s one of my – I not going to – sorrows – my observations of the scene now that it tends to be, “There’s the Bears’ bar,” or “there’s the Twinkie bar,” or, there’s the this bar, and everyone feels the need that they have to go and be with their group of people, and only them. But I love a venue that that’s mixed, you know completely mixed – ages, sizes, looks, genders, straight, gay, whatever. Bring them in, that’s how we learn about people, and that’s I think how we can change people.

Rosie: Do you have any memorable performances in the Queen’s Arms? Was it Arms or Head? Arms.

Ian: The Queen’s – oh, the Queen’s Arms. Yes, I would hear Josie Thompson, “Oh, welcome to the Queen’s Arms.” He had this incredible voice like Peggy Mount. He just was really down in his gut. And sometimes his introductions to the act would sometimes last about half the length of time that the act were going to be on. Because he liked to big up the Queen’s Arms and say what a welcoming bar it was, and how we have the top cabaret. And you’re sitting there going, “Can we go on now, please?” [Laughs]

But bizarrely enough, my most memorable night of doing cabaret at the Queen’s Arms was with a singer called Jamie Watson. Katrina, towards the end of our time together, was doing quite a lot of TV. She was doing a programme for UK Living called The Sex Files which was taking a lot of her time. We were individuals, we allowed ourselves and each other to do things outside the act. It would’ve been stupid to say, “No, you can’t do that.” And so I started working with – doing the occasional gig with a male singer called Jamie Watson, and we did a jazz set together. A predominantly jazz set together. And I remember my boyfriend at the time hearing us rehearsing and saying, “Who’s going to want to listen to this?” You know, “These old songs,” he said. And I think he was worried that it was just going to die on its arse. [Laughs]

But we did it for the first time at the Queen’s Arms, and to see people standing there and really listening to an old song by Rodgers and Hart, He Was Too Good all mixed into a Bacharach and David song, A House is Not a Home, so you’re presenting this medley of what it’s like when a relationship comes to an end. And people were openly weeping because they were in the venue which was sympathetic to cabaret and was an integral part of the evening. People just think, “Oh, I’m going to just listen to this song that I don’t know.”

And once you listen to words written by Lorenz Hart and Hal David you’ve got proper – this ain’t Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep, these are great lyrical songs that tell our story. And the fact that Jamie was singing, He Was Too Good To Me. It was a gay man, like myself, in trousers, singing specifically about being a gay man, and that’s quite rare, even now, for a male singer to sing “he, he, he, he, he.” Even Elton John was singing “she” for heaven knows how long. It took George Michael a while to specifically sing “he.” So I’d always think it makes such a difference especially to young people in an audience to hear someone singing “he”.

And I remember the response at the end of the evening, and my boyfriend was there at the same time, and I was really pleased, and he was like really stunned at the response because it was genuine, it was warm, and it was an appreciation of music. It hadn’t been a particularly funny evening because they were used to Katrina and I being quite funny, but it was “Listen to these songs, these songs are great songs and they tell our story,” so that it was a big tick in my memory book. I remember that evening with real pride, as I do with the work I did with Katrina very much so.

I received a compliment the other day from a governor of a venue that we used to play at in the Nineties, and he said, “Your act was so innovative,” and that, to me, is a real compliment, the fact that we never did other people’s songs. We were always searching for something new and something challenging, and the audience responded to it which was a big relief.

Rosie: It being in the Queen’s Arms was a very receptive, attentive, sympathetic audience, and you weren’t fighting with them.

Ian: Mm-hmm.

Rosie: I wonder if that’s a segue to The Castle maybe.

Ian: [Laughs]. Yes, believe me, we never did cabaret in The Castle. I don’t think they ever did cabaret in The Castle. The Castle was just – I went in there once with a friend and it was just bizarre because you had to walk through. I mean some venues had a gay night. The Castle had a gay bit, and so you had to walk through the front part of the bar which was the straight section – and we’re talking Catford here – to get to the gay section at the back. So anybody walking through the front bar was – going to the back bar – wasn’t going there for any other reason apart from the fact that that was the gay scene. So to run this gamut of eyes, the ones where I was not shouted at – we were not shouted at when I went in there, I was just aware that we were being looked at. It was like walking through like a haunted house with the pictures in the frames, like the eyes just moved as you were walking through.

But we weren’t disturbing their game of pool. I think we stayed for one drink. If you asked me to describe it, I really couldn’t apart from just thinking I think it was a bit spit and sawdust, just a plain bar. Why the manager decided that it was going to be somehow financially beneficial to him to have a gay back bar, who’s to know. But I’m sure some people have had a jolly down there. [Laughs] I’m not quite sure I did; I didn’t feel the need to return. [Laughs]

Rosie: No. And you never got the piano out, no?

Ian: I never offered my services to entertain the troops, which actually is quite unlike me because I used to play at a straight wine bar in Lee Green called Casablanca every Friday night and got adopted by the pub. And I believe they were electricians, plumbers, interesting crowd, but I became – and I use the words with care, you know, the pet poof. And if anybody came in, you know a stranger – and like because I was making Boy George look plain at the time, and with sequinned gloves, the hair was God knows what, I’d look like I just dived headfirst into the Max Factor counter at Boots, I mean everything was going on. But if anyone gave me grief you would just see these people rise up and stand in front of them and say, “You know he may be a poof but he’s our poof,” which I really liked. But whether that would’ve happened in The Castle, I don’t know, but it did in Lee Green.

Rosie: And what was the name of that act?

Ian: I was just on my own.

Rosie: It was just you. It was just Ian.

Ian: It was just Ian the Poof. [Laughs]

Rosie: Ian the Poof.

Ian: But it goes back to what – that at that time, in the mid-Eighties we’re talking, and in retrospect maybe that did take guts, I didn’t feel like I was doing anything particularly brave at all. Maybe, in retrospect, I was really like putting myself on the line there, but I really didn’t care. And as long as I entertained them, they didn’t mind. They didn’t mind at all. And I spoke to the governor only the other day, and actually got the chance to say, “Thank you very much. At a time when we weren’t particularly welcome in venues, for various reasons, that you invited me to play in your bar. You made me part the family, and you protected me on the very rare occasion if anyone gave me a mouthful.” So kudos to him.

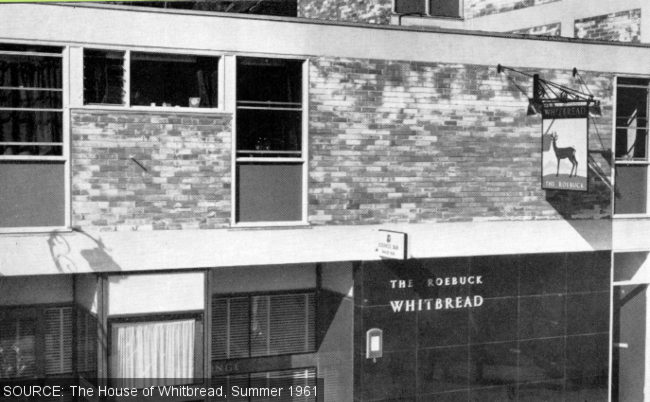

Rosie: Hmm, that’s fascinating. What about the Roebuck? Did you ever perform there?

Ian: The Roebuck I did go to a few times, and that was … Again, you just had to steal yourself a little bit when you went into The Roebuck because everything the Queen’s Arms wasn’t The Roebuck was. The Queen’s Arms was very cosy, very friendly, very gentle; The Roebuck you always felt that something was about to happen, and it wasn’t going to be necessarily pretty. It just had this slight tension going on there. Not between the fellas I have to admit, it tended to be between the women. And that’s not being misogynistic or anything, it was just – it just had that vibe that if anything was going to kick off it would usually be accompanied by a pool cue, and words would be said, and they’d be above an alto key. [Laughs] I never witnessed a full-on brawl, I just heard enough to know that that’s what occurred. And the couple of times I went there, I just felt this isn’t really my place. Not really my place. I’m sure that there were some people there it was their idea of absolute paradise. But for me, get me back to the Queen’s Arms please.

Rosie: OK. But you did perform there.

Ian: Well, we didn’t perform at the Roebuck. I don’t think that even they did cabaret. I think in the vicinity it was only in Lewisham and it was only the Queen’s Arms that did cabaret. And whether that was a financial decision, because you know, they’ve got to pay the act. Whether they thought the punters wouldn’t go for it, I don’t know. And when Stonewall came along – we’d parted professional company by that point – and I know they had a pounding disco that went on in the Stonewall bar, but I don’t think even they did cabaret.

In the late Nineties it was this weird curve, and I saw it coming when the drugs really started to come into the clubs, and cabarets started to become almost an interruption in the evening because people wanted the boom-boom-boom-boom because they were – their pill was kicking in. And so someone coming on and singing a Dusty Springfield song, or saying, “Here’s a lovely bit of Noël Coward,” [laughs] really not quite what they wanted. And certain breweries brought in policies that did not make it easy for acts to perform in pubs.

Rosie: Yes. Yes, that’s so interesting, that dance drugs, all of that, killed cabaret on the gay scene.

Ian: Yes, I saw it happening, it was just bizarre. And I found myself having to dumb down the act. And I choose that phrase with care. You look, you think you’re playing this place on a Friday night, they’re not going to go for the Summertime number, they’re not going to go for anything that’s too wordy, and so we ended up doing – and we used to call it “singy-songy songs.” You know, if they can join in and sing along, as long as we’re still enjoying what we’re doing but don’t get obscure, you just – you know, keep it up, keep it bright, keep it gay because you know that they’re going to not hold their attention.

Rosie: But thinking back to, for example, being at the Queen’s Arms.

[00:26:23 – 00:26:31 – Interruption]

Rosie: For the record, it’s one of the hottest days of the year – of the millennium.

Ian: And going to get worse. [Laughs].

Rosie: [Laughs] Could you give me a ditty, Ian, of maybe something – give me a taste of the act, or maybe like at the Queen’s Arms? Just a line or two.

Ian: What? Oh gosh.

Rosie: Just to give a little –

Ian: Well, for example, now Country and Western, you can’t go wrong with Country and Western. I mean the titles are just so great. You know, what was my favourite country songs? I’ll be Getting Over You When The Grass Is Growing Over Me. It’s brilliant. And I Knew I’d Hit Rock Bottom When I Woke Up On Top of You. I mean it’s just superb. And there’s something so funny about Country and Western which someone described as three chords and a tragedy. But we used to do this Patsy Cline song called Tra La La La La – ting – Triangle. And so we bought a triangle, and Katrina had it, but she did have to say to the audience, “This is quite a quiet instrument, so when I hit the triangle, you all shout “ting.””

So for a start we’d get them bobbing up and down because it’s country – and bo-di-bum, bo-di-bum – so they got to bob up and down. And then they’re shouting “ting.” Then they got to slap their thigh, pretend spitting on the floor. So in one song you’ve got a lot of audience participation going on over a silly little country song that nobody knows called Tra La La La La Triangle. We added an extra verse at the end for gay measure [laughs] to really make the triangle really multi-gender identity. That was quite fun to do.

Rosie: Do you remember the words for that verse?

Ian: Oh gosh. No. Oh, no, I’m ashamed to say I can’t. It’s been so long ago. And there’s one song that we used to do which I’m particularly proud of. Lloyd Webber had just bought out Sunset Boulevard. I’m not really a fan of Andrew Lloyd Webber, and I wasn’t a fan of that show. And one night I just started to do a rewrite of one of the songs from Sunset Boulevard. I’m thinking, “Oh, let’s continue this story.” So it went from that into Three Little Maids from School by Gilbert and Sullivan about these three actresses all of whom played Norma Desmond. Then we went into – Petula Clark took over, so we took Downtown and added new lyrics to that bit. And then we finished off with Take That Look Off Your Face, but change the words to “Take That Show Off The Stage.” You know, so you just played around the lyrics.

And it was a big old song to do; you’ve got four movements in that song to get through, and Gilbert and Sullivan were quite complicated to play, especially when it’s a [Patterson? 00:29:17]. Was it Three Little – Three Little – again, I’ve forgotten the words, it’s been so long ago. [Laughs] But it told the story of this show, my views on it, these three actresses fighting about it, Petula Clark coming in, and then just a commentary about Andrew Lloyd Webber saying, “I must be mistaken, I’m sure … ” Oh, sorry. What was it?

“I must be mistaken, [unintelligible 00:29:43],” but just “But haven’t I just heard that song before? I’m sure it was sung at the end of Act One, Andrew Lloyd Webber I know your score. Take that show off the stage, I can see through your style.” That’s about as much I can remember at the moment.

But plucking up the courage to do that song in certain venues, especially for the first time because you thought, “Are you going to get it?” “Are you?” “Are we going to get it right?” “Argh.” And the first time we did it – sounds a cliché, you know – the roof just blew off because nobody had heard anything like it. And it was clever, and it was funny. So I’m proud of the rewrites that we did. But sometimes what you really enjoyed seeing people do was just sing along with a song that maybe they hadn’t heard for a while. You know, It’s Getting Better by Mama Cass, it’s a great song and it was a great opener, and it was such a positive opener.

And as an observation from the Nineties, with everything that was going on in that decade that had been birthed in the Eighties but just exploded in the late Eighties and Nineties, I think every cabaret act realised that they were responsible for being the tonic for the troops. That we could actually walk into a bar and go, “Yes, I know there is all this crap and shit happening outside that is awful, but just for three hours we’re going to stand inside a bar and we’re going to have a bit sing, and a bit of a drink, and a bit of a dance, and then we can go out and face it again.”

But I think we all acknowledged at that time, “Keep it up.” You know, we weren’t going to sing tragic songs at the time, so to see an audience at that time singing along with What’s New Pussycat, or our favourite – because I’m a lifelong Donny Osmond fan. Donny Osmond changed my life. And when we used to encore with Puppy Love, and you would sing the first line, “And they called it puppy love” and then you couldn’t hear the rest of the song because the whole audience was screaming. And seeing these great burly men going “Aaaah,” and reaching their arms out to the stage as if they were Osmond fans was hysterical. Hysterical.

And that’s my joy of remembering, of having that ability to reach inside somebody’s nostalgia buckets and pull out a pearl and go, “You haven’t heard this one for a while, have you?” and now you are free to scream as much as you like, then go out and finish the shit in the outside world.

Rosie: Ian, what you said, I just loved, and then someone sort of put their – I don’t know what it was.

Ian: A cleaning device.

Rosie: A hoover or something. [Laughs] And of course, everyone can hear the words perfectly clearly, but I just wonder, would you mind awfully just making that point again about – you know, you were saying about the context being the Eighties, and perhaps just to clarify for people who don’t know about the politics of the Eighties and what was going on, and how it was a refuge to boost morale and that kind of thing.

Ian: Oh, god, yes.

Rosie: Would you mind awfully?

Ian: Of course not. I mean during the Eighties, and being right at the forefront of – we started the Eighties with such hope. There were groups like Bronski Beat and Culture Club, and I mean even it was a few since Tom Robinson who was such a hero of mine, but it just seemed like there was this change, and people became more accepting. And a lot of straight people had now gay friends, and they were embracing us. And then – wroooom – in comes – and let’s quote those damned papers, The Gay Plague, and all that fear rose up again.

And Thatcher, and of course Section 28 was just driving us back and back and back. And all that progress that we had made just seemed to be being whipped away from us. Which is why the pubs and clubs became so important because they became, “This is our space, this is our home, and we need each other at the moment.” And that the overused word – phrase, rather – “gay community,” I really started to feel it, that we realised that nobody was going to fight our corner for us, we had to stand together and shout together. And I was really lucky at the age that I was that Tom Robinson Band taught me that, yes, I could be gay and angry that I didn’t have to have this victim label on my forehead. I was allowed to be angry and shout about what was happening.

So going on the Section 28 marches, and fighting for, you know, when they dared not to give us an equal age of consent. They compromised and gave us 18. And I remember an unusual ally, Edwina Currie, at a protest meeting in Trafalgar Square, saying “That as a woman, if someone told me I could have some but not all equal rights they’d walk away bleeding.” And I thought, “Good on you, girl. Good on you.”

But then in the Nineties, when I started working in a scene that I didn’t really know about, but that we were so embraced by so warmly, and you felt the responsibility at that time to provide people with a distraction, a release, a relief from all those headlines, all the funerals, all the grief that we were going through at the time. So just for a few hours we could stand in a pub with a drink, having a laugh, having a sing-along, having a bit of a dance, and it was like topping up your battery. It was like, “Right, I can go out and take another week of Daily Mail-isms and stupid ignorant statements because we’ve been topped up. I’ve had my battery topped up; I am not alone,” and that’s all we need to learn in life.

And it’s such a journey for every gay person that we go through, and every gay person still goes through it now. People say, “Oh, it’s so much easier now,” but as a former secondary school teacher for 15 years, and the number of students who came out to me – I was an out, gay teacher, who are they going to come out to, me. But seeing them do that walk across my classroom, and I know what they’ve come to say, but they have got to say it. They’ve got to have that elevator coming up from their gut which feels like you’re being sick, and – to say those three words.

But at that time, nobody – we all need to feel that we are part of a community, and that people have got their arms around us. And in the Nineties, from my position on the stage, which was such a privilege to see, and seeing people supporting each other. And believe me, I saw people becoming more ill over … If we were playing at a venue, say, once a month, you would see – you would see a deterioration in people. And it fills me up now. And then one week they wouldn’t be there. But to see people standing with them, and holding them, and cuddling them, and for them to come to the dressing room and say, “Oh, you really made me laugh tonight. I love that song.” Blah-blah-blah-blah-blah. And that might be the last time you ever saw them, but you know that you have done something at the time when we felt that people weren’t really – they weren’t helping us that much. We had to find that within our community.

And that’s why I will always support my local bar. I won’t go into town, I’ll go to my local bar, that’s my tribe, that’s my chair, this is the place that I want to say, “This place has to stay open.” Because there is somebody down the road who is plucking up the courage to come in here for the first time, and they’re probably standing outside the door now, looking at the door. And we’ve all done it. We’ve all done it. And if they hear laughter, or if they see – they hear people singing along, chances are they’re going to go in because they think, “I will be safe here.” You know that whole Evan Hansen that’s going around at the moment, you know, “You will be found.” Very clever thing to use as a hook for that musical. “You will be found.” Because there’s a whole generation now thinking, “Where do I belong?” “Where are my people?” “Where will I be found?” And we find them.

Rosie: OK, so we’re back in the room. The battery just ran out and we’re back in the room. And I was just explaining, Ian, how there’s two sides to this project. One is memories and reflections on that scene which you’ve shared with me wonderfully, and the other is – I mean the name of this project is Where To, Now the Sequins Have Gone? And I wondered what you feel now about what’s available.

Ian: Oh, that’s an interesting one. I think we are possibly sitting in front of the biggest buffet in the world, and we don’t know where to start. I actually showed a friend of mine the other night the number of flags that there now are, and the number of titles for groups that they now are, and three-quarters of them I don’t know what they mean. I love the fact that I apparently am now labelled. I’m a demisexual. Do you know what a demisexual is?

Rosie: No, I’m intrigued.

Ian: No.

Rosie: Tell me.

Ian: And there’s even a flag; they’ve designed a flag. A demisexual is someone who can only have a sexual relationship with someone with whom they’ve already formed a strong emotional bond. So in other words, no cruising, no cottages, no sauna, no, that’s never been my way and never will be. But I love the fact that somebody somewhere has come up with this label and designed a flag. Not asked me. I would’ve had paisley all over it. But I worry that people are searching for an identity and there is almost too much choice.

I had a brief [unintelligible 00:40:36] as a school governor, and all girls’ school, and they had a Pride group within the school which I thought, “Ooh, that’s pretty impressive.” And they invited the gay school governor to come and see one of their meetings; of course I went along. And I sat next to this 12 year old girl – so we’re talking Year Nine – and I know Year Nine. As a teacher, I don’t know, they hate everything – they hate themselves, they hate their parents, they hate school, they hate the world because they are a mess of hormones. And this girl was having an open argument or an open heated debate with herself about whether she was lesbian, bisexual, polysexual, or asexual.

And I couldn’t help but think, “You’re 12. You’re 12.” And it’s the only time I ever put my hand up in the meeting, because I was there to observe. And I put my hand up and they went, “Ooh, ooh, Mr Elmslie,” “Yes,” and I went – and I just looked at her and I said, “You will know when you fall in love with somebody. That’s when you know who you are.” Because it’s not about what you are, it’s not about the label. You have fallen in love with someone and that’s when you will know. It might not last, it might be love that only lasts a year before you discover another part of yourself.

But I think I worry that there is so much emphasis or now who am I – what am I, and I think people are losing sight of who am I. I identify as Ian; I’ve identified as Ian since single figures. I knew I wasn’t like other boys. From the earliest I wanted to be a ballet dancer at the age of eight when I should have been wanting to be a fireman. I knew. Being an Osmond fan you didn’t say that on the playground; I did. I came out when I was 16 at a boys’ public school in the mid-Seventies. [Laughs] That took some guts. But I’ve never felt the need to brand myself apart from this is who I am. If I choose to wear makeup, which I still do, does that make me gender fluid or non-binary, no, it makes me Ian on a Friday because I want to do it today.

And I know it is necessary, I know it is, and everyone is going to find their pathway to who they are. I just worry that it’s an ever increasing maze at the moment that it could occasionally lead to a dead end when it sometimes simplify. Edit. Edit your life, [laughs] as you said about writing a book, but which I know, but everyone is on their journey. And whatever anyone has to do to get them to the person that they need to be – not wants to be, that they need to be, that they have to be – do it. Do it. Explore, experiment, call yourself a … That’s how I see things at the moment. But then I think, “Oh, am I just old.”

Rosie: Well I think it is a big question that people of all generations are asking, aren’t they?

Ian: Hmm.

Rosie: And I think we’re all reflecting on our pronouns and all of that. But I guess slightly swerving back towards the bars, I guess one of the questions that we want to ask with this project is finding out about the role that those gay bars like the Queen’s Arms had for people in a really tough period – particularly the Nineties as you said; the Eighties and Nineties – they’re all shut; most of them are closed down now.

Ian: Yes.

Rosie: And what has that done to our sense of community, a), and b) what’s the impact on us as individuals?

Ian: Like too much in society it’s pushed people towards their phones. You know, everyone is just now face down, face down over a phone all the time, and often their lives are focused on their phones. And it makes me sad, and the one local gay bar that I do still go to, the George and Dragon – which I love. I love the George and Dragon. I’ve known the governor 30 plus years. Salt of the earth. Still puts on cabarets. He’s a great, great man. So much time for the duchess. But there will be that time like you see people on their phones, sometimes even when they’re with – in company. And you think, “Turn it off. Look up. Look up.” But the loss of the local gay bars I think is incredibly sad.

Of going to a pub where it is your space and you do feel safe, and you can have a drink, and play pinball. I used to love playing pinball in The Gloucester in Greenwich. I loved it. Having a quiz, having those things that are not what I call the Kleenex Syndrome where you pick people out of a tissue box and blow your nose on it and then throw them away. I think this whole – making anyone – I loathe this disposable society that we’re into, and it’s not just things, it’s people as well. It’s like, “Oh, you’ll do for the night.”

And that’s harder to do if you’re going to a pub and you’re seeing the person that maybe you were a little bit offhand with the previous night, thinking, “Well I’m never going to see them again because they were just on my phone,” and actually they’re drinking over the other side of the bar from you, and they might be next Thursday, and the night after that. So in a way you almost have to modify your behaviour, and get some social skills going on in there, and not treat people quite so – oh, callous is the wrong word, and cold is the wrong word, but actually take some time to get to know people. Go back to a bit of old dating. That beautiful flirtation that used to happen in bars where someone catches your eye, and you spend about five minutes pretending not to catch theirs, and just looking at every part of the room apart of them.

Then you think, “Right, I’ll have a go,” and hopeful that you’ll get that quick eye contact back again, and then, “No, I’m not looking, not looking.” And then it might be a little bit longer, might a little bit of a hint of a smile, maybe the raise of a glass even, and that’s when you know you’re in. And that beautiful dance of dating that happened in bars doesn’t happen anymore, and that’s such a shame because you’re just judging people by statistics. It’s like the old Victoria Wood sketch about Hellmann’s mayonnaise. “Now are you happy with your wash?” You feel like you’re just filling in a checklist, and you get to that survey and go, “Oh no, sorry.” “Oh, if you’re five foot six, no, sorry.” But that five foot six might be the person that makes you happy for the rest of your life.

Rosie: Yes. Quite. Yes.

Ian: It’s quite bizarre. And so I miss the very personal – you know, when you’re sharing the same air, sharing the same space as people. And the fact that the venues have gone one by one by one by one is really sad. And I worry that the young people who think that they might have to behave a certain way, that they might have to go into town and into Compton Street, and go to G-A-Y, and have to wear a crop top, and have to have a belly button ring, but “I’ve got to be like this,” because I look around and there are so many people here, and “Oh, I’ve got to look like them,” when in a smaller venue you didn’t have to do that, it was much less pressured. So I worry. [Laughs] I worry. [Laughs]

Rosie: And I wonder if there’s a generation thing as well. You know, I mean because partly what’s coming across to me is a slightly beleaguered older generation feeling that our venues have gone, our pronouns are all in question –

Ian: Hmm. Sometimes bad grammar.

Rosie: [Laughs] Sometimes there are apostrophes in all the wrong places.

Ian: [Laughs]

Rosie: Plurals and singles. And you know, “Where’s my place now?” Do you feel that?

Ian: Ooh, I’ve always felt like an outsider, always. And even when I was really at the heart of the gay cabaret scene I always felt like I was slightly outside of it. You know, because Katrina was the front woman, loud, blah-blah-blah-blah, and I was this the piano player, and so people inevitably talked to her. Maybe about me, sometimes, because I used to drive her up the creek. She’d say, “I’m not his dating agency.” [Laughs] But I’ve always felt that I was just slightly outside of things. And that might be choice; maybe I’ve chosen that as well.

I think sometimes I prefer looking and observing rather than being right at the heart of it. I’m going to plug now; it’s why I called my book A Marvellous Party because I felt that I’d been invited to this marvellous party where all of my heroes – everyone that I looked up to and idolised since year dot – were in the same room and I got to meet them. I got to meet … But it wasn’t about me. It’s almost like I was standing at the edge of the party going, “Wow, aren’t I lucky to be here?” As opposed to the person swinging off the chandelier or dancing on the table, I’ve never wanted that. But as I age, I am quite content to still be an outsider.

What I object to is being made to feel like an outsider by a community that I’ve battled really hard for. Because over lockdown I had no excuse but to record an album of original songs – loved it – called Old Boyfriends. Very specific songs about old boyfriends. A lot of them very funny, some of them bit more poignant. Composed it, recorded it, released it, everything. Got some lovely gigs above The Stag Theatre Bar which now is permanently closed. You know, our one LGBT specific theatre space in London has had to close its doors.

But all these venues who say, “We are all about inclusivity, we are all about celebrating diversity,” not when you are 60, you write your own songs, you perform at the piano, and you do them in trousers. Not a hope in hell. No one will give me a gig. If I was doing it in a dress and singing all that jazz, like they all do, I’d get a gig. But it’s just very interesting. Whether it’s ageism, whether it’s the fact that I wear trousers, whether it’s original material, I don’t know. But not offered a gig, even with my history, and that’s interesting. When you are made to feel that you don’t belong by your own community that’s tough.

And I do like seeing theatre. I saw a play recently called Riot Act, Alexis Gregory, verbatim theatre, three characters – one an original Stonewall Bar survivor, one drag queen probably in his, say, Seventies, Eighties, and one an actor activist – and all giving their perspective of standing up and making a stand. And one of the characters is just saying, “You young people, if you see an older person in a bar, go up and talk to them. Find out where you came from. Find out your history. Because they did a lot of marching and a lot of shouting and a lot of demonstrating, and put up with a lot to enable you to have the freedoms that you enjoy which you probably still moan about and say you haven’t got enough.”

But if you can walk through the streets of London in a miniskirt, a lot of people did a lot of work to do that, so go up and talk to them. Don’t just leave us sitting in a corner, thinking, “Oh, there’s flies buzzing around their head.” [Laughs].

Rosie: Yes, and I think that goes to the whole topic of that intergenerational connection and conversation, and where can you have that.

Ian: And I don’t know. I don’t. And when bars and communal places go, you don’t go there. I mean it is interesting at The George, there is a real mixture of ages that go in there. And it’s a very respectful bar The George and Dragon, and that’s all down to the governor. And the fact that cabaret still goes on. I think cabaret, bizarrely enough, is such an inclusive thing, you know, encouraging people. I think it was Joyce Grenfell, who I adore – adore her – she said that when she used to sing in wounded troops hospitals when she was – during the wartime, and she said that “what people really want in times of trouble is to sing together, quietly.”

You know, if they’re lying in the bed, you know, it’s why We’ll Meet Again is such a prominent song. It’s not vocally taxing, it’s not Roll Out the Barrel, it’s this very gentle melody. And sometimes when I see the drag queens in bars singing a song that everybody knows, and see people singing along, it’s such a beautiful thing. And more of it. But when these places disappear, that feeling of, “Oh, we’re all singing together,” goes, and I’m singing next to somebody who doesn’t know all the words, but I only know the chorus. “Wow. You know more than I do. You’re older than I do. How’d you do?” You know, have a chat. Have a chat. So important. So important.

But we’ve got reach out our hands to people. And vice versa. But, again, I was so lucky in schools. I spent my day – [Laughs] I know some people might think this as purgatory – with teenagers, [laughs] you know, with all their stuff. And they were always – they could ask me any question that they liked. They had an out gay teacher; they could ask me anything. I remember this one lad in Year Nine asked me quite a personal question and I answered him. And he went, “You’re not embarrassed at all, are you?” I went, “No,” because I haven’t been embarrassed since I was 10.

I felt sorry for the people who weren’t like me in a way because I’m going to have way more fun than you. [Laughs] Thank you, David Bowie, who pointed out that screen and said, “If you are an outsider come and join my gang because we are going to have so much fun.” We are going to have so much fun, and thus we did. But yes, I will always have this desire within me to let people gently know what they don’t and maybe they should.

I love going into prisons and reading bits from my book to a book club of prisoners in Thameside Prison. It’s great, but you ask them about their heroes; “Who’s influenced you?” “Who would you like to have dinner with?” “Who would you look up to and think, “wow, I’d really like to meet you?”” and then you read. And it is just one of the most rewarding things when you go into a space where a lot of people wouldn’t go and think, “Oh no, they’re going to get to me, they’re going to be horrible to me,” and they’re not. Because we all want to learn about people, and so we should, but in bars, in clubs, you got that opportunity.

If you’re standing next to somebody, ordering a drink, you might spark up a conversation and – shock horror – make a new friend that lasts, that lasts your life. And again, that’s another legacy that will be lost by bars going. I worry about longstanding life-enhancing friendships that were forged in bars. I bumped into my favourite barmaid from the Queen’s Arms the other day, Zara. She’s with a girlfriend now, they’ve got a baby together. We will be buddies till the day we drop, but if it hadn’t been for the Queen’s Arms I never would’ve met Zara. Never. I never would’ve met her beautiful son.

And you know, she shouts at me now, and she calls – because we used to joke about having a baby together; I was sperm, she was womb. I’d walk in, “Hello sperm,” “Hi womb.” [Laughs] The baby’s going to have fab hair, she’s got these fabulous ringlets that used to come down to her [unintelligible 00:57:29]. [Laughs] But now she has got a baby, you know, and so the other day, walking home to where I live, what do I hear from the other side of the road, “Oi, sperm.” [Laughs] I do hope some granny overheard it and went, “What? Where?” [Laughs]

But these friendships that were formed – and talk about the Queen’s Arms, when Joe Thompson died – and it’s damned near an anniversary that he passed away – and that turnout at his funeral filled the entire church in Hither Green. You know, both floors of Hither Green and it was standing only. And then there was a wake drink in the Rose and Crown in Greenwich. And it is wonderful seeing people that you hadn’t seen for decades, because once that bar closed, like any bar closes, people dissipate because it was the one place that people used to come together.

It’s like when The Cheers bar closed, where did those people go? And then suddenly we’re all in the same room again, and we’re greyer, and we’re bigger, but you look in the eyes and the eyes do not change. The eyes never age. And to see these people again, under such sad circumstances. But he pretty much individually created that beautiful space where people could meet and make friends for life, and that’s the loss of … If bars disappear where do people go? We lose our alternative living room.

Rosie: Wonderful. A sad point to end on I think. [Laughs]

Ian: [Laughs] I think I should make a joke now. [Laughs] [unintelligible 00:59:14] a filthy gag.

Rosie: Because I think for completeness, you did mention your book, so do you want to just say a few words about it?

Ian: Oh, I had to.

Rosie: What it was, what it’s called and everything.

Ian: My publisher [laughs] will never forgive me if I …

Rosie: Yes, quite.

Ian: I’d left teaching, I’d lost my brother under the worst circumstances, I was completely flat-lined. I love my job, and I just didn’t know what I was going to do next. And a week after I finished teaching, Cilla Black died, and I just – and I’d been with her six weeks previously at Paul O’Grady’s 60th birthday party. And it was the second time I’d been in the presence of showbiz royalty. And so I just wrote this thing about what it was like playing the piano in front of Cilla Black because she’s seen everything. And when you’re looked at by Cilla Black you know you were looked at. And people responded to it, and they said, “Oh, that’s really good. That made me laugh, made me cry, made me think.”

And I thought, “I’ve met a lot of famous people. Let’s just write. Every Saturday let’s write a ticklish remembrance of meeting somebody famous.” But I realised I was writing about my heroes. I was writing about meeting Donny Osmond, meeting David Bowie, meeting Quentin Crisp, Tom Robinson, Armistead Maupin, George Michael, Boy George. Yes, I know, it’s bonkers. And all these people who, in my little outsider land, had just – what I call – thrown down the trail of breadcrumbs. You know, when you’re lost and someone says, “OK, you’re lost, come this way. Come this way. I’ll guide you out the woods.”

And so each chapter was, you know, “The day I met Quentin Crisp,” “The day I met Boy George,” “The day I met … ” blah-blah-blah. And I only realised about three-quarters of the way through that I was writing a book, and also I was writing – because the centrepiece is about the Nineties and working on the gay cabaret circuit, and realising that I was writing a period of our history that could be lost if it wasn’t written down, because so many people who should have written their stories didn’t. They died, or just never found the time or the wherewithal.

And so I wrote what I call a 320 page thank you letter to my community, to my heroes, called a Marvellous Party. And it’s about how, again, we can’t get through this life on our own. We are not strong enough; we need people, whether they be friends, whether they be celebrities, to help us along the way. We can’t do it by ourselves. And I’m so gratef- – and to have the opportunity to say to these people whose records I’d heard, whose books I read, “You changed/saved my life. You gave me a clue how to survive public school, how to survive my parents’ disapproval, how to become better at my job, how to become a better teacher, how to become a better communicator.”

You know, we are permanently in a classroom through life, I think. We are reading, we’re listening, we’re seeing, looking at art that goes, “Wow, that’s a life altering thing.” And I never intended to write a book, but I’m jolly pleased that I did. And my favourite [of you? 01:02:45] – and I will finish with this line from a fellow drag queen of the cabaret circuit, the wonderful Miss Millie Mop who looked like seven foot of Marge Simpson in a blonde beehive – and he said, “You’ve written down what the rest of us were too drunk and drug-fucked to remember,” [laughs] which is the best review ever. [Laughs]

Rosie: Excellent. Well, we can end on that.

Ian: We shall.

Rosie: [Laughs]

Ian: I gabble away.

Rosie: Wonderful. And I don’t know if I caught this on tape, I don’t think you did actually – talking about being drunk and drug-fucked – and you, as a performer, were seeing this sober.

Ian: Completely.

Rosie: Yes.

Ian: Yes, we just didn’t drink on stage. I just couldn’t have done my job as well as I wanted to if I’d been remotely sozzled. So, yes, I was taking it all in. I’ve seen people at their best and their worst. [Laughs] But of course I don’t remind them – much. [Laughs]

Rosie: Excellent. Well, Ian, you’ve been an absolute star.

Ian: I’ve loved every minute. [Laughs]

Rosie: Well, I’ve loved every minute. Thank you. Really. Wonderful.

Ian: My pleasure.

Rosie: Thank you so much. So unless you have anything else that you’re burning to say.

Ian: [Laughs] Love each other, just love each other. Please, please, please love each other.

Rosie: Love each other. Get that, Goldsmith Archive. OK, I’ll press stop.

[End of recorded material at 01:04:08]

(W17)

If for any reason you wish to withdraw your name or memory, contact us at engage@gold.ac.uk

An oral history collected by Paul Green as part of the In Living Memory project, Where to, now the sequins have gone?

In the interview, Richard discusses his memories and experiences of the lost gay bars of Lewisham that thrived from 1970s-90s.

Transcript

Rosie (interviewer): The day, today’s the 8th September, and this is an interview with Nick. Nick, can you tell me your full name and spell it. Spell your surname.

Richard (interviewee): It’s actually Rick. Rick Stableford, R-I-C-K, and Stableford is S-T-A-B-L-E-F-O-R-D.

Rosie: Rick.

Speaker 3: Thank you. [Laughs].

Rosie: Sorry about that.

Speaker 3: Start with what’s your name.

Rosie: My name’s Rosie Oliver, and this is for the Bijou Stories: Where To, Now The Sequins Have Gone? exhibition and the archive at Goldsmith. So I’m going to really train the mic on Rick.

Speaker 3: [Laughs].

Rosie: And, Rick, if you could just introduce yourself, and what brought you to the show today?

Richard: Oh, right, so yes, I’ve lived in Lewisham for about 40-odd years and seen many changes. And a flyer was given out for the Drag Race, and that’s where I first heard about it, and so I came. So, yes, I investigated and found out. I literally only live just up the road, so I came down to have a look around, and also to volunteer because I think it’s good to give something back to Lewisham, isn’t it, you know.

Rosie: Yes. And obviously you have some memories of the gay venues in Lewisham, and I wondered if you would share some of those. I mean which one was the one that you’d go to most often?

Richard: Oh, I think one of my favourite memories was when I first came to Lewisham there was a group called the Gay Men’s Drama Class which was an adult education class run by [ILEA? 00:01:45] in the London Education. And I got to make friends here, and through that class, and we used to just scream about, you know what I mean, it was so much fun. And I remember there was a gay disco at The Albany, and the guy who ran the class also set up that disco. And one day he – I don’t know how, we all went round his flat, and we all dragged up [laughs] in the most sort of charity shop drag. It wasn’t particularly good; it was just like slung together drag. And we all put makeup on each other and things like that.

And [laughs] like there was about five or – no, it was probably about 10 of us in all, and we just paraded up Deptford High Street in drag in the late afternoon, walking up. And I just remember it as a really happy moment thinking, yes, “We’re here, we’re queer,” or whatever, so walking to this disco.

Rosie: Do you remember the reactions you were getting from people in Deptford High Street?

Richard: I don’t think I really looked for many reactions. I avoided eye contact I think. I can’t remember, we were just supporting each other and having a laugh with each other really, you know what I mean. People got out of the way, [laughs] I remember that. We were a group walking up, and that’s one of my – probably – you know, it kind of I felt I have arrived in Lewisham kind of feeling, you know what I mean. It was it was good, yes.

Rosie: And when was that roughly?

Richard: Oh, it’d be about ‘88-ish. Around there. ‘88? Yes, it would be ‘88 I think, or ’87. ‘87, ‘88, that kind of time. Yes. Yes.

Rosie: Excellent. So did you go to any of the pubs either with them or with other people?

Richard: Yes. Yes, I went to lots of pubs. It was like, yes, I went to all of them really. It’s like, yes, I’ve seen them all come and go over the years. It’s like even the ones that only lasted a month, it is like, yes, I went to all of them. Some I preferred more than others, but some stayed later – stayed open more than others, so they – [laughs] I went to those as well. So it’s like, yes, depends on whether they’re selling alcohol really. [Laughs]

Rosie: OK, so can we run through them? Which one do you want to start with?

Richard: Oh, well, in Lewisham of course there’s The Castle, Stonewall, 286 or whatever it’s called, 186. Was it 186 or 286?

Rosie: 286.

Richard: 286, that’s it. The Castle, The Queen’s Arms. Oh, there’s The Phoenix of course, and what other ones were … There’s ones in Catford as well that have come and gone. And there used to be a nightclub on Forest Hill, wasn’t there, for a while. And yes, they’ve all come and gone, but I think probably it’s The Castle that was the one that I loved, you know what I mean. Yes, it was a good local feeling there, you know.

Rosie: OK, so I never went to The Castle. Paint a picture for me as to what it was like.

Richard: Yes, as you may know, it was straight at the front and gay at the back, and so you had to walk past the pool tables and run the gauntlet really. [Laughs] To think, “Oh my God, I’ve got to be with my people in the back.” And in the back I remember it as curtains you walk through, I think, but I could be wrong. I think maybe they came a bit later, maybe. And at the back it was – yes, it was a disco or – and it was just people sat around on tables, smoking in those days. And yes, smoking drugs even, you know what I mean. It was like, yes, it was a very relaxed atmosphere, and yes, and people just got on, it was good fun, although there were fights. [Laughs]

And the fights, there was always a fight, and nearly every other night [laughs] something – it was like – and, yes, if someone had probably looked at the wrong person, or whatever, over the time and it would be like some slappy fight going on. Yes, it was usually over as soon as it started, you know what I mean. It wasn’t huge fights, but it’d be like a couple of broken glasses, and you’d think, “OK, we’ll all move down this end of the [laughs] bar,” you know. But that gave it an edge which made it exciting, you know. Yes, I liked it.

Yes. The Ship and Whale as well. You remember The Ship and Whale as well? That was a gay pub for a while, yes.

Rosie: Where was The Ship and Whale?

Richard: That was in Rotherhithe. Yes, yes, that a fun pub. Yes, I used to know – I went out with the barman there. And also Goldsmiths Tavern. I always remember going to Goldsmiths Tavern actually. First time I went there I was [laughs] – there was this – I think it’s the first time I saw a male stripper in London, [laughs] and I’m like … And I was chatting to my mate, we were on the bench chatting away, and I wasn’t really – the stripper was taking ages taking his clothes off, so you got bored. You think, “Oh, come on, get to the exciting bit.” So I was chatting away to him, [laughs] and then the next thing I knew there was a foot on either side of me, [laughs] and this package slapping against my face. [Laughs] I was saying, “What do I do? What do I do?” It was very funny. It was very funny, you know.

Rosie: Is that tea-bagging?

Richard: No, it wasn’t tea-bagging, he still had a leather thong on. It was the leather thong that was slapping against my face. I was thinking it’s very funny.

Rosie: OK, where else was … Did you go to The Queen’s Arms?

Richard: Oh, yes, The Queen’s Arms was literally my local. I lived – well, I still do live about two minutes from it, and I used to treat it as my front room, basically. [Laughs] I always remember during one particularly bad splitting up with a boyfriend scenario I used to go there after work and drink, [laughs] have a drink, and I couldn’t be bothered to go home. And I used to drink till about 11 o’clock at night [laughs] and get really drunk. And yes, and I’d go home, fall asleep, wake up in the morning with a hangover, and Cinders – do you remember Cinders? Yes, you would. Cinders used to phone me up and say, “You left your work bag here again,” [laughs]. So I used to have to pick my work bag up, going back to work, [laughs], go to work, come back, and do it all over again the next night really. [Laughs].

Rosie: Now was Cinders – because I thought Cinders was barman at The Castle, but was he? You said you left your bag here. Was he the barman at The Queen’s Arms as well?

Richard: Yes, yes, he did The Queen’s Arms. He was a barman at many. There was also a very short-lived gay pub up near – you know where the BP garage is, it’s up around the back there. I can’t remember what it was called, it was very short-lived. He was a barman there as well. But I was actually – when I first came to Lewisham he was my neighbour, just by chance, you know, just coincidentally. And I was working as a teacher at the time, and I used to come home really tired, really – you know, it was hard work. And he’d always shout, “Rick,” [laughs] whenever I walked – and he just cheered me up every time. You’d kind of think, “Oh, I am home,” you know.

Especially in those days it was Clause 28 and all that stuff, and you felt bit oppressed really, you know what I mean. And so it was nice just having a camp gay welcome when you walked past his flat. Yes, it was nice.

Rosie: Yes, because I’ve heard someone else talk about him shouting out from the window above the – was it the Admiral Duncan up in Compton Street?

Richard: Yes, yes.

Rosie: Yes. So I just like this idea of this projected voice. [Laughs]

Richard: Yes, so he had a very loud projected voice, yes, he was always welcoming. And yes, he used to do champagne breakfasts before Gay Pride. And because he was my neighbour he used to always pop down and have a bucks fizz or something, you know what I mean, and wish everyone a happy Pride before trolling up to London or Brighton, wherever it was.

Rosie: And tell me about the Roebuck.

Richard: Ooh [laughs] that was a seedy place, really. Yes, it smelt. The first thing that got you was the smell. It smelt like your worst public convenience really. [Laughs] And it had the more rent boy side to it, you know what I mean. It was very Eighties in décor, it was all pink and greys. But towards – I think it closed, what, about 10 years ago maybe, or maybe a bit longer. Anyway it went to be The Phoenix, and closed, and it still had the same décor, you know, like that piney pinky-grey stuff, and it really got grimy and horrible.

The great thing about it though was downstairs was a disco and it would stay open until four o’clock in the morning, you know. And so, yes, when all other pubs have failed you can always go there for a last – a late night drink, you know. And I remember [laughs] taking my – we had a work’s night out, you know me with my straight colleagues. This was when I wasn’t a teacher, I had another job, and I took all my work colleagues there because it’s like, “Yes, let’s go for another drink. Yes.” And they all loved it, we had a great time there, it was a fun night. It was their introduction to the Lewisham gay [laughs] scene was The Roebuck.

But the last time I ever went there, I went there with a mate of mine and you knew it was on its last legs a bit because the – like we were playing pool, me and my mate, and the landlord came up to us and said, “Oh, we’ve got your membership cards.” And we’re thinking, “Hey, what membership cards?” You know, we never applied for it or anything. And he gave us two random membership cards for these two people that we’d never heard of, but I suppose – but it apparently let us in whenever we wanted, or let us in without paying admission or something, you know what I mean. And you knew that that was the last, you know, because why would they give us this? I think they were really desperate.

Yes, yes, it was a shame it was shut down because it was a bit of an institution, but a sleazy one really. A smelly one really. I just remember the smell was – yes, you didn’t want to use the toilets there. [Laughs]

Rosie: Can you tell me about a big night out where you’re going from one place to the next in Lewisham?

Richard: Oh yes.

Rosie: Did you have those?

Richard: Oh big time, yes.

Rosie: And tell me about the sequence and what would you be doing at each different place?

Richard: All right, yes, well it’s like the big night out. It was great because you used to get the bus to Greenwich –

Rosie: From?

Richard: – from Lewisham. Yes, get the bus to Greenwich. You’d start off at The Rose and Crown or The Gloucester. It was The Powder Monkey as well there, wasn’t there, for a short time. I never really liked The Powder Monkey; it wasn’t my scene. But you used to do the trolling between The Rose and Crown and The Gloucester, and then go to – oh, what’s that one? Oh the one on Blackheath Hill. George and Dragon. Yes. Sorry. [Laughs] And see the drag act there; that would be about 10, 11-ish. And then from there go on to either The Phoenix or Stonewall which would be open till three or four in the morning, you know what I mean.

Rosie: Stonewall was what became of The –

Richard: – Castle.

Rosie: Castle.

Richard: Yes, yes, yes, yes.

Speaker 2: [unintelligible 00:14:27].

Richard: Yes, Stonewall became The Cas- – The Castle became Stonewall, yes. Yes, so, yes, it would be like a – you know, the chatty social bit of the evening would be at The Rose and Crown, The Gloucester, and that was a great time because you’d troll between the two pubs. They’re literally only 50 yards apart, aren’t they, and so you’d see everyone in one and, “Oh, I’ll see you in a bit,” and you’d see them in the other one. I tell you it’s almost like a soap opera; same people but in different combinations in different pubs, you know. And then you’d see a bit of show at The George and Dragon, and then a bit of a boogie at Castle Stonewall sort of thing. It was Stonewalls really in those days, yes, and that was a big night. That was kind of fun.

Oh, and end up at The Cast- – you know, if you really wanted a big night, end up at The Queen’s Arms because there would be a lock-in there, you know. I remember when The Queen’s Arms opened, it was like [laughs] we had a march from Stonewalls to The Queen’s Arms. Because they were both owned by Josie, weren’t they? [Laughs]. And we actually had the Gay Pride march and a great – you know, a banner and things, and it was literally just up the road. [Laughs] But they wouldn’t stop the roads for us.

Even though we had a police presence we had to walk on the path. And it was probably about 50 of us or so just walking up, and then we got there, and of course I think Cinders was working in the bar, and suddenly 50 people arrived all wanting a drink and thinking, “Yes.” It was a really small bar, and it took a bit of time to get served, you know.

Rosie: Yes, someone mentioned how you might spill out into the garden or the street and …

Richard: What, at The Queen’s Arms?

Rosie: At The Queen’s Arms, yes.

Richard: Yes, yes, yes.

Rosie: And there were chains and trip hazards and all sorts.

Richard: Yes.

Rosie: Do you have any memories of that?

Richard: Yes. Yes, there was that. I always remember the day after the Admiral Duncan bombing, yes of course everyone in Lewisham was worried about Cinders. And he was actually in The Queen’s Arms the next night, and he had a few bruises and cuts on him. And I remember chatting to him and he said, “Yes, I’m fine.” He was all right which was good, because the first person you think of in these – it’s a bit like with the Admiral Duncan thing, he was a bit – you know, he was the landlord there, so he probably was the one that was the last person to leave or something, so it was a bit worrying.

But yes, it was great to see him in there. I just remember him sitting outside having a fag and being quite cool about it, really, you know what I mean. Not too upset, you know what I mean. It’s like well that’s what it appeared to me anyway.

Rosie: One of the things that Paul has been interested in exploring with people, I mean from his own experience really, is how the communities were built around the pubs and how everyone would support each other in difficult times. Whether that was the Admiral Duncan situation, or obviously HIV/AIDS. Was that something that you felt was important?

Richard: Yes, when I first came to Lewisham I felt it. I was new to London, new to the gay scene as such, and the London gay scene, yes, it was … As I say, you had the Gay Men’s Drama Group and things like that, it was really useful. And going to Out Dance, or If, as it became, in The Albany was – it was a great club. [Laughs] There was these – I can’t remember his name. I can’t even remember, it’s like their names. Anyway, it was these three gay guys who would dance and almost – I think it was just pre-Vogue days, you know what I mean, but they knew all the Madonna dances.

And so they’d get up and do the Madonna dances. And Oscar who ran the club, you know, they’d get people dancing in a way, you know what I mean. They’d break the dance sides, and I know they – [laughs] And Oscar actually used to let them in free because they – but they took it incredibly seriously actually with the dancers. [Laughs]. You know, “Excuse me. Excuse me,” you know, and get to the bar. “We’re the dancers, we need a drink now, sorry.” [Laughs]. And it was just all really fun. Yes, it was a fun night out.

And yes, with HIV. I’m trying to think about HIV and AIDS though. Yes, there was obviously lots of – you know the Metro Centre in Greenwich was a big plus. And also The Positive Place in Deptford was set up. I don’t know how true this is, but what I heard which I think is quite interesting, is – because I heard it from somebody who was involved in setting up The Positive Place. And the reason it was set up was because The Lighthouse was so far away, you know, and you may as well go to Brighton or something. To get to West London would take an hour and a half, so to have somewhere local – and it was a great idea.

And they got funding from Greenwich, Southwark, Lewisham to help fund this thing because obviously people from all those boroughs would use it. But one borough wouldn’t give any funding because they didn’t have people with HIV and AIDS in it, and that was [laughs] Bromley. They would not. And this is how rumour had it anyway. And you do hear quite anti-gay things coming from Bromley, like when they tried to set up a gay pub there was a petition against it. And also about the Bromley Court Hotel, about how they wouldn’t have people – they wouldn’t do civil partnerships there even though they were licensed. And Bromley Council said, “Yes, that’s all right, you can do that,” even though technically they were lic- – you know, they got the license from the council, you know.

But yes, so I know friends who used – and, yes, I went there for a couple of social dos and things at The Positive Place, and it was a really useful space for people with HIV and AIDS. It was, yes, very, very useful. I think it’s when the Metro Centre started, was it, at The Positive Place? Maybe. Maybe, I’m not sure. I think they were involved in it anyway.

Rosie: Can you shed on why and when the various bars and pubs closed?

Richard: Why and when, hmm. Oh, well, yes, there were ones that just lasted overnight. There were fly by night pubs that were gay, as particularly as pubs generally closed, you know what I mean. They still are, aren’t they, you know what I mean, but sometimes a pub in its last dying days, if you like, would have a gay night just to see – to get people in, you know. But the main pubs, obviously The George and Dragon is still going strong. Yay. But The Phoenix shut about – I think about 10 years ago with all that new development in Lewisham, you know, all the new – well, it was all part of that I think.

And Stonewall’s probably – no, Stonewall’s – I think the last time I went to Stonewalls was actually [laughs] around the Olympic time, 2012, and they did a breakfast. Because a friend of mine, he actually managed to hold the torch. They had a relay race to – you know, the Olympic torch came through Lewisham, and he did it for his charity. And so we all went and supported him, and then Stonewall said they would – or I think it was 286 then – do a breakfast. [Laughs] It was tinned mushrooms. [Laughs] I’m sorry. I’m sorry, but [laughs] yes, you know, [laughs] it’s like – yes. Yes, I can’t eat them. I’ve never eaten tinned mushrooms since. I don’t think I – you know what it’s like. It’s not something you can – you know, they’re not –

Rosie: It’s something that shouldn’t even be tried.

Richard: Yes, exactly. [Laughs] Yes. Exactly, yes, yes. And they tried, do you know what I mean, but I think that was one of the last times I went there. Yes, that was early, sort of 10 o’clock in the morning having breakfast. So they tried to put it on, you know.

Rosie: Yes, so did you get the sense that it was on its last legs as a venue?