Professor Wen-Chin Ouyang reflects on the crisis of the humanities and how they are necessary to our lives

London. Sunday. 24 October 2021. Morning. For the first time in years I open my eyes to sunshine filtering through the bedroom curtains. I grabbed my mobile. 9:16 am. I am 16 minutes late calling my mother in Taipei. There have been earthquakes here, my mother says as soon as she picks up the phone, of magnitude 6.5 on the Richter scale. I turn to The Guardian on my iPad and look for more details. My heart sinks as I read ‘New university job cuts fuel rising outrage on campuses’. Goldsmiths has announced 52 compulsory redundancies among professional staff and academics, the latter all in English and the humanities. I heard about the job cuts from friends at Goldsmiths’ Centre for Comparative Literature but reading about them in The Guardian I am glad in a perverse way that the crisis at Goldsmith has made national news. Perhaps it is time for us to stare the crisis in languages and humanities in the eye. SOAS recently went through a similar experience. Despite the rigour of our research and the recognition of the importance of languages and humanities in our daily life, funding cuts and low recruitment in many of our academic programmes, exacerbated further by the Covid-19 pandemic in the past two years, have led to massive job cuts accompanied by curriculum reform. Many languages have disappeared or are disappearing from school and university curricula and literature offerings are greatly diminished. Looking at the Arabic Programme(s) at SOAS from the prism of what I knew when I first moved to London in 1997, I see ruins of what once was. The MA Arabic Literature was withdrawn together with most of the advanced BA and MA literature modules. Our language modules are reduced in intensity. It is becoming increasing difficult to graduate students with high levels of language proficiency, cultural literacy, and literary skills, just as the world needs them even more than ever. I am reminded of the opening lines of a long qasida poem (translated by Suzanne Stetkevych) by Labid, a sixth century Arab poet, who stood before the campsite of his departed beloved and lamented:

Effaced are the abodes,

brief encampments and long-settled ones;

At Mina the wilderness has claimed

Mount Ghaul and Mount Rijam.

Then I stopped and questioned them,

but how do we question

Mute immortals whose speech

is indistinct.

Stripped bare where once a folk had dwelled,

then one morn departed;

Abandoned lay the trench that ran around the tent,

The thumam grass that plugged their holes.

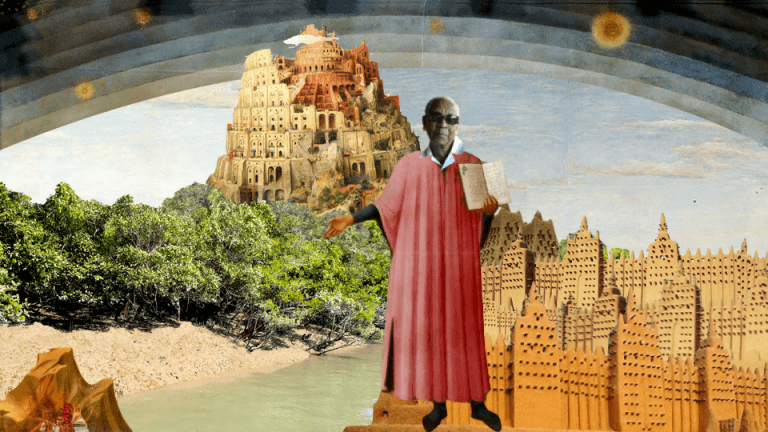

But I do not wish to lapse into melancholy. Rather, I want to dare to hope against hope, to will a rebuilding from the abandoned dwellings starting from left behind traces, for the Covid-19 pandemic has paradoxically shown us how instrumental languages and humanities are in the ways individuals and communities are responding to the challenges posed by the new coronavirus. A team of SOAS colleagues have been gathering information about the ways in which different linguistic communities in London are responding to Covid-19. Their work on “cultural translation and interpreting of Covid-19 risks” is a UKRI/AHRC Covid-19 research project. From the statistics published to-date, we can see that multilingualism is at work in how migrant communities access information. Most migrant communities access information outside the UK and in languages other than English. And the information they read comes from “formal” news channels (the BBC and the recognized news papers) as well as social media, tabloids, and “collective wisdom” inherited from a history of managing pandemics going around in their global communities through, let us say, chats on their mobile phones. Just as the new coronavirus has connected the “fate” of the entire globe, multilingualism and technology have also brought the globe into one “destiny.” We are struggling together to contain the spread of Covid-19 and at the same time to work out our individual and collective code of conduct under the circumstances of global entanglement.

This has been that space where similar issues have been raised, interrogated and “translated” into everyday conduct. Ibn Butlan, a Christian physician from Baghdad, who left behind a work on medicine and another on his travels in the Middle East, chose to write in the adab tradition pioneered by Ibn al-Muqaffa‘, and in a literary form, the classical Arabic maqama, about the attitudes of the physicians towards illness, and particularly the plague of 1154-55, and their patients, and more importantly “truth” about the plague. Ibn Butlan does not deign to tell us what “truth” is, but by dramatizing the politics of “truth,” the details that go into each version, and the cost of these in actual lives lost (to the plague), he makes visible and tangible the consequences of each thought and each action on individuals and their community. This is the role the humanities have always played, and can still play, if we adjust our academic approach to them.

As early as 2008, Rita Felski examined in Uses of Literature the paradox pervasive in academic study of literature. Critics justify the importance of their work by focusing on the “uniqueness” of the literary work, and by doing so privileging “distinctiveness,” “difference” and “otherness.” For, in the view of many, “the otherness of literature” is precisely “the source of its radical transformative potential”. However, “separating literature from everything around it, critics fumble to explain how works of art arise from and move back into the social world.” Felski goes on to say, “highlighting literature’s uniqueness, they overlook the equally salient realities of its own connectedness.” By calling her book “uses of literature” she proposes pluralizing reading practices, to include the familiar political and ideological and at the same time to go beyond these “to engage with the worldly.” The four part process of textual engagement she delineates, “recognition,” “enchantment,” “knowledge” and “shock” brings literature back to “configurations of social knowledge.” And this “social knowledge” tailored for the Covid-19 situation is what we need now and what world literature and the global humanities can offer.

My thoughts return to Goldsmiths and my mother in Taipei. I will be going to Taipei for the 2022 ACLA annual meeting. Being in my mother’s time zone will alleviate my anxiety about staying in touch with her, but taking part in a comparative literature conference will not, I am sure, calm my fears about the future of languages and the humanities. But we must find a way to show our funders and students the importance of languages and the humanities. That instead of cutting we should be strengthening, expanding and proliferating our offerings in these. For what needs working out is not just decisions about vaccination but also details of our everyday living.

Wen-chin Ouyang, FBA, is Professor of Arabic and Comparative Literature at SOAS, University of London. Born in Taiwan and raised in Libya, she has a BA in Arabic from Tripoli University and a PhD in Middle Eastern Studies from Columbia University.