Hanan Jasim Khammas, Visiting Doctoral Scholar at the CCL, reviews Fethi Benslama’s Psychoanalysis and the challenge of Islam (trans. by Robert Bononno. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. 272 pp. ISBN 978-0816648894)

Fethi Benslama is a French-Tunisian psychoanalyst, a Parisian academic, and the author of several pieces on political Islam. His seminal work Psychoanalysis and the Challenge of Islam (2002) was translated into Arabic by the author’s sister, the Tunisian scholar and feminist critic Rajaʾ Benslama, who is also interested in the psychoanalytic deconstruction of gender and sexuality in Arab and Muslim cultural heritage. Both authors are a must-read, given the poor attention psychoanalytic circles have given to the questions of Islam and its historical development.

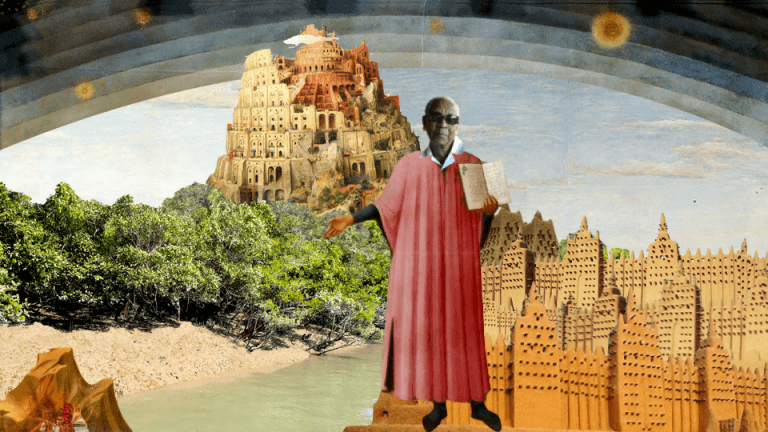

In Psychoanalysis and the Challenge of Islam, Benslama addresses mythical, theological, and literary textual accounts if the Islamic genesis to provide an explanation of what he calls the crisis of Islamic radical fundamentalism. The later Un furieux désir de sacrifice. Le surmusulman, published in 2016, seems to provide a clearer and easier reading to the subject; nevertheless, the earlier volume already offers an insightful body of analysis to address many of the big questions of Islam. Reviewers have claimed that the outstanding originality of this work lies in the author’s observation that the Islamist discourse is “tormented” by the question of origin, and that Islam, unlike the Judaeo-Christian tradition which symbolised God as father figure, “denies”, as Benslama put it in an interview with Gabriela Keller (“Islam and Psychoanalysis: A Tale of Mutual Ignorance”, June 13, 2006), “any connection between God and a father figure”. In fact, “God is far removed from humanity because he may not be compared in any way with the idea of mankind” which makes for an “abstract religion” and “abstract God”. This observation is substantiated in the book in a thorough comparative analysis of the history of monotheism, between the Judeo-Christian tradition and Islam. This leads to what I believe is the book’s strongest claim, the explanation of the origins of violence against women in that “the ‘torment’ of origin manifests itself in Islam in the suppression of the feminine, which combined with the absence of the divine paternal, accounts for Islam’s extreme masculine monotheism and political extremism” (as Mahdi Tourage puts it in his 2012 review of Benslama’s book for Contemporary Islam (6): 201-203). Benslama reaches this conclusion through the analysis of the role played by Khadija – the prophet’s wife; and Hagar – mother of Ishmael, Abraham’s son, the progenitor of Arabs. According to his analysis, both Khadija and Hagar represent feared figures for having access to knowledge about what cannot be known, and what is impossible to have access to – God. Hagar could see and hear God (81-83), and Khadija confirmed Mohammad’s prophecy even before he knew he was a prophet. When visited by the Archangel Gabriel, Khadija lifted her veil to show the prophet that if the angel leaves, then he is a divine angel sent by God, if he stays, then he is an evil demon. For Benslama, both stories show that women seem “possessed of a ‘negativity’ that can be used to prove the truth of the Other. The veil separates truth from its negation”; and that “[m]an is inhabited by the Other but does not recognize it. Without the woman’s unveiling, and therefore without the veil, he would have remained indecisive, living but doubting god” (135). Thus, the necessity for the veil and the suppression of the feminine come from not the demeaning attitudes towards women, but rather from an existential demand governed by fear.

As refreshing and enlightening as this may sound, one cannot but wonder how Islamic feminism responds to this, for such analysis posits both the exegesis and women-scholar’s reading of the Qurʾān into a questioning examination, or as put forward by Slavoj Zizek in “The Power of Woman and the Truth of Islam” (ABC, May 19th, 2012): “One thus cannot simply oppose the ‘good’ Islam (reverence of women) and the ‘bad’ Islam (veiled oppressed women). And the point is not simply to return to the ‘repressed feminist origins’ of Islam, to renovate Islam in its feminist aspect: these oppressed origins are simultaneously the very origins of the oppression of women. Oppression does not just oppress the origins; oppression has to oppress its own origins”.

In addition, even though the genesis of Islam had excluded God from the symbolic order, maintaining Him in the domain of the un-symbolised – the real –, the analysis does not address the fact that Islamist fundamentalism thrives on the promise of the reunion with the creator and an eternity of living under his blessing in heavens. What is the significance of this ultimate fantasy in the articulation of desire? Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, the analysis also ignores the role of orientalist misrepresentation in the formation of radical fundamentalism. Throughout history, the orientalist imagination and its enacting institutions have created images of Islam and Muslims which have also intervened in the reconfiguration of the subject’s interconnected triad of registers: imaginary, symbolic and the real. Let us recall the Syrian thinker Ṣādiq Jalāl al-ʿaẓm, who argued in “Orientalism and Orientalism in Reverse” (1980, reproduced in in Orientalism: A Reader, ed. by A. L. Macfie, EUP, 2000; also available at https://eutopiainstitute.org/2021/05/orientalism-and-orientalism-in-reverse-sadik-jalal-al-azm/) that Ontological Orientalism – “the foundation of the image created by modern Europe of the Orient” – had “left its profound imprint on the Orient’s modern and contemporary consciousness of itself” (pp. 230-231). How does the image created by Ontological Orientalism participate or intervene in the construction of the Islamic fundamentalist psyche, which al-ʿaẓm described as Reversed Orientalism?

The radical investigation that this work presents connects different complex areas, some of which are left untouched, but this can only mean that Benslama has opened for us a path full of questions which comparative literature can definitely bring answers to.

Hanan Jasim Khassam is completing her Doctoral research at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona on the representation of the body in contemporary Iraqi fiction. As part of her residency at the CCL, Hanan has organised the short seminar series Remnants of the Iraq Wars: Iraqi Literature Twenty Years after 9/11; she chaired the first event, Iraq: Corporeality & Memory. Iraqi literature, 20 years after 9/11 (7 September 2021) and discussed her research in the second, Aftermath Bodies: Corporeality in Contemporary Iraqi Fiction (22 September 2021). Video recordings of both are available on the events’ page. This is Hanan’s second blog post, written as part of her visit at the CCL – the first one was on The Banality of Violence: Art and the narrative of victimisation.