Barbara Goff and Michael Simpson kindly offer an account of and some reflection on the paper they gave at the CCL on 2 February 2023 (which was not recorded).

At the Research Centre for Comparative Literature on 2nd February 2023, we had the honour, and pleasure, of presenting a joint paper, under the title ‘Votes for Medea: the British women’s suffrage movement and the classical franchise’. This paper found its place in the thriving series of events titled ‘Sing in me, Muse: the Classical, the Critical, and the Creative’. Our paper was a happily opportune means for us to introduce to our responsive audience at the Centre work in progress on a major research project currently advanced in some ways and still in formation in others: this presentation unfolded not only the classical dimension behind and around the campaign to secure the vote for women in Britain but also an outline of the larger project of which our findings about this campaign form an important part. Another part of our project, concerning the classically orientated historical novels of the feminist writer Naomi Mitchison, will be presented to the Classics Department at Yale University in April 2023. Before adverting briefly to this large project and then elaborating on this detailed case study from it, we shall say just a little about the methodology enabling this project, and about how that methodology may be related to Comparative Literary Studies.

Informing our project is the relatively new discipline of Classical Reception Studies, as distinct from the more established mode of inquiry associated with ‘the Classical Tradition’. We say ‘discipline’ here, with reason, though we could provide a better sense of the scope and potential of this organised array of concepts and tools and the associated body of developing knowledge by thinking of it as a sub-discipline within, inter alia, Classical Studies itself, cultural history, the history of science, and, of course, Comparative Literary Studies. At Goldsmiths, Classical Reception Studies, as it emerged swiftly onto the larger intellectual landscape, certainly found a supportive home in what used to be the Department of English and Comparative Literature; and it prospers now under the aegis of the booming, zooming Research Centre for Comparative Literature. Classical Reception Studies is, in a now fairly standard definition, the inquiry into how and why the ancient cultures, works, texts and images of Greece and Rome have been, and are still, re-deployed in later times and often other places, by different cultures, to address various needs and purposes. This mode of inquiry places methodological emphasis on the ‘pulling power’ of such later ‘receptions’, and less on the ‘pushing power’ of the ancient sources themselves; following from this distribution of emphasis, this method of inquiry also allows for comparisons to be made between and among such later receptions. Thus, the affinity with Comparative Literature, both as creative practice and critical inquiry, is clear. Beyond this ready concinnity, Classical Reception Studies may also bring to the comparative table a greater historical depth, in the concern with ancient works, and a reinforced focus on the how and the why of later intertextual citations, on what might motivate classical references as well as how they are latterly inflected or distorted.

We turn, briefly, to the topic of our large project. Provisionally titled ‘Working Classics: Greece, Rome, and Cultural Hinterlands of the British Labour Movement’, this project is designed as a selective cultural history of certain moments of political history, concerned with reform, more or less radical, from about 1900 to the mid-1970s. In pursuing this project, we are building on the ground-breaking work of Edith Hall and Henry Stead’s A People’s History of Classics: Class and Greco-Roman Antiquity in Britain and Ireland 1689 to 1939, as well as their Greek and Roman Classics in the British Struggle for Social Reform. This history is vast, hence our contained span and designed concentration on certain pivotal moments. The starting point of 1900 is thematically as well as numerically neat, since it is the date of the foundation of the British Labour Party which was closely followed, in 1903, by the establishing of the Workers’ Educational Association, the WEA. Though these institutions were independent of one another, the Labour Party sought to represent, and so enfranchise politically, the new, industrial working class, while the WEA developed locally-based programmes of adult education aimed at enfranchising that social constituency culturally. In the main, our selective cultural history will be focussed on institutions, while movements, generations, groups and individuals will come into focus as forces and agents that crucially forge, form or flank those institutions, political, cultural and educational.

Across a range of institutions and cultural terrain, our inquiry has yielded, or confirmed, at least four broadly consistent conclusions: first, cultural self-enfranchisement, in respect of the Greco-Roman classics, is regularly a precondition of political enfranchisement, in different forms; secondly, underlying these related modes of enfranchisement is a surprising collective sense of cultural entitlement as well as of more familiar political ambition, whereby those not structurally placed to receive classical culture or education insist on obtaining a share of it, without being intimidated by it, and then often turn it to their own larger, generative ends, whether as groups or individuals. Thirdly, these goals often exceed merely better access to the classical sources themselves, as well as expanding the terms and resources inherent within them; these classical sources, while regarded as eminently valuable, are made subservient, as means, towards ends that are often defined by the culturally disadvantaged or deprived, as they make classical culture intrinsically and instrumentally their own. In doing so, furthermore, these inquiring spirits may well change, perhaps creatively, that very classical culture and education. That is our fourth conclusion. Such a process of change is nourished by a variegated stream of cultural traditions coursing vigorously from the nineteenth century and centred on an elevated social mission for education: ranging from efforts by middle-class writers, often classically equipped, to adapt a liberal education to new possibilities of mass education, on one side, to the more working-class Mechanics’ Institutes and the WEA, on the other, there is a powerful conjunction between cultural dissemination and radical social reform, conspicuous in the women’s suffrage campaign particularly and the Labour Movement generally. This inheritance, of course, is living history. Like most, the two of us are beneficiaries, before becoming students, of these historical advances; as particular illustration, Simpson attended a state secondary school which did not offer classical languages; his study of Latin began via a correspondence course which was paid for largely by his local Mechanics’ Institute, one of the great enfranchising institutions from nineteenth-century Britain.

We turn now to our case study. To research the presence of classical material in the suffrage movement, we trawled the major suffrage journals. We read Votes for Women, published by the Women’s Social and Political Union, The Common Cause, published by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and a number of pamphlets that the British Library houses. It became clear that classical material was not a major presence in the suffrage publications, which were often devoted to blow-by-blow accounts of campaigns, Parliamentary manoeuvres, and news about the many and varied disadvantages faced by women of all classes and occupations, owing to their exclusion from the franchise.

But it was equally clear that classical material had a substantial grip on other parts of the journals: there are articles about ancient warrior women such as the Amazons, book reviews of studies of ancient matriarchy, notices of performances of Greek tragedies newly translated by Gilbert Murray, repeated references to the women guardians in Plato, and passing references to the matrons of ancient Rome, alternately noble and terrifying. Reference to the classical material is more sparse than to, for instance, the Bible or Shakespeare, but antiquity is made useful by providing either a long perspective on women’s powers or conversely the long history of injustice. The references to antiquity are usually short and not very detailed, but they don’t simply assume an educated acquaintance with classics; rather, they want to equip readers with useful arguments and examples. In these ways classical antiquity offers authoritative models for contemporary women, so the authority of antiquity is not hereby undermined, but repurposed; yet we might also reflect that the very fact of women writers’ deployment of antiquity speaks volumes about women’s contemporary participation in culture and community.

We had to be selective for our paper at the Centre for Comparative Literature, and so we focussed on the several appearances in the journals of Euripides’ tragedy Medea. Greek tragedies were made newly available in the early twentieth century to a more general audience by the translations of Gilbert Murray, himself a supporter of women’s suffrage, as well as a leading educator.

In the Greek drama, Medea has rescued her lover Jason from various perils, using magic and murder, and has come with him away from her homeland to Greece, where they have married. Subsequently, Jason desires a safer, less controversial connection, and is about to marry the local princess instead. Medea’s revenge is notorious: she engineers the death of the princess and her father, and then stabs both her sons, leaving Jason to lament the end of his family and prospects.

How is Medea employed by the suffrage journals? Two examples can show the range and force of reference.

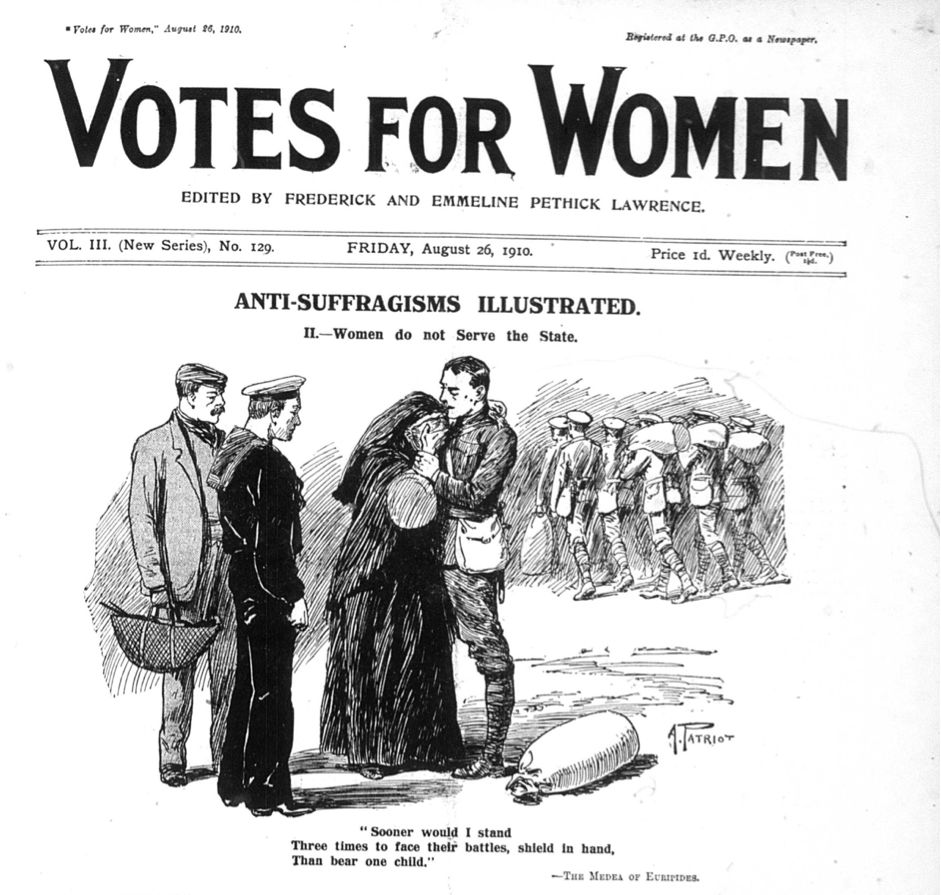

One important point is that Medea never appears in the journals as an infanticide. Oblique references may be made to the events that overtook her family, but there is no explicit acknowledgement of her notoriety. Instead, the suffrage journals often work with a particular famous speech from the play. Addressing the chorus of sympathetic women in Corinth, Medea laments women’s lot, and sums up its injustice in the remarkable claim that she would rather go into battle three times than endure childbirth once. The suffrage publications quote this speech in the context of what was known as the argument from physical force. This anti-suffrage argument held that women were logically excluded from the franchise because they were incapable of going to war and defending their country. Suffrage activists countered this argument by pointing out that not only did history show that women did fight, but more to the point, they regularly risked their lives in producing children for the country. A cover image for the journal Votes for Women in 1910 quotes Medea’s speech and illustrates it.

The quotation reads, from Murray’s translation:

Sooner would I stand

Three times to face their battles, shield in hand,

Than bear one child.

If we interpret the image correctly, it is the woman weeping because she will lose her children in war, and the quotation reflects ironically on the comparative worth of ‘male’ and ‘female’ contributions to life and death.

A second speech in Medea, by the chorus, laments that men have been in charge of poetry and song, and women have not been able to correct the historical record by speaking for themselves. They say that now (Goff’s translation)

Speech will change to hold my life in good repute.

Honour will come to the female race;

The muses of old singers will cease to hymn

my faithlessness.

In 1911 Votes for Women publishes a speech by the actor and writer Elizabeth Robins, given at the Women Writers’ Suffrage League Meeting, in which she claims that the vision in Medea is now coming to pass. Robins speaks of women writers who are going to change the representation of women, and thus to fulfil at last the lines in Euripides’ play about a day when the old stories will change. The play is thus useful to an audience specifically of writers, since it offers an account not just of women’s wrongs, or rights, but of representation. The authority of the classics is transformed out of history into prophecy, instantiating and explaining, at a stroke, how the ancient Greeks might be relevant and useful to the contemporary suffragists.

Although the references to classical antiquity do not dominate the discourse of the suffrage publications, they are varied, lively and memorable, and are readily turned to the goal of the franchise.

In the wake of International Women’s Day, we are pleased to offer this blogpost. We thank Lucia and Isobel for our invitation to speak and for the necessary arrangements, and we are grateful to our animated audience on the night, who engaged with our arguments and material and posed questions that are helping us with next steps.

Barbara Goff is Professor of Classics at the University of Reading. Dr. Michael Simpson is Distinguished Visiting Research Fellow at the CCL.