Rebecca Chamberlain’s research sets out to understand how and why individuals create and respond so powerfully to works of art. Rebecca studied for a foundation degree in Art and Design at the University of the Arts, London before moving into cognitive science. She completed her undergraduate and postgraduate studies in Experimental Psychology at University College London researching the psychology and neuroscience of representational drawing ability, before joining Professor Johan Wagemans’ lab at KU Leuven in Belgium as a postdoctoral researcher in 2013. Rebecca joined Goldsmiths as a lecturer in 2017.

Rebecca Chamberlain’s research sets out to understand how and why individuals create and respond so powerfully to works of art. Rebecca studied for a foundation degree in Art and Design at the University of the Arts, London before moving into cognitive science. She completed her undergraduate and postgraduate studies in Experimental Psychology at University College London researching the psychology and neuroscience of representational drawing ability, before joining Professor Johan Wagemans’ lab at KU Leuven in Belgium as a postdoctoral researcher in 2013. Rebecca joined Goldsmiths as a lecturer in 2017.

During a retrospective of Pierre Bonnard at the Tate Modern last year, I was invited to give a tour of the exhibition. I was to take a psychologist’s eye to Bonnard’s work and explore the phenomenon of slow looking. With research showing that visitors to galleries spend on average just 27 seconds in front of an artwork, slow looking is a response to our increasingly hectic approach to art, and just about everything else. Matthew Gale, the curator of the exhibition, remarked that Bonnard’s paintings ‘really reward very close and extended scrutiny’, a perfect candidate for the slow look. This remark could be true of many paintings in the Tate’s collection, so I set out to investigate why Bonnard’s work in particular invites the viewer to slow down and immerse themselves in his work. In doing so, I discovered three painterly techniques that Bonnard used that produce visual effects that confuse our visual system at first but ultimately reward us if we take a bit more time to look.

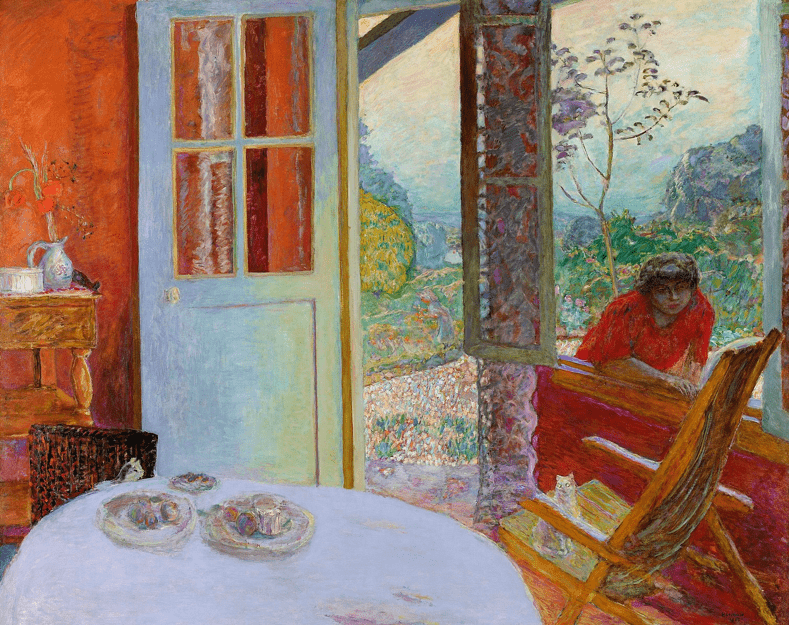

First, Bonnard used colour in unusual ways. He often applied the technique of simultaneous colour contrast, which involves pitching opposing colours against one another. You can see this in the blue door against the orange wall in ‘Salle à manger dans le jardin’ (Figure 1). At the same time, Bonnard also used equiluminant hues to make boundaries between parts of his paintings appear to move around. Equiluminant hues have a high colour contrast while at the same time having a low contrast in brightness. The processing of colour in the brain is divided between visual pathways responsible for brightness and hue, with the hue pathway being relatively poorer at processing the position of things in space. Part of a painting that is equiluminant with the region next to it will be hard for our brain to locate accurately, accounting for this strange visual effect.

Figure 1. Pierre Bonnard, Salle à manger dans le jardin (Dining room in the garden), oil on canvas, 164 x 206 cm, 1934-5. Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Second, Bonnard distorts space by rejecting out traditional approaches to perspective, and instead painting wide-angle views using a patchwork of viewpoints. An example of a very wide-angled view can be seen in ‘Salle à manger dans le jardin’ again, yet to the viewer this scene may not look odd, because the full width of our vision is up to 180 degrees. In fact research has shown that viewers prefer painterly depictions of visual space in comparison to other geometrically accurate representations. Bonnard is able to incorporate a very large amount of spatial information into a relatively small space on the canvas, inviting the viewer to explore the painting and feel immersed in the wide-angled view.

Finally, Bonnard plays with ambiguous and hidden figures. Bonnard must have noticed that our subjective experience of a visual world made up of objects, clearly separated from backgrounds, is an illusion. He plays on this illusion by often making it difficult for the viewer to separate figure from ground in his paintings, using techniques like equiluminance. Figure-ground segregation is one of the key roles of the visual system, and a problem that Gestalt psychologists have been investigating since the 19th Century. When the normal process of figure-ground segregation gets disrupted we often may think we see a figure where there is none (a phenomenon called paraeidolia) or we may struggle to resolve the scene at all. Creating ambiguities in artworks encourages the viewer to look longer, and creates a more intense aesthetic response.

It does seem that Bonnard’s work rewards intense scrutiny; it is unlikely that we will be able to unravel the puzzles hidden in the artworks if we only spend a few seconds glancing at them. However slow looking can be challenging (and even frustrating) if you haven’t done it before, so how do we get better at it? Some clues lie in research conducted on the way artists look. When artists look at paintings they cover a greater area of the painting, and look at the relationships between different parts of the painting, a more ‘global’ way of looking. This way of looking at art is unlikely to be hardwired from birth, it is more likely to be developed through years of looking at the world with intense scrutiny. So in this time of lockdown, perhaps try out slow looking for yourself. A recent exhibition at the Manchester Art Gallery called ‘And Breathe’, invited visitors to spend more time with a few selected artworks, with guidance on how to look slowly. You can access the list of artworks and audio guides with mindfulness meditation here.