Tug of war on the Goldsmiths’ College back field in 1961 for Rag Day. ‘it wont rain roses’ editor and author David Elliott is in the woolly jumper centre and looking backwards. But the pamphlet was looking forwards to building a better education system.

A common theme of the history of Goldsmiths is the recurrence of students and staff politically campaigning to make the world a better place.

It’s possible to select any decade of the 20th century and find evidence of lobbying and what could be described as political activism, or ‘political education.’

It does not mean all or even most of the students and staff were involved at any one time.

Or indeed that there was necessarily consensus and agreement.

Award winning and leading UK publisher, David Elliott, was an undergraduate student between 1961 and 1964 and he believes there was a ‘progressive atmosphere’ and ‘radical spirit’ at the college when he was there.

The then Warden of the College, Ross Chesterman, later knighted for services to higher education, had a reputation for being tolerant of protest and student activism while at the same time encouraging constructive and reasoned debate.

This may account for Goldsmiths’ College winning the University of London debating cup two times in the early 1960s and David Elliott was in one of victorious teams knocking the big London Colleges off their perch.

Around thirty years earlier in 1932, a delegation of students had marched on Parliament and lobbied their MPs against massive cuts in funding for schools and teachers. The school leaving age then was only 14.

This was a time when no more than 12 per cent of children received a secondary education and half of those had to pay for it.

When one of the Goldsmiths’ students asked an MP why so much more money was being spent on arms instead of educating the poor he was accused of being a Bolshevik and directed to go and stand on the other side of the lobby hall as though he had been a naughty boy deserving of detention.

In 1962 a later post Second World War generation of Goldsmiths students were taking their message to Parliament again to continue the struggle- this time to raise the school-leaving age to 16, achieve more participation in higher education and expand equality of opportunity.

The Goldsmiths’ student union newspaper Smith News, which sold weekly for three old pence, reported on June 1st 1962 that in a grand lobby of Parliament over 50 MPs had been briefed by a delegation of 450 students.

David Elliott recalls: ‘the mass picket on Westminster was organised as almost a military operation with hired buses shuttling students every hour to the House of Commons- with Marshals and stewards controlling the flow. I wore an armband with CHIEF STEWARD which, alas, got lost.’

The paper was asking the questions ‘What did we achieve?’ and ‘Where do we go from here?

It acknowledged: ‘We have given a lead to other Training Colleges, and already seven colleges have sent petitions to the Ministry. Others are asking our advice; letters from Goldsmiths’ students are appearing in local newspapers, questions are to be asked in the Commons, and MPs are busy writing replies or fixing appointments.’

Many students and staff were committed to a national ‘Campaign for Education’ which drew support from all the political parties.

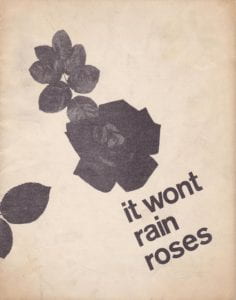

In 1963 one of the major contributions of the Goldsmiths dimension was a research pamphlet titled: ‘it wont rain roses.’ The lack of an apostrophe in ‘wont’ was a deliberate design and campaigning decision.

David Elliott remembers that students and Smith News ‘mostly contributed sections and my job was to curate and edit the pamphlet as it developed. I ended up writing most of it.’

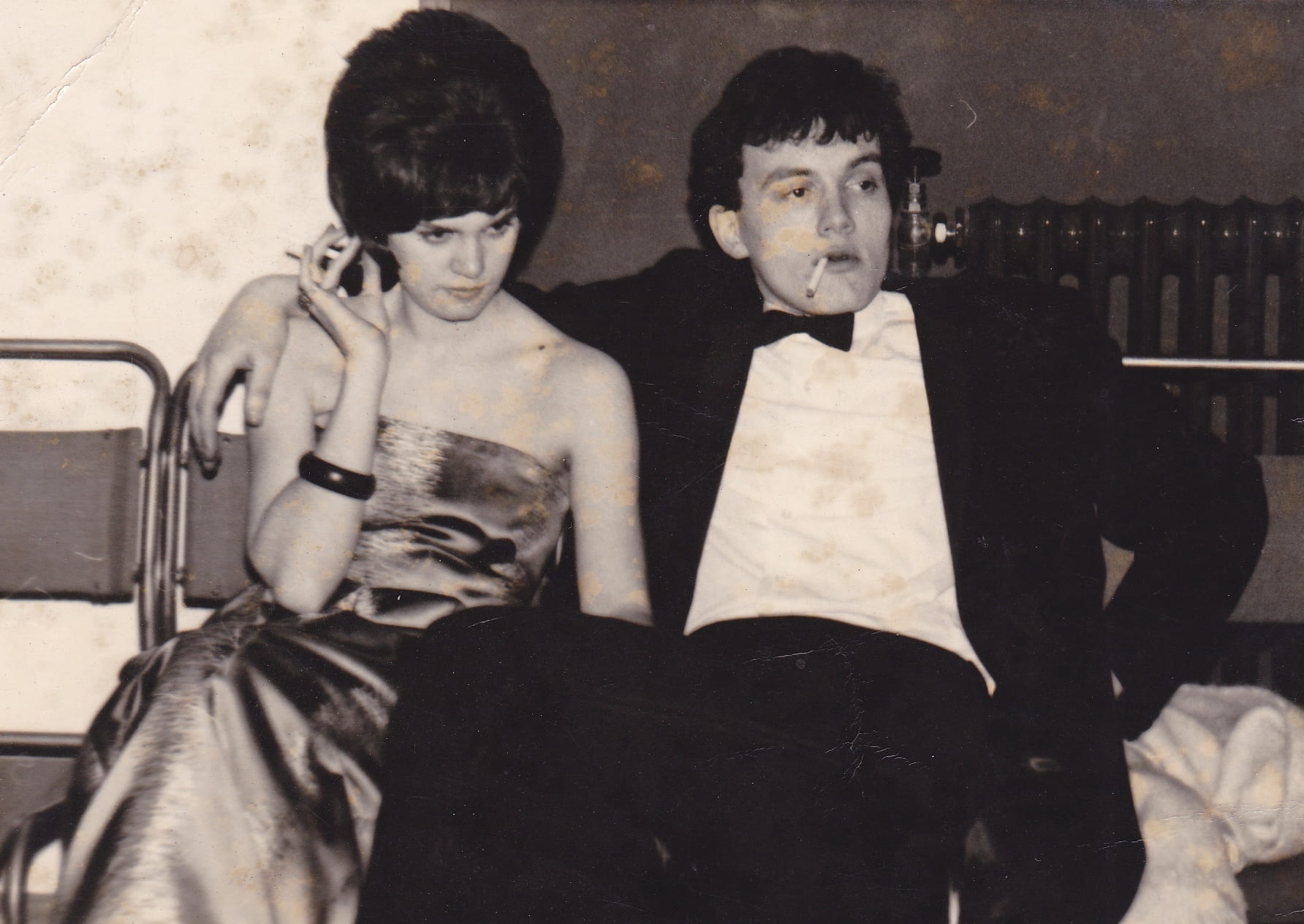

David Elliott, pamphlet editor, writer and undergraduate on the right. ‘It was a Goldsmiths/University of London ball event as Barbara Spencer (my ‘date’) was women’s Vice-President so I had to hire a Dinner Jacket and borrow a bow tie. It was in the Great Hall and I was in my second year in 1962.’

He was given ‘amazing support’ from an education lecturer, Charity James, who was ‘in effect the main copy editor and supplied the title. We printed 1,000 copies I think, which the National Union of Teachers distributed. All I can remember was it was quoted in Parliament and The Times called it ‘shrill but necessary.’

David has held onto one of the few surviving copies.

Only Warwick University’s library appears to have a copy available for researchers.

The title ‘it wont rain roses’ was inspired by the George Elliot quotation: ‘It will never rain roses: when we want to have more roses, we must plant more roses.’

The original cover of ‘it won’t rain roses’ ‘A booklet written and published by Goldsmiths’ College, Campaign for Education.’

Charity James would become a legend in education. She would be a founder and Director of the Goldsmiths’ ‘Curriculum Laboratory’ and authored the seminal publication in 1968 ‘Young Lives at Stake: A Reappraisal of Secondary Schools’.

In his 1996 memoir ‘Golden Sunrise: The Story of Goldsmiths’ College 1953-1974′ Sir Ross Chesterman wrote: ‘There were, on the staff of the College, many really distinguished people, some with original ideas and the enthusiasm and energy to bring them to action and fruition. Mrs Charity James was a very good example of what I mean […] She had a group of some twenty comprehensive Heads and senior teachers seconded to work on her course. Her vigour, her imagination and her confidence quite won the hearts of the London Heads and their staffs and, as I could see, literally made them new people […] The Curriculum Laboratory greatly increased its impact and its influence by regularly producing a publication called Ideas, published by the College.’

“it wont rain roses’ began by saying that the pamphlet was committed:

‘…it is written by people who are intimately concerned with education in this country, by people who are training to become teachers. In a year’s time most of us will be dealing with children – perhaps your children. We shall be attempting to give them an education. Therefore we are committed. We believe that the education many children receive today is shoddy and a disgrace; an insult to the word Education. And this we hope to show you in the pamphlet.

Its theme is a simple one. At the present time Education is not being given the priority that it deserves. In 1963 more money is spent on Advertising and expense accounts than on Education.

The Government is not prepared to provide enough money for expansion and development; the teachers do not possess a professional attitude to their role in Society; and many parents tend to regard the Eleven Plus as the be all and end all of the system. [The Eleven Plus was an exam children took at primary school when 11 years old. A minority would be selected for grammar schools with many remaining in secondary education until 18 when they would take A’levels and were encouraged to go to university. The majority would go to what were generally regarded as less academic secondary and technical schools with most leaving school at 15.]

We live in an age of great industrial wealth, yet 55% of Primary Schools still in use today were built in an age of gaslight. If this is the legacy offered to so many young children today then we believe that something is drastically wrong.’

Front cover of the weekly student newspaper ‘Smith News’. David Elliott writes: ‘The three students in the photo are (left to right) Malcolm Laycock (Goldsmiths’ Student Union President) John Harvey, Editor of Smith News, and a first year student I believe was called Chris Prior. The photograph was taken outside the St Stephen’s Hall entrance to the Palace of Westminster. The caption is a ‘joke’ which you might have gotten- it was an advertising slogan for a tablet which dealt with bad breath and used with images of people up close…’ John Harvey would go on to become a leading award winning scriptwriter and crime novelist. Malcolm Laycock became an award-winning national broadcaster for the BBC.

In its concluding section the pamphlet said:

‘Education is not a luxury that only rich countries can afford. It is a vital necessity. Because of our persistent apathy, thousands of young minds are being wasted, and we risk national decline. Our suicidal values must change. It is not a question of can we afford it. It is a question of can we afford not to do it. And the answer is that we cannot.’

It can certainly be argued that Parliament did, eventually, answer the call in ‘it wont rain roses.’

By the late 1960s there was massive public investment in education.

University education expanded exponentially.

Comprehensive education was introduced and most grammar schools phased out.

The Eleven Plus examination was officially abolished, though many local education authorities continued to organise similar examination and testing at eleven which resulted in secondary school selection.

David’s generation of student teachers undoubtedly made a contribution to the national Education debate.

And although he and his fellow campaigning activists were a minority of the students at Goldsmiths, it can certainly be argued that their impact and contribution have been memorable and significant.

A photograph taken by David Elliott of Christmas Dinner at Aberdeen Hall in 1961. The Hall of Residence no longer exists. Goldsmiths’ College students usually spent their first year in one of a number of Halls of Residence scattered around South East London and Kent. In the second and third year, students became known as ‘Homers and Diggers’ meaning they either lived at home or in rented ‘Digs’.

Find out about Goldsmiths’ College student culture in the late 1960s by visiting the Golddream Exhibition in the Kingsway corridor of the Richard Hoggart Building 4th March to 14th April 2019.

For more on the history of Goldsmiths sign up for Professor Tim Crook’s inaugural lecture Monday 11th March 2019 6 p.m. Ian Gulland Lecture Theatre, Goldsmiths, University of London.

That’s So Goldsmiths– a forthcoming history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.