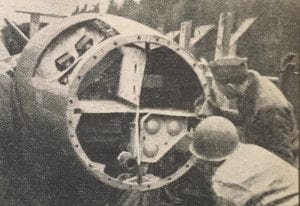

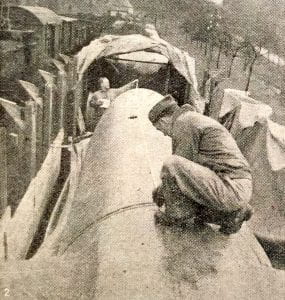

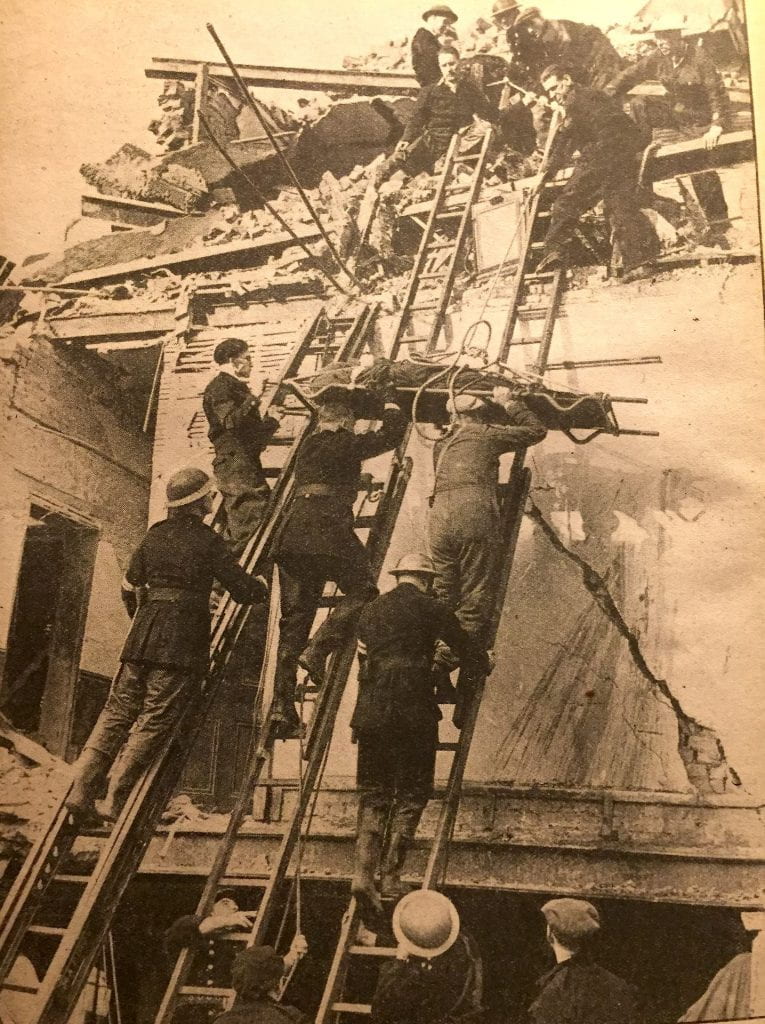

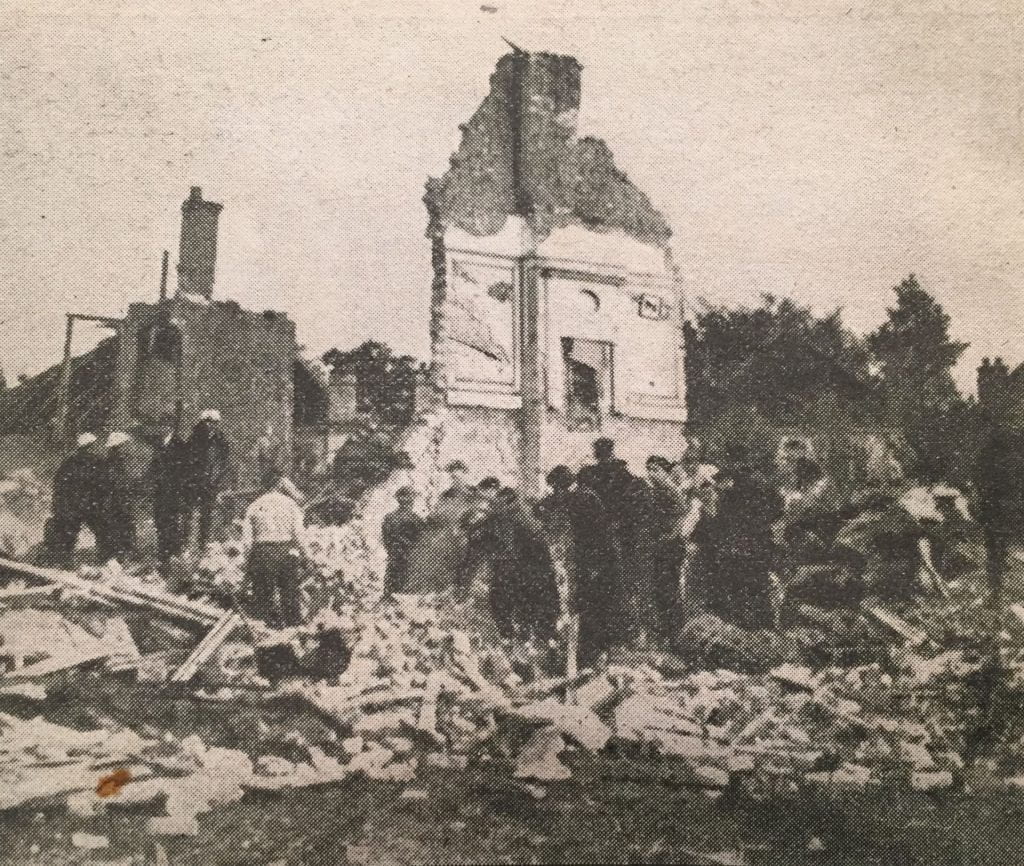

National Fire Service people and Heavy and Light Civil Defence rescue squads search for survivors of a V2 rocket bomb on London during the autumn of 1944. Image: War Illustrated.

A V2 rocket bomb which descended from the sky on the Woolworths and Coop stores in the New Cross Road Saturday lunch-time 25th November 1944 became the most devastating Home Front disaster caused by the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile.

New Cross experienced mass destruction of buildings and human life.

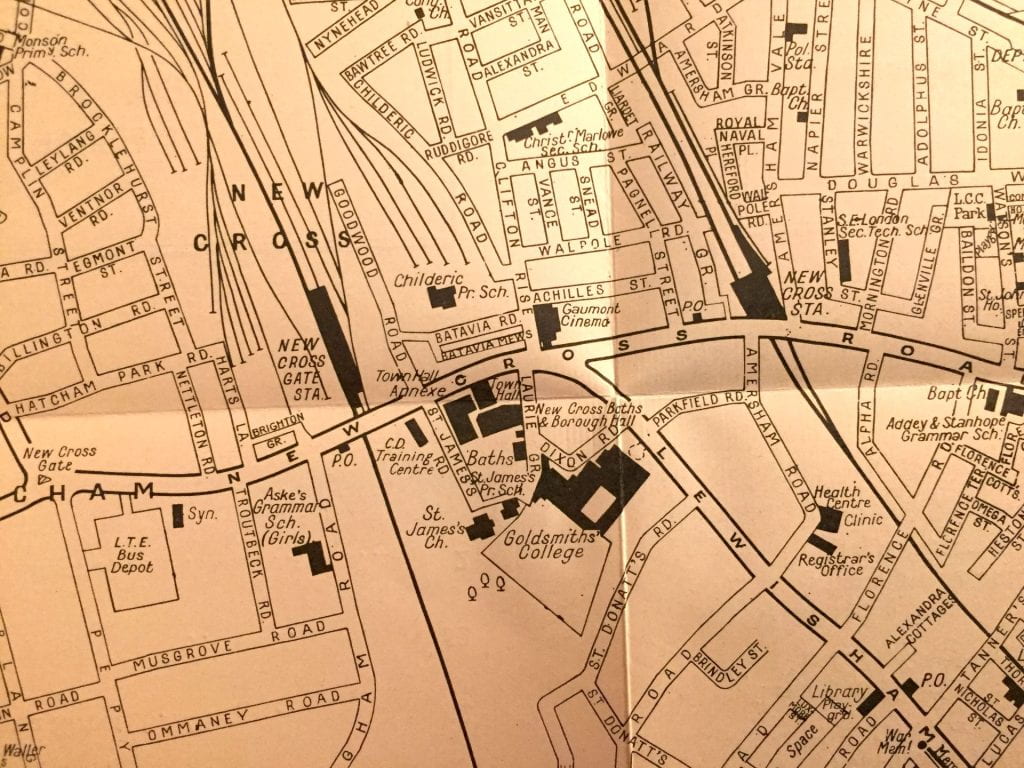

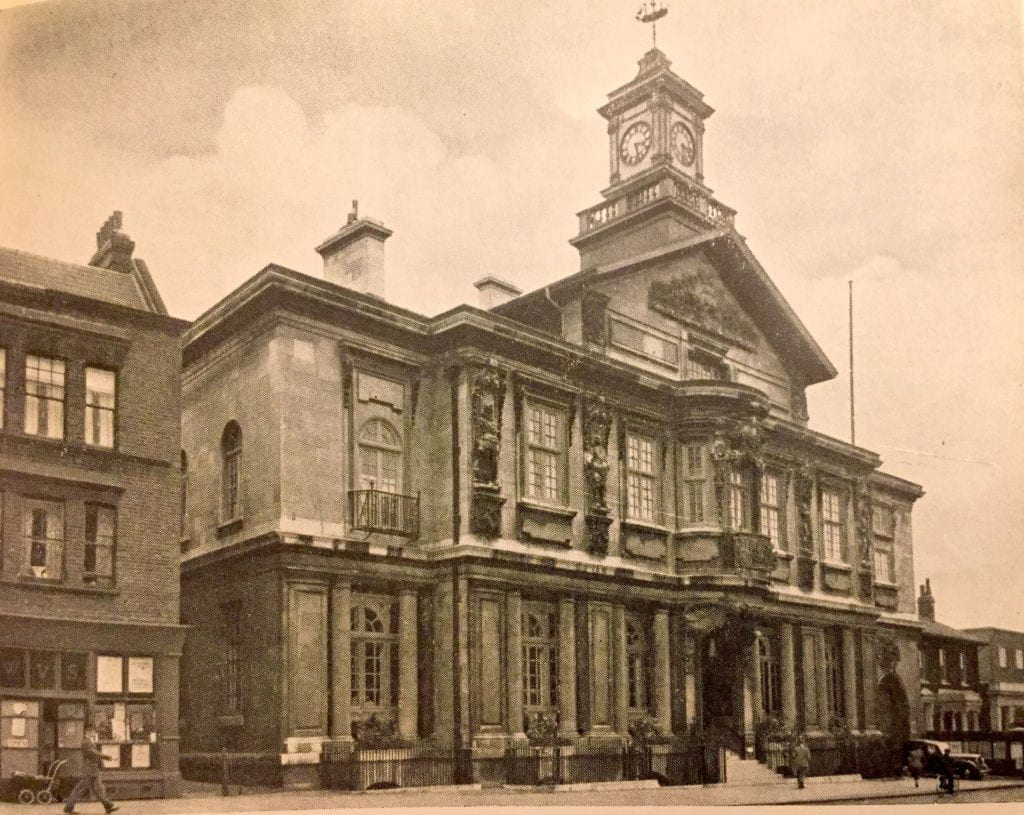

This catastrophic event happened a stone’s throw from Deptford Town Hall, now an important building used for teaching by Goldsmiths, University of London.

The people’s history dimension of this event is more bound up with the history of Goldsmiths than has hitherto been fully appreciated.

Goldsmiths now owns the site of the former St James’s Church, which has been converted into gallery and teaching spaces and is part of the memorial and human geography of what happened in the Second World War.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

Much has been written about an event which tore the heart out of the local community; largely because so many women and children died. Norman Longmate in his book Hitler’s Rockets: The Story of the V2s devotes pages 207 to 212 to a detailed description and analysis along with eye-witness accounts.

After WW2 Deptford Borough Council set about rebuilding on the site of the Woolworths tragedy and by 1947 the building now standing was constructed enabling Woolworths to return to the New Cross Road and with the provision of two storey maisonettes for council tenants above. Image: Goldsmiths History Project

But there is little evidence now of what happened either by way of commemoration to those who died or tribute to those who took part in the rescue operation. Lewisham Council Local History and Archives Centre lists the details of those who died and could be identified. It seems 23 could not.

Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

There are plaques which briefly state ‘In memory of the 168 people who died and those injured in the V2 rocket attack that landed here 25th November 1944.’

This had been the 251st V2 rocket successfully launched into Britain and counted as one of the worst civilian disasters of the Second World War.

People died in the pancaked Woolworths store and Coop next door.

An army lorry was overturned and destroyed and everyone sitting in the number 53 double decker bus and those at the bus queue were struck down.

Debris stretched from Deptford Town Hall to New Cross Gate station and it took three days to retrieve all the casualties.

Mrs Barbara Smith told the BBC’s WW2 People’s War Project:

‘One Saturday morning I was visiting a friend near my home. As I arrived at her door, a V2 fell. I said to her, “I must hurry home, that was a V2.” It had fallen at the bottom of my road on the Woolworths store in New Cross. As I hurried home I saw many people who were injured, and others were dead and lying on the pavements and in the road. Ambulances and fire engines were parked nearby, attending to the injured and dying. The air was filled with grit and dust. There was a huge crater on the Woolworth site where the V2 had fallen.

The first four houses in my road [Goodwood Road] were demolished. We were number 9 and my house was badly damaged, a four storey Victorian house, but it was still standing. The tall flight of front steps were damaged, windows fallen out, ceilings down, furniture damaged. How thankful I was that my family was alive and only slightly injured. Unfortunately the dog was missing. She had run out when the V2 fell.

I had been at the Woolworths store visiting every Saturday morning with a friend, but that particular Saturday, I’m glad to say that I hadn’t gone.’

St James’s Church is the nearest church to the location of the disaster.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

A new church building is situated nearby. Again the memorial to Deptford’s fallen in the Great War is in tablet form with names inscribed.

The victims of the Blitz in the Second World War are memorialised by an open stone book on a plinth and a garden has been planted in memory.

By 25th November 1944 the media were no longer fully shackled by censorship. Even the BBC’s Audrey Russell was sent to the scene to record interviews and make a voiced report though the acetate discs of her work have not survived and the recordings seemingly never broadcast at the time.

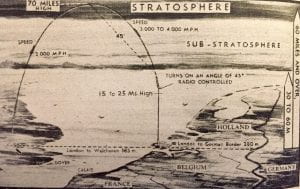

War Illustrated used graphics in a publication in late December 1944 to explain how the V2 rocket was fired some 60 to 70 miles into the sky and came down from space at 2,000 miles an hour.

The rescue and salvage operation was among the biggest to be mounted in London. 100 National Fire Servicemen attended, including George Roberts from New Cross, multiple cranes, and heavy and light rescue squads from Deptford and surrounding boroughs.

The entire First Aid Post operation headed by Dr. Knight and situated in purpose built headquarters at Barriedale to the north side of the Goldsmiths College grounds coordinated the emergency medical services.

By Monday 27th November national newspapers published reports though still avoiding any identification of the specific location.

The News Chronicle‘s headline was ‘Bomb In Crowded Street Killed Women Shoppers- Chain Store Was Demolished.’

“Women and children, busy about their shopping were killed recently when a bomb fell in a crowded street in Southern England. Dead and injured were scattered about the roadway.

A chain store, which was one of two shops demolished, and another large store, which was badly damaged, were filled with customers, mostly women and children.

A large proportion of the fatal casualties occurred in those two shops and in the road outside, where a passing bus was wrecked.

Fire in the ruins hindered the rescue squads, who toiled through the night, clearing wreckage with the aid of cranes.

Thirty hours after the bomb had fallen bodies were still being brought out of the ruins.

Apart from those killed or seriously injured, many received minor injuries from flying glass and falling masonry.

Mrs Bessie Payne, who occupied a flat over the badly damaged store, with her five-year-old daughter Beryl, was buried.

“I was in the kitchen,” she said, “when the walls collapsed and the ceiling fell on me.

“I was buried almost up to the neck, but by wriggling violently I managed to free myself. Then I hunted through the choking dust until I heard Beryl crying.

“She was nearly buried, but I managed to free her. I have lost everything, but I am lucky to be alive and to have Beryl safe.”

The Daily Mirror‘s front page headline was ‘Bomb Hits Stores’:

“Through a winter afternoon and night and on into the following morning grim-faced men kept toiling to release women and children believed to be buried in the debris of a multiple store in Southern England hit by a V-bomb recently.

The bomb fell when the shop was crowded with mothers and children, many of them doing their Christmas buying. Fatal casualties were numerous, and many injured were taken to hsopital.

The same bomb also wrecked another store and families had to be rescued from the explosion-stripped skeletons of their homes facing the store.

Women queuing outside a fish shop nearby were swept over by the blast.

Twenty hours after the bomb fell, rescue squads were still digging in the glare of mobile lighting units.

Red-eyed rescue men who had been working furiously for fourteen hours dug with renewed speed as a woman’s voice drifted up through the debris. She was dead when, later in the afternoon, they got her out.

The crater left by a V2 bombing in London at the end of 1944. Image: War Illustrated.

Two cranes pulled away girders and raised giant buckets of debris, uncovering the last remaining victims amidst crushed saucepans and household goods which the women had been examining when death struck.

Near the rescuers, treated almost with reverence by the grimy men, lay a pathetic little pile of children’s fairy stories, nursery rhymes and painting books.”

The Daily Express reported:

“Ambulances stood silently by as rescuers worked with hydraulic cranes. Nearby lay a little pile of children’s fairy stories, nursery rhymes and painting books. Beside them, salvaged intact, were rows of tumblers, bottles of lemon squash, tins of evaporated milk, packets of envelopes and assistants’ invoice books. Price cards were scattered over the road and trodden underfoot.”

Another dramatic eye witness account was provided to the TimeReel ITN documentary London’s War: The Road To Victory in 2010:

“I remember seeing a horse’s head laying in the gutter. And further on, there was a pram hood all twisted and bent.

And there was a little baby’s hands still in its woolly sleeve. Outside the pub, there was a bus. And it had been concertinaed. Rows of people were sitting inside all covered in dust and were all dead.

I looked over to where Woolworths had been, and there was nothing. There was an enormous gap, clouds of dust and I could see right through to streets beyond.

But there was no building; just piles of rubble and bricks. The only thing still standing was the Coop. And it was still settling.

And the rubble and debris was still settling down and from underneath all that, I could hear people screaming.”

Images of the destruction and aftermath have been archived by Lewisham Council.

These include a view of the wrecked houses on the corner of New Cross Road and St James’s.

Then there is the view of the obliterated Woolworths store on New Cross Road, what is left of the Coop and being able to see through to Batavia Road.

A few days after the debris clearance the photograph below provides an open view from half way down Goodwood Road to Deptford Town Hall. The entire corner of Goodwood Road and New Cross Road has been flattened. Three huge metal containers are on the roadside which had been used by heavy cranes to clear most of the rubble.

The devasation and salvage operation after the V2 rocket attack on the New Cross Road 25th November 1945. Image courtesy of Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre.

Another photograph shows the devastation and destruction from Batavia Road looking across the flattened Woolworths site over New Cross Road towards St James’s with the church in the far distance. A small piece of the shelving from the ground floor premises of Woolworths has survived.

A fifth photograph presents the scene from the Deptford Town Hall side of New Cross Road, with the tramlines in the road, to half of what is left of the Co-operative Society store and looking over to the flattened site of Woolworths and wreckage of houses on the other side of Goodwood Road.

The Mary Evans picture library licences photographs preserved in the London Fire Brigade museum.

There are six high resolution and dramatic pictures of National Fire Servicemen engaged in the rescue operation working in smoke and debris, and these are curated in the site’s search facility under the reference ‘Goodwood Road’.

There are two panoramic daytime scenes in Goodwood Road and New Cross Road showing the heavy lifting cranes and smoke still billowing up from a fire at the back of Woolworths. It can be presumed these were taken on the day after the V2 struck.

The victims and their identification

This is a new work in progress investigating and exploring the ancestry and life traces of each and every one of the people who died in the V2 disaster. These were people who made up the humanity of New Cross and neighbourhood in 1944. They had heritage and families. They had jobs, lived in homes and had futures. They constituted the very heart of the community. They had voices, dreams, hopes, fears and souls. They were and are much more than mere names and statistics.

The plaques and memorials cite 168 people who died. The Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre lists 144 named casualties with ’23 or 24 others who could not be identified.’

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records names and details for 147 casualties for 25th November 1944 and then provides records of three further deaths in the three days which followed. These were seriously injured victims who died in hospital. One fatality is also located with a place of death at Goodwood Road.

Consequently, 151 named individuals can be listed as victims of the bombing. The issue of a remaining 17 people never being identifiable requires further inquiry. During the London Blitz it was not unknown for people’s bodies to be destroyed by blast and incineration, or indeed, in macabre terms, to be dismembered and mutilated beyond the extent that they were capable of identification.

However, even given the fact we are dealing with forensic pathology of nearly 80 years ago, medical and coroner’s services were usually very skilled in eventually ensuring that every missing person was accounted for.

Where no trace of a missing person’s body could be found, it was law and practice for the Coroner to hold an inquest and issue a verdict as to their fate.

Longmate’s book quotes from a report compiled by ‘the casualty services officer from regional headquarters’ that at Deptford Town Hall ‘an improvised collecting post for casualties and first aid post came into being.’

The V2 rocket detonated at 12.25 p.m. The report states ‘the heavy mobile first-aid unit, in charge of Dr Knight, from Barriedale FAP [First Aid Post] was called at 12.38’ and arrived a few minutes later.

The report also states: ‘The original mortuary having been destroyed, a temporary mortuary was established at the premises of Pearces Signs, to which bodies and fragments of bodies were taken.’

It is not clear which mortuary the report’s author is referring to in terms of ‘having been destroyed.’

The Pearce Signs’ building had been badly damaged and it can be presumed it would have been used as a preliminary collecting point.

Deptford Council had specifically converted the Goldsmiths College swimming pool for the purpose of being used as a mass casualty mortuary. It had been damaged in Blitz incidents, but it was not fully destroyed by fire until May 1945.

Since the Goldsmiths’ College campus was effectively Deptford’s emergency medical services headquarters with the new Barriedale building constructed in the early 1940s to add to the resources, it is possible the converted swimming pool could have been used.

On the other hand the previous damage may have been so great they were forced to find somewhere else to do the distressing work. Such a situation must have been so frustrating and challenging.

To assist with identifying over 100 fatalities additional mortuary staff had also been seconded from Bermondsey and Lewisham.

Remembering those who died

23 year old Kathleen Alice Adsley lived with her father Joseph, mother Alice and older brother Edward at 11 St. Norbert Green, Brockley, Lewisham. Born in New Cross in August 1920 Kathleen worked as a dressmaker. Her father worked as a general labourer in the highways section of Deptford Borough Council. She was clearly successful in her work because at the relatively young age of 23 she left an estate worth nearly £175 which in today’s values is the equivalent of £10,663.63 (13th November 2023).

16 year old Evelyn Lillian Amos lived with her parents Frederick and Edith at 1 Cranbrook Road, Deptford. Frederick was a bus conductor and Evelyn’s older brothers William, a coal heaver, and Stanley, a shop assistant were also living at home.

48 year old Frances Ellen Axton (maiden name Shorey) was living with her husband Charles Arthur Axton at 34 Oareborough Road, New Cross. She was born in Deptford on 12th March 1897 and at the time of the 1939 Register was living at number 5 Oareborough Road with the occupation of ‘unpaid domestic duties.’ Oareborough Road no longer exists. It was an L-shaped street of terraced houses demolished to make way for Folkestone Gardens. She began working after leaving school at the age of 12 and by the time she was 15 she was packing chocolate. Before her marriage she was an assembler working for Wincles Operators. She married Charles in 1922 who would outlive her by 34 years when he passed away in Southwark in 1978.

71 year old Frederick William Bailey like many of those who were killed, resided only a few minutes walk away at 13 Jerningham Road. In 1911 Mr Bailey was working as a grocer’s assistant and living with his family at 24 Oareborough Road- previously mentioned as one of the lost streets of Deptford and now the site of a park. He was 37 years old and his wife Lily a year older. They had three children, daughter Florence, aged 15, and sons Frederick, 12, and Edwin 10.

42 year old Florence Ethel Banfill died in the rocket attack along with her son who was only three years old. Her husband Bartholomew was left grieving for the loss of his wife and young son. They lived in nearby 19 Childeric Road New Cross. Bartholomew, who was 40 years old at the time, worked as a storekeeper for a builders merchant. Florence had lived in Childeric Road most of her life. She married Bartholemew in 1929. He would pass away in Bromley in 1977 at the age of 75 outliving his first wife and son by 31 years. He did however remarry Constance Brent in Lewisham in 1951.

3 year old Brian John Banfill of 19 Childeric Road New Cross as outlined above died with his mother Florence in this air raid disaster.

30 year old Robert Bass from 84 Douglas Way in Deptford died from the injuries he received in the blast after being taken to the Miller General Hospital in Greenwich High Road. He was married to Jessie Victoria Bass who was 31 at the time. The house they lived in is no longer standing and part of the Margaret McMillan Park. Robert was a deal timber porter and the V2 bombing left their sons, 9 year old Robert and 7 year old William, without a father. Jessie remarried in 1946 to 28 year old Leonard Bedford who was a New Cross resident and worked as a ‘reinforced contractor’ in the building trade.

61 year old John James Bateman was a Police Sub-Inspector assigned to the Air Ministry living at 203 Rochester Way, Blackheath. He had served in the Duke Of Cornwall’s Light Infantry during the Boer War of 1899 to 1901 and re-enlisted for the Great War of 1914-18 in the same regiment with the rank of Corporal, Acting Warrant Officer Class 2. He was awarded the Silver War Badge and other campaign medals, and after the war pursued a career in the Metropolitan Police reaching the rank of sergeant in Lewisham in 1939. He left probate in 1946 of £1,000 which in today’s values is the equivalent of £51,647.22.

74 year old Elizabeth Lillian Jane Beaton was living at 186 New Cross Road at the corner of Pepys Road. She was the widow of William Beaton and originally came from Hampshire. Her father John Harris had been a boilermaker for a Portsmouth naval dockyard. Born in Brighton, Elizabeth’s parents had brought her up on Portsea Island before moving to the Mile End area of the port. Her late husband William had been a bricklayer and they had married in Portsmouth in 1893. Elizabeth had had two younger brothers Alfred and Arthur who started their working lives as errand boys. Elizabeth had been a corset maker and she and William moved to Eastleigh at the turn of the century where he got a bricklaying job with a builder’s firm. They had two children, Lillian Gertrude May and William Edward who were 46 and 43 respectively when she was killed in the New Cross Road V2 attack.

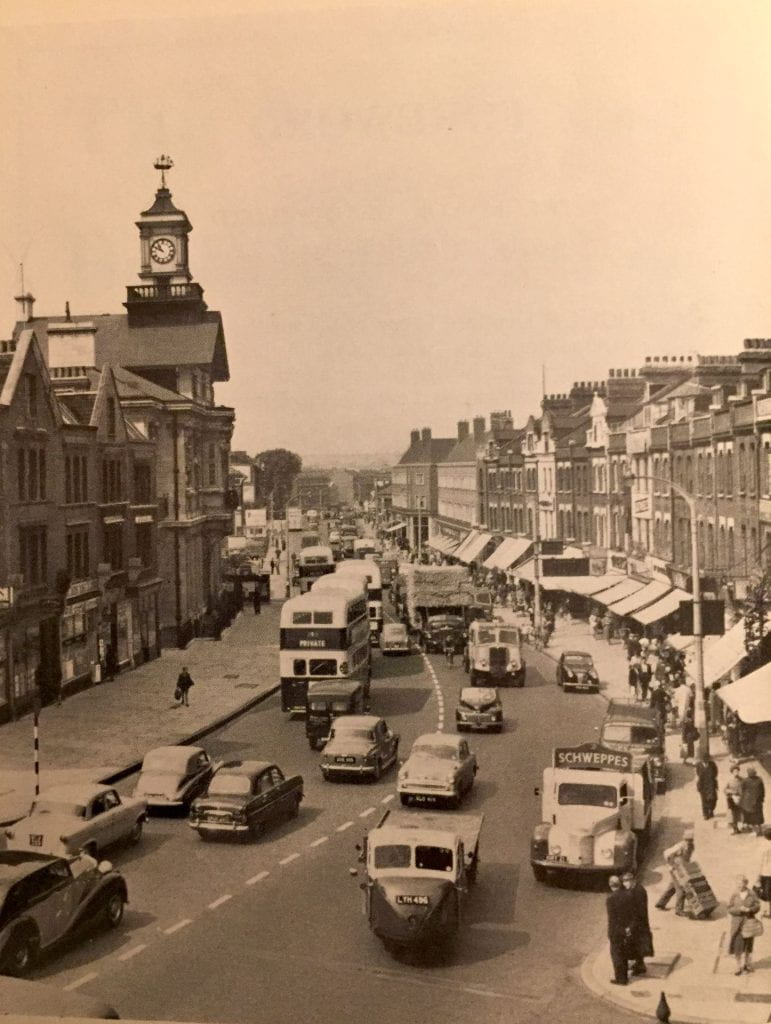

New Cross Road looking down from the Gaumont cinema towards Deptford Town Hall on the left with the location of the Woolworths V2 attack beyond. Photograph was taken in the middle 1950s. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

31 year old Harriet Amy Bentley lived at 7 Cambridge Drive in Lee. Harriet was born Harriet Duffy 17th May 1913 and worked as a drapery shop assistant. Her father was a carman working for Lion Cartage in Bermondsey and she was brought up at 28 Reculver Road, Deptford in a large family home with five sisters and two brothers. The original house is no longer standing and the street entirely rebuilt. She was only 20 when she married 49 year old printer’s compositor Albert Edward Henry Bentley in Deptford in 1934. Bentley had been a mechanic in the Royal Naval Air Service and RAF during the First World War and would outlive her by 18 years when he died in New Cross General Hospital in 1962 at the age of 77.

51 year old Theodore Ludwig Berning was a married man living at 32 Downhill Road in Catford. He had been born and brought up in London’s East End Jewish community starting out his working life in 1911 as a salesman at the age of 17. This was a part of London experiencing overcrowding, poverty and deprivation at the time. In February 1909 there is a reference in a local newspaper to ‘a lad of 15’ named as Theodore Berning appearing before the Thames Police court for stealing cash from automatic gas meters. He had told the magistrate he was ‘only looking for a job.’ His German born father William had been a trouser presser and he was brought up in a household with two brothers and three sisters in the St George in the East district of Wapping-Stepney which is now in the Borough of Tower Hamlets. In 1901 his 15 year old brother William was working as an office boy and his older brother Henry, 17, as a tailor’s apprentice. It seems Theodore was switching his forename in the public records with ‘Frederick.’ If this is the case he married Dorothy Elizabeth Leatham in 1917 and they had a son called Theodore Frederick in 1918. They were living 29 Thirza Street Ratcliff in 1921 and Theodore was working as a cinema attendant at the Ballaseum in the Commercial Road. Electoral rolls last recorded Theodore Berning living in this part of East London up until 1931. It seems possible he reappeared in the public records as Frederick Berning, a packer for food produce manufacturers, living with his wife Elizabeth in Waltham Forest in the autumn of 1939. Their son Theodore Frederick W Berning enlisted in the Army and was posted as a missing but found casualty in France in 1940 with the rank of Acting Corporal in the Royal Army Service Corps. An Elizabeth Berning, who is likely to have been Theodore’s widow, passed away in Bromley in 1977 at the age of 79. She had survived him by 33 years.

60 year old William John Bradford had been living with his wife Catherine at 6 Headley Street, Peckham. The house and street no longer exist. Headley Street used to run west from Gordon Road, north of Sturdy Road and is now a path in Consort Park. William was a window cleaner working on his own account and had married Catherine Duff in Camberwell in 1915. Catherine had been born in Dublin. They had a daughter Kathleen who was 28 when her father was killed by the V2 bombing. Catherine Bradford passed away in Camberwell in 1974 at the age of 86.

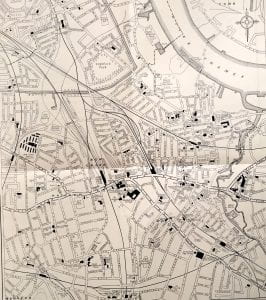

Post WW2 map of Goldsmiths’ College in Deptford showing the locations of the College, Deptford Town Hall and V2 rocket attack. Image: Goldsmiths History Project

37 year old Florence Elizabeth Harriet Branscombe was living with her mother Elizabeth Branscombe at 9 Raymouth Road, Rotherhithe. Her father Frederick James Branscombe, who had been a fish curer, passed away when a pensioner at the age of 76 in 1943 in Camberwell. The V2 rocket disaster left Elizabeth at the age of 67 grieving for her husband and adult daughter in less than a year. Florence had been a shop assistant. Her surviving older brother, also called Frederick, worked in the Lyons Confectionary Company’s chocolate factory in Shepherdess Walk, Clerkenwell. Elizabeth Branscombe died in Lewisham in 1966 at the age of 89, some 22 years after her daughter’s terrible death.

67 year old James Henry Bradon was the husband of Louise May Bradon and they both lived at number 42 Comerford Road in Deptford. The terraced Victorian house is still very much looking on the outside as it was in 1944. James was a Thames Lighterman-who are special boatmen or sailors of the river who carry goods on the Thames. They ‘lighten’ (that is, unload) a ship and transfer her cargo to another vessel, or to shore. They are also the working brothers of Thames Watermen who carry people and their goods. Both Lightermen and Watermen are members of the same City of London Company which was originally constituted many centuries ago. James was born in Greenwich in 1877 and baptised at Christchurch in East Greenwich. His father Charles William was a barge builder. James Henry married Louise May Tansley from Portland in 1903 and by 1911 they were living in Deptford Green with their son James Charles and Constance Francis. By 1921 they were living in Rotherhithe New Road with James working for the Thames Steam Tug Lighterays Company and his son James Charles also working there as an apprentice Lighterman at the age of 17. By 1939 and the beginning of the Second World War, the family had moved to Comerford Road and they were letting out rooms to a shipping clerk and three people working for a sugar confectionary company. After her husband’s death in the V2 raid, Louise May continued living at 42 Comerford Road until her death in 1965 and left an estate of £3,102 which in November 2023 was worth £74,069.55. Her son James Charles Bradon was by then a well-established and respected Thames Lighterman and Waterman.

65 year old Andrew Poulton Brazier was living with his 72 year old wife Elizabeth at 43 Manor Avenue, Brockley which at the end of September 1939 had multiple occupancy. Public documents show his actual age was 67 as he was born 24th October 1877. Lewisham’s Local History and Archives Centre state he was ‘a civil defence worker.’ In 1939 he described himself as a textile commercial trader and throughout most of his working life he had been a commercial traveller. When he was 23 in 1901 he was working as an assistant in the silk department of a large store. His father, also called Andrew Poulton Brazier, was a hosier manager and the large family, including his mother, three working sisters and one brother were living at 41 Cressingham Road, Blackheath. His older 28 year old sister Lily was working as a teacher. By the time of the Great War Andrew had volunteered as a gunner for the Royal Garrison Artillery and his army records state he was a widower with ‘one boy’ who served in France in an anti-aircraft company. The 1911 census had recorded him living with May Lucy (née Potter) in Twickenham whom he had married in the same year and she had been working as a mantle maker. They had a son Andrew Robert Brazier in 1912. It seems May Lucy Brazier died in Kensington the following year within a year of her son’s birth. Andrew Poulton Brazier remarried Elizabeth Gooden in 1920 and they were living with his son from his previous marriage in Nunhead at the time of the 1921 census. He was still working as a commercial traveller specialising in drapery. During the Second World War Andrew Robert Brazier served in the army as a lance-bombardier and his father’s estate of £147 in effects, worth £5,242.01 in October 2023, was left to his stepmother Elizabeth.

6 year old Nicholas Oliver Bright was the only son of George, 49 and Grace Bright, 47, who were living at number 44 Peckham Hill Street, Peckham. Their house is no longer standing and is the site of a Burger King fast food restaurant. Nicholas was born on 28th November 1937 in Camberwell and was actually killed on the day of his mother’s birthday and three days short of his own. It is possible that he could have been a signwriter and painter like his father. It was a family tradition. His grandfather Walter Ellis and great uncle Walter Arthur had been sign writers as well. George Bright married Grace Millwood in Camberwell in 1920. Grace was a tin worker employed by John Feaver tin manufacturers in the Tower Bridge Road. George Bright passed away in Ramsgate in 1958. He was 63. Grace died in 1992 at the age of 94.

31 year old Ivy Brown lived at 48 Evelina Road, Nunhead with her husband George Henry Brown. They married in 1941. It seems Ivy was shopping either in Woolworths or the Coop with her 18 month old daughter Joyce who was also killed in the V2 bombing. Ivy was the daughter of a First World War hero- Private William Eastman who was killed in action 3rd May 1917 in Chérisy, France when a private serving in the 8th Battalion East Surrey Regiment on the Western Front. He had been awarded the military medal for bravery. The fighting at Chérisy village, was part of the Arras campaign in the Pas-de-Calais area of France. William had been in the 18th Division which captured it from the Germans on the 3rd of May 1917, but then lost it the same night. Ivy was only three when her father was killed. Before the war he was a greenhouse hawker working in the old Convent Garden fruit and vegetable market when it was situated in the Soho area of London. He volunteered for service in 1914 at Deptford Town Hall, and the Imperial War Museum hosts a portfolio of images of him at work as a hawker, in uniform, and a family picture with his wife and children. This image most likely includes a photograph of Ivy when she was an infant with her mother Alice Maud, sisters Elsie and Alice, and brother William. Her brother can be seen next to her far right. It is a poignant turn of fate that Ivy’s daughter would be killed at roughly the same age Ivy was when this photograph was taken and three generations of William Eastman’s family, including himself, would be destroyed by the violence of war in the 20th century. In the case of his youngest daughter and granddaughter this would happen not when they were in uniform in battle but on the Home Front while shopping. The family lived at 55 Selden Road, Nunhead during the Great War. By the beginning of the Second World War in 1939 Ivy was living at number 22 Selden Road with her two sisters. Ivy was 26 years old working as a wax paper machinist along with her sister Alice. Her eldest sister Elsie was working as a laundry folder and checker. Their mother is believed to have passed away in 1925. The Selden Road they lived in during the first half of the 20th century has been largely redeveloped.

18 month old Joyce Brown was the daughter of Ivy Brown who died in the same incident and is profiled above.

12 year old Sylvia Rosina Brown was the younger daughter of 43 year old Albert John and 41 year old Lilian Gertrude Brown, and they lived at 56 Oareborough Road in Deptford. Oareborough or Oareboro Road, as has already been explained, is now a lost road or street of Deptford having been cleared to be part of Folkestone Gardens. Lilian and Albert married in Greenwich in 1927. Sylvia was born in Deptford on 11th January 1932 to very hard-working parents. Her father was a timber porter and described as ‘heavy worker’, and mother was a factory hand for Armour Mills in Lewisham which manufactured lace and silk goods. In her young life Sylvia went to Elementary School in Deptford, and would join her mother every summer in the hop-picking holiday tradition of many thousands of east and south-east Londoners. When war broke out in September 1939 that’s where Sylvia was with her mother Lilian staying in the Hopping Huts at High Tilt Farm near Cranbrook in Kent. She was then only seven years old. They would have travelled out there and back on one of the South Eastern Railway and London Chatham and Dover Railway Hop Pickers’ Specials from London Bridge which would transport Londoners to the towns and villages at the centre of the hop-growing agricultural industry mainly in Kent, Surrey, Hampshire and Sussex. The final chapters of W. Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage and a significant part of George Orwell’s A Clergyman’s Daughter include evocative fictional accounts of London families taking part in the annual hops harvest. In Orwell’s case his writing could be described as documentary as it is based on his personal experience and the diary he kept of joining hop-picking families one summer in the early 1930s.

- Hopper huts at Grange Farm, Tonbridge. By Dr Neil Clifton CC BY-SA 2.0

- Hopper huts at Downs Farm, Yalding. These had integral fireplaces. By Penny Mayes. CC BY-SA 2.0

While Sylvia, her mother, 11 year old sister Lilian Edith and other relatives were still in Kent finishing up the hop harvest at the end of September 1939, her father Albert was working in London and staying in Trundleys Road, Lewisham. Sylvia’s sister Lilian was 16 at the time of the V2 disaster, would marry Walter Mackenzie in 1947 and would pass away at Hope Close in Grove Park, Lewisham in 1990 at the age of 62 leaving an estate of £115,000 which in today’s values is the equivalent of £271,761.07.

40 year old Maud Alice Bush of 27 Pepys Road, New Cross Gate, Deptford was the daughter of Henry Bush. She was critically injured in the V2 explosion and taken to the Miller Hospital in Greenwich but died from her injuries on the same day. Public records indicate Maud’s mother Alice Maud Burningham married Henry Charles Bush in Camberwell in 1902. Maud Alice was born in Peckham 20th December 1903 with her twin sister Winifred. She was single and a working woman all her life until it was cut short by the V2 rocket blast. She and Winifred worked as skilled machinists in the clothing industry for Messrs Rogers, a well-known manufacturer of shirts. Her father, known to his family as ‘Harry’ had been a railway inspector for the South Eastern and Chatham Railway which had a monopoly of railway services in Kent and to the main Channel ports for ferries to France and Belgium before merging with other railway companies to form Southern Railway in 1923 which on nationalisation after WW2 became the Southern Region. By 1921 Harry appears to be living on his own at 60 Haydock Road, Deptford with his four daughters, Maud Alice and her twin sister Winifred, both 17, Nellie Mabel, 15, Florence Ivy, 13, and 33 year old housekeeper Blanche Frances Charlesson from Cork in Ireland. There was also a ‘paying guest’ called Elizabeth Marmion working as a cashier for one of the famous J Lyons and Company teashops and Corner Houses. Nellie Bush was an apprentice at ‘Fancy Needlework’ for Haywards. Mother Alice Maud may have moved away or passed away. By 1939 and the outbreak of WW2, the household was more or less the same at 27 Pepys Road, but now all women and minus Harry. Again, it is possible he had passed or moved away. 51 year old Blanche Charlesson was described as doing unpaid domestic duties. Elizabeth Marmion, 57, was still there and working as a cashier for J Lyons. Three of the Bush sisters, Maud, Winifred, and Florence were working as machinists, and Nellie was now a full-time needleworker. Another woman had moved in, 58 year old welfare worker Alice Fowler.

44 year old Reginald Bradford Calder had a dramatic and adventurous life. At the time of his death he was living with his 42 year old wife Violet Hagen Calder and two daughters at Greenways, The Glen, Farnborough Park, near Orpington in Kent. The Glen is and was a private road of well-to-do houses. Detached homes in this private gated estate sold for more than £3 million in 2023. Reginald was an accountant and auditor. A track of newspaper articles reveals in 1924 he was acquitted of hitting his mother when she went for him with a dagger in an extraordinary domestic dispute, was hailed a hero for rescuing men from drowning in Barmouth, Wales in 1936, fined for speeding in 1941, and then killed in one of the worst V2 rocket bombings of the London Blitz on 25th November 1944.

The Bromley and West Kent Mercury published a charming obituary about him on 1st December 1944 saying he had ‘many friends in City circles and in Bromley and Catford where for many years he lived at 83 Daneby Road as a practising accountant before moving to Farnborough Park. The Mercury said he was ‘greatly respected for his professional capacity and his personal qualities. He was one of the kindest and most helpful men, as many can testify, and his passing will be sincerely regretted.’

He served with the Gordon Highlanders during WW1 and in 1920 was appointed secretary of the ‘Services Rendered’ Club in Greenwich. He married Violet Hagen Winter in Greenwich 1924. Violet was the adopted daughter of William and Eleanor Greenway and had been brought up at their home, 10 Deloraine Street, Deptford. William worked as a flusher and then watchman for the London Country Council. Deloraine Street is another ‘lost street’ of Deptford in the sense there are no longer any houses there, just allotments. It seems they were pulled down because of war damage from bombing during WW2.

Violet was a Clerk and Policy Typist for the Licenses and General Insurance Company on Victoria Embankment next to Temple Station when she met Reginald. She found she had married into a family full of domestic drama.

Only a few months after they wed in 1924 there was an explosive row at the Calder family home in Reading, Berkshire. Reginald’s father Herbert and younger brother had been locked out by his mother Winifred. Reginald and Violet had driven from London to try and help sort things out after getting a desperate phone call from his father and arrived at a quarter to one in the morning. It is an indication of his success that at the age of 24 he could afford to drive a fast car in only the second decade of motoring and had his own phone at home.

A policeman was also outside the house, 197 Cranbury Road, having been called to the disturbance. Reginald forced back the catch of a window to get in but when doing so, his mother turned to the officer and insisted ‘Constable arrest him! He is wanted for fraud all over London.’ There had been a background of marital trouble between Herbert and Winifred, Winifred accusing him of domestic violence and in the turmoil of families experiencing such internal conflict Winifred’s two daughters sided with her mother and Herbert’s younger son living at home, Dudley, sided with him.

Reginald at 24, having flown the nest and just married, found himself in the middle. After much shouting through the night the battle recommenced in the morning. Winifred insulted her daughter-in-law Violet with ‘a rude and wicked remark.’ Winifred claimed Violet pushed her and thumped her. Reginald claimed Winifred produced a dagger, he held her wrists, asking Violet to take the knife from her, as his mother said nobody would be leaving the living room alive. In the ensuing struggle, mother was disarmed and, said her son had given her a black eye. She prosecuted him for assault at the Borough Police Court. Every attempt to reach a settlement beforehand had been unsuccessful. Winifred admitted she did have a dagger, but to do herself in if her husband started to ‘knock her about.’ Her youngest son Dudley did not help her case when he said his mother ‘had a mania for daggers and razors.’ The Magistrates dismissed the case against Reginald, and Winifred left the court in tears.

Reginald’s father Herbert was also a larger than life character having been born and brought up in what was then the colony of British Guiana, which on independence in 1966 became Guyana. In the 1890s he was working as a ‘fifth class clerk’ in the government’s Land Department. His first marriage to Ida Isabella Calder in Guiana lasted only three months, largely because he travelled to England and met Winifred. In 1898, the Supreme Court of Guiana in Georgetown, Demerara granted an uncontested divorce to Ida for one of the shortest marriages on record there. At the 1924 court hearing Winifred accused Herbert of being divorced after only three weeks of marriage on the grounds of adultery. Herbert pointed out that if there had been any adultery, it had been 4,000 miles away from the spot and would have been with Winifred when he was in England.

Herbert had stayed in London after his divorce from Ida in British Guiana, lived with Winifred and eventually married her in 1902. He joined the London County Council as a tram conductor operating out of the New Cross Tram Depot. By 1911, they were living at 13 Trinity Grove Greenwich with their six children, Herbert William Leslie aged 12, Reginald Bradford aged 10, Gordon Alexander aged 7, Gladys Vera Anne aged 6, Dudley Richard aged 4, and the then infant Mona Lily Maria not even a year old. Herbert’s job as a tram conductor saw him appear in court a couple of times. Once in 1905 when he was accused of overloading his tram in the Old Kent Road and acquitted, and again in 1911 when an unruly passenger was fined for attacking him. The fight broke out when Herbert had gone to help pick up a child slightly hurt after snatching a free ride and then jumping off and falling over.

The Reading dagger incident of 1924 had not been the first time the Calder family’s fiery domestic rows had played out in court. Two years earlier, the Greenwich Police Court, later Greenwich Magistrates, had to resolve a situation where father Herbert Lindsay Calder had this time locked out Winifred and their two daughters. Winifred was suing for a separation order on the grounds of desertion. By 1922 Herbert Lindsay Calder had left the trams, served as a clerk for the RAF during WW1, had injured his thumb while in service, received £350 in compensation, and was now ‘an artist.’ Winifred said not very tactfully that he was more of an illegal bookmaker, ‘backing horses and running a book’ by taking bets from punters.

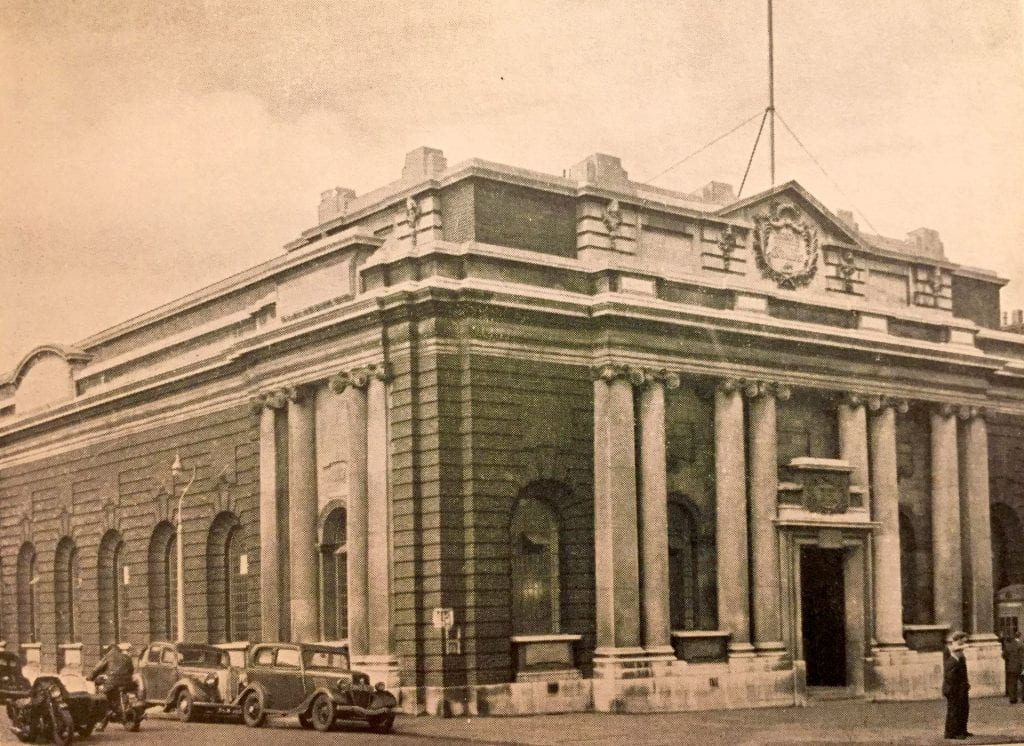

The entrance to the old Greenwich Police Court, later Greenwich Magistrates. Image by Tim Crook for the Goldsmiths History Project.

This court case arose from an incident where a local postman had called the police after seeing Winifred out on the street in the rain with two of her daughters and a pile of her clothing that Herbert had thrown out after her. Winifred complained that he had threatened to murder her if she came back.

Herbert Calder told the Greenwich Magistrates that indeed he was an artist but ‘there was nothing doing just now in that direction’ and he was out of work. He said Winifred was ‘an impossible woman’, that they never spoke to each other in the house except when she chose to use ‘filthy language.’ Winifred said that he had fallen for another woman, something he denied, and he said she had told his children that he was not their father and they had ‘another daddy.’

The voice of mediation came in the form of the Calder’s eldest son Herbert William Leslie, then 23 and having been an engineer in the RAF at the end of the Great War. He gave evidence to explain that his father ‘was a very fine man’ and had only struck his mother once some 14 years before due to provocation. He said his mother Winifred ‘was a good mother in many respects’, but when she lost her temper she had a habit of threatening members of her family with a knife which they often had to struggle to take from her and she had also threatened to poison them with arsenic. The Magistrate decided to dismiss the summons and let the family sort out and indeed live with their differences. As we know issues came back to court two years later and the question of knives, or in that case, a dagger, arose again. Then the second son, Reginald Bradford, had to intervene.

There is a happy end to the story of Herbert Lindsay and Winifred. They did stay together and live with each other’s temperaments. By the time of the Second World War in September 1939, they were living at 69 Melbourne Grove in Dulwich. Herbert was now 67 years old and working as a ‘wine traveller’ and one of their daughters, Mona, now 28, was a professional dancer and still living at home. Herbert would pass away in 1948 at the age of 76 having lived four years longer than his second son Reginald killed by the V2 at Woolworths in the New Cross Road.

The sad postscript though in respect of Winifred is that in 1952 she put an advert in the Sydenham Forest Hill and Penge Gazette: ‘Widow (late Herbert Lindsay Calder, traveller) homeless four years, unable to get two unfurnished rooms or one large with kitchenette; over four years on Lewisham House List; old resident Lewisham before being bombed out. Please help- Mrs. Calder, 8 Moatlands House, Cromer Street WC1.’

The 1930s were a boom time for accountant auditor Reginald Bradford Calder and his wife Violet. The cars got bigger, the houses larger and more salubrious and they had two daughters. They were on holiday in Barmouth, North Wales in July 1936 when a swimmer got trapped in seaweed and three men who launched a boat to rescue him got into trouble when it capsized. Reginald and Violet were on the beach among the hundreds of holidaymakers watching and hearing the cries of the stricken swimmer and then the boat turning over with his rescuers in the choppy seas. Reginald swam out to them with another holidaymaker and brought them all safely to shore. His heroism would be reported in the Daily Mirror and regional press.

The kindness of his personality averred to in his obituary was in evidence during the trial of a nurse prosecuted for stealing Violet’s clothing from their house in Catford in 1933. When Reginald heard the Detective Sergeant who caught her red-handed saying she had pleaded: ‘Please give me a chance. I don’t know what made me do such a thing’, Reginald told the court he had no wish at all to press the charge ‘if it was her first lapse.’ It turned out, however, Iris Mary Good had not been good, had not been a nurse at all, had got the job in the Calder household on false pretences and could have done more harm than good as she had no training as a nurse. She was eventually tried at the Crown Court, found guilty and sent to Holloway Prison for nine months.

It is not clear what business Reginald was on that Saturday lunchtime 25th November 1944 when he was killed by the V2 rocket. Perhaps he had been speeding down the New Cross Road in his car on the way to the City or West End, or he had been sitting on the number 53 bus when it too was destroyed in the blast.

My reference to his possible speeding is based on the fact he was fined thirty shillings (£1.50 in today’s currency) in April 1941 for driving too fast in Bromley. It was unusual for non service personnel to be able to afford to run a car during the war years. If his car was caught in the blast, might it have been possible he was driving more cautiously than normal so as to avoid committing another motoring offence and this was why he would die in the explosion?

His widow Violet would remarry Herbert E Gibbs in 1956 and she would pass away in Bromley in 1979 at the age of 77, some thirty five years after she lost her first husband in the V2 attack.

Reginald Calder’s death in the New Cross V2 disaster was obviously a terrible blow to his family, but the talented Calders more than stepped up to the fight against Hitler and the Nazi regime that was causing so much death and suffering through its indiscriminate bombing of London and the rest of Britain.

Reginald’s two younger sisters Mona Lily Marion and Marjorie Leonora, born in 1911 and 1915 respectively, became professional dancers and performed and entertained in theatres and music halls throughout London and England during the war years. Mona would later recall to her daughter incidents where she was often only seconds from stepping off a tram before an area was bombed.

The contribution of the country’s entertainment industry in maintaining and boosting civilian morale may not have received the same recognition as ENSA’s work with frontline troops. It merits full appreciation.

The Crown Unit’s documentarist Humphrey Jennings recorded for posterity the dimensions of this service in the 1942 film Listen To Britain. From the moment you see two servicemen sitting on a bench overlooking the sea, the gradual fade-up of dance-music montages into the sequence of elegant ballroom style dancing which was a huge recreation and escape for people at this time.

And the culture of sartorial and dignified dancing elegance was exemplified by Marjorie Leonora who in her professional name of Lola Cordell teamed up with Alan Gold whom she would later marry.

People aspired to dance like the enthralling Gold and Cordell. As Pathé News said in 1939, just after war had been declared, Gold and Cordell in their performance of ‘Drawing The Line’ were ‘reminding you of the time when dance was an elegant thing. Judge for yourself!’

Pathé would bring the couple back into their studios in 1941 to film another ‘graceful presentation from that talented pair Gold and Cordell’- and said this with a flourishing emphasis on their names.

The Pathé production in these films was of the highest standard using the latest camera and lighting techniques. The narrator talked about how the dancing ushered everyone ‘into the world of romance’ and said of Gold and Cordell: ‘two stars with twinkling feet.’

Marjorie and her sister Mona lived long and successful lives. Mona passed away in 2014 at the age of 103 and Marjorie in 1997 at the age of 87.

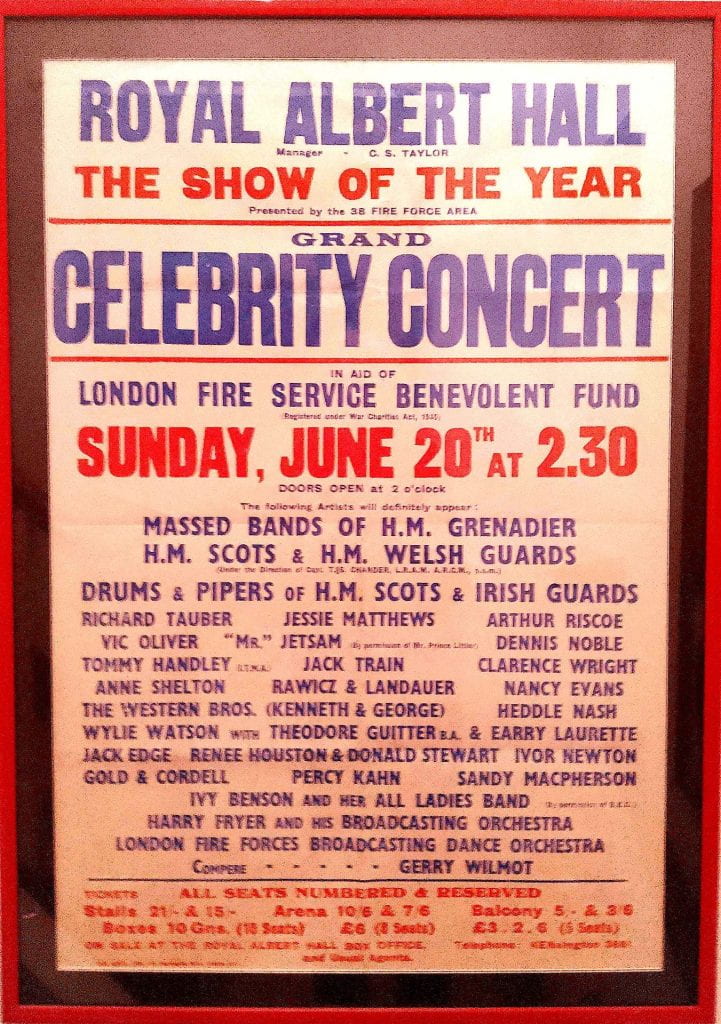

Gold and Cordell featuring in this poster for the ‘Grand Celebrity Concert’ at the Royal Albert Hall on 20th June 1943. Image: Courtesy of Diane Robb.

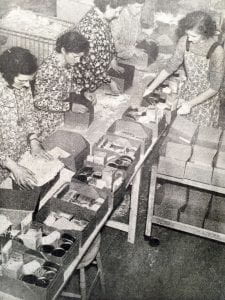

21 year old Doris Eileen Edith Card worked for the British Red Cross Society during World War Two and her duties could have included being a First Aid Post (FAP) nurse and helping to organise and pack Red Cross parcels for British Prisoners of War abroad. Her father was 55 year old London Passenger Transport Board bus driver Walter James Card, and her mother was Jane Elizabeth Card who was 47 at the time of the V2 bombing. Doris lived with her parents and 23 year old sister Gwendolyn at the family’s semi-detached home in number 36 Olron Crescent in Bexley.

Red Cross First Aid Post nurses going to a bombing incident in London in the spring of 1941. Image: War Illustrated, April 1941.

Gwendolyn Jessie Alice Card was a shorthand typist and part-time ARP Warden with Bexley Council. She would marry Clifford Langley in 1945. Gwendolyn would live long enough to enjoy her 95th birthday before passing away in Bridgnorth Shropshire in 2016. Doris Card’s father outlived her by ten years passing away in Bromley in 1954.

Members of the Red Cross Society making up Red Cross parcels for British POWs in London during WW2. Image: War Illustrated 1941.

Her mother Elizabeth Jane née Bannister was brought up in a large family with six brothers and one sister in Deptford where her father had been a railway coalman for the South Eastern and Chatham Railway.

She was 23 years old when she married Walter Card at the end of 1921 and had been working as a general servant in her parents’ home at 50 Railway Grove Deptford, which would ironically also be damaged beyond repair by another V2 rocket bombing at the end of October 1944. She would outlive her daughter Doris by 54 years and passed away in Shrewsbury in 1998 at the age of 100.

26 year old Mary Carroll was an Irish woman living at 24 Girton Road, in Sydenham, Kent. She was the daughter of James and Norah Carroll, of 15 St. Laurence’s Terrace, Lower Grange, Waterford, in the Irish Republic. Her family home in Waterford is now part of a convenience grocery store. She is commemorated in Waterford’s Rolls of Honour for people killed during the 20th century’s two world wars.

40 year old Joan Ivy Singleton Clamp was killed when working in the offices of her husband’s firm Clamp and Son at 280 New Cross Road- almost opposite Woolworths and the seat of the V2 rocket bomb explosion. Joan was a successful professional surveyor living with her husband, the auctioneer Ernest Edward Clamp, in the well-to-do neighbourhood of Sandilands in Croydon Surrey. Their house at number 39 is still standing. In 1944 it was a symbol of the affluent suburban building boom of the 1930s where successful middle-class people bought their own detached houses with large gardens and could still afford to hire a live-in servant. In the example of the Clamps, the September 1939 Register records that Mary Wells, then 34 years old, was there working and living with them as their domestic servant. Mary would have been their effective housekeeper- cooking, cleaning and most likely doing their shopping. In 1947 Mary would marry John Gallagher in Croydon.

The Clamp and Son building at 280 New Cross Road was destroyed in the V2 explosion and Deptford Borough Council constructed a special one storey Civil Defence headquarters building in its place on the corner with St James’s. Fast forward to the present it is now the site of Goldsmiths Loring Hall of residence for the university’s students. The bus remains in the same position. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

Joan Clamp was born in Uxbridge, the daughter of grain merchant Edwin Singleton Brame and her mother was Kate Ivy née Hosking. Joan was brought up in Surbiton with her three younger sisters Kathleen, Margaret, and Dorothy. All the Brame daughters had the second middle names of their parents.

Ernest inherited his family’s well established firm of auctioneers and estate agents which in 1901 was based at 65 New Cross Road. It had been founded by Ernest’s grandfather in 1849. In 1901 his father Richard described himself as a furniture dealer and bailiff and Ernest had two brothers and a sister. By 1921 his father had passed away and he was living with his mother Margaret at 98 Maple Road Surbiton which is where he met and married Joan Brame in 1923. He was 33 and she was 18.

In 1923 Ernest inaugurated the opening of the New Cross Gate Auction Mart, built to the designs of architect J Halstead Waterworth at 280 New Cross Road, almost opposite New Cross Gate station. The new Messrs. Clamp and Son venture was celebrated with a ‘smoking concert’ and included a live music programme. Joan Clamp developed her surveying career in her husband’s firm working as clerk and assistant to the Estate Manager and Surveyor.

Various adverts for Clamp & Son between 1922 and 1955.

By the time of Ernest Edward Clamp’s death in 1953, Clamp & Son auctioneers were still trading from 394 New Cross Road opposite New Cross station– which was the last headquarters of the business. Ernest died at the age of 63 still grieving over the loss of his brilliant wife Joan in the V2 bombing nine years before. It is not believed they had any children.

When Joan was killed she had accumulated an estate reported for probate in May 1945 at £4,168. This is worth £148,630.69 in the values of 3rd December 2023. Her friends and family decided to raise a bequest for the Croydon General Hospital in her name. It was reported in the 5th May 1945 edition of the Croydon Times:

‘Memorial to V2 Victim: Plaque in Croydon General Hospital

A plaque will be erected in Croydon General Hospital to the memory of Mrs Joan Clamp, who was killed in November last, when a V2 bomb fell at New Cross. This memorial is the result of a fund which raised £170 as a gift to the hospital from Mrs. Clamp’s relatives and friends.

Entrance to Croydon General Hospital. Early 20th century postcard. Public Domain.

The words to appear on the memorial plaque will read: “Erected by the friends of Joan Clamp in affectionate memory, 25th November, 1944- through enemy action.”

The Board of Management are deeply grateful to those who chose this method of keeping her name in memory, and by which the hospital is greatly assisted in its efforts to prolong and save the lives of others.’

Croydon General Hospital joined the NHS in 1948 and the building was demolished in 2004. It is not known what happened to Joan Clamp’s plaque. The site is now the location of the new Harris Invictus Secondary School.

42 year old Henry Charles Cole was described as a corporal in the Home Guard in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission file on his death by V2 enemy action at 12.26 on Saturday 25th November 1944. He was the husband of Violet Marie Cole and they were both living at 20 Revelon Road, a terraced Victorian house in Brockley at the time of his death.

The 1939 Register records that he was also a volunteer for the Auxiliary Fire Service- clear evidence of his sacrifice and commitment to civilian defence. Henry was working as a ‘motor driver’ with a light vehicle licence and they were living in 73 Gellatly Road, Nunhead.

He had been born 10th November 1902. Violet was a couple of years younger having been born 4th December 1904. They married in Greenwich in 1924. Violet née Dinmore had been brought up by her uncle, painter and decorator William Mears in 34 Maxted Road, Peckham with her three cousins William, Sidney and Phoebe.

Henry’s father Charles William was still living in the family home 24 Linden Grove, Camberwell at the time of his son’s death in 1944. He was a widow as Florence Clara Cole had passed away at the age of 45 in 1922. Henry’s younger brother, also called Charles William, was living with his father and working as a radio despatch clerk. Henry had two sisters Helen Florence and Florence Kezia. His father had been a machine driver for the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company manufacturing Sub Marine cables in 1921 and in his later life worked as a carpenter. When Henry Charles was 18 he was working for Leyland Motors. Henry’s widow Violet passed away in Croydon in 2004 at the age of 99, some sixty years after her husband was taken away from her by the V2 bombing in the New Cross Road. They did not have any children.

71 year old James Alban Cole was a confectioner and tobacco dealer with his own shop at 182 Bellenden Road in Peckham. It is still a shop, currently a pizza restaurant called ‘Made of Dough’, and previously a hairdressing salon called ‘Chaz Hairdressers.’ At the time of his death he was living with his wife Kate at number 167 Peckham Rye which is no longer a stand-alone house but the site of a modern block of apartments.

James Alban Cole was born in Homerton/Hackney in 1873. His father Fletcher was a carpenter from Suffolk. James Alban was a commercial traveller and salesman throughout his working life and settled down in what would be most people’s retirement years in Peckham to run the tobacco and sweet shop in Bellenden Road. James met and married furniture assistant Kate Judges at the Holy Trinity Church in Sittingbourne, Kent in 1902 where her father Frederick was also a carpenter and joiner and gave her away at their wedding. James was 28 and Kate 23.

She was brought up in the family home at 7 Station Street in Sittingbourne. The house is no longer standing and the site has been redeveloped. James and Kate had one son, Stanley Alban Cole, born in December 1913 and at the start of the Second World War he was working as a clerk in an engineering works. He was 31 when his father was killed by the V2 rocket. He passed away in Stevenage in 1995 at the age of 81.

Deptford Town Hall facing the location of the Woolworths V2 blast site during the Second World War. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

45 year old Frederick William Cornford was a machine fitter and moulder living in a Victorian terraced house at 94A Bovill Road, Forest Hill, Lewisham which is very much the same as it was in 1944 apart from all the modernisations and maintenances expected over the passage of nearly 80 years. His death would leave a widow and teenage daughter grieving. Doris Cornford was 41 and their daughter Muriel 16. Frederick and Doris had married in Lewisham at the end of 1927. Doris née Cooper would pass way in Lewisham fifty years later in 1994 at the age of 90. Doris was brought up in a huge working class family living in various addresses in Chaplin Street, Forest Hill. She had four sisters and three brothers. Her father Thomas was a chimney sweep who died at the age of 46 in 1908 when Doris was only 4 years old.

Frederick was born in Lewisham in 1899 and brought up at 9 Dalmain Road Lewisham by his parents William Henry and Agnes Mary. The street has been rebuilt since the Cornfords were living there in the early part of the twentieth century. William worked as plasterer for the Pitcher Construction Company in North London. Frederick was always a machine worker- effectively an engineer- and employed by Key Glass Works in Cold Blow Lane adjacent to Millwall’s old football ground when he met Doris. The Deptford and Lewisham area was still the centre of much engineering and manufacturing industry during the early to middle 20th century and Frederick was very much part of the large local skilled workforce employed by it. He had four younger sisters, Florence Emily, Linda Elizabeth, Katie Lilian and Ethel. One of the cruelties of the V2 atrocity is that Frederick Cornford’s parents outlived him. His father William Henry died in Lewisham in 1967 at the age of 92, and his mother Agnes passed away in 1960 aged 82- decades after their son’s death on the Home Front. Frederick’s only daughter Muriel would marry Norman Collett in 1952. How Muriel must have wished her father could have been alive to give her away at her wedding some eight years after the terrible event in the New Cross Road.

18 year old Queenie Doris Cox was a docker’s daughter, one of three sisters born in Lewisham to parents Reuben and Florence Cox. At the time of her untimely death Queenie had been living with her parents in the London County Council tenement block at 12 Cayley Close on the Honor Oak Estate in Lewisham.

Many of the tenements of this interwar council estate have been demolished including Cayley Close where Queenie was brought up with her sisters Ruby and Iris. Her father Reuben had to rise early in the morning and attend the wharfs and docks on Thames riverside for what was known as ‘the call-on’ from large gatherings of dockers hoping to be picked for work. This was the tough tradition and insecurity of dockland employment for labourers at this time. Several men were often competing for every job and older men would usually be passed over. The working conditions were hard and there would be no compensation for injuries at work which were common. Wages would be paid in public houses with corruption behind the scenes when dockers bribed stevedores to guarantee being hired for jobs. Reuben would ply his docker’s trade at Butler’s Wharf on the south bank of the River Thames, just east of London’s Tower Bridge, now housing luxury flats and restaurants.

Butler’s Wharf on the south bank of the River Thames, photographed from Tower Bridge in London by Oosoom CC BY-SA 3.0

Queenie died on 25th November 1944 at an age when she was promised so much in terms of the life ahead of her. There is evidence she was good at school. At the time of the 1939 Register census, she and her older sister Ruby were staying with Council Watchman Christopher Balcombe and his wife Maud in their country house called ‘The Sheding’ on the Rabies Heath Road in Bletchingley near Godstone, Surrey. As Ruby and Queenie were still at school this may well have been the result of their wartime evacuation. Sister Iris, who was eight years old at the time, stayed with their parents in London.

Queenie’s parents Reuben and Florence married in Lewisham in 1924. Reuben was 23 and Florence 28. Reuben was from a working class Bermondsey family closely connected with Thames River trades. In 1921 his older brother Robert was an unemployed seaman and three sisters, Ethel, 14, Emma, 11, Edie, 9, and youngest brother Alfred, 7, all living at home with parents Thomas Henry and Alice Sophia Cox at number 52 Enid Street, a house long since demolished to make way for the Neckinger Estate.

Florence or ‘Florrie’ as she was known to friends and family, outlived her daughter Queenie by 31 years, passing away in Southwark in 1975, aged 79. Reuben lived another 37 years after Queenie’s death by enemy action and also died in Southwark six years after his wife in 1981, aged 80. And what of Queenie’s sisters? They would both have long lives. Iris Violet, who was only 13 when Queenie was killed, would marry Gerald Donoghue in Deptford in 1950. She died in Sussex in 2008 at the age of 77. Older sister Ruby Florence married Edwin Pratt in Lambeth in 1948. It seems she married again and passed away as Ruby Florence Scott in Croydon in 2006 at the age of 81.

48 year old Horace Alfred Crisford was a veteran of the First World War and WW2 Special Constable. A year before his killing by V2 explosion he and his wife Edith had received the worrying news that one of their sons, Laurence, had been wounded in battle while serving in the British Army in Italy as a driver with the Royal Artillery.

Horace had been born in Southwark in 1896 and served as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps in France during the Great War receiving the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal and Victory Medal which he wore with pride every Armistice Day and as ribbons on his Special Constable’s uniform. His family had been working class. His father Robert had been a market basket carrier in Bermondsey. By the time of the 1911 census Horace was 15 years old and had started his working life as a shop assistant.

For most of his working life Horace had been the delivery driver for Elizabeth Handley-Seymour of New Bond Street, distinguished dressmaker to the Court, who designed for the Royal Family, aristocracy and theatrical celebrities of London from the 1910s to 1940, when she retired.

Horace’s employer was glamorous and famous, and best known as the designer who made the wedding dress of the Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother) and later, her Coronation dress in 1937.

Image: File: Queen Elizabeth Bowes Lyon in Coronation Robes by Sir Gerald Kelly. Created: between 1938 and 1945 date Public Domain

Horace’s wife Edith née Johnson in New York City and was seven years older than him.

At the time of the 1939 Register, the beginning of World War II, the whole Crisford family were living at 20 Cranfield Road in Brockley, a semi-detached late Victorian house still standing and looking on the outside as it did when Horace’s widow Edith learned of her husband’s death on 25th November 1944.

In late 1939, their sons Laurence and Robert were still living at home. Laurence, who had been born in 1918 was working as a clerk in the Royal Victoria Victualling Yard in Deptford, and Robert, born in 1923, was a clerk working for a poultry maker.

The cruelty of Horace’s death at the end of 1944 is that he would be denied the privilege and pride of seeing his sons’ marriages. Robert Edward married Ellen Munck in Salisbury Wiltshire in 1945, and Laurence Alfred married Phyllis Jarvis Humphrey in Newnham, Sittingbourne in Kent in 1947. Charming reports of the marriage and reception appeared in local newspapers: ‘When the couple left for their honeymoon at Folkestone, the bride wore a grey costume with blue accessories. Her handbag was a gift of the bridegroom (Laurence’s brother Robert). The bride’s gift to the groom was a signet ring. Mrs and Mrs Crisford’s future residence will be London. Many useful presents, money, and cheques, were received by the happy couple, and several congratulatory telegrams. The groom has spent the last five years in the Army overseas, while the bride was for four and a half years a member of the W.A.A.F.’

There is something enormously nostalgic and poignant in seeing the weekly local newspaper for the village of Newnham take the trouble to report: ‘The bride, who was given away by her eldest brother, was charmingly attired in a white satin gown with a full length veil and a coronet of orange blossom, and carried a bouquet of pink and white carnations and fern.’ The loss of local newspaper journalism in recent decades means people no longer have the privilege of this kind of reporting.

Horace left probate worth £461 which in today’s money is worth £25,209.92. When his widow Edith passed away in East Grinstead in 1982 at the age of 93, her estate of £25,000 would be worth £108,807.35 today.

Their sons had long and fulfilling lives. Laurence died in Bungay Suffolk in 2012 at the age of 93 like his mother, and Robert had passed away in Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire at the age of 84 in 2007.

38 year old George James Alfred Daniels was born on the Old Kent Road in 1906 into a family steeped in the traditions of the printing trade. His father Frederick was a vellum binder working for the Drayton Paper Works in Fulham. George began his working life from the age of 14 as an errand boy and then joined his father in the printing industry and by 1939 he was a printer’s guillotine cutter.

He married Lilian Maud Belcher in Deptford in 1934. Lilian was working as laundry calenders hand at the time of his death and they resided at 36 Burchell Road in Peckham- an end of terrace late Victorian house adjacent to what is now the George Mitchell Primary School. A calenders hand in the laundry trade was somebody who folded by hand work after it had been taken off the ‘calender’, or ironing machine.

Lilian had had a tough upbringing in Peckham and Bermondsey. Her father Arthur had been a bricklayer’s labourer and died when she was a child. Her mother Katherine had to work as charwoman at the time of the 1921 census, with her oldest son Arthur Lewis, then 18, working as a porter for Cheamers Furriers and looking after Lilian, her younger sister Hilda and brother William.

Lilian was left on her own when her husband George was killed in the V2 explosion. They had not had any children. George left probate of £187 to her which in today’s money (December 2023) was the equivalent of £10,226.15.

Lilian was 37 years old when George was killed. She never remarried and passed away in Lambeth in 1978 at the age of 71.

38 year old Kathleen Isobel Davies was a near neighbour of Goldsmiths’ College, University of London. She lived with her husband, William Frederick Davies, at 23 Barriedale, New Cross, round the corner from the specially built base for emergency medical squads sent to air raid incidents in Deptford including the one which would claim her life.

Kathleen was born in Charlton on January 13th 1906 and her parents Vincent and Ella Cockram hailed from Somerset and Devon. Her father Vincent began his working life as a nurseryman and assistant gardener and by the time of the 1901 census he was working in Hayes , Middlesex. He married Ellen Sorton at St Mary’s Church in Uffculme Devon on Boxing Day 26th December 1903. He was 26 and she was 24.

By 1911 the young family was living at number 37 Bolan Street in Battersea. Vincent was a park gardener employed by the London County Council. The houses in Bolan Street were severely damaged during the Blitz and the street’s post WW2 demolition led to the loss of the name with the area being incorporated into the new Ethelburga Estate.

During the First World War, Vincent Cockram served in the British Army’s Cyclist Corps and later in the Royal Army Service Corps. He survived the conflict and was demobbed in 1919.

His daughter Kathleen Isobel Cockram married William Frederick Davies in Stoke Newington in 1931. She was 25 and he was 27. William worked as a shipwright.

In 1936 they had a daughter Beryl and at the beginning of the Second World War, Kathleen and Beryl evacuated with her mother to Devon. At the end of September they were staying at 62 Lime Tree Walk in Newton Abbott. William Frederick stayed in London and carried on working while living in Barriedale, Lewisham.

It is presumed Kathleen and Beryl returned to London following the first Blitz of late 1940 and early 1941. How tragic that Kathleen would be killed in the second Blitz of flying and rocket bombs in 1944, leaving her daughter Beryl, now 9 years old, to be brought up by her single parent father. William Frederick would carry on living at 23 Barriedale, Lewisham until his death at the age of 84 in 1988. He left a probate estate of £68,090, which in 2024 had a purchasing power of £231,914.39.

64 year old Arthur Thomas Doswell was living at 45 Endwell Road, Brockley and the husband of Annie Louise Doswell.

Arthur was a veteran of the First World War having served as a private in the Scots Guards in the very first year in France with embarkation there on 11th November. He was awarded the 1914 Star, British War, and Allied Victory medals which were nicknamed ‘Pip, Squeak and Wilfred’.

Arthur was brought up in a large Camberwell family living at 57 Bournemouth Road. His father, also called Arthur Thomas was a silversmith and polisher and his mother Mary originally from Kent. At the time of the 1881 census, the Doswell family household included his 15 and 5 year old sisters Emily and Mary Elizabeth still at school, and his three year old brother Henry. There were five other people lodging in the house which has long since been demolished and redeveloped.

His wife Annie Louise Campbell also hailed from a large Camberwell family. In 1901 when she was 19 years old and working as a boots paste fitter she was living with her parents at 27 Graylands Road with seven younger sisters and her 17 year old brother Joseph who was a brass finisher. Graylands Road no longer exists having been replaced by council estate development.

She married Arthur Doswell in 1906. By 1921 Arthur and Annie were living at 59 Kimberley Avenue, Nunhead [The house has been replaced with a modern terraced bungalow]. Arthur was a carpenter and joiner for Wallington Jones Cold Storage. They had two daughters Annie and Alice and a son also called Arthur.

At the beginning of WW2 in late September 1939 they were still living in Kimberley Avenue. Arthur’s son was now working as a railway clerk. They had moved to 45 Endwell Road during the war and Annie remained living there as a widow until her death in February 1951 at the age of 69. She left her estate of £316 and 16s to her son Arthur Alfred Doswell, now working as a civil servant, which when taking into account inflation would £8,241.87 at the time of writing (19th March 2024).

31 year old Doris Violet Drain

59 year old Henrietta Frances Dyer

29 year old Edith Phyllis Edwards

Deptford High Street between the First and Second World Wars of the twentieth century. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

55 year old Alice Christina Errington

57 year old William Arthur Farr

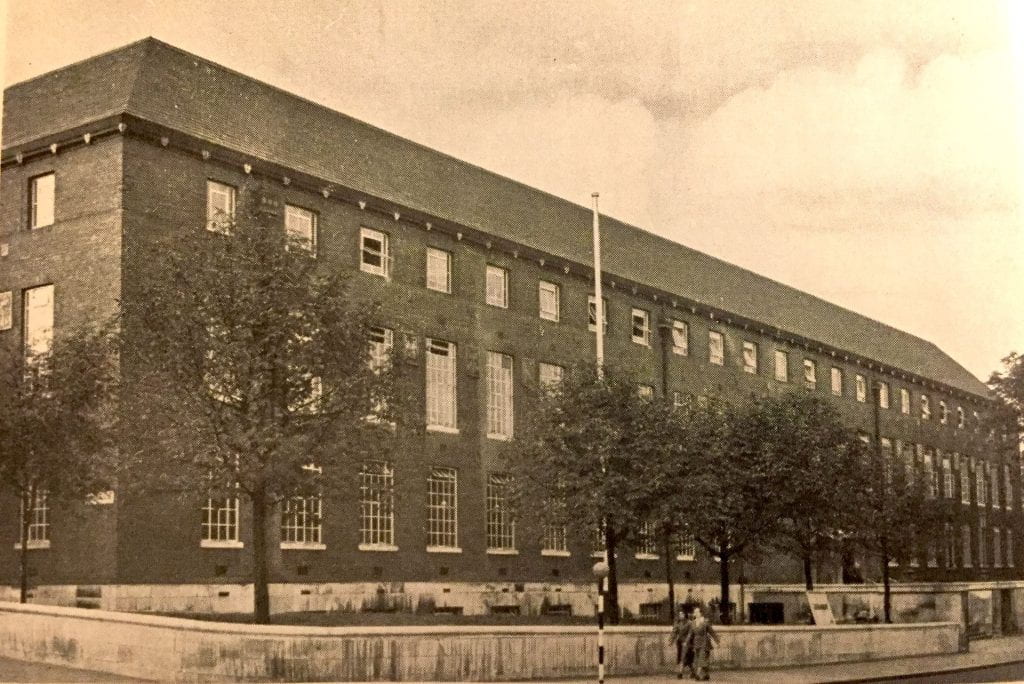

The newly repaired and rebuilt Goldsmiths College main building in 1947. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

45 year old Matilda Caroline Fish

17 year old Jean Caroline Maud Fish

69 year old Henry Abraham Fitch

31 year old Kathleen Frances Fitzpatrick

3 year old Carol Ann Fitzpatrick

60 year old William Charles Fletcher

First V2 rocket to strike England impacted on Staveley Road in Chiswick at 6.49 a.m. on the 8th of September 1944. Initially, it was thought it might have been a gas explosion, but the shrapnel and fragments of the rocket recovered revealed the true nature of the menace. Image: War Illustrated 1945.

44 year old William Walter French

3 year old Kenneth Albert Gibbs

44 year old May Marguerite Glick

27 year old Julia Elizabeth Glover

1 month old Michael Thomas Glover

46 year old Dorothy Elizabeth Griffiths

Map of Deptford Streets during World War Two. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

52 year old Agnes Augusta Grout

36 year old Ivy Josephine Gurr

32 year old Thomas James Gushlow

49 year old William Thomas Hammond

17 year old Ruby Josephine Hansford

Other parts of London experienced the terror and destruction of V2 rocket attacks. This is the aftermath of one such incident at the famous Smithfield meat market in the City of London in 1944. This is now the location of the new incarnation of the Museum of London. Image: War Illustrated 1944.

16 year old William Herbert Hastings

37 year old Ivy Gertrude Hayes

53 year old Grace Eleanor Hayter

42 year old Alma Ellen Heading

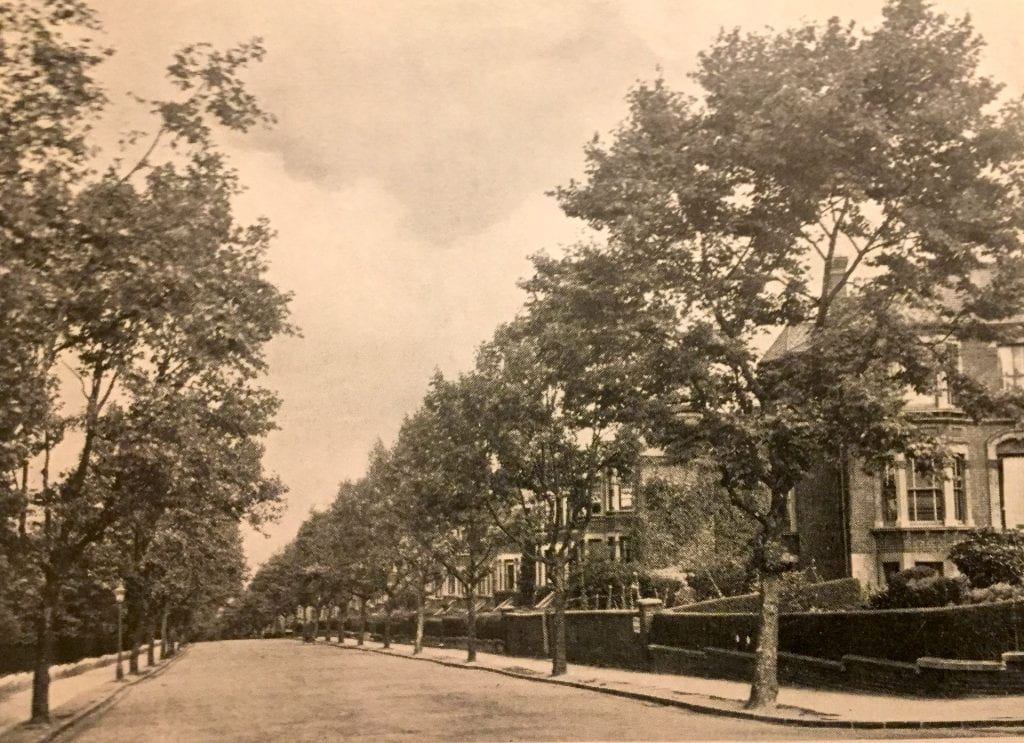

Pepys Road in Deptford during the 1930s. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

18 month old Malcolm Robert Herbert

32 year old Maud Ellen Louisa Horrigan

66 year old Walter Federick Humphrey

34 year old Edna Beatrice Jarmaine

62 year old Florence Jessie Kelsey

11 year old Ronald James Kenwood

33 year old Florence Maud Kirby

50 year old Annie Elizabeth Kirby

Junction of New Cross Road and Lewisham Way with tram lines and police officer controlling the traffic. Image from circa 1916 Goldsmiths History Project.

22 year old Kathleen May Knott

16 year old William Denis Leberl

18 year old Winifred Phyllis Lockyer

66 year old James Alfred Longly

67 year old William Edward Mackenzie

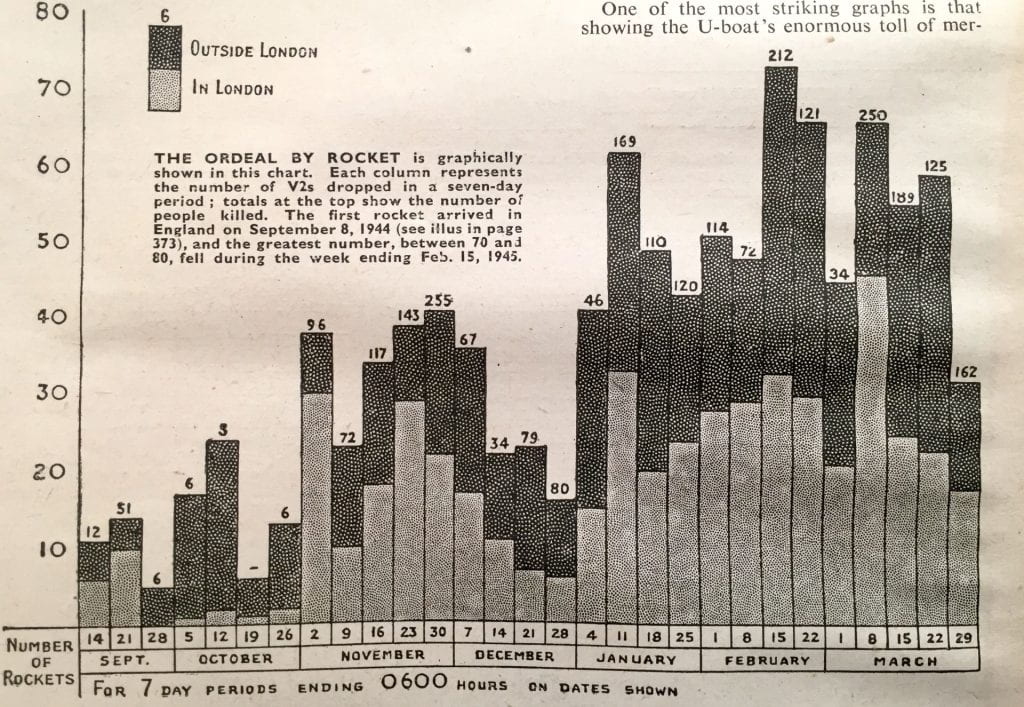

In 1945 War Illustrated published this graph analysis of the toll of V2 rocket fatalities and incidents in England between September 1944 and March 1945. The greatest number, between 70 and 80 fell in the week ending February 15th 1945.

60 year old Florence Ada Madden

48 year old Amy Matilda McCall

28 year old Alfred George Messenger

23 year old Gladys Vera Messenger

56 year old Charles Edwin Millett

38 year old Muriel Phyllis Millwood

9 year old Joan Pauline Millwood

View of the New Cross Road west of Deptford Town Hall at the junction with Laurie Grove circa 1916. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

41 year old Robert George Moore

52 year old Constance Dora Newell

77 year old Thomas Acton Noble

23 year old Joyce Kathleen Padbury

47 year old Frederick George Harris Pell

2 year old Pamela May Phillips

13 year old Hetty Letitia Josephine Plunkett

28 year old Angus Frederick Thomas Pugsley

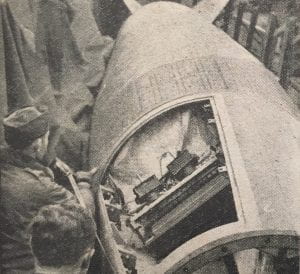

In 1945 the US Army captured an entire train carrying V2 rockets in Germany which had been loaded for distribution to mobile firing units. A feature in War Illustrated included images of engineers examining the weapon’s technology and components.

14 year old Ellen Elizabeth Roffe

19 year old Mary Lavender Rogers

62 year old George Phipps Routhorn

43 year old Freda Marjory Mabel Sherwood

28 year old Elsie Maud Shirley

42 year old Benjamin John Simmonds

15 year old Alan Charles Trevor Sinfield

31 year old Margaret Annie Snell

12 year old James William Snellgrove

Deptford Borough Council’s central library in Lewisham Way in the 1930s. It was constructed with a bequest from the Carnegie foundation. While still standing it is no longer a library service building. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

74 year old William Cuthbert Stephenson

66 year old Edward Frederick Strickland