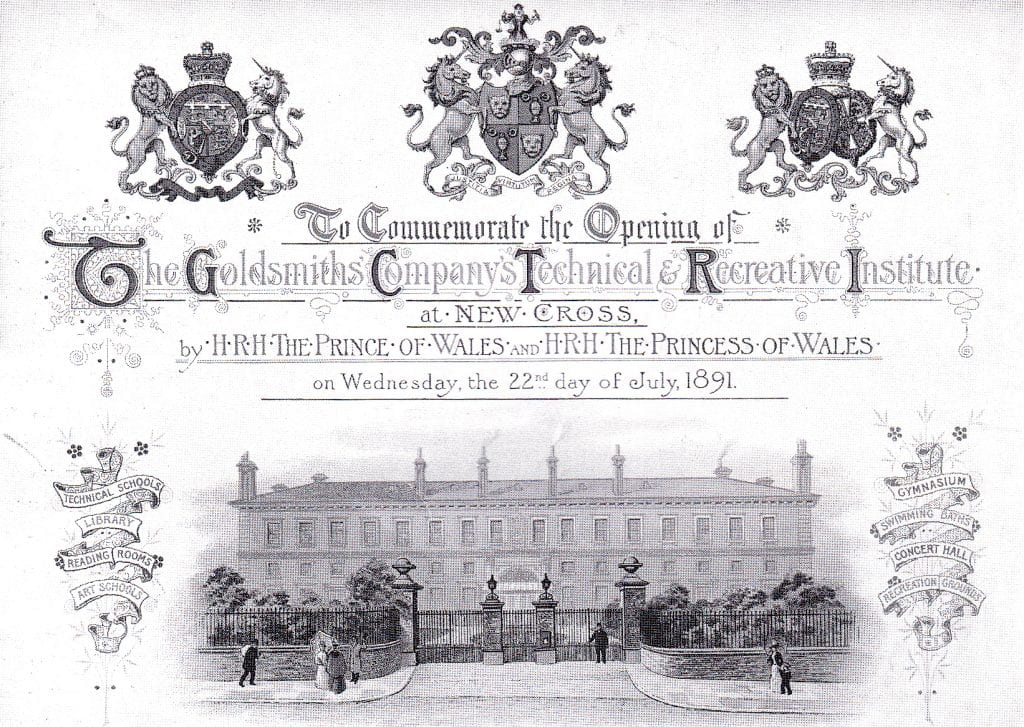

Commemorative card celebrating the opening of The Goldsmiths Company’s Technical and Recreative Institute in New Cross in 1891. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Goldsmiths as a university was conceptualised, developed and founded during the years 1903, 1904 and 1905.

In 1903 the Goldsmiths’ Company in the City of London realised that it could not continue philanthropically funding the Goldsmiths Technical and Recreative Institute- a hugely successful experiment in working class further education in New Cross serving thousands of people from all over London.

In 1904, the Company decided to offer the building and grounds to the University of London.

There had been three educational institutions on the site before London University took it over.

A boys’ private school, the Counter Hill Academy, was present between 1792 and 1838.

The Royal Naval School New Cross operated in the specially built main building from 1843 to 1889 which is largely still standing as the Richard Hoggart main building, though the distinctive neo-Wren chimneys were destroyed during WW2.

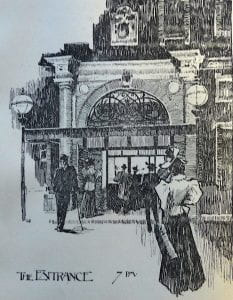

The front of the Goldsmiths’ Institute during the 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives and Special Collections Goldsmiths, University of London.

The Goldsmiths’ Company’s Technical and Recreative Institute bought the site and extended the buildings with a roof over the first quadrangle from 1891 until the decision to end its funding and activities by the autumn of 1904.

There is the famous letter from Sir Walter Prideaux written on the 29th February 1904: ‘My proposal is that the Goldsmiths’ Company shall present to the University of London the site and buildings known as the Goldsmiths’ Institute, at New Cross, with the fittings, apparatus, and equipment which they contain.’

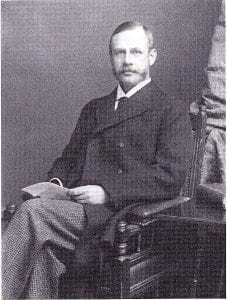

Sir Walter was the ‘clerk to the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths.’

Sir Walter Prideaux, Clerk to the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths, City of London. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

The University, then based in South Kensington, liked the idea, but had to do due diligence.

A report was put together by the recipient of Prideaux’s letter, the Principal of the University of London, Sir Arthur Rücker, for the Vice-Chancellor and members of the Senate.

This was presented for consideration on Wednesday 23rd March 1904.

A second report was produced for the Senate on the same day by Senate Chairman Sir Edward Busk who had carried out a site visit to the Institute in New Cross with Sir Arthur Rücker on Thursday 25th February 1904.

At this stage the Goldsmiths’ Company was informed that ‘the hearty thanks of the Senate be accorded […] for their generous and munificent gift.’

But no agreements had been signed nor had there been any conveyancing of land and property.

It is true that the Goldsmiths’ Company received a letter from Sir Arthur Rücker on 14th April 1904 ‘containing Copies of Resolutions passed by the Senate accepting the Company’s gift.’

Sir Arthur Rücker, Principal of the University of London. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

These negotiations and the acceptance of the offer were being reported in the Times and other newspapers.

Much more work needed to be done before Goldsmiths could be said to have properly been founded and created.

‘A Goldsmiths Institute Committee’ was set up to carry out investigations on how the University might use the site and the viability of any university institution in this part of South East London.

It was realised that there was a need for a non-denominational training college for teachers.

The University of London believed this would work if there could be guarantees from London and surrounding County Councils such as Kent, Middlesex, Surrey and Croydon Borough Council to pay for their training.

The momentous decision at a special meeting of the Senate of the University of London to establish a Training College for teachers combined with continuing the existing Art School and developing day and evening university courses in arts, sciences and engineering was made on the 29th June 1904.

This is the key date when it can be said Goldsmiths as a unique college of the University of London came into being.

And reports in local, regional and national newspapers confirm this.

On 30th June 1904 the London Evening Standard not only reported the latest news in the notorious Dreyfus case in France but also announced that the Senate of the University of London had decided to formally and ‘definitely accept the munificent offer’ from the Goldsmiths’ Company of the building and grounds.

Postcard of the Goldsmiths Technical and Recreative Institute in New Cross circa 1900 with its name emblazoned on the front of the building. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

The University further announced there would be a new training college opening in the autumn of 1905 for about 400 students and they would be following a two-year course to certificated qualification.

The University of London said it would continue the Institute’s Art School and ‘is prepared to carry on at New Cross the higher part of the work of a Polytechnic- such, for instance, as evening classes in preparation for Matriculation, and in Arts and Science up to the Pass degree standard.’

There would be day classes in preparation for the University’s Intermediate Examinations in Arts and Sciences in certain subjects.

The Goldsmiths’ Company also pledged £5,000 a year for five years to further support the project.

By this time approval had been given by the University’s Academic Council and the government’s Board of Education.

The question soon arose about the name of this new University of London institution.

In October it was suggested it should be called ‘The Goldsmiths’ College, New Cross.”

By 23rd November 1904 the Senate made a final decision on the title:

‘The title of the Institute [formerly known as the Goldsmiths’ Institute, New Cross] shall be “University of London, Goldsmiths’ College.”‘

These are the key dates when what is now Goldsmiths, University of London was truly founded and started- 29th June and 23rd November 1904.

There was, though, a hierarchy and status implied here.

In the original title, ‘Goldsmiths’ College’ came after ‘University of London’ and this highlighted the fact that Goldsmiths was not a standing federal College of the University of London like King’s College in the Strand, University College in Gower Street, or the future Imperial College in South Kensington and London School of Economics at Clare Market between Holborn and Covent Garden.

This would not happen until 86 years later in 1990.

And this is why Goldsmiths began to identify itself as ‘unique.’ There was no university body like it in Britain.

Some wags struggling to manage the place subsequently would quip it was unique because it was impossible.

The training department for student teachers was financed by the University of London via Board of Education grant, but depended on guarantees of paid studentships from five county councils.

The Art School and university evening classes would be financed by London County Council and the entire operation, certainly for the first five years depended on an annual subsidy from the City of London Goldsmiths’ Company of £5,000- the equivalent in February 2024 of just over half a million pounds per annum.

It was also decided that Goldsmiths’ College would be run by a specially constituted University of London ‘Delegacy’ which met for the first time on Friday 16th December 1904.

There was something rather patronising in the University of London deciding that its first teaching body south of the River Thames needed to be ‘delegated’ in terms of management- rather arm’s length and a little bit of holding the nose perhaps.

Goldsmiths’ College’s chief executives would not be known as the Vice-Chancellor which was the tradition in what might be described somewhat snobbishly as ‘real’ universities in the UK.

They would be called ‘Wardens’ after the title accorded to the Chiefs of the City of London’s Worshipful Goldsmiths’ Company.

Goldsmiths Hall in the City of London belonging to the Goldsmiths’ Worshipful Company which gave its name to the Goldsmiths’ Institute and College as well as providing large subsidies to support their financial stability. From an engraving by Thomas Shepherd (1792–1864) or alternatively Henry Albert Payne. Image: Public Domain.

Anyone unfamiliar with the history and culture of City of London Guilds could ordinarily associate a ‘Warden’ as being in charge of a prison or workhouse.

Like so much of the future history of Goldsmiths, the narrative between 1903 to 1905 was characterised by politics, argument and rancour.

There were newly established municipal authorities in London which were understandably piqued that the Goldsmiths’ Company neither considered gifting the Institute to them, nor directly consulted or involved them in any discussion about its future.

These were the local Deptford Borough Council which would be ensconced in its magnificent new Town Hall on the New Cross Road by 1905, and the London County Council which was to have a spectacular County Hall building constructed on the South Bank of the Thames facing the Westminster Houses of Parliament with an opening in 1922 and the final section completed in 1933.

Deptford Borough’s London County Councillor was none other than the social democratic Fabian Sidney Webb representing the ruling ‘Progressives’ group now in control of the LCC.

New Cross Road and the new Deptford Borough Council Town Hall completed in 1905 and around the same time University of London, Goldsmiths’ College was established. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Prideaux’s offer and what he hoped for…

The Goldsmiths’ Company had originated and funded out of its private resources the pioneering Technical and Recreative Institute at New Cross for 15 years. It was a model and inspiration for the concept of the Polytechnic providing advanced post-school technical education.

The national Balfour Education Act followed by the London Education Act of 1902 and channelling of public funding for education to the London County Council meant the Goldsmiths’ Institute now faced competition from LCC funded polytechnics.

It was ‘increasingly difficult for a voluntary institution like the Goldsmiths’ Institute […] to hold its own, and to keep pace with other Institutions financed by means of charitable and public funds.’

The Institute as it was then could not compete successfully with rivals ‘funded at public expense.’

He explained the site ‘comprises approximately seven acres, about three acres of which are covered with buildings and the four remaining acres have been hitherto used for the purposes of education. He described the site’s excellent railway and electric trams links and said: ‘The value of the site and buildings, after making a liberal allowance for depreciation of the latter, cannot be put at less than £100,000.’

The Bank of England’s inflation calculator puts that figure at today’s values (February 2024) the equivalent of £10,065,239.76.

The only condition they would attach to the gift is that ‘the property shall always be used for educational purposes, including research work.’

That codicil and covenant applies to the present day. To break it in theory means the site as it then was should revert to the Goldsmiths’ Company.

The Company hoped a future University body would include the teaching and practice of Metallurgy (especially that of precious metals), but that is something a future Goldsmiths University operation was never able or willing to do.

Frontage of Goldsmiths’ Hall, EC2 by Katie Chan. September 2013. CC BY-SA 3.0

He added: ‘…it is, I think, at least worth careful consideration whether the existing buildings at New Cross could not be made to serve the purpose of a University College for South London, to which teachers from that part of the Metropolis might be drafted.’

He intimated that he would recommend to his Worshipful Company that they provide an annual grant of £5,000 per year over five years to help the new College fend off any potential financial difficulties.

Prideaux had already given all the teachers and thousands of students at their Goldsmiths’ Technical and Recreative Institute notice of shutting down by September of 1904.

There was understandable grief, mourning and consternation among them about this prospect.

The London County Council had expected that such a gift would be coming their way and they may have known that Prideaux had been discussing this possibility with his colleagues in the Goldsmiths’ Company during 1903.

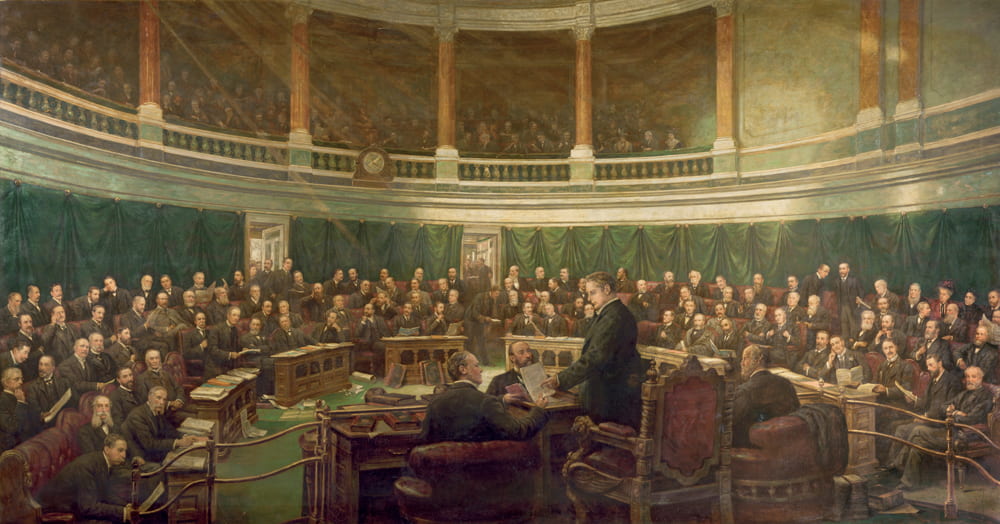

The First Meeting of the London County Council in the County Hall Spring Gardens, 1889 by Henry Jamyn Brooks. Image: Public Domain.

But he had changed his mind. There is some speculation this may have been because of the radical and progressive politics of the ruling group in the LCC.

The Rücker Report

Sir Arthur Rücker immediately identified the market and demand from Education Authorities in an around London requiring ‘education of a University character for Teachers, and that the number of persons to be provided for was greater than the existing Colleges could admit to their classes.’

Rücker was somebody who liked detail and the idea of County Councils stumping up £30 a year for each of their student teachers was key to the financial planning.

On the issue of accessibility Rücker also realised there was ‘no other site in South London except the immediate neighbourhood of Clapham Junction which has equal railway and tramcar facilities.’

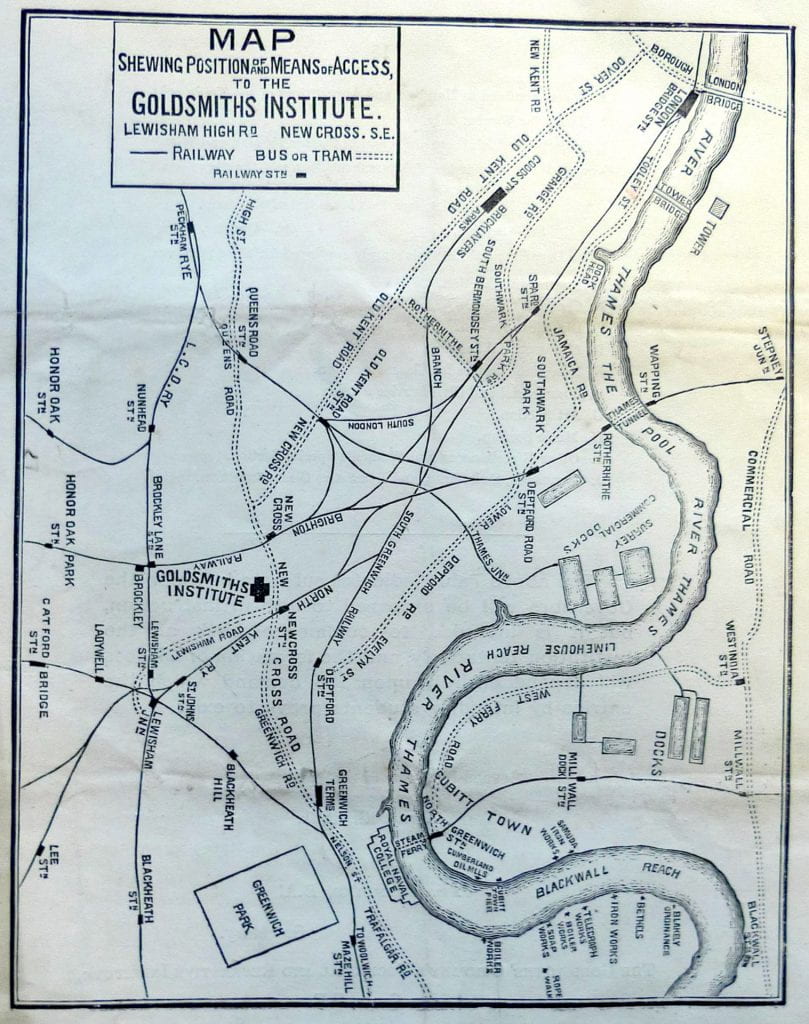

The Goldsmiths’ Institute transport connections 1904. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

He was not aware of any educational institution which had two railway stations either side of it, was served by London underground and overground services and between 9 and 10 every weekday morning thirty trains set down at one or other of the New Cross stations.

Like a perfect train spotter Rücker set out an impressive train timetable- only seven minutes to or from London Bridge. Ten minutes either way to Blackheath, Lewisham or St Johns.

The Metropolitan Line of what is now the London Underground connected New Cross to North London. Tramcars had a stop at the Institute’s entrance and this was a mere half an hour from the end of a wide nexus of routes extending to Charing Cross, Elephant and Castle, Hayes, Woolwich, Shoreditch and West Croydon.

Rücker highlighted the potential of the four and a half acres of recreational ground- ripe for further development as it was far away from housing, adjacent to a railway cutting, and the existing building ‘constitutes a very valuable asset’, most of it readily adaptable and ‘a considerable stock of apparatus.’

He envisaged university standard teaching of the subjects: Mathematics; Physics; Chemistry; Botany; Classics; English; French; German; Modern and Ancient History.

A coloured postcard of the Goldsmiths’ Institute in Lewisham Way circa 1900. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

He did the cost figures in detail. There would need to be an annual budget which included £7,400 for salaries, £3,000 for expenses, and rates, taxes, electricity, water and insurance of £1,300. In 2024 values, this would be: £744,827.74, £301,957.19, and £130,848.12 respectively.

He summarised with four recommendations:

‘(1) That the Goldsmiths’ Company declare their intention to close their Institute;

(2) That 200 students taking the full degree course at £30 a year be guaranteed;

(3) That the full payment be made in the first two years, though the number of guaranteed students will only be one-third and two-thirds of their final numbers in those two years;

(4) That a subvention [subsidy from Goldsmiths’ Company] of £5,000 a year be guaranteed.’

When the University of London duo of Busk and Rücker turned up from South Kensington for their conducted tour of the Institute and to see it in operation on 25th February 1904, staff and students could have been forgiven for thinking potential asset strippers had arrived to put a price on those things they thought had a future and those to be consigned to permanent closure.

The Busk Report

Sir Edward Busk’s report was much more detailed and reads like a verbal film camera roving through the Goldsmiths’ Institute campus:

‘The site, comprising about 7 acres, is bounded on the North-East by the Lewisham Road (where is the principal entrance), on the South-East by gardens at the back of houses in St Donatt’s Road, on the South-West by rough and rather hilly ground, and on the North-West by Dixon Road and Laurie Grove.

Cricket being played on the Goldsmiths’ Institute recreation ground during late 1890s. When Goldsmiths became a University of London College it would be renamed ‘the back field’ and then ‘the College Green.’ During Institute times the famous cricketer Dr W G Grace actually played on this field. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

The land on the South-West, which is bounded by the London Brighton and South Coast Railway, has not sufficient frontage to be really suitable for building and might possibly be repaired, if additional land were required either for metallurgical laboratories or the hostels for the residence of students.

The buildings, covering about 4 acres, were originally erected for a Royal Naval College and were taken over by the Goldsmiths’ Company in 1890. After some time spent in organisation the Institute was formally opened on 22nd July, 1891, and the actual work began on 1st October, 1891.

The main part of the building, shaped like the Greek letter Π, consists of a ground floor, a mezzanine floor and a first floor over it: but many of the rooms on the ground floor as so lofty as to include the mezzanine floor in their height. Each part of the building is 35 feet wide. Besides this building, there are many others on the ground floor level only, covering the ground between the main building and Dixon Road and Laurie Grove.

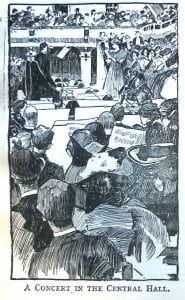

The top of the letter Π forms the front towards the Lewisham Road and immediately behind it is the great Concert Hall, capable of seating 1,700 people, with ample arrangements for ingress and egress [entrances and exits in architecture], and containing a valuable organ.

The Goldsmiths Institute’s Central concert hall (now called the Great Hall). In the 1890s it had painted frescoes and the balconies were plastered with the names of great composers. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Behind this organ is a large gymnasium with corridor and gallery (admirably suited for a laboratory): and the rest of the courtyard is occupied by tennis courts.

[The Π form would be closed into a quadrangle with the completion of the Blomfield Art School building in 1908. This would give rise to the students using this space as a popular meeting place between classes often described as ‘the quad’ from 1908.]

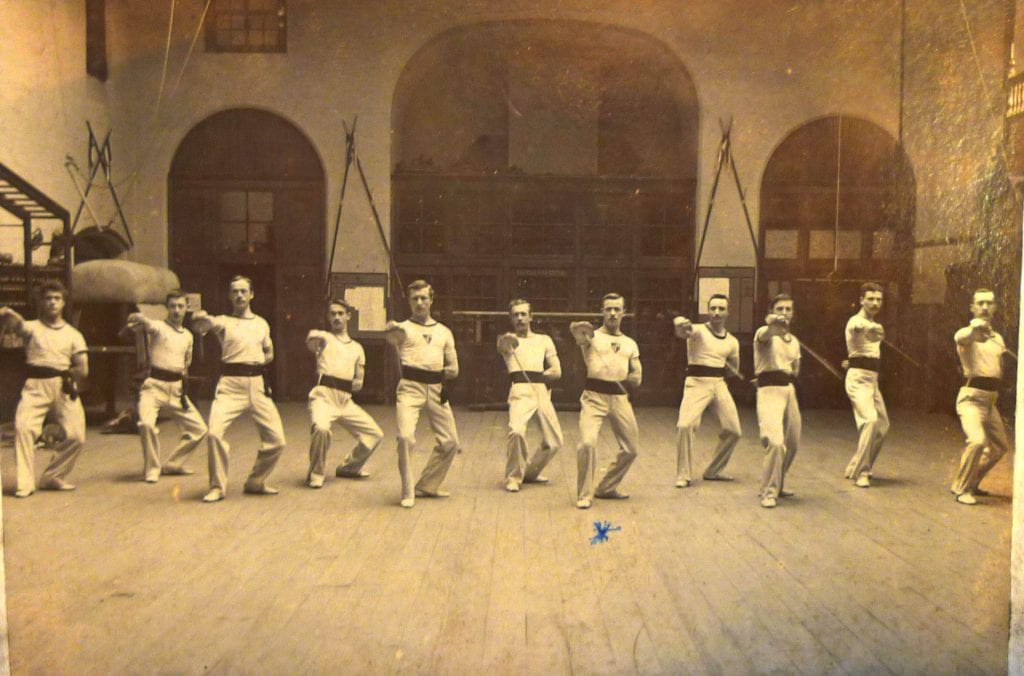

Goldsmiths Institute gymnasium. Circa 1900. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

The Secretary’s residence, the offices and bookstores, and the caretaker’s rooms occupy the ground and mezzanine floors of the front building. The top floor is occupied by the Library, Reading rooms and News room.

On the South-East side there are, on the ground floor, an Engineering Lecture room and four Class rooms, and also two cloak rooms, over which, on the mezzanine floor, are three small rooms. On the upper floor are a Museum, two Chemical Laboratories (accommodating together 60 students), a Lecture room, Preparation room, Chemical Stores room, and a Balance room.

Illustration of a chemistry student at the Goldsmiths Institute 1896-7. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections

There is also a Woman’s Social room.

Over the Museum and Lecture room are Photographic Studios with dark room and enlarging room.

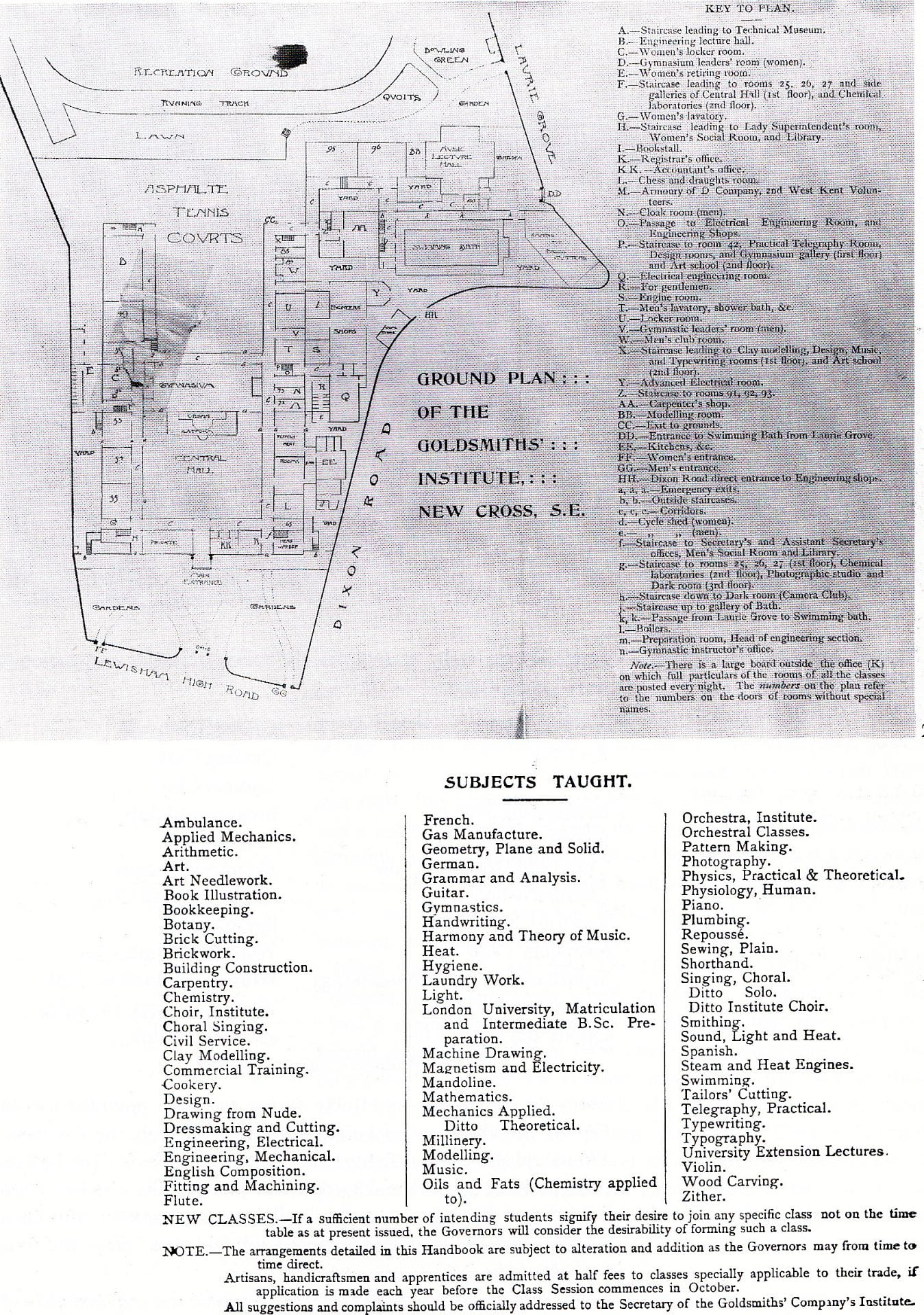

Ground Plan for the Goldsmiths’ Institute and subjects taught. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

In the North-East wing there are, on the ground floor, Refreshment rooms (occupying the old dining hall) and rooms for bicycles, lockers, office stores and lavatories. These rooms are not well lighted, owing to the buildings between this wing and Dixon Road on the one side and the Concert Hall and Gymnasium on the other.

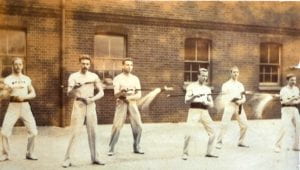

En Garde! The Goldsmiths’ Institute fencing team in the gymnasium circa late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Almost all these rooms rise into the mezzanine floor, but there are on that floor three Modelling rooms, a corridor used for designing, two rooms used for upholstery, and a Members’ room. The upper floor of this wing comprises Modelling rooms, a Life School, a draped Life School and Drawing room, advanced Art room, an elementary Art room, and a Masters’ room. There is also a Men’s Social room.

Goldsmiths’ Institute Advanced Art Room circa late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

The other buildings comprise (besides kitchen, scullery &c.) Mechanical Laboratory, Engine room (26-house power) for driving shafting and for pumping, two Engineers’ shops and dynamo room.

Goldsmiths Institute athletes practicing what appears to be flag-waving or standard juggling drill late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections

A Carpenter’s shop with a large room over it, an Electrical Laboratory (accommodating 40 students) and Class room, two Clay Modelling rooms, a Lecture Hall (formerly the Chapel) with a most remarkable echo rendering it quite unfit for lectures.

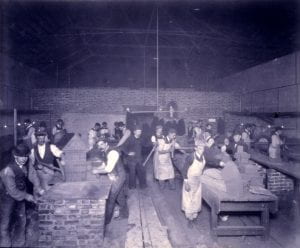

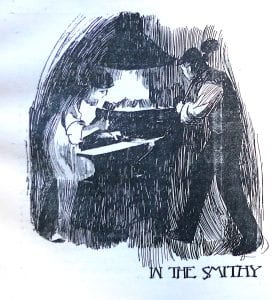

A shop for plumbing, metal fitting and electric wiring, a smithy, and a brick-cutting shop.

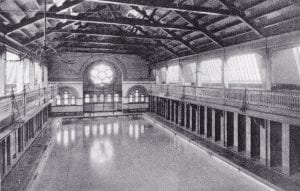

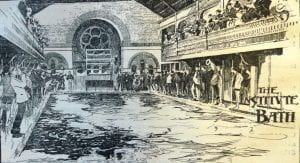

There are also a large Swimming Bath and an Electric Light station containing three Willan’s engines and an accumulator room to be used in case of emergency.

Goldsmiths’ Institute swimming bath with changing rooms. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

At the back of all these buildings, on the south west, is the Recreation ground.

The Institute consists of a Recreative and Social side and of an Educational side.

The former is for young persons of both sexes between 16 and 30 years of age primarily, though older persons may be elected if there are vacancies. Members use the lending and reference library, the reading and writing rooms, the gymnasium, the swimming bath, the social and club rooms with billiard tables, the cinder running track, bowls green, and recreation grounds.

Goldsmiths’ Institute gymnastic team performing in the New Cross main building gymnasium late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

They have also free entrance to Organ Recitals, and admission to Concerts at reduced prices. Clubs and Societies have been formed for Art, Literature, French, Shorthand, Chemistry, Engineering, Photography, Chess and Draughts, Football, Cricket, Rowing, Boxing, Cycling, Lawn Tennis, Quoits and Bowls, Swimming, and Volunteering. There is also a Choir and Orchestra, and a Mandoline Band.

Goldsmiths’ Institute sports team at New Cross late 1890s bearing equipment for all kinds of sports from boxing to fencing. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

The Educational side comprises a Day Department and an Evening Department.

During the day the School of Art is open, and elementary, advanced, and life classes are held under the direction of Mr Frederick Marriott, assisted by Mr W. Amor Fenn for Design and Mr Percy Buckman for the Life.

Life modelling for Goldsmiths’ Institute students in the late 1890s at New Cross. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archive.

There are also day Music Classes under Charles Joseph Frost, Mus. Doc. (Cantab.) and his assistants in Harmony, Counterpoint, Theory of Music, Singing, Playing on the Pianoforte, Violin, Violoncello, Flute, Mandoline, Guitar, &c. Besides these there are day Civil Service classes for female sorters, telegraph learners, women clerks and girl clerks.

The Evening Department of the Educational side is divided into 11 Sections as follows:-

Section A.- Engineering (Mechanical and Building) under W. J. Lineham, M.I.C.E., M.I.M.E., M.I.E.E. The arrangements are for three years’ courses of lectures, with practice in the workshops, in both branches.

Brickwork class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross during 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Section B.- Chemistry and Photography under Arthur Lapworth, D.Sc. (Lond), F.I.C. There are courses of two years each in Inorganic and Organic Chemistry, and there is in each branch a third year (or Honours) course.

Section C.- Electrical Engineering under Douglas Neale, A.M.I.E.E.

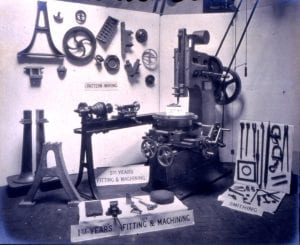

Fitting, machining and pattern-making workshop at the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

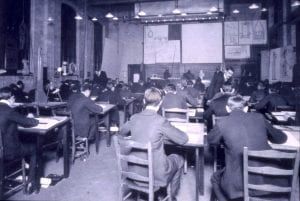

Section D.- Mathematics and Physics under G.C. Turner, B.Sc. In Pure Mathematics and Mechanics instruction is given in various stages, and also expressly for Matriculation and Intermediate Science, and there are two years’ courses for the B.Sc. The course of instruction in Physics lasts three years, and that in Electricity and Magnetism two years.

Dynamo testing class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross during late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Section E.- Civil Service Preparation under Robert Smith. In addition to the subjects of the Day Classes under this head there are subjects for Second Division, L.C.C. and School Board Clerkships, for Excise and Customs, for Boy Copyists, Male Telegraph Learners, &c.

Mechanical drawing class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute, New Cross during the late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Section F.- Commercial. In this section are taught English, French, German, Spanish, Arithmetic, Book-keeping, Commercial Geography, Handwriting, Shorthand (Pitman’s and Script), and Typewriting.

Electrical laboratory at the Goldsmiths’ Institute, New Cross, late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Section G.- School of Art under Frederick Marriott, assisted by W. Amor Fenn (Design), A. Drury, A.R.A. and A.G. Walker (Modelling), P. Buckman (Life) G.C. Jackson (Wood Carving), Miss M. Smyth (Art Needlework), and others. There is also metal work and enamelling, and design students can execute their designs in iron, brass or copper, in the smithy.

Cookery class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross during late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Section H.- Music under Charles J. Frost, Mus.Doc. (Cantab.), F.R.C.O., Professor G.S.M. &c. The subjects are those mentioned under this head in the Day Department.

Dressmaking class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Section I- Women’s Special Classes, comprising Ambulance, Practical Cookery, Laundry Work, Dressmaking and plain needlework, Millinery, Upholstery and Carpentry.

Dressmaking exhibition in the Central Hall (now Great Hall) of the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross circa 1898. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Section J.- Gymnastic and Recreative Classes including Swimming lessons open to members only.

Laundry class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross, late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Section K.- Miscellaneous not otherwise classified:-

London University Examinations (Matriculation and B.Sc.); Latin; Botany, elementary and advanced; Hygiene, elementary and advanced; Human Physiology, elementary and advanced; Plumbers’ Work, two years’ course; and Tailors’ cutting.

Carpentry class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross, late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

There are in the aggregate between 7,000 and 9,000 class entries in the years; but it is not possible to say how many students, as in some sections such students take several classes, while in others (such as Fine Art) each class entry represents a separate student.

Smithing class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross during late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

The last account available is that for 1902-03 and the following is a summary of it:-

Receipts. £ s d

Institute Membership Fees: 595 3 11

Students’ Class Fees: 3,331 12 4

Government Grant: 1,984 0 0

Annual Endowment from the Goldsmiths’ Company 5,000 0 0

Grant in aid from the Goldsmiths’ Company 4,500 0 0

Concerts and Entertainments 544 0 0

Sundry Receipts 399 16 3

Total: £16,354 12 6′

Busk set out an expenditure table totalling £14,685 1s 11d.

He noted that the Students’ Fees and the Government Grant together are almost enough to pay the Teachers’ salaries. The most expensive part of the work was incurred with the social side of the Institute’s work (about £3,000 per year) and the recreative side of the Institute was also responsible for the heavy rates and taxes.

Plumbing class at the Goldsmiths’ Institute late 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives. Plumbing remained a core engineering subject at Goldsmiths for another 15 years.

He concluded:

‘The buildings appear to be substantial and sound, and not to require structural repair; but they do require extensive cleaning and painting, and the cost of these decorative repairs and of the alterations that will be necessary, if the University accepts the offer of the Goldsmiths’ Company, cannot in my opinion be estimated at less than £5,000.

The offer is so valuable and the necessity of providing (if possible) a University College in the South East of London is so great that I hope the University may see its way to acceptance. As the University could not keep open all the sites and departments, it might be well for the Goldsmiths Company to close the Institute and hand it over to the University, which would re-0pen it as a University College at the end of the year, after they had done the repairs and made the necessary alterations, the cost of which could be defrayed out of this first year’s grant of £5,000 from the Goldsmiths’ Company.’

Exhibition of the students’ engineering work at the Goldsmiths’ Institute circa 1898. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives.

Rücker added: ‘Accepting the Goldsmiths’ Company’s estimate that the Recreative side of the Institution costs £3,000 a year, the cost of the Educational Institution amounts to £11,685, which is in close accord with my estimate of the costs of a University College of the type I considered, viz., £11,700.’

The Political Row over the Institute’s Closure

To say there was a political row over the Institute’s closure is an understatement.

In fact it turned into something of a public scandal.

Deptford’s Progressive Group London County Councillor Sidney Webb was appalled.

Beatrice and Sidney Webb- who was Deptford’s London County Councillor. Image from London School of Economics archives circa 1896.

The Mayor of Deptford Borough Council was equally outraged.

The Goldsmiths’ Company reported ‘the opposition by various persons and Bodies who were hostile to the transaction’ in their minutes of the time. It was even noted that ‘at one time the position was one of considerable anxiety and even peril; but that, happily, the attempts to frustrate the arrangement had been defeated.’

In July 1904 The Morning Leader newspaper said the Goldsmiths’ Company had ‘abandoned’ what had been ‘the splendid centre of polytechnic and secondary education.’

Councillors ‘strongly criticised the action of the company in washing their hands of the Institute so unexpectedly, and so creating a big gap in secondary education south of the river.’

This pen and ink illustration by a Goldsmiths Institute art student in 1896 captures the buzz and excitement of members at the entrance around 7 pm making learning a social virtue. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

There was much indignation that the University of London wanted the London County Council to carry on the polytechnic evening classes and this anger had only been assuaged by a promise from the Goldsmiths’ Company to provide another £5,000 to keep these classes going for another year.

There had been ‘keen regret’ felt by all Councillors at ‘the abandonment of the Institute by the Company, whom everybody had expected to carry it on in perpetuity.’

The County Council actually passed what amounted to a vote of censure of 65 to 35 against the Goldsmiths’ Company.

There were public petitions campaigning against what was going on.

There were demands for compensation for those teachers and staff losing their jobs and hoping the Goldsmiths’ Company could keep the Institute open for a further year before the University took over in September 1905.

The Institute’s Secretary, Oxford educated barrister J.S. Redmayne, led a staff cohort of around 150 lecturers, 40 of whom were full-time.

In March 1904, the Kentish Mercury newspaper condemned the closure as ‘a bolt out from the blue […] in the opinion of many, the interests of the district would have been more satisfactorily considered had the Company made approaches to the County Council’s Education Committee with a view to handing over the Institution to them […] If the University should take over the Institute for its own purposes it will be goodbye to the Art School- the best in London- and goodbye to the great engineering classes (with a thousand students) […] unequalled by any of the Polytechnics.’

The Goldsmiths’ Institute had its own Smithy and the metal work was a symbol of the culture of life-learning forging a better future for the students taking day and night classes. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

In April Edith Beattie was the Honorary Secretary of the Institute’s Women’s Social Room Committee and wrote to the editor of the Kentish Mercury:

‘Sir,- On behalf of the members and students of the Goldsmiths’ Institute I have been asked to write to you, in the hope that we may, through the medium of your valuable paper, arouse public sympathy with us. There are, as your readers well know, 10,000 of us, members and students. Ours is the only institution of the kind in S.E. London. We hold splendid records for our work and for our play. Our art-school and gymnasium are recognised as unequalled in London. Nowhere else do such excellent commercial and mechanical classes exist, &c,. &c. Yet these good things shall come to nought after September, if the London University be installed in their stead. We realise that university teaching may be welcomed to this district by a small percentage of the population; yet by far the greater number of folk will desire the continuation of these valuable technical and scientific classes that are now being carried on so successfully, and for which the building is so magnificently equipped. Therefore we venture to hope that the voice of public opinion will be raised on our behalf to prevent the sacrifice of the very many for the good of the very few, and that the new governing body may be prevailed upon to recognise the needs of those thousands who look to the Institute for secondary education and for recreation facilities. On behalf of the members and students, – I am, &c Edith Beattie, Hon. Secretary Women’s Social Room Committee G.C.T.R.I.’

A sketch of the Women’s Social Room at the Goldsmiths’ Institute in New Cross 1896. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

The Goldsmiths’ Technical and Recreative Institute had planted deep roots of loyalty and respect into the wider community of South London.

When its stated mission had been ‘the promotion of individual skill, general knowledge, health and well being of young men and women belonging to the industrial, working and poorer classes’ it is easy to understand why so many people came to rely on it, and have a deep affection for how it had given them social, educational and professional opportunities they would not otherwise have had.

‘A Club Night’ in the Goldsmiths’ Institute swimming bath/pool circa 1896. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

These roots extended physically beyond the New Cross campus, for the Institute had a satellite building in the heart of old Deptford- The Sayes Court annexe in the grounds of what had been the 17th century writer John Evelyn’s home.

On 9th December 1896, a future Liberal government cabinet minister Augustine Birrell distributed 614 prizes to young people for their achievements in courses and qualifications from the government’s Science and Art Department, the Royal Society of Arts, and the City and Guilds of London.

The Sayes Court annexe of the Goldsmiths’ Institute providing teaching and learning facilities for Institute courses in the centre of old Deptford. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

It was possible to study for a University of London pass degree in science by attending night classes. The Goldsmiths’ Company also provided £5 and £10 scholarships to boys and girls attending elementary schools in Greenwich.

The Institute’s buildings and grounds pulsated energy, learning and fun day and night and the social side blazed Art Nouveau elegance after 7 p.m so wonderfully evidenced by the hand-drawn illustrations made by the art students for a special handbook printed for 1896-7.

Illustration by a Goldsmiths Institute Art School student capturing the atmosphere of a live concert in the Central Hall- capable at the time of accommodating well over 1,000 spectators. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections

The clubs and societies with affordable annual subscriptions of 7 shillings for men and 5 shillings for women created a culture of aspiration, intellectual, scientific and artistic inquiry, and sporting achievement for people of all backgrounds.

This could not be replaced by a university primarily funnelling pedagogical teacher training and post-school education for 18 to 21 year-olds.

This was why the Woolwich Herald reported Friday 6th May 1904:

‘Mr. H. W. Manley presided on Friday at a mass meeting of members of the Goldsmiths’ Institute, New Cross. It was proposed to present a petition to the Chancellor and Senate of the University of London to the effect that the signatories viewed with considerable alarm the high probability of 7,000 students and 1,200 social members of the Institute being left without suitable accommodation. This was agreed to with practical unanimity, as was also the text of a petition to the Goldsmiths’ Company, asking that body to assist the University to continue the work of the Institute on its present lines until the polytechnic and social needs of the district could be permanently met.’

The successful Goldsmiths’ Institute Journal was a testament to the Institute’s popularity and patronage by thousands of students and members. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Two items under the heading ‘Institute Gossip’ for the Journal’s June 4th 1892 edition reflect the liveliness and richness of the place. There’s a letter from the Lyceum Theatre from no less than the greatest actress of the time, Ellen Terry:

‘Dear Sir,

I am exceedingly sorry to say that I find I must give up taking the Elocution examination which I had agreed to do for you, on June 28th. I am sure you will excuse me, when I tell you that my health is the chief reason for this. It is so uncertain of late that any engagement I enter into, beyond my usual work of an evening, is nearly always given up at the last moment, and rather than disappoint and necessarily inconvenience you at a later date, I feel it is best to ask you to excuse me now.

I am sure you will understand how willingly, and with what real pleasure I would do it, if I felt equal to it, but as the warm weather advances, I feel I dare not promise myself for any extra work, which I feel so uncertain as to being able to perform.

Believe me, Dear Sir, with many regrets to remain,

Yours truly

(Signed), ELLEN TERRY.’

The Institute clearly encouraged sign and fresco painting. Might it be said there were Victorian ‘Banksies’ at work in New Cross at this time?

‘Talking about adorning the walls of the Social Rooms one cannot fail to remark the picturesque display of painted notice boards which are gradually covering the walls of the two Social Rooms. The art of Sign Painting is evidently flourishing at the Goldsmiths’ Institute, if one may judge by the boards in question, and there is a considerable amount of rivalry amongst the various Clubs to secure the services of artists of repute amongst us for the adornment of the aforesaid boards. Miss Ingle and Miss Delarue are conspicuously successful in this branch of art. The Literary Society’s Board in the Women’s Social Room is a distinctly successful study of Still Life, and we were pleased to notice how beautifully the Institute Journal has been painted in the group of books which forms its decoration. We are informed that the fair artist went down to the boat-house, at Greenwich, and made the necessary studies of oars and rudder from real life. ‘

A sketch by an Art School student of one of the refreshment rooms (which were Temperance) at the Goldsmiths’ Institute circa 1896. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

In April 1904 J. E. G. de Montmorency wrote an article for the Kentish Mercury setting out a dream for ‘an immense University College in South London […] fed by all the great Secondary and Higher Primary schools of this area, with its population of one and three quarter million.’

He had hopes for a great library unrivalled in South London so that:

‘the South London University College would do all for South London that is done for North London by University College in Gower Street […] South London has its Cathedral. In the name of all that is reasonable and wise let it also have its University.’

In the end nobody got all that they wanted.

The Goldsmiths’ Company did fund the transitional year between October 1904 and September 1905 to enable the University of London to change the Institute into ‘Goldsmiths’ College.’

- Life modelling at the Institute. Sketched by Art School student 1896.

- Singing lesson at the Institute. Sketched by Art School student 1896.

Most of the Institute’s teachers lost their jobs, but there was, for the time, a generous redundancy scheme for which the Goldsmiths’ Company set aside £6,709.

The Company also provided an additional £5,000 grant to fund the evening Polytechnic university standard classes between 1905 and 1906. This certainly went some way to placating the London County Council which had bitterly complained they had been given no time to adjust their budget for polytechnic teaching in that year.

Most of what Edith Beattie wanted- the much-loved recreational and secondary educational sides serving so many thousands of young people in the South London community would disappear.

No more elocution, cookery, shorthand, Repoussé and Zither classes- directly catering for those vocational skills serving the employment market.

The engineering, building and technical teaching would be sustained up to a point; certainly not expanded or developed.

Eventually they could flee to a home of their own in a South East London Technical College a mile or two down Lewisham Way some twenty years later.

And certainly no University College London à la Gower Street in New Cross.

One hundred years later if Goldsmiths could ever really be considered the Oxbridge of the Arts, an alumnus making it big in the music industry would quip it was more screeching tyres than dreaming towers.

It might be considered as some historical irony that those public authorities making the most critical noises about Goldsmiths’ evolution from Institute to University of London teacher training department with a small Art School add-on, would not survive the 20th Century.

Deptford Borough Council and the London County Council would be liquidated in local and regional government reforms of 1963- becoming Lewisham Council and the Greater London Council ‘GLC’ respectively.

Goldsmiths, University of London Special Collections has this very rare badge worn by an athlete representing the Goldsmiths’ Technical and Recreative Institute 1891 to 1904.

-o-

Many thanks to the archivists of the Goldsmiths’ Company, City of London, to the staff of Special Collections and Archives at Goldmiiths, University of London including Dr Alexander Du Toit, and staff alumni Pat Loughrey, Ian Pleace and Lesley Ruthven.

The Goldsmiths History Project contributes to the research and writing of the forthcoming That’s So Goldsmiths: A History of Goldsmiths, University of London by Professor Tim Crook.