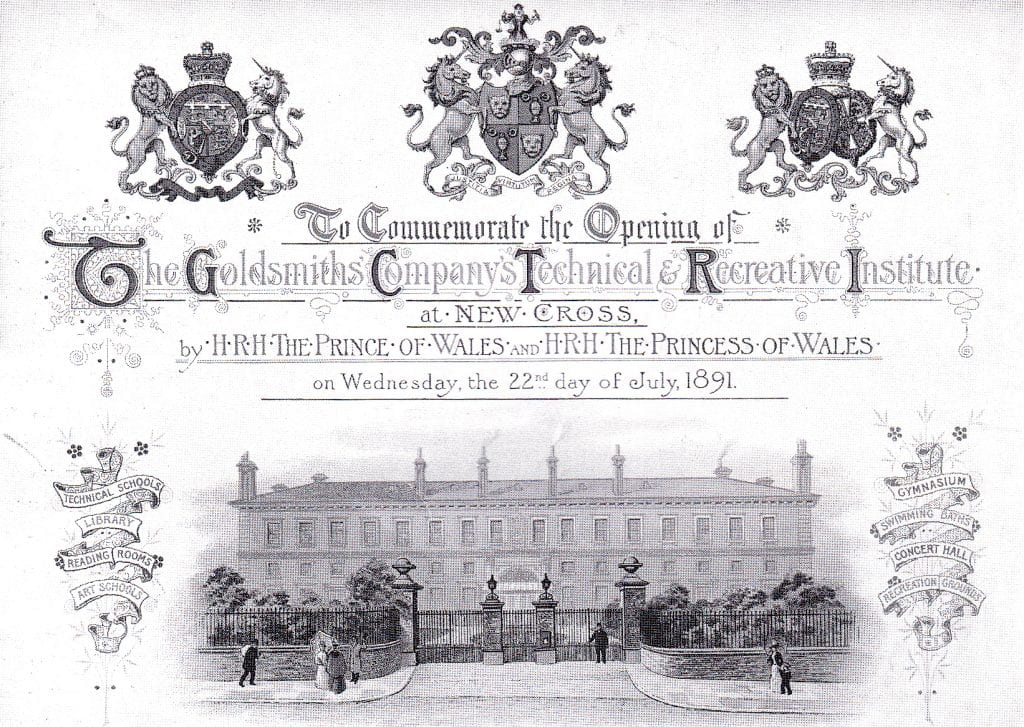

Commemorative card celebrating the opening of The Goldsmiths Company’s Technical and Recreative Institute in New Cross in 1891. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Goldsmiths as a university was conceptualised, developed and founded during the years 1903, 1904 and 1905.

In 1903 the Goldsmiths’ Company in the City of London realised that it could not continue philanthropically funding the Goldsmiths Technical and Recreative Institute- a hugely successful experiment in working class further education in New Cross serving thousands of people from all over London.

In 1904, the Company decided to offer the building and grounds to the University of London.

There had been three educational institutions on the site before London University took it over.

A boys’ private school, the Counter Hill Academy, was present between 1792 and 1838.

The Royal Naval School New Cross operated in the specially built main building from 1843 to 1889 which is largely still standing as the Richard Hoggart main building, though the distinctive neo-Wren chimneys were destroyed during WW2.

The front of the Goldsmiths’ Institute during the 1890s. Image: Goldsmiths’ Company archives and Special Collections Goldsmiths, University of London.

The Goldsmiths’ Company’s Technical and Recreative Institute bought the site and extended the buildings with a roof over the first quadrangle from 1891 until the decision to end its funding and activities by the autumn of 1904.

There is the famous letter from Sir Walter Prideaux written on the 29th February 1904: ‘My proposal is that the Goldsmiths’ Company shall present to the University of London the site and buildings known as the Goldsmiths’ Institute, at New Cross, with the fittings, apparatus, and equipment which they contain.’