Goldsmiths, University of London Richard Hoggart main building entrance in 2023 with a jet plane flying overhead. Image: by Tim Crook for the Goldsmiths History Project.

Armistice Day- the eleventh day of the eleventh month symbolises the UK’s immeasurable losses to armed conflict in the Great War of 1914 to 1918. It is then followed by Remembrance Sunday.

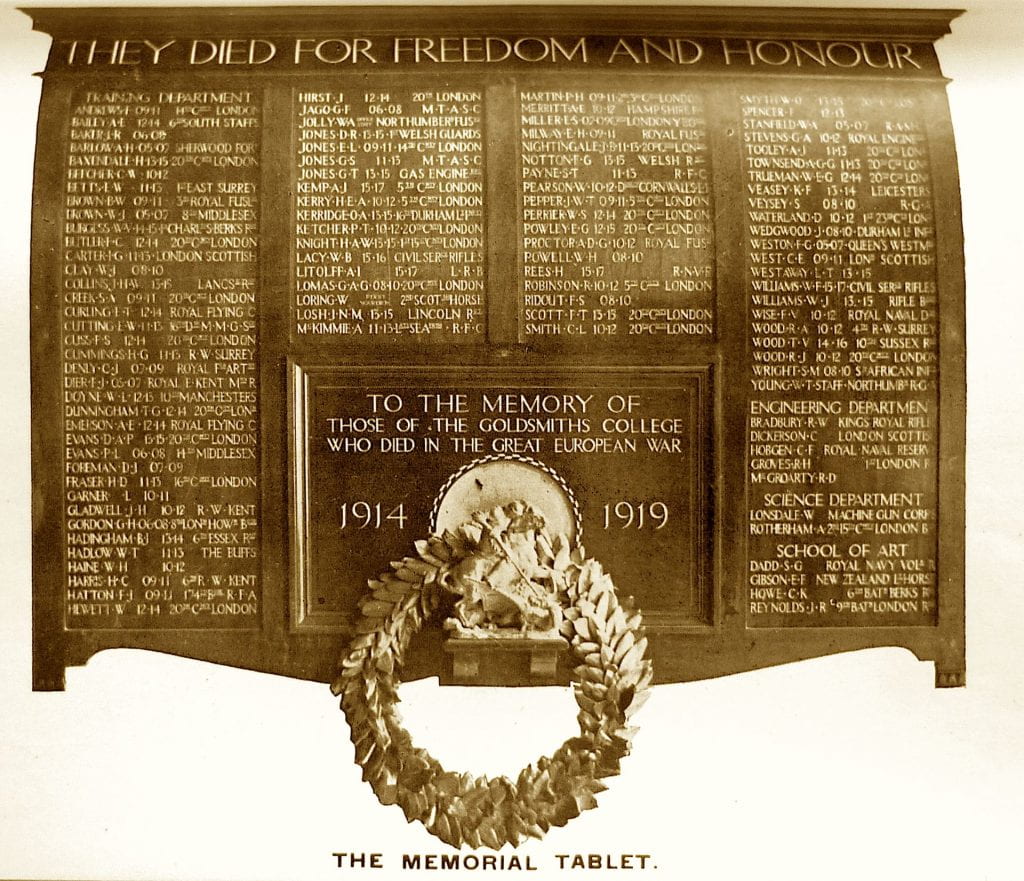

The memory of those who died in war is one of the first displays seen when walking through the Goldsmiths entrance. It is set out in the polished and carved brown oak panel in the alcove to the left.

It is very tactile in the sense you can touch the surface with your fingertips and outline the names commemorated for ‘They Died For Freedom And Honour.’

When the sun streams in through the windows, light can shine on the group of individuals where rank and service is identified with the names of people who had mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters and more often than not young children; sometimes infants who would grow up without any memory of a father’s voice, smile, touch and loving eyes.

Image: Tim Crook for the Goldsmiths History Project.

This is a panel for the twentieth century which would see more terrible manifestations of ‘total war’ and the losses of the Second World War of 1939 to 1945 and indeed deaths of all kinds in so many other armed conflicts are now very much part of the Remembrance ritual.

The panel only has one reference to the Second World War and the history of Goldsmiths and its local community for these years is a remarkable story of art, heroism, tragedy and resilience.

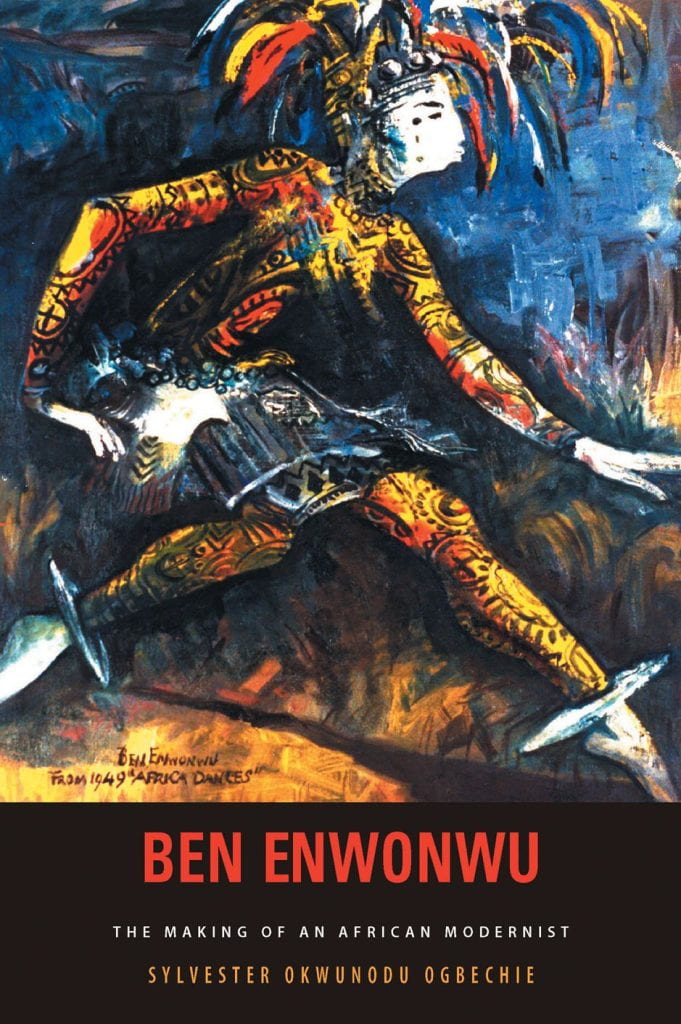

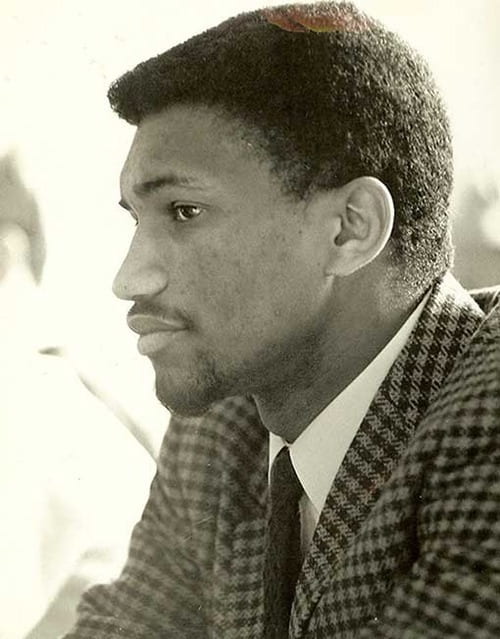

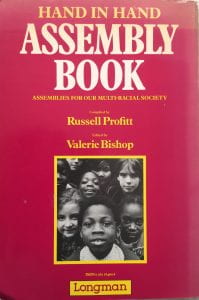

Africa’s pioneering and revered modernist sculptor and artist Ben Enwonwu painted and carved in the Art School’s Blomfield block on a Shell Petroleum scholarship in 1944 and survived a deadly V1 blast in the middle of the backfield killing two RAF men operating barrage balloons and the V2 disaster at nearby Woolworths in the New Cross Road.

Many of the 168 victims killed were laid out for identification in the premises of Pearces Signs in St James’s and quite possibly the Goldsmiths’ College swimming pool building which had been converted into a mass casualty mortuary by Deptford Borough Council’s First Aid services.

The founder of the League of Coloured Peoples, Dr Harold Moody, would have taken part in the rescue and saving lives operation. He was in the network of emergency medics drawn from local GP surgeries and hospitals.

121 people had been seriously injured and needed treatment among the rubble.

The wreckage area covered a wide expanse of the junction between St James’s, New Cross and Goodwood Roads. Woolworths had been obliterated along with half of the neighbouring Coop store.

George Arthur Roberts BEM MSM (1891-1970) Great War veteran, Leading Fireman WW2 and educator. Image: By Figures CC BY-SA 4.0

Heroism was also in abundance throughout this period on the part of founder member of the League of Coloured Peoples and decorated Trinidad born Great War veteran George Arthur Roberts.

Between 1939 and 1945 he was a leading fireman at New Cross fire station and attended four bombing attacks and fires at Goldsmiths which devastated the building and left the swimming pool turned mortuary a roofless and blackened shell in May 1945.

Crews and appliances from his New Cross station would have been the first on the scene of the Woolworths disaster on Saturday 25th November 1944.

George would be awarded an MBE recognising his pioneering discussion and education groups in the fire service, and his magnificent portrait would be painted in 1941 by fellow firefighter Norman Hepple, an artist educated at Goldsmiths School of Art.

Staff and students at Goldsmiths do not need to be reminded about all the political contestations surrounding the ritual and the struggle to challenge and overcome the invisibility of heroic contributions and losses from communities previously ignored, disrespected and unrepresented.

History is, of course, an academic discipline engaged with remembering. Historians devote themselves to visiting the ghosts of the past conjured in documents, objects and buildings.

This posting seeks to take you on a journey to meet some of those ghosts and ask questions about the documents, objects and buildings. What do they mean? And what do they represent of the people who were part of Goldsmiths in the past?

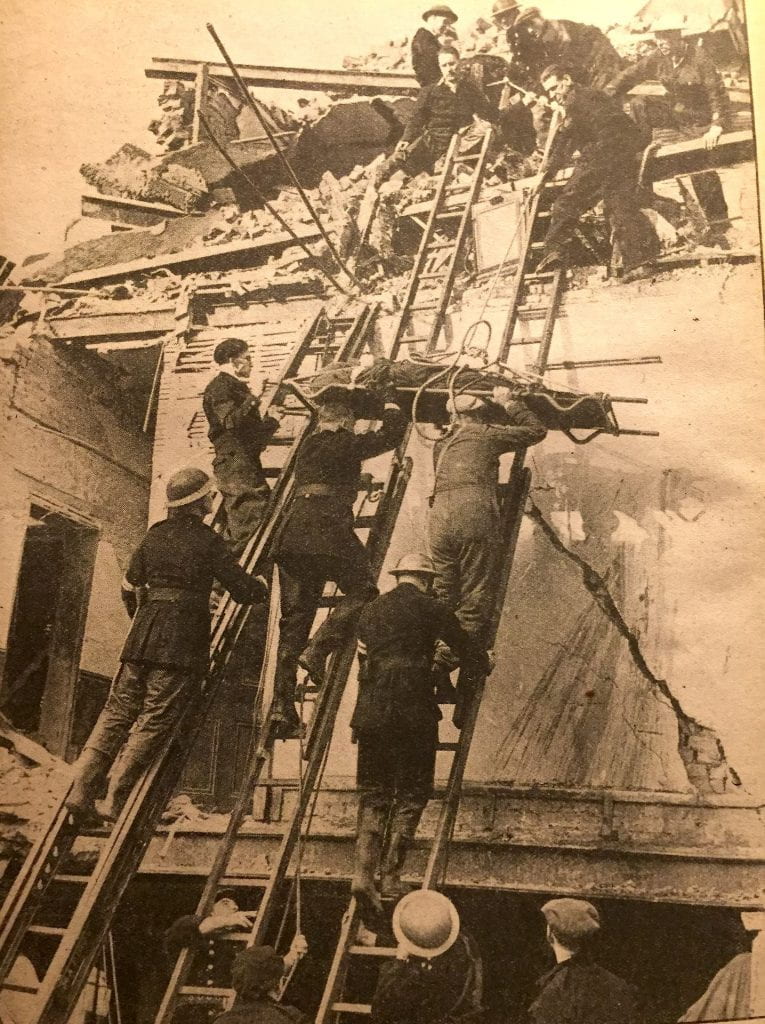

National Fire Service teams rescuing a casualty from a German V2 rocket attack in London during the autumn of 1944. Image: War Illustrated Number 197, page 509, January 5th 1945

Loss and mourning and survival are explored through the theme of aerial view. What can be seen from the sky and looking up at the sky and sadly what sometimes falls from it.

The featured image is looking up from the entrance of the Richard Hoggart main building where there is a passenger jet flying overhead between 2,000 to 4,000 feet from the ground.

In the early 1920s, planes flying over Goldsmiths were a rare occurrence though German Zeppelins did and they dropped bombs in 1915.

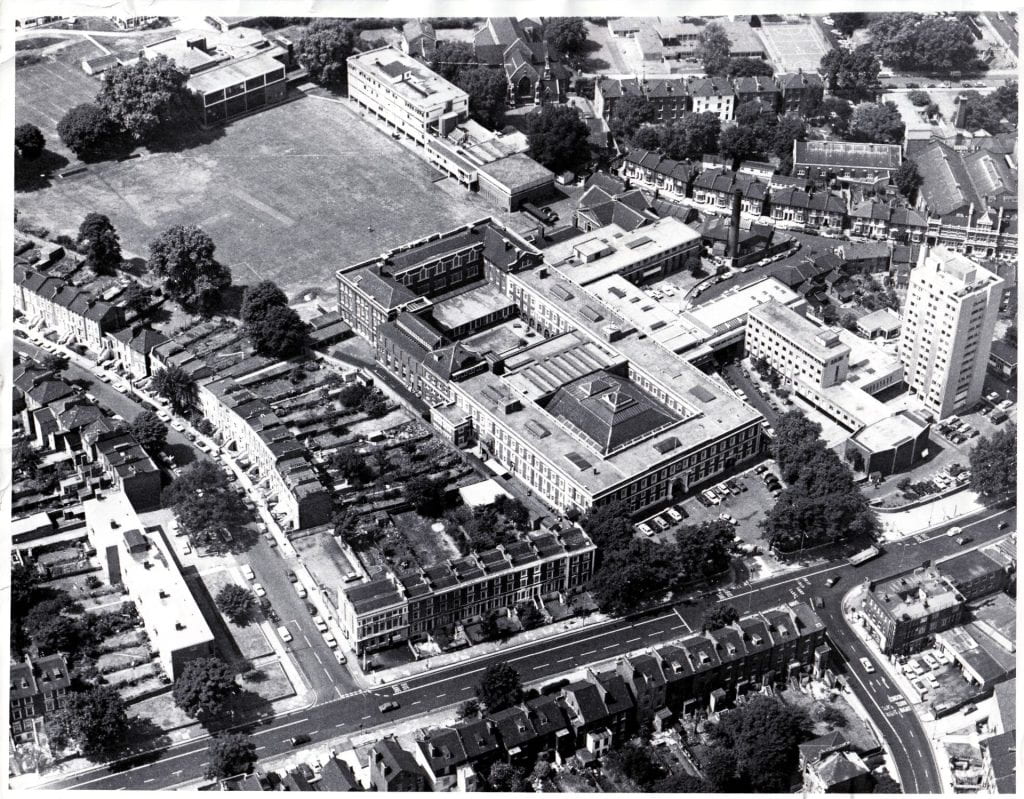

After the decommissioning of thousands of RAF aeroplanes, former pilots made money by buying them up and then taking aerial photographs to sell as postcards. This is an example.

Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

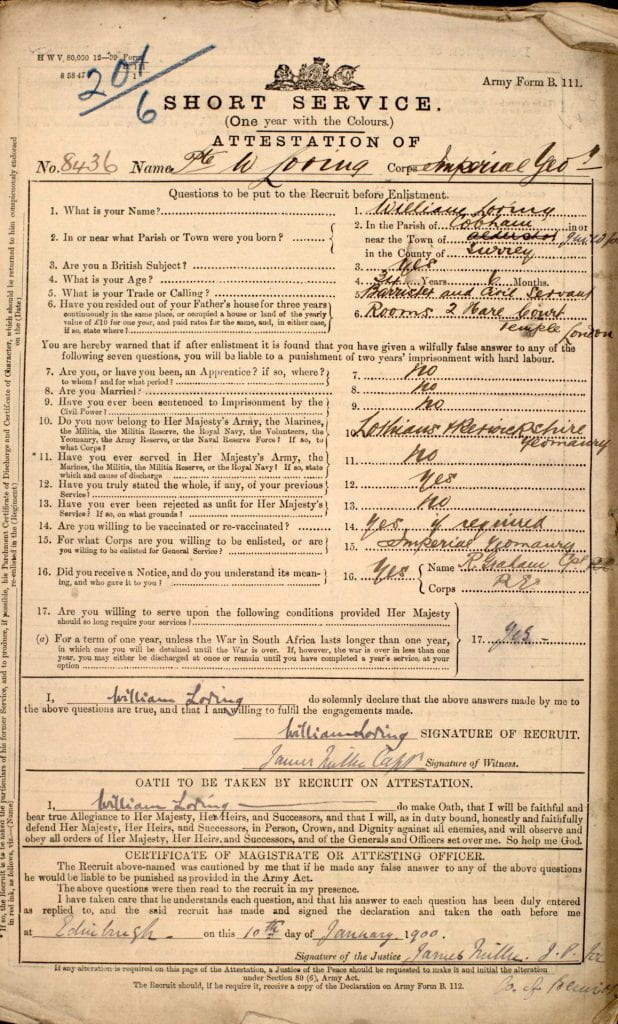

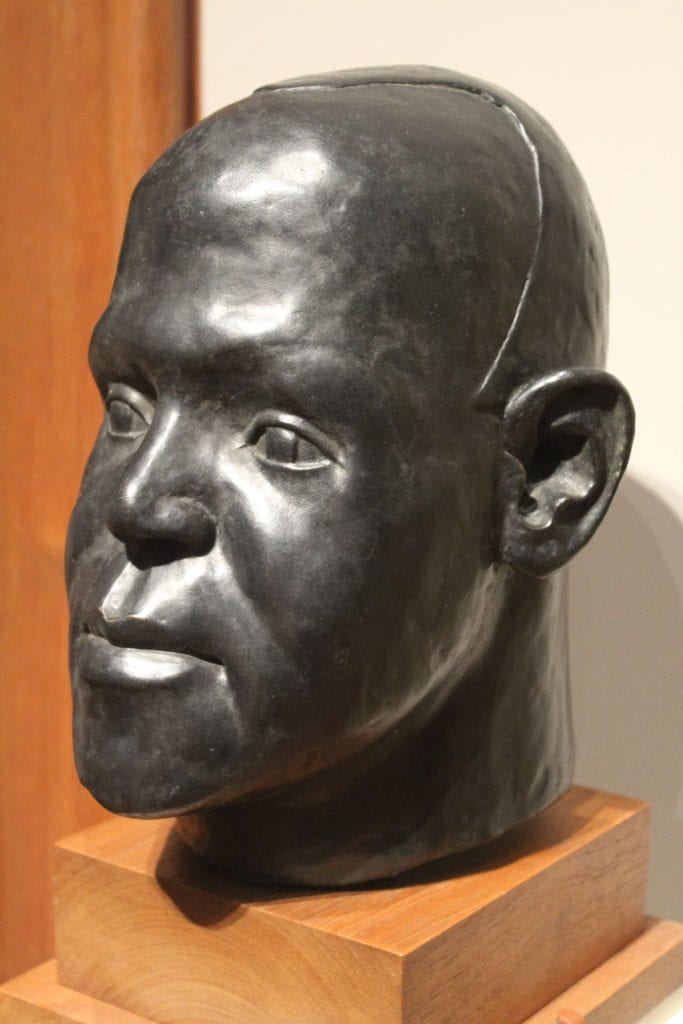

We see Goldsmiths after it survived the First World War. It was a very close run thing. The College’s first Warden (the equivalent of any university Vice-Chancellor) did not. WiIlliam Loring was 51 when he enlisted with his Boer War experience to be shot and wounded by a Turkish sniper at Gallipoli in the autumn of 1915.

He did not survive the amputation of his leg on a hospital ship and was buried in the Aegean Sea.

He left behind a widow and two children in Blackheath.

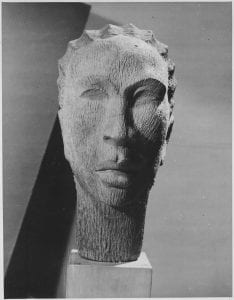

Bust of William Loring, Goldsmiths’ first Warden and commissioned after his death in 1915. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

He became the only British University chief to serve in combat on the front line and give his life for his country.

Loring is a mysterious figure. So much is known about him and at the same time so little. He was very close friends with the Riddle of the Sands author Erskine Childers.

As well as writing one of the earliest examples of the espionage novel in 1903 which was extremely influential in the genre of spy fiction, Childers would be executed by firing squad in Dublin during the Irish Civil War on 24th November 1922.

He was born in Mayfair, fought for Great Britain and Empire, but was also an Irish nationalist who took up arms for the cause.

Childers and Loring had been comrades in arms fighting for the British Army in South Africa during the Boer War at the turn of the century.

They dined and had good craic together as members of the Savile club in London’s Mayfair which was always known for its convivial companionship and encapsulated in the motto Sodalitas Convivium.

Erskine Childers, a volunteer in the Honourable Artillery Company in 1900 during the South African Boer War where he first met and became friends with William Loring who was a decorated soldier serving in the Scottish Horse. Digitisation of work by Arthur Weston and public domain image.

Childers insisted that his then 16-year-old son, the future President of Ireland, Erskine Hamilton Childers, promised to seek out and shake the hand of every man who had signed his father’s death sentence.

Childers’ final words spoken to the firing squad were: ‘Take a step or two forward, lads, it will be easier that way.’

Well over a hundred staff and student Goldsmiths’ alumni did not survive the carnage of the Great War.

They included one of the most brilliant and promising English literature lecturers in British academia William Thomas Young.

And their many names grace the memorial from W.B Lacy serving in the Civil Service Rifles to A McKimmie of the Royal Flying Corps. They were both casualties in 1917.

Second Lieutenant William Braithwaite Lacy from Huddersfield was 28 years old and buried in the Rocquigny-Equancourt Road British Cemetery at Manancourt in France.

23 year old Lieutenant Alexander McKimmie of the Royal Flying Corps was local to New Cross and went to the Addey And Stanhope School. His family were living at 5 Casella Road in 1911 and 42 Undercliff Road when he died.

He lies buried in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery in Belgium with the headstone inscription ‘In faith and hope beloved one we give thee up to God.’ His older sister Jenny was a London County Council teacher.

The Goldsmiths College building you see from the 1920s aeroplane, most likely with an open cockpit and photographer passenger behind the pilot operating a box plate camera, is hardly different from the Technical and Recreative Institute and Royal Naval School that preceded it.

The Naval School’s wall separating the main playing field from the upper playing field is clearly visible.

There are no Whitehead, Lockwood or Professor Stuart Hall Buildings. What are now teaching and rehearsal rooms for the Music and Drama and Performance departments is a charming Arts and Crafts late Victorian swmming pool built by the rich and philanthropic City Goldsmiths’ Company in 1891.

The College’s lovely Art Nouveau swimming pool was hardly a money spinner when the going got tough during the First World War. Deptford Borough Council had opened a spectacular complex of public baths within stone throwing distance in Laurie Grove ten years before. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Without emergency government subsidy Goldsmiths would have closed for good between 1914-18. Most of the men students went to war, along with most of the male staff. At one point there were only 15 male students enrolled for teacher training.

It became an all women’s college by default with the unique and virtually impossible challenge of training teachers with an art school by day and night, and teaching every subject imaginable as a night school for adults after 5 p.m- life drawing, embroidery, bricklaying, Latin, surveying, engineering and working with electricity.

To balance the books the staff voluntarily surrendered 15% of their salaries.

A working class Professor Tommy Raymont, who spent his teenage years from 13 to 18 bringing home a living wage to his parents (his father was the village blacksmith) as a pupil teacher, took over as Warden from the deceased William Loring- first as deputy Warden when Loring rejoined the army in 1914, then as acting Warden on his death in 1915, and finally with full appointment in 1919.

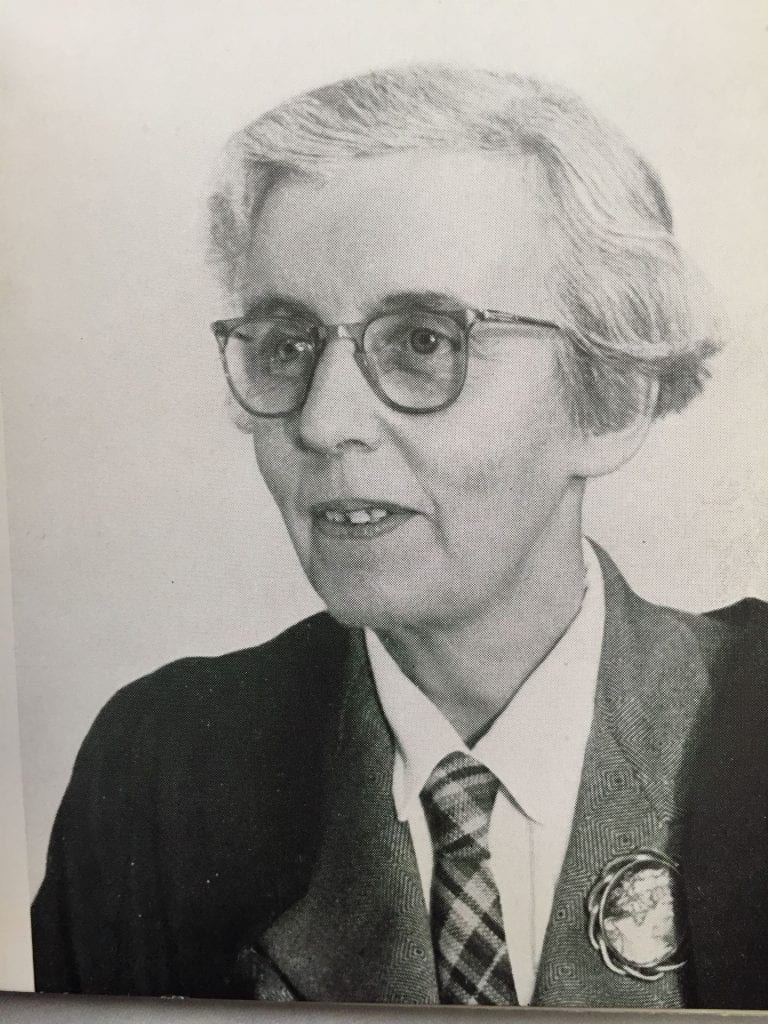

When the strain became unbearable, the Vice Principal for women students, Professor Caroline Graveson, would run the ship.

She was really another Warden in all but name.

As a team Graveson and Raymont were expert in the fine arts of higher educational wizardry.

It is 1907 and sitting down centre behold the mighty trio of Caroline Graveson (left), William Loring (centre) and Tommy Raymont (right with the massive drooping moustache). They were the first founding leaders of the College and to say it was ‘hard work’ is an understatement. Graveson looks half asleep dreaming into the distance, Loring as though he has just left a boxing ring and Raymont anxiously squinting perhaps with thoughts about the next crisis to overcome. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Budgets from the education committees of regional County Councils, the central government’s Board of Education, and London County Council fluctuated, never aligned and rarely broke even.

There had to be a discussion before agreeing to buy an overcoat to keep the nightwatchman warm- the heating had to be turned off overnight. Getting a telephone or even a typewriter was also significant expenditure and needed to be discussed at University of London Delegacy level.

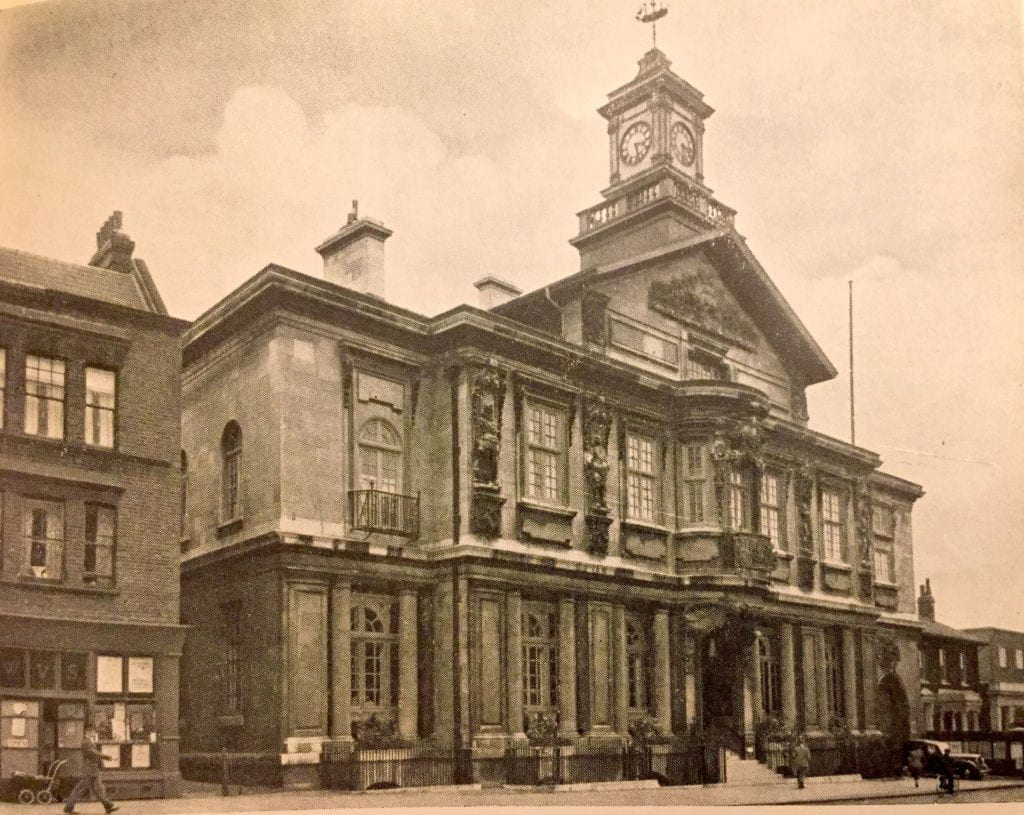

Loring, Graveson and Raymont were entrepreneurial within quite impossible constraints and all the time the local Deptford Council was plotting in the nearby Town Hall to take over Goldsmiths and lobbying for the College buildings and grounds to be the site for a big polytechnic or university of Science in south London.

Deptford Borough Council Chamber full of councillors, aldermen and local officials in the 1920s always jealously plotting to take over the Goldsmiths’ College grounds and buildings. They nearly succeeded during WW2. Clive Gardiner’s Art School held on in there and prevented the Council being able to say all of the London University College had fled to Nottingham and there was no reason why they should return. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

Goldsmiths’ College was the biggest teacher training department in the country. The Art School inherited from the Institute and hailing from 1891 had been top of the league table for winning all the national grants and prizes for its students.

When Loring died, Graveson and Raymont became the mighty duo and spotted the gap in the market for developing a nursery school teaching qualification. They even opened a nursery school taking in pupils in an annexe on the south east side of the main building which is still used to this day as a nursery for staff and students who are also parents.

They realised that the option to study general arts and science degrees, even if the curricula and exams were set externally, widened the student experience and scope for qualifications.

They saw music as having a future as an academic subject with degree status. They also saw the potential for adding a third year to the two year teaching certificate so students could take on an extra year for subject specialisation.

This would put the Goldsmiths students ahead of the competition as future specialist teachers of History, English, Geography and other subjects.

From the air Goldsmiths’ College in the year of the General Strike is a place without investment, and the estate is run down.

But it had survived largely because in 1918 the school leaving age had been increased from 12 to 14, and women were getting the vote and striving to be equal through education and the pursuit of careers.

There would be an expansion of secondary schools for boys and girls. Elementary schools needed to continue teaching children to the age of 13.

Graveson and Raymont regularly went to the new secondary schools to attend prizegivings and extol the virtues and indeed nobility of teaching. Graveson told schoolgirls to prepare themselves for the professions and follow their new ambitions.

Quite understandably they also said come to Goldsmiths to learn to teach.

Goldsmiths benefited from the millions of demobbed men returning to ‘Civvy Street’ including thousands who needed to be trained as teachers; so many in fact that in the academic year 1919-20 there were not enough halls of residence to accommodate them.

The ground floor classrooms of the Goldsmiths main building adjoining the two main corridors became temporary dormitories.

Graveson and Raymont also encouraged the ageing Headmaster of the Art School Frederick Marriott to attract 38 ex-Service students who had been given Government Grants for retraining to enlist in the School’s new commercial art courses based around illustration and design taught by Edmund J Sullivan, and Amor Fenn. From 1918 the young lecturer Clive Gardiner started teaching life drawing and he would go on to take over the headship at the end of the 1920s. Gardiner’s professional work was steeped in commercial illustration and public painting and design commissions.

When the Board of Education sent in the inspectors in December 1920, Goldsmiths was able to boast each and every one of the 38 ex-Service students were now earning a living in design and graphic art.

Britain was not the home fit for heroes promised in the Khaki General Election of 1918. But Goldsmiths’ College with its apostrophe and shabby gentility and social aspirations became a home fit for survival, improvisation and forbearance.

If there is a photograph to symbolise Goldsmiths’ College’s tenacity and staying alive against the odds and with a sense of humour, it is the one below.

‘Rule Britannia !?!- Gardeners never never never will be Gardeners.’ Students and staff at Goldsmiths in 1917. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

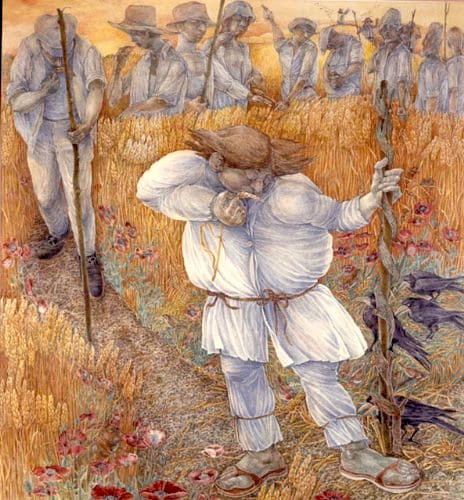

By 1917 German U-boats were sinking thousands of tons of merchant shipping and rationing was on the Home Front. It is a sad truth of war that the lessons of the past are rarely learned.

During WW2 the U-boats were back doing the same thing and nearly won the war for Hitler’s Nazi regime in the Battle of the Atlantic.

The large sports grounds and gardens of the College were ideal for change of use as allotments and the growing of fruit and vegetables in both conflicts.

In the Great War the work was done mainly by the women students. They were certainly pioneer land girls of London.

The cheeky looking man with bowtie and white socks sitting on the donkey far right also reveals another truth about the Goldsmiths’ spirit.

With some degree of mirth it could be said Goldsmiths has always been something of the donkey’s college and university.

To save money and before mechanisation, the management would buy a donkey rather than a horse to pull the rollers and gardening machinery.

Donkeys lived longer, consumed less feed, were cheaper to buy, didn’t have to go to the vets so often, worked harder, were more reliable and so much more stoic and dare I say it…masochistic than horses.

The Goldsmiths donkey had its own stable and was by far the most popular creature in the College with staff and students and it did not take long before the much-loved donkey was the unofficial mascot.

Never mind that the College’s coat of arms had a Goldsmiths’ Company leopard in the middle of it.

Wardens past, present and future might justifiably say when recruiting staff: ‘I want donkeys not leopards. They may complain more, but they stay longer and work harder. Yes, leopards are faster, but they eat people on the way and get better jobs elsewhere quicker than you can say hee haw.’

About 15 years ago several donkeys were seen hoofing it down one of the main building’s corridors. They were visiting in connection with a donkey sanctuary project and looked as though they were really coming home.

In 2016 Goldsmiths hosted the first George Orwell Studies conference and the presentation of an academic paper on George Orwell’s characterisation of the donkey Benjamin in Animal Farm titled: ‘Only Donkeys survive Tyranny and Dictatorship.’

The College staff from 1918 included men who had been jailed and humiliated as conscientious objectors and those who bore the mental and physical scars of conflict; sometimes succumbing a few years later to the damage to their lungs from being gassed in the trenches.

One shell-shocked lecturer would sometimes fall to the ground and cower under his desk when a lorry or car back-fired on Lewisham way.

True to the Goldsmiths’ spirit nobody laughed or blinked; the students continued writing and looking at their notes until the memory of trench bombardment passed and the discussion of George Eliot’s Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda continued.

With nearly a million untimely and violent deaths of mainly young people the Great Britain of 1918 was a society traumatised by grief and mourning. The established religions had been found wanting. How could God allow so much cruelty and suffering?

Spiritualism had so much credibility and charlatans were active in exploiting the sadness at large.

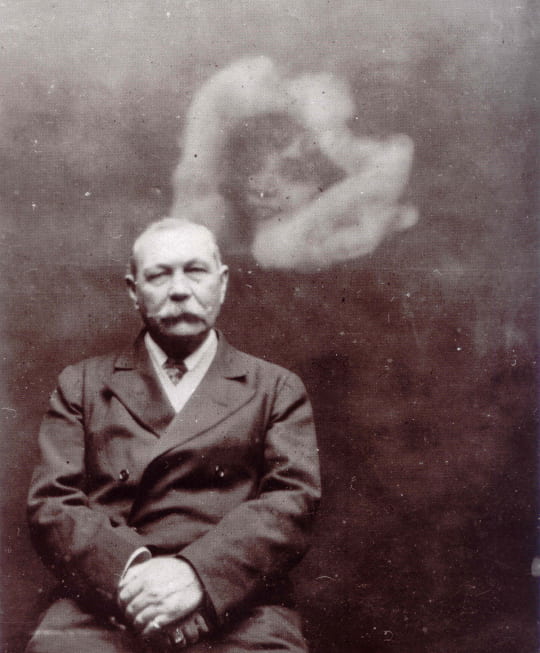

Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was certainly a believer.

Of course, when his son Kingsley died on 28th October 1918 from pneumonia contracted during his convalescence after being seriously wounded in the 1916 Battle of the Somme, he wanted to reach out to the beloved son he had lost, but Doyle had already begun presenting himself publicly as a spiritualist in 1916.

Spirit photograph taken [and most likely fabricated] of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by Ada Deane, 1922. Public domain.

At the end of 1918 Sir Arthur packed out the Great Hall of Goldsmiths’ College for a spiritualists’ meeting.

It was estimated one thousand attended. Tommy Raymont had not been consulted and the College may have been cleverly deceived about the meeting’s actual purpose.

Raymont was a rationalist and somewhat sceptical of excessively charismatic beliefs and religions. He had experienced his first wife dying prematurely from disease after only six years of marriage, lost his first infant son to pneumonia and he had no time for what he regarded as nonsense and superstition.

In October 1923, the Rev. George Vale Owen, wanted to use the Great Hall for a lecture on Spiritualism. He was a Church of England clergyman, avowed spiritualist and close acolyte of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Raymont made sure he was firmly and unequivocally refused.

By 1927 Warden Tommy Raymont had had enough of firefighting Goldsmiths’ College crises.

He said ‘it was a happy release for me when I walked out of the place for the last time,’ and only return as ‘an occasional visitor.’

He would enjoy his time after Goldsmiths travelling and teaching abroad, including the USA and writing the leading books on educational history until the most heart-rending tragedy for any father in his senior years would strike him so hard at the beginning of the Second World War.

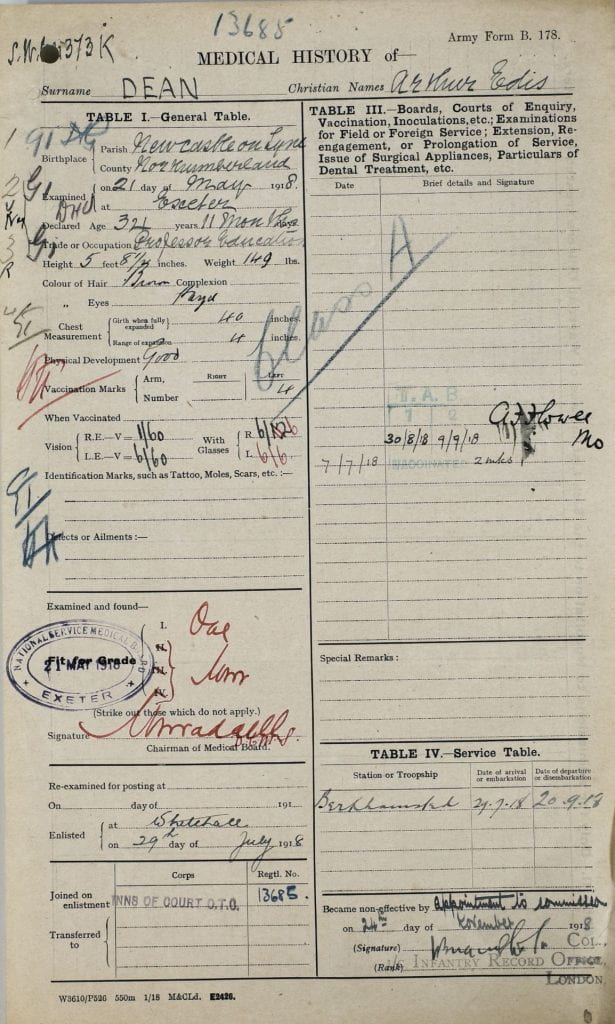

Now enter a suitably younger man full of optimism and robust health, one Arthur Edis Dean, ready and enthusiastic to take on the leadership and continue the policy of survival, entrepreneurship and spotting the next thing or two in terms of lucrative gaps in the market of teaching education.

Dean was a Marxist with an eye and nose for profit.

And in addition to being an academic prodigy and going to Durham University at the age of 15, Warden Dean was also a survivor. While serving as an army education officer at the end of the Great War he was struck down with Spanish influenza.

That was the Covid of its time and with no vaccines or remedies, it killed more people in the world than all the bombs, bullets and poison gas of the previous four years.

Dean was teaching invalided army officers in Oxford. Spanish flu was a deadly virus targeting mainly young men and women. He was among the most vulnerable and likely to die.

But Arthur Dean did survive and became the wizard Warden of Goldsmiths who genuinely did save Goldsmiths’ College and transform it as a Phoenix rising from the ashes.

He could rightly say ‘Oxford tried to kill me, but I got the better of it’- something no doubt a Durham University alumnus would enjoy saying and in his case with a great deal of personal feeling as well.

The military attestations of the first and third Wardens of Goldsmiths’ College

- Arthur Edis Dean’s British Army Great War file. He survived Spanish Influenza. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

- William Loring’s British Army Boer War file. He survived wounds in combat. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

We are now flying in the air with the RAF in 1946 and 1947.

Photographic reconaissance is overflying Britain and mapping the ground of a capital city battered and devastated by high explosive incendiary, the V1 doodlebug flying bomb and the world’s first intercontinental missile of mass destruction, the V2 rocket bomb.

The low flying plane on 9th July 1946 took an aerial picture which can be seen clicking on the link below.

The centre of the image captures the Goldsmiths’ College campus in recovery from the ravages and destruction of not only the German Luftwaffe but Deptford Borough Council.

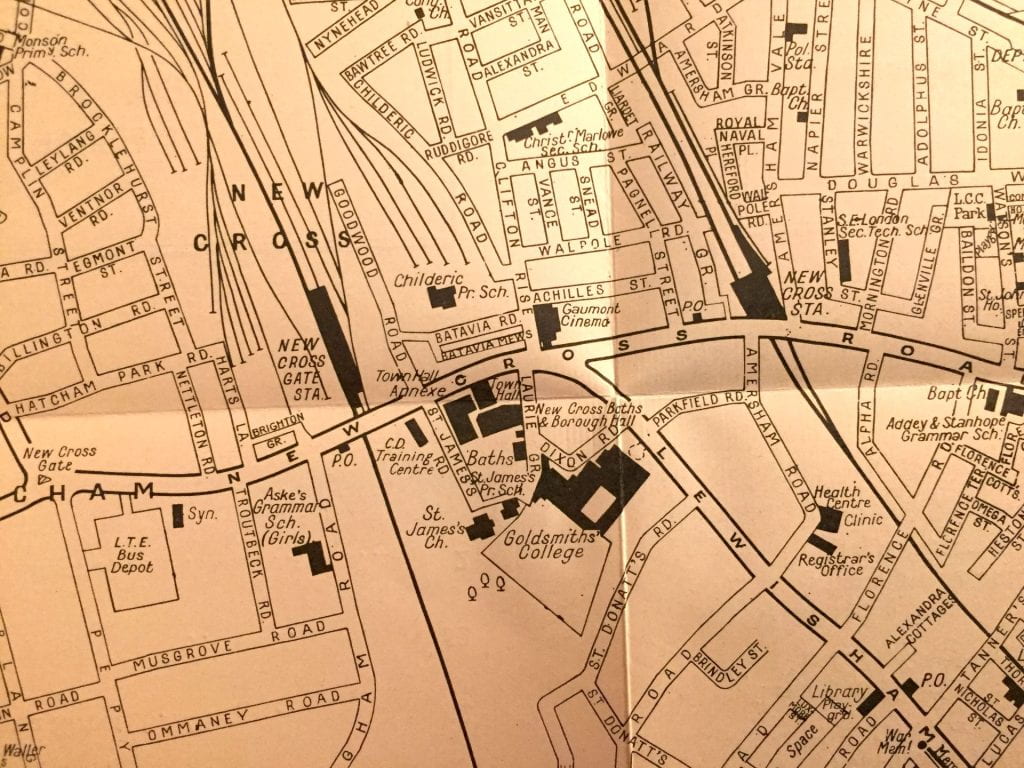

The upper backfield is still divided and used as allotments, but the roof of the main building has now been repaired. The devastation and large bomb site for the V2 disaster of 25th November 1944 is still evident. The junction of New Cross Road, St James’s and Goodwood Road is extensive white wasteland.

Date flown: July 9, 1946. Sortie: RAF/106G/UK/1633. Photographer: RAF

Aerial Photo – RAF_106G_UK_1633_RV_6218 1946

On 29th May 1947 the RAF overflew the College again and by clicking on the link it is possible on close inspection of the image centre and middle right to observe more redevelopment and refurbishment of the main building.

When zooming in to the curve of Dixon Road it is possible to see the charred husk ruins of the College’s burnt-out swimming pool. However, the college is now ready to fully resume teaching for all day and evening courses starting October of that year.

Date flown: May 29, 1947 Sortie: RAF/CPE/UK/2112 Photographer: RAF

Aerial Photo – RAF_CPE_UK_2112_V_5153 1947

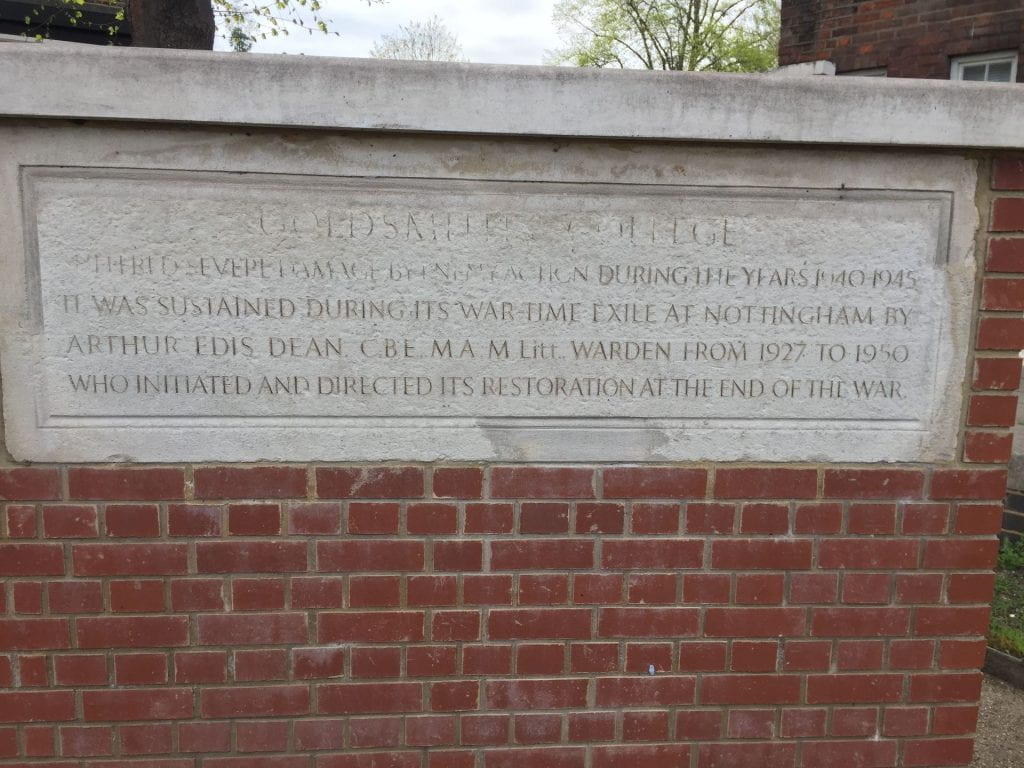

Warden Arthur Dean’s miracle of bringing about the resurrection of Goldsmiths is commemorated in a special tablet block now situated in the front garden to the left of the main building close to what used to be the entrance to the women’s corridor.

Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

The tablet’s inscription is a little worn from wind and rain, but it is possible to appreciate how it confers almost Moses style status on Arthur for bringing the college back from Nottingham as though he was leading his tribe from ancient Egypt with God separating the Red Sea and taking the Israelites to the land of milk and honey.

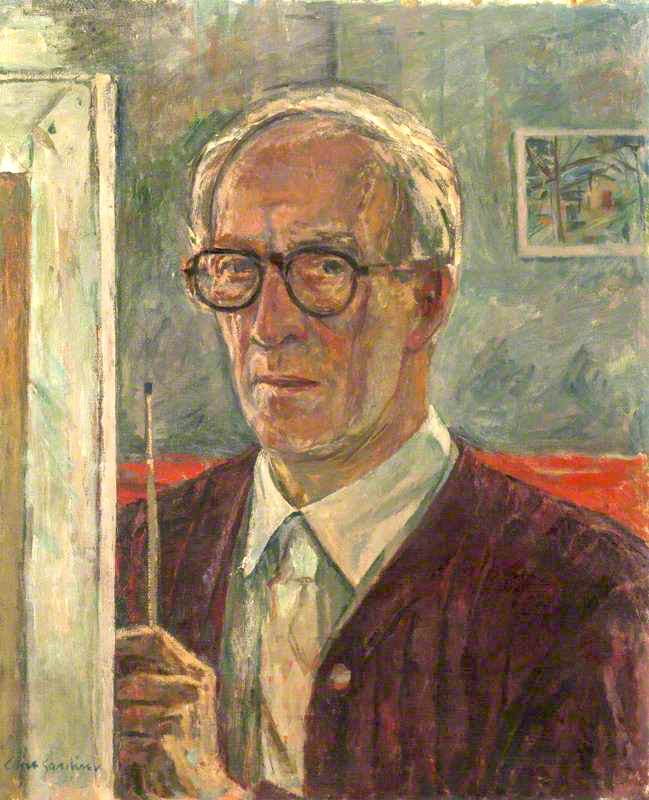

Arthur Edis Dean- the third Warden of Goldsmiths’ College serving from 1927 to 1950. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Caroline Graveson remained the grounded bridging force and anchor when Warden Dean arrived to take the reins of Goldsmiths. She was needed.

The Wall Street crash and Great Depression heralded the 1930s and a decade of social, political and economic turbulence.

The new DG team of Dean and Graveson took on and developed excellent ideas already seeded.

Arthur Edis Dean, CBE, MA, MLit, Warden of Goldsmiths College (1927-1950); Portrait by Clive Gardiner; Goldsmiths, University of London Art Collection. Estate of Clive Gardiner. All rights reserved.

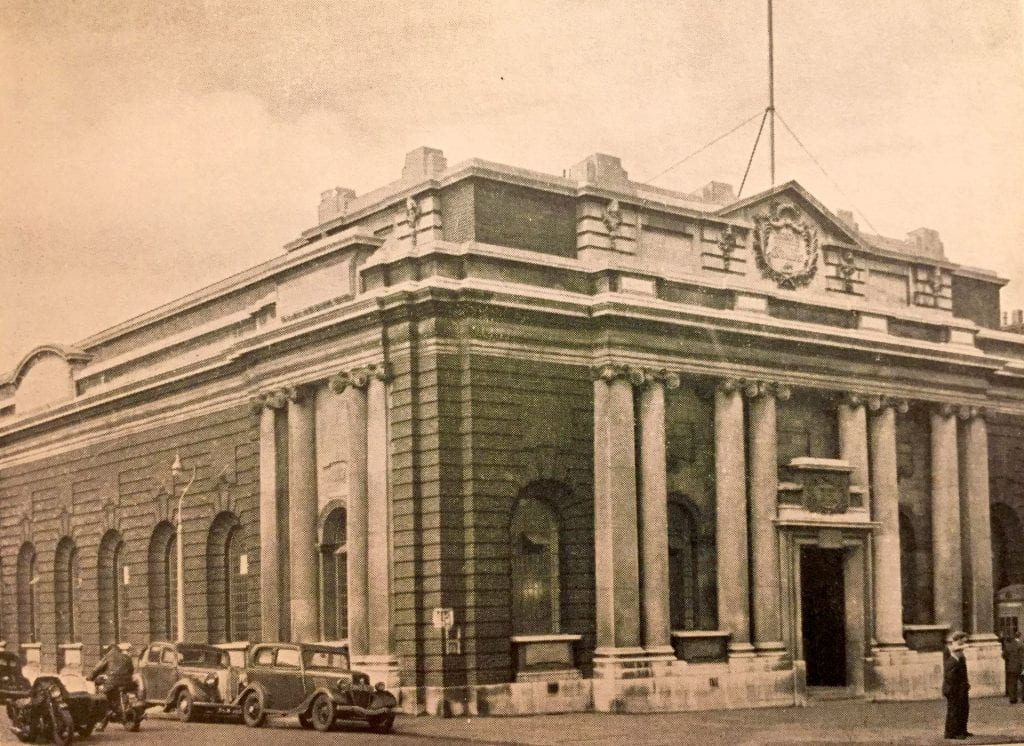

Building and engineering skedaddled down Lewisham Way to the new South East London Technical Institute and in came a dynamic new force in adult education- music, literature and the arts at night and the shoots of what would later become night school degrees and the inspiration for the Open University.

A third specialist year for the two year teaching certificate would be the inspiration for the future three year degree in education.

Health and exercise were the fashion and part of the politics of the 1930s and a demand for physical education teachers was another opportunity and enterprise expanded into a specialist third year certificated course at Goldsmiths.

This is why at one stage the College had two gymnasiums.

Clive Gardiner became headmaster of the Art School in 1929 and turned it into a dynamic force for a British style in post-impressionism as well as public art and industrial, manufacturing and advertising design.

The Black Magic chocolate box, Art Deco London Transport Underground posters, Radio Times magazine covers and the new farthing coin were just a few of the iconic images created by Goldsmiths Art School alumni during this period.

Wizard Dean also looked ahead to a future globalised market in higher education.

Private students from all parts of the British Empire would become future leaders of postcolonial countries achieving self-determination and independence and included the Indian cricketing hero Cottari Subbanna Nayudu.

These were boom years and by 1938 the College Reserves of £14,000 were used to buy 24 acres at North Cray in Sidcup including the former home of Lord Castlereagh, where it is believed he shot himself.

£14,000 in 1938 has the purchasing power of about £1,162,062.54 in 2023.

Woollett House was converted into a woman’s hostel and renamed Loring Hall. The playing fields are still used by Goldsmiths to this day.

But the years of economic boom would as we all know turn into an unwelcome explosion of global violence and war.

The class of 1937 would graduate in 1939 with the full expectation of being called up into the armed services. We will focus on the fate of some of those students in the following years.

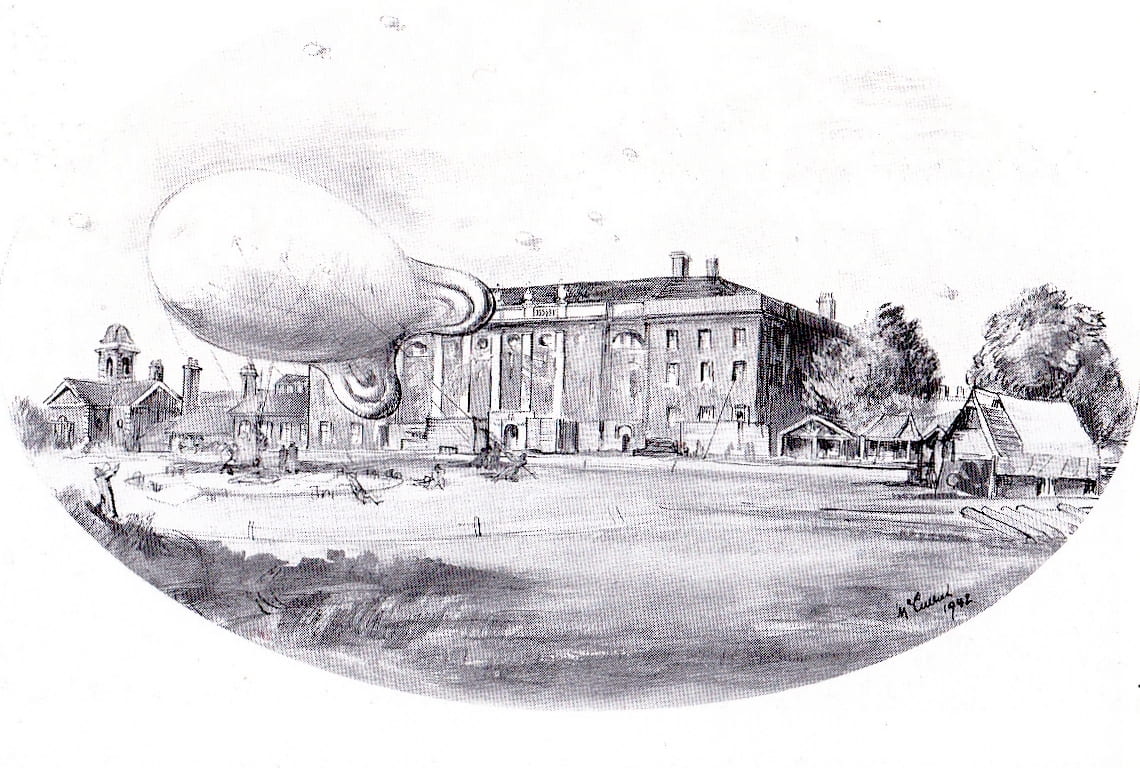

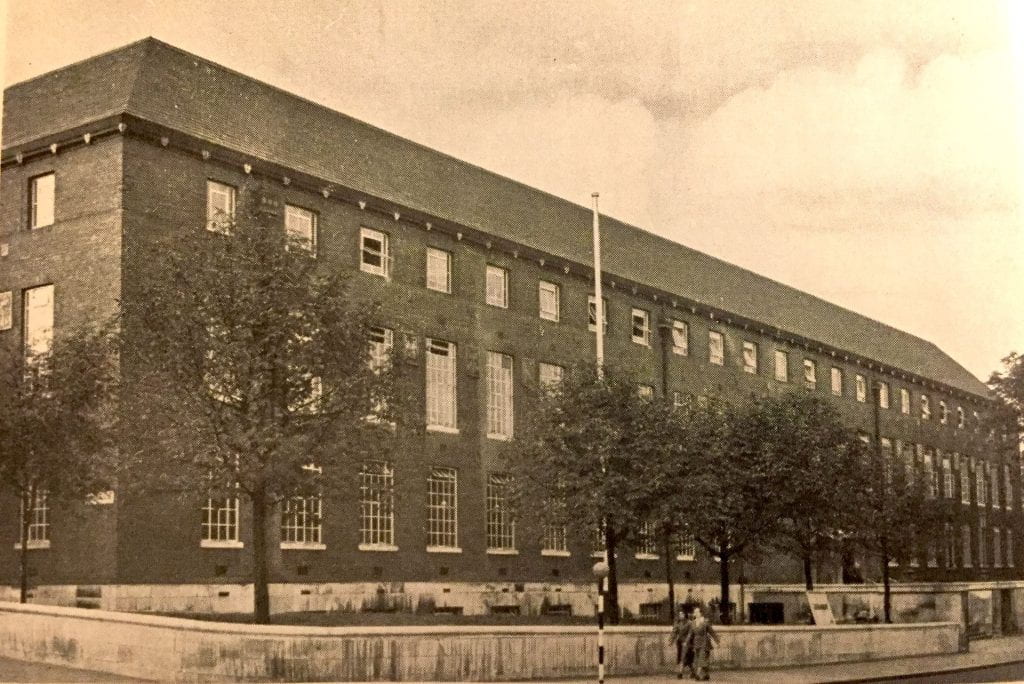

Warden Dean and his staff had to evacuate the College to University College Nottingham and Goldsmiths in New Cross would experience an exile lasting nearly seven years.

M. McCullick’s ‘Barrage Balloon backfield’ watercolour dated 1942 but still including the former Chapel tower which had been largely knocked down by a balloon removed from its moorings by a storm in October 1939. This is a detailed depiction of one of the ‘flights’ of 902/3 Balloon squadron based at Goldsmiths throughout the war. Two auxiliary airmen stationed here would be killed in June 1944 when a V1 flying bomb hit one of the barrage balloons and exploded in the middle of the playing field. Image: Goldsmiths Art Collection. All Rights Reserved.

The campus would be invaded by Deptford Borough Council, the RAF with a Barrage Balloon unit who together with the Luftwaffe would nearly destroy it.

The Barrage balloons arrived as soon as War was declared by Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain on 3rd September 1939. They were supposed to be raised during an air raid with the sound of the sirens to keep enemy aircraft high and in danger of crashing into the cables.

It seems the cables tethering the Goldsmiths’ balloons were not strong enough and one of the hydrogen filled massive air bags soon became a low flying battering ram smashing the tower on top of the former Royal Naval School chapel and tearing swathes of slate tiles off the main building.

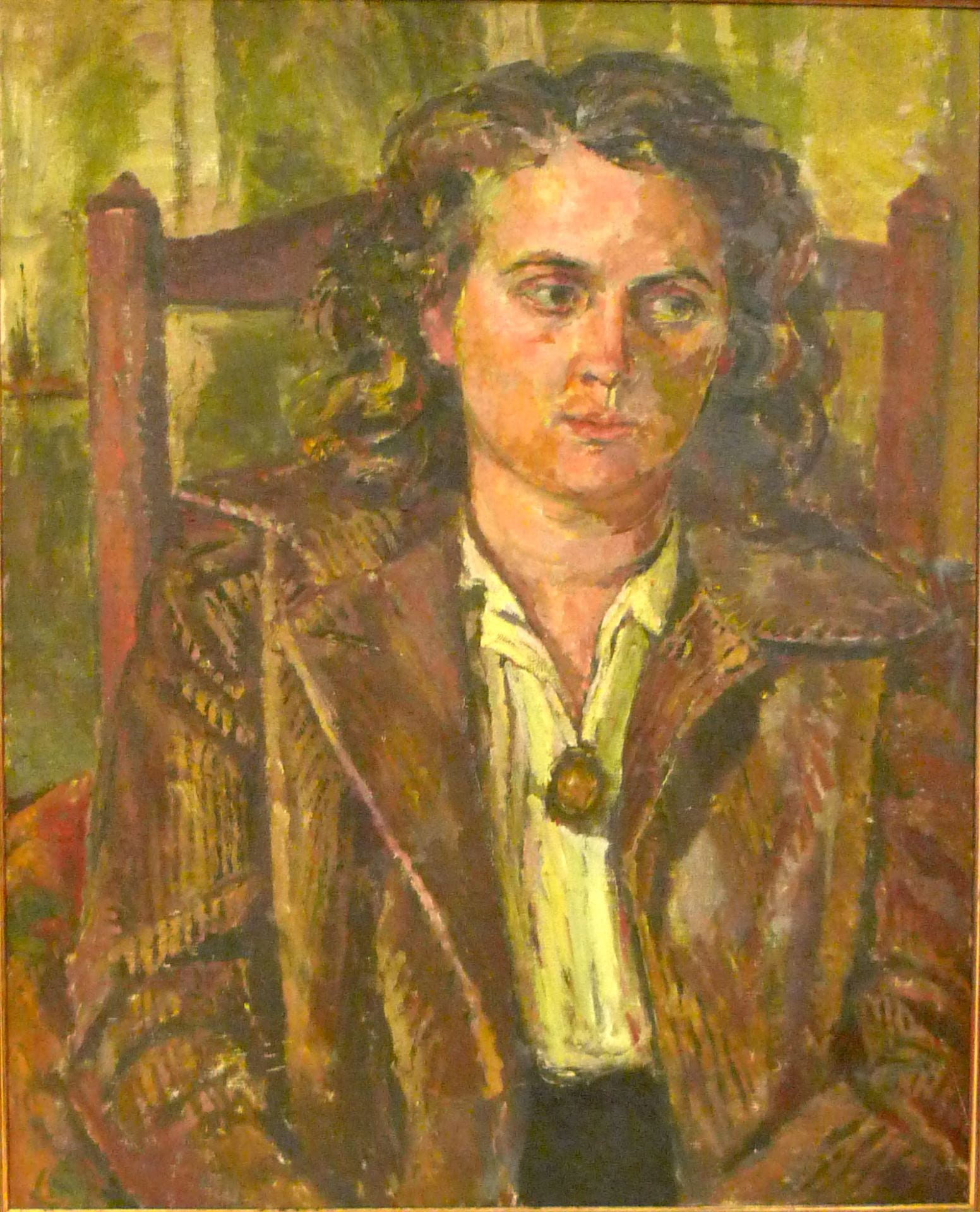

Art School Headmaster/Principal Clive Gardiner and his long-term lover, former art student and lecturer Betty Swanwick stayed at New Cross to keep the Art School running throughout the war. J. McCulloch was another full-time lecturer volunteering to stay in London to keep the Art School running.

With their cadre of part-time lecturers they fought to keep the maurauding vandals of Deptford Borough Council at bay.

Image of Deptford Borough Council Official Guide post WW2. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

The Art School occupied the purpose built Blomfield block facing the ‘backfield’ (now called the College Green) completed in 1908 with generous funds from the City of London Goldsmiths’ Company.

They found a way of fitting doors in the corridors so they could lock out what had been an invasion of Deptford’s civil defence forces who seemed intent on disrespecting and causing the most damage they could do to the rest of the College’s New Cross estate.

We can give them the benefit of no proof of intent, but we can certainly assign negligence and indifference to the idea that Goldsmiths would ever continue as a higher educational insitution when the war was over.

The Council decided Goldsmiths would become the centre of civil defence for Deptford. ARP (Air Raid Precautions) headquarters and control moved in.

The swimming pool became the Borough’s emergency mortuary for mass casualties. The Borough’s entire First Aid organisation moved in and eventually constructed a purpose built structure at the back of the College with an entrance to the road called ‘Barriedale’ to be run as the emergency medical services centre for all of Deptford. After the war it would be used for Art School crafts such as ceramics.

The upper playing field was turned over to war-time horticulture and strips of allotments and the RAF turned the backfield playing field into a permanent quagmire as their heavy vehicles drove in and out with all kinds of enemy aircraft tracking equipment and devices as well as replacement Barrage balloons.

The sports pavilion became a hut fitted out for air defence.

The army also moved in nearby with an anti-aircraft battery. If fugitive Barrage balloons did not do for the main building, there was a risk of unexploded shells falling back down to finish off the job.

Sadly, the best of Deptford’s finest ARP Wardens could not do some basic firewatching at the end of December 1940 and Luftwaffe incendiary bombs ignited all over the main building’s roof.

The 29th December 1940 was when the City of London’s famous medieval Guildhall became a burnt-out shell. Goldsmiths did not fare much better.

The German bombers had discharged an entire canister of incendiaries onto the roof and because there were no firewatchers there on duty to put them out, almost the entire top of the building was ablaze.

Fifteen auxiliary fire appliances were sent to Goldsmiths, but did not have long enough ladders to fight the conflagration on the outside. They had to go inside and pull hoses up the narrow stairs to fight the inferno.

The roof, the top floor of three sides of the buildings, including the library along with thousands of books, most of the staff rooms, cloakrooms and common rooms, and all the Chemistry, Biology and Geography laboratories and classrooms were destroyed. The main building’s distinctive tall neo-Wren chimney stacks were lost forever.

The destruction of the top floor of Goldsmiths’ College by incendiary bombs 29th December 1940 along with its library. Images: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

The Great Hall, Blomfield Art School block and kitchens just survived, but the rest of the College was little more than a ruin. More bombings and fires 19th March 1941, 22nd March in 1944, and 26th June 1944, added to the damage.

A fire in the Swimming Pool in May 1945 left only the walls standing and in need of demolition. This was not caused by enemy action. The most likely cause was faulty wiring, a discarded cigarette, or unattended coalfire in what should have been Deptford Borough Council’s much needed mass casualty mortuary.

For the rest of the war the Great Hall was filled with a smouldering pyramid of charred and sodden library books.

On a clear night you could look up through the open roof of most of the main building to marvel at the stars above and watch the German bombers ducking and diving to avoid the searchlights and anti-aircraft gunfire.

Clive Gardiner, Betty Swanwick and the College’s brother accountants John and Alfred Mansfield stayed in New Cross to effectively spy and report on the fate of its buildings as it was blown up and burned down around them.

John remained in the accountants’ room at the front of the building just by the main door (which in recent years has been turned into an open reception area).

The Mansfields had a secret knocking code and so most of the time John could ignore the comings and goings of ARP Wardens, Deptford’s Heavy Rescue Squad, First Aid Post personnel, the Londoners’ Meals Service, and Auxiliary Air Force.

Alfred, who had been the Art School’s registrar, infiltrated Deptford Council as part of its war-time administration and became Goldsmiths’ College spy on the inside.

Alfred Mansfield; Portrait by Clive Gardiner; Goldsmiths, University of London Art Collection. Clive Gardiner Estate. All rights reserved.

Consequently, Warden Dean in Nottingham was continually tipped off and informed of threats and disasters before he received official notification.

And Deptford Council tried everything they could think of to prevent the College ever returning.

The war-time Londoners’ Meals Service seems to have been a London County Council operation. They insisted they could not cook in the kitchens, distribute and deliver their meals around London if any attempt was made to repair the damaged parts of the buildings.

This meant builders could not go in until after VE and VJ days in 1945.

Deptford Borough Council also spent thousands of pounds building an underground air defence control centre, which in the end was never completed for operational use. It is sited at the back of what is now the College Green just before the ground rises to what is the Professor Stuart Hall building.

In 2010 an entrance to the bunker was uncovered during the new building’s construction above it.

There was some discussion at Deptford Council in 1945 that it might be suitable for development into an underground shelter and civil defence centre in the event of nuclear war.

The legacy of this folly is a continuing and potential sink hole, which will have to be dealt with should there ever be any building on that part of the green.

In June 1943 the Mayor of Deptford convened a Town Hall conference to propose turning the Goldsmiths College site into a community centre for young people.

Deptford Council’s Town Clerk even served a Requisition Order in Captain Mainwaring Dad’s Army style to seize the Lecture Hall (former Chapel) to be used as an extension for the Council’s part-time nursery.

Warden Dean summoned the intervention of the Board of Education. He could be forgiven for fearing Deptford Council might next declare Martial Law and evict the Art School and anything else remaining of the College’s presence.

- Betty Swanwick by Clive Gardiner. (1915-1989) Lecturer & Head of Illustration Goldsmiths School of Art 1936-1969; Goldsmiths, University of London Art Collection. Estate of Clive Gardiner. All rights reserved.

- Gardiner, Clive; Self Portrait, Principal of Goldsmiths College School of Art (1929-1957); Goldsmiths, University of London Art Collection. Estate of Clive Gardiner. All rights reserved.

The endurance of Goldsmiths College’s School of Art during the Second World War in New Cross is one of the rather neglected chapters in the University’s history.

There was courage and stubbornness on the part of Clive Gardiner and Betty Swanwick who insisted on staying in London during the Blitz of 1940 to 1941 by high explosive, oil bomb and incendiary and 1944 to 1945 by V1 and V2 Flying bombs.

The courage and resilience were also shared by the artists and life models coming to teach in New Cross part-time and their students.

They included Quentin Crisp who coincidentally was a graduate of London University’s first Journalism Diploma course at King’s College in the 1930s.

Quentin Crisp NYC 1992 Ross Bennett Lewis CC BY-SA 4.0

In 1944 art students recalled how Quentin ‘walked like a king’ and offered very profound statements for the life drawing classes. They remembered his exotic persona, red hair and very white skin. He never walked around the room to see how his portraits were progressing.

He would sometimes stare at a crossword pinned to the wall and fill in the words during the breaks. He ‘looked like something out of the Renaissance.’

His reputation reached legendary status when a bomb dropped outside the college and blew in the window of the life room. He continued to hold his pose without batting an eyelid.

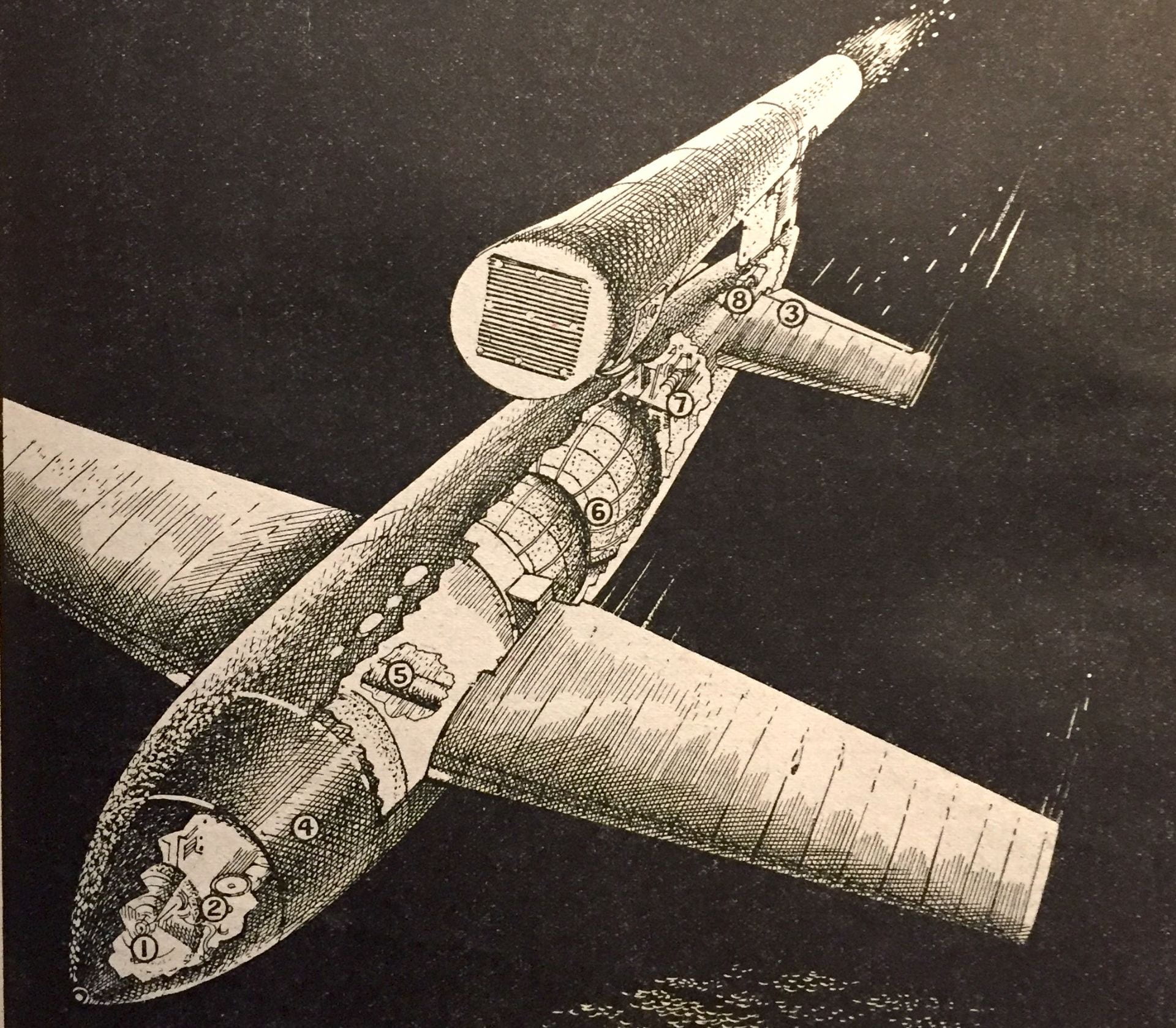

V1 and V2 stood for Vergeltungswaffe 1 and Vergeltungswaffe 2 and ‘Vergeltungswaffe’ in German means ‘Vengeance Weapon.’

It is possible Quentin Crisp’s famous pose with the life room window blowing in took place on the very day Clive Gardiner and John Mansfield had a very lucky escape when a V1 Doodlebug with a ton of explosive landed on the backfield.

This was Monday 26th June 1944.

They had just walked through the detonation area of the backfield before entering the Blomfield building.

They would have heard the flying bomb’s distinctive low throbbing engine as it came up from the south east and then the silence which presumably was the pause of silence that enabled them to reach the doors in time and duck down in the ground floor corridor.

It is sobering to think that a few car lengths separated their deaths and the rest of the people in the building and the massive explosion on the College’s famous playing field.

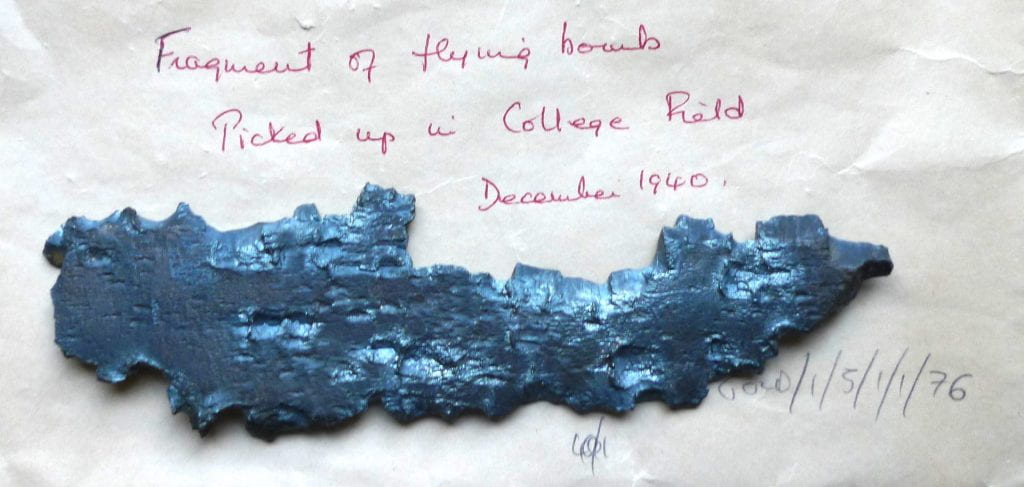

The blast sent deadly shards of shrapnel in all directions. It is presumed that a jagged and ugly piece of bluish metallic shrapnel in the Goldsmiths Special Collections was picked up by Clive for the archives.

It is rightly labelled as a fragment of the flying bomb retrieved from the College field, but the date December 1940 is clearly wrong. Those writing the description most probably confused it with the incendiary raid of 29th December which did so much more damage to the main building.

Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

In the years since, it is a shame that Goldsmiths and indeed the wider community of Deptford and Lewisham seem to have largely forgotten that two Auxiliary Airforcemen were killed on the College’s main playing field in that explosion.

They did not have enough time to run from the path of the bomb’s horrible descent, or they bravely stood at their posts in charge of the barrage balloons.

The World War Two Barrage balloon had a capacity of 20,000 cubic feet of hydrogen and the envelope was made of two-ply rubber-proofed cotton with an aluminium powder finish to reflect the heat of the sun. Image: War Illustrated, 16th December 1939, page 441.

There is no evidence that Goldsmiths or the local authorities have ever commemorated them. Not even the RAF has left any monument to their memory or some mark to their sacrifice.

Leading Aircraftsman Ernest Moody was 40 years old and serving in the 902 Balloon Squadron at the 2/47 barrage balloon site based in St Donat’s Road. He is buried in St Mary’s churchyard Bexley and was survived by his widow Lucy who arranged for the inscription ‘Peace on earth. Good will toward men’ on his gravestone.

He was killed with Leading Aircraftsman Richard Henry Mann who was 44 years old and lies buried in the Hither Green cemetery.

His widow Mary Elizabeth living in Downham Kent commissioned the inscription ‘For evermore. Stories of the fallen’ to be carved on his gravestone.

The Auxiliary Air Force Barrage Balloon squadrons are credited with bringing down around 300 VI flying bombs between 1944 and 1945.

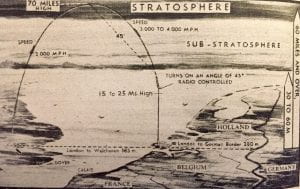

In late 1944, the weekly magazine War Illustrated explained the technology and science behind the V1 including the automatic pilot. Its doodlebug sound was caused by an impulse-duct engine- A: air stream through the grill to be compressed; B: simultaneously with the injection of petrol. The mixture is then fired by a spark, thus closing the valves. The white-hot gas is then emitted; C: propelling the bomb on its flight

But when the rockets’ short fins caught in the balloon cables or they ran into the balloons themselves the RAF people below would often be caught in the force of the resulting explosions and pay a terrible price.

Another chilling object from the Second World War left in the College archives is a piece of shrapnel which blew through an office door.

Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Perhaps it was retrieved by John Mansfield when a high explosive bomb detonated in Lewisham Way at the front of the College and showered the entrance gate with flying hot fragments and metal shards.

The photograph below is of the Goldsmiths’ College entrance in 1947 after the immediate postwar restoration.

The entrance pillars and wall remnants are pitted with shrapnel indentations and the metal gates have long been ripped off and mangled by blast force.

The front of the refurbished Goldsmiths’ College in 1947. Image: Goldsmiths College Archives and Special Collections. All rights reserved. It was decided to clear the area of trees and shrubs and erect a flagpole in the centre around which taxis and vehicles could more easily enter and leave after discharging their occupants.

A proper record of Goldsmiths staff and students who died ‘For Freedom and Honour’ during the Second World War was never compiled and it can be presumed this is because the College had to return from Nottingham to a building site where the library and archives records centre had been destroyed.

The returning to New Cross operation was inevitably organised chaos.

One student starting in the autumn of 1946 informed the History Project that the inside rooms resembled the Pompidou centre in Beaubourg Paris. All the heating pipes and electrical cabling had been installed, but the plastering was still going on during classes.

The winter of that year was one of the harshest in living memory and the country struggled with fuel shortages and power cuts.

The snowbound winter of 1946-7 was so bad the railway network struggled to distribute coal to power stations and domestic heating depots. CC BY-SA 2.0 Image by Arthur Shaw ‘Winter 1947, snowbound bus, Castle Hill, Huddersfield’

At Goldsmiths, carpenters were still putting the windows in, so the students left their desks and sat on the water pipes running along what should have been plaster-boarded walls.

One 1940s alumni chuckled: ‘We soon became the piles and chilblains generation.’

When it came to restoring the remembrance panel for the College’s war dead there was only enough time and money to add a small section referencing the dying in two world wars including 1939 to 1945.

The Goldsmiths ‘They Died For Freedom And Honour’ memorial tablet when photographed in 1921. It is practically the same as it is now apart from the central section which now refers to both World Wars. It is assumed the original wooden carved wreath was damaged during WW2 and has not been restored. Image: Goldsmiths Archives/Special Collections.

No names or regiments. Consequently, apart from an obituary in the College magazine in 1941 and reference in the 1955 history The Forge, the College’s England Hockey player and physical education lecturer, Percy Thomas Rothwell did not receive a public eulogy until the online Goldsmiths History Project provided one in April 2023.

Register of students who entered Goldsmiths’ Training College (for teachers) September 1937. Image: Goldsmiths Special Collections.

Over time the project will try to recognise all the others. We will start with the Teacher Training Department’s class of 1937 to 1939.

The students finishing in that year had no time to return to New Cross for any congratulatory ceremony.

They had started their probationary teaching employment when war was declared.

Cuthbert Edward William Jones had gained his school certificate at Ebbw Vale County School and in his final exams at Goldsmiths in July 1939 qualified as a teacher with a Class II certificate.

He was registered with the Board of Education as a teacher on 1st August 1939.

He began his teaching career in a temporary supply post at the Moorland Road Elementary School in Cardiff until called up on February 20th 1940. The school later became Moorland Road Primary though damaged and partly rebuilt as a result of the Cardiff Blitz. It was attended by Dame Shirley Bassey after the war.

He joined the RAF to be trained as a wireless operator and served with the 84 Squadron which flew Bristol Blenheim bombers in Middle East operations during 1941. Unfortunately, the squadron was transferred into the chaos of Japan’s invasion of Singapore, Malaya and Java in January to March 1942.

Cuthbert’s squadron were outgunned, outmanoeuvered, poorly led and poorly equipped. In a seven day retreat across Java they were continually bombed and strafed by Japanese air attacks and realised too late that they had the wrong colour camouflage nets with bright yellow colours intended to blend with the desert providing garish targets against the dark green jungle terrain.

Being taken prisoner of war would offer no respite.

Aircraftman 1st Class Cuthbert Jones suffered terribly at the hands of Japanese soldiers who did not respect their enemies when surrendering.

The fact he survived as long as he did is a testament to his courage and endurance.

His squadron had only recently arrived in tropical conditions and had no time to acclimatise to the heat and humidity.

As POWs they were denied a sustainable diet. The camp food lacked vitamins and protein.

Medicines were very scarce and the Japanese would rarely distribute Red Cross supplies and parcels.

The dreadful living conditions, shortage of food, water and sanitary conditions, and the ravages of tropical diseases such as malaria, made worse by the surrounding swamps and dirty water, combined to create a living hell.

Few of the RAF men had received any proper inoculations prior to their arrival in the Far East.

Cuthbert died in a POW camp on the island of Java on 29th November 1943 at the age of 26.

His name is commemorated on column 428 of the Kranji Singapore memorial.

His is one of over 24,000 names of Allied personnel whose bodies were never found.

It is impossible to imagine the grief of his 63 year old widowed mother Mrs Frances Mary Jones when she received news from the Red Cross of her only son’s death.

A picture gallery of Cuthbert Jones’ service in the RAF during WW2 and ending with his death in Java while a prisoner of war at the end of 1943. He was a wireless operator for 84 squadron which flew Blenheim bombers in the Middle East in 1941 and 1942. They were posted into the disastrous defence of Singapore and Malaya and Cuthbert was one of 30,000 allied servicemen captured on the island of Java.

- The crew of Bristol Blenheim Mark I, L1381 ‘VA-G’, of No. 84 Squadron RAF, prepare to board their aircraft at Menidi/Tatoi, Greece, for a raid on an Italian port in Albania. Image: Imperial War Museum. CM 264.

- The Commanding Officer of No. 84 Squadron RAF briefs his aircrew before a training sortie at Shaibah, Iraq in 1941. Image: Imperial War Museum CM 109.

- RAF operations in the Middle East and North Africa. 84 Squadron 1941-42. Image: Imperial War Musuem. CM 109. Blenheim aircraft based at Shaibah, Iraq, flying in formations of three over the Iraqi desert.

- The inscription on the Kranji War Memorial where Cuthbert Jones is remembered. Image: by Nick-B CC BY-SA 4.0

Pilot Officer Henry Richard ‘Dick’ Cutten’s promising teaching career was also cut short when he was called up into the RAF. Like Cuthbert Jones, he had qualified with Class II performance in his final exams in July 1939. When in New Cross he had lived in the Aberdeen Hostel in Blackheath. Cuthbert had boarded in the Grove Hostel in Lewisham.

Dick Cutten started teaching at a school in Cowes on the Isle of Wight, then moved to a post with a London County Council School in Acton, and travelled with his pupils to Dawlish in Devon on evacuation in September 1939.

Dick was an all round sportsman winning a ‘purple’ playing badminton for the University of London, and winning chess championships for the Bognor Regis chess club. He also excelled at soccer, cricket and tennis.

He was 27 years old after completing his RAF training as an observer in Canada.

He died in an accidental plane collision during a training flight in Scotland on 17th December 1941.

He is buried in Chichester Cemetery and his grave has the inscription ‘In remembrance of Dick.’

He left behind a young widow- Lydia Sophia Cutten and his funeral was also attended by four siblings all in uniform- two sisters in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), one in the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) and a younger brother in the Air Transport Command (ATC).

It is often acknowledged that wars bring cruel twists of fate to those who least deserve it.

In 1940 Goldsmiths’ College’s second Warden Tommy Raymont was living out his senior years in happy retirement at Carbis Bay in Cornwall.

The disaster of the British Expeditionary Force’s chaotic retreat to Dunkirk also brought the terrible news that he would outlive his beloved son Major Oliver Thomas Morton Raymont of the Royal Welch Fusiliers.

Major Raymont was 31 years old, had read history at Oxford University and decided to pursue a career in the regular army. He was killed leading a company of the First Battalion in short and fierce battles during the German invasion of Belgium and France and died from his wounds on the 16th May 1940.

In the family he was known as ‘Tony’ and used the forename Morton for formal purposes. He was born in Lewisham in 1909 four years after his father had taken on the role of Vice Principal for men students. He went to Bickley Park School in Bromley and would have been known to the College community when accompanying his father and mother Christine there until Warden Raymont retired in 1927.

The family always had the highest hopes for him and this is reflected in the inscription on his gravestone at the Heverlee War Cemetery in Belgium: ‘Our High Hope.’ Understandably, they were inconsolable. Tommy Raymont had also lost a nephew, 26 year old Lieutenant William Clifton Raymont of the 5th Battalion South Wales Borderers, who was killed in action in 1917.

Men of the 1st Battalion Welch Fusiliers and Major Oliver Raymont [not in picture] celebrate St David’s Day, 1 March 1940. By Keating (Lt), War Office official photographer. IWM Non Commercial Licence

Against a constant background of antisemitism throughout the 20th century a violent pogrom broke out on the 1st June 1941 in Baghdad following the collapse of Rashid Ali al-Gaylani’s pro-Axis coup d’état earlier that year. It was called the Farhud (‘violent dispossession’) and approximately 200 Iraqi Jews were murdered though some sources put the figure as much higher. Up to 2,000 were injured.

Judaism in Iraq, Mass grave of victims of the Farhud, 1941. Scanning of a page from the book ‘Iraq’ (edited by Haim Saadoun), published by the Ministry of Education and the Ben – Zvi, Jerusalem, (5762, 2002) page 17. Public Domain.

Future developments in the Middle East, including the establishment of the State of Israel, led to further persecutions and contributed to a combination of expulsion and flight. Over 400,000 Israelis are of Iraqi-Jewish descent.

Salim Nakar, Naim Basri, Reuben Dabby and Ezrah Somekh were sponsored by the Anglo-Jewish Association. Salim was born in Iraq in 1913 and educated at the famous Shamash Jewish High School in Baghdad before arriving in London to start studying at Goldsmiths on 21st September 1937.

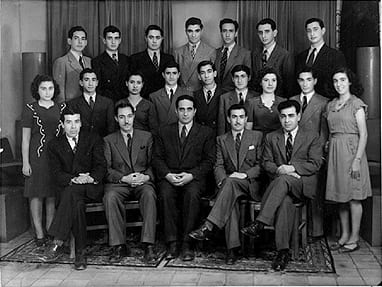

The graduating class of the Shamash High School with their teachers, Baghdad, Iraq 1947. Beth Hatefutsoth Photo Archive, courtesy of Naim Dangoor, Israel.

Shamash had an enrolment of 900 in 1939, but Salim would not return to Iraq to pursue his career as a teacher. After the violent events in that country and the Middle East, the school would close in 1951.

Salim Ezra Jacob-Nakar stayed in Britain to complete a University of London science degree and Teacher’s Diploma in 1942. He had moved to Nottingham with Goldsmiths in 1939 to continue his studies. He would take British citizenship while working as a science teacher in Leicester in 1947, marry Cecilia Gaus in 1949 and move back to work and live in South East London.

Salim Ezra Jacob-Nakar, an Iraqi born Jewish student, is student number 19, second standing from the left in this picture of his student group during his first academic year at Goldsmiths between 1937 and 1938. Image: Goldsmiths Archives and Special Collections. All rights reserved.

Naim Hesel (Israel) Basri was born in Iraq in 1912 and arrived in London in November 1937 to study at Goldsmiths’ College in New Cross eventually qualifying as a physical education teacher in July 1939.

His teaching career in Britain started immediately. He would marry Seraphine Embarchi in the City of London in 1945 and passed away in Westminster in 1971 leaving probate of £20,597 which has a value of £359,025.03 as of 13th November 2023.

Naim Nasri, an Iraqi-born Jewish student, is seen lying on the grass on the right in the 3rd year special Physical Education instructor course group at Goldsmiths in 1939. Image: Goldsmiths Archives and Special Collections. All rights reserved.

Reuben Ephraim Dabby was 26 and Ezra Somekh was 24 when they took part in the evacuation with Goldsmiths’ College students and staff to University College, Nottingham in 1939. They lived together in the same ‘student digs’- two rooms in Ernest and Margaret Seaton’s home at 49 Highfield Road, Nottingham.

Ernest was a dustman working for the Nottingham Corporation. Reuben and Ezra were determind to complete external University of London degrees as private students and this they would do with outstanding outcomes.

Reuben earned a first-class degree in Chemistry and his achievement was announced on the front page of the Nottingham Evening Post on 17th August 1942.

As with Naim Basri and Salim Nakar, they would both settle in Britain. Reuben married Margaret Olofsky in Stepney East London in 1949. He lived a long and successful life and passed away in Enfield in 2004.

Ezra Somekh gained a University of London Physics degree in August 1941, married Leslie Loewenthal in Nottingham in 1943, was appointed to his first job as a teacher in the city and took British citizenship in 1947.

He taught physics and was head of swimming at Nottingham High School, and in 1955 was appointed Senior Physics Master at Burton Grammar School. He was also an enthusiastic photographer winning prizes in competitions.

His teaching at Burton inspired his pupils to achieve record examination results and scholarships to Oxford and Cambridge and is celebrated by the school in its history of the period. He wrote the influential textbook Practical Physics for Chatto & Windus in 1965 and eventually became a chief A-Level examiner. He would also organise yearly sixth form trips to London in order to ‘cross the big divide’ between London and the regions.

V2 destruction in London in November 1944. Image: War Illustrated. For the first few weeks Britain’s war-time government tried to keep the arrival of the deadly terror missiles a secret by claiming unexplained and massive blasts had been caused by exploding gas-mains. The public guessed and knew differently and the running joke about ‘flying gas-mains’ took hold.

Those living and working in London during the Blitz experienced a special intensity where the margin between life and death was a mere thread of time, place and luck.

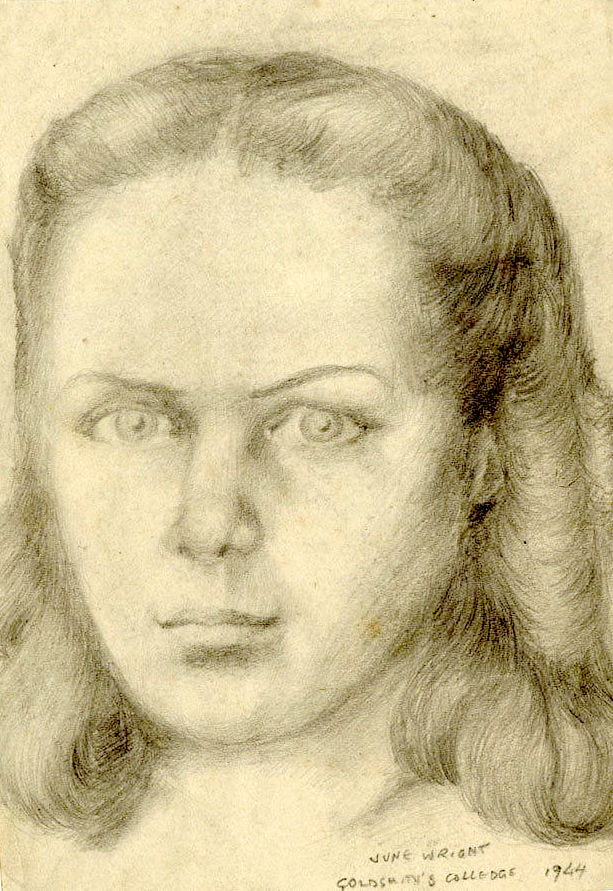

The Goldsmiths History Project acquired a quite haunting sketch by Goldsmiths art student Graham Coton.

In 1944 he drew a young woman called June Wright. She too would have been the same age- perhaps eighteen or nineteen.

Portrait of June Wright by Graham Coton at Goldsmiths’ College School of Art 1944. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

Graham Coton (1926-2003) would become one of the country’s leading graphical artists, and was perhaps best known for his work with Amalgamated Press in World War II comics such as Kit Carson, Sexton Blake, Master Spy, and Captain Phantom.

The provenance of this original graphite drawing from 1944 states that June Wright: ‘was a friend of both Graham and his wife Beryl who met as students at Goldsmiths’ and that she died in one of the bombings of that year.

There is a phantom resonance to this sketch because her name does not match any of the civilian victims of the Second World War recorded by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, and it is something of a challenge to corroborate her very existence.

Perhaps her real name was different. What cannot be denied is that her bright and piercing eyes and somewhat foreboding countenance stands as a symbolic portrait for the thousands of young women in Britain whose lives were so cruelly cut short by the war eighty years ago.

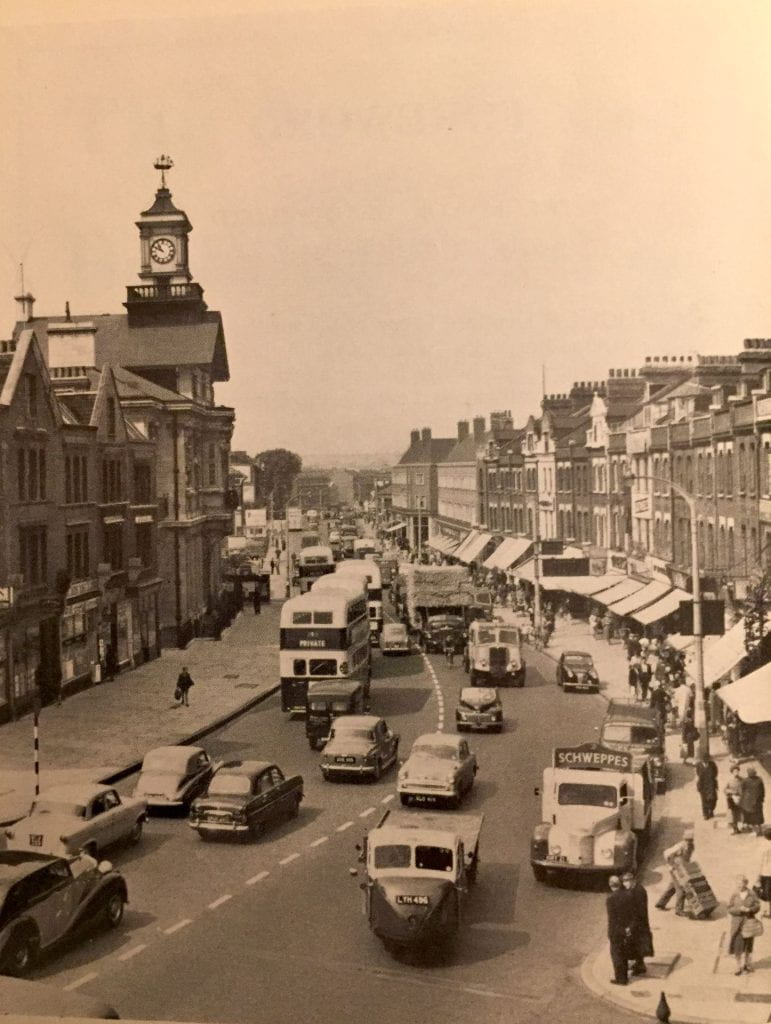

And the community around Goldsmiths would witness the highest number of civilian casualties, many of them young women like June Wright, from a V2 rocket bomb which descended from the sky on the Woolworths and Coop stores in the New Cross Road Saturday lunch-time 25th November 1944.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

Much has been written about an event which tore the heart out of the local community; largely because so many women and children died. Norman Longmate in his book Hitler’s Rockets: The Story of the V2s devotes pages 207 to 212 to a detailed description and analysis along with eye-witness accounts.

But there is little evidence now of what happened either by way of commemoration to those who died or tribute to those who took part in the rescue operation. Lewisham Council Local History and Archives Centre lists the details of those who died and could be identified. It seems 23 could not.

Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

There are plaques which briefly state ‘In memory of the 168 people who died and those injured in the V2 rocket attack that landed here 25th November 1944.’

This had been the 251st V2 rocket successfully launched into Britain and counted as one of the worst civilian disasters of the Second World War.

People died in the pancaked Woolworths store and Coop next door.

An army lorry was overturned and destroyed and everyone sitting in the number 53 double decker bus and those at the bus queue were struck down.

Debris stretched from Deptford Town Hall to New Cross Gate station and it took three days to retrieve all the casualties.

Mrs Barbara Smith told the BBC’s WW2 People’s War Project:

‘One Saturday morning I was visiting a friend near my home. As I arrived at her door, a V2 fell. I said to her, “I must hurry home, that was a V2.” It had fallen at the bottom of my road on the Woolworths store in New Cross. As I hurried home I saw many people who were injured, and others were dead and lying on the pavements and in the road. Ambulances and fire engines were parked nearby, attending to the injured and dying. The air was filled with grit and dust. There was a huge crater on the Woolworth site where the V2 had fallen.

The first four houses in my road [Goodwood Road] were demolished. We were number 9 and my house was badly damaged, a four storey Victorian house, but it was still standing. The tall flight of front steps were damaged, windows fallen out, ceilings down, furniture damaged. How thankful I was that my family was alive and only slightly injured. Unfortunately the dog was missing. She had run out when the V2 fell.

I had been at the Woolworths store visiting every Saturday morning with a friend, but that particular Saturday, I’m glad to say that I hadn’t gone.’

St James’s Church is the nearest to the location of the disaster. The church as it was has been acquired by Goldsmiths College and turned into an art gallery and teaching rooms.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

A new church building is situated nearby. Again the memorial to Deptford’s fallen in the Great War is in tablet form with names inscribed.

The victims of the Blitz in the Second World War are memorialised by an open stone book on a plinth and a garden has been planted in memory.

By 25th November 1944 the media were no longer fully shackled by censorship. Even the BBC’s Audrey Russell was sent to the scene to record interviews and make a voiced report though the acetate discs of her work have not survived and the recordings seemingly never broadcast at the time.

War Illustrated used graphics in a publication in late December 1944 to explain how the V2 rocket was fired some 60 to 70 miles into the sky and came down from space at 2,000 miles an hour.

The rescue and salvage operation was among the biggest to be mounted in London. 100 National Fire Servicemen attended, including George Roberts from New Cross, multiple cranes, and heavy and light rescue squads from Deptford and surrounding boroughs.

The entire First Aid Post operation headed by Dr. Knight and situated in purpose built headquarters at Barriedale to the north side of the Goldsmiths College grounds coordinated the emergency medical services.

By Monday 27th November national newspapers published reports though still avoiding any identification of the specific location.

The News Chronicle‘s headline was ‘Bomb In Crowded Street Killed Women Shoppers- Chain Store Was Demolished.’

“Women and children, busy about their shopping were killed recently when a bomb fell in a crowded street in Southern England. Dead and injured were scattered about the roadway.

A chain store, which was one of two shops demolished, and another large store, which was badly damaged, were filled with customers, mostly women and children.

A large proportion of the fatal casualties occurred in those two shops and in the road outside, where a passing bus was wrecked.

Fire in the ruins hindered the rescue squads, who toiled through the night, clearing wreckage with the aid of cranes.

Thirty hours after the bomb had fallen bodies were still being brought out of the ruins.

Apart from those killed or seriously injured, many received minor injuries from flying glass and falling masonry.

Mrs Bessie Payne, who occupied a flat over the badly damaged store, with her five-year-old daughter Beryl, was buried.

“I was in the kitchen,” she said, “when the walls collapsed and the ceiling fell on me.

“I was buried almost up to the neck, but by wriggling violently I managed to free myself. Then I hunted through the choking dust until I heard Beryl crying.

“She was nearly buried, but I managed to free her. I have lost everything, but I am lucky to be alive and to have Beryl safe.”

The Daily Mirror‘s front page headline was ‘Bomb Hits Stores’:

“Through a winter afternoon and night and on into the following morning grim-faced men kept toiling to release women and children believed to be buried in the debris of a multiple store in Southern England hit by a V-bomb recently.

The bomb fell when the shop was crowded with mothers and children, many of them doing their Christmas buying. Fatal casualties were numerous, and many injured were taken to hsopital.

The same bomb also wrecked another store and families had to be rescued from the explosion-stripped skeletons of their homes facing the store.

Women queuing outside a fish shop nearby were swept over by the blast.

Twenty hours after the bomb fell, rescue squads were still digging in the glare of mobile lighting units.

Red-eyed rescue men who had been working furiously for fourteen hours dug with renewed speed as a woman’s voice drifted up through the debris. She was dead when, later in the afternoon, they got her out.

The crater left by a V2 bombing in London at the end of 1944. Image: War Illustrated.

Two cranes pulled away girders and raised giant buckets of debris, uncovering the last remaining victims amidst crushed saucepans and household goods which the women had been examining when death struck.

Near the rescuers, treated almost with reverence by the grimy men, lay a pathetic little pile of children’s fairy stories, nursery rhymes and painting books.”

The Daily Express reported:

“Ambulances stood silently by as rescuers worked with hydraulic cranes. Nearby lay a little pile of children’s fairy stories, nursery rhymes and painting books. Beside them, salvaged intact, were rows of tumblers, bottles of lemon squash, tins of evaporated milk, packets of envelopes and assistants’ invoice books. Price cards were scattered over the road and trodden underfoot.”

Another dramatic eye witness account was provided to the TimeReel ITN documentary London’s War: The Road To Victory in 2010:

“I remember seeing a horse’s head laying in the gutter. And further on, there was a pram hood all twisted and bent.

And there was a little baby’s hands still in its woolly sleeve. Outside the pub, there was a bus. And it had been concertinaed. Rows of people were sitting inside all covered in dust and were all dead.

I looked over to where Woolworths had been, and there was nothing. There was an enormous gap, clouds of dust and I could see right through to streets beyond.

But there was no building; just piles of rubble and bricks. The only thing still standing was the Coop. And it was still settling.

And the rubble and debris was still settling down and from underneath all that, I could hear people screaming.”

Images of the destruction and aftermath have been archived by Lewisham Council.

These include a view of the wrecked houses on the corner of New Cross Road and St James’s.

Then there is the view of the obliterated Woolworths store on New Cross Road, what is left of the Coop and being able to see through to Batavia Road.

A few days after the debris clearance the photograph below provides an open view from half way down Goodwood Road to Deptford Town Hall. The entire corner of Goodwood Road and New Cross Road has been flattened. Three huge metal containers are on the roadside which had been used by heavy cranes to clear most of the rubble.

The devasation and salvage operation after the V2 rocket attack on the New Cross Road 25th November 1945. Image courtesy of Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre.

Another photograph shows the devastation and destruction from Batavia Road looking across the flattened Woolworths site over New Cross Road towards St James’s with the church in the far distance. A small piece of the shelving from the ground floor premises of Woolworths has survived.

A fifth photograph presents the scene from the Deptford Town Hall side of New Cross Road, with the tramlines in the road, to half of what is left of the Co-operative Society store and looking over to the flattened site of Woolworths and wreckage of houses on the other side of Goodwood Road.

The Mary Evans picture library licences photographs preserved in the London Fire Brigade museum.

There are six high resolution and dramatic pictures of National Fire Servicemen engaged in the rescue operation working in smoke and debris, and these are curated in the site’s search facility under the reference ‘Goodwood Road’.

There are two panoramic daytime scenes in Goodwood Road and New Cross Road showing the heavy lifting cranes and smoke still billowing up from a fire at the back of Woolworths. It can be presumed these were taken on the day after the V2 struck.

The victims and their identification

This is a new work in progress investigating and exploring the ancestry and life traces of each and every one of the people who died in the V2 disaster. These were people who made up the humanity of New Cross and neighbourhood in 1944. They had heritage and families. They had jobs, lived in homes and had futures. They constituted the very heart of the community. They had voices, dreams, hopes, fears and souls. They were and are much more than mere names and statistics.

The plaques and memorials cite 168 people who died. The Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre lists 144 named casualties with ’23 or 24 others who could not be identified.’

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission records names and details for 147 casualties for 25th November 1944 and then provides records of three further deaths in the three days which followed. These were seriously injured victims who died in hospital. One fatality is also located with a place of death at Goodwood Road.

Consequently, 151 named individuals can be listed as victims of the bombing. The issue of a remaining 17 people never being identifiable requires further inquiry. During the London Blitz it was not unknown for people’s bodies to be destroyed by blast and incineration, or indeed, in macabre terms, to be dismembered and mutilated beyond the extent that they were capable of identification.

However, even given the fact we are dealing with forensic pathology of nearly 80 years ago, medical and coroner’s services were usually very skilled in eventually ensuring that every missing person was accounted for.

Where no trace of a missing person’s body could be found, it was law and practice for the Coroner to hold an inquest and issue a verdict as to their fate.

Longmate’s book quotes from a report compiled by ‘the casualty services officer from regional headquarters’ that at Deptford Town Hall ‘an improvised collecting post for casualties and first aid post came into being.’

The V2 rocket detonated at 12.25 p.m. The report states ‘the heavy mobile first-aid unit, in charge of Dr Knight, from Barriedale FAP [First Aid Post] was called at 12.38’ and arrived a few minutes later.

The report also states: ‘The original mortuary having been destroyed, a temporary mortuary was established at the premises of Pearces Signs, to which bodies and fragments of bodies were taken.’

It is not clear which mortuary the report’s author is referring to in terms of ‘having been destroyed.’

The Pearce Signs’ building had been badly damaged and it can be presumed it would have been used as a preliminary collecting point.

Deptford Council had specifically converted the Goldsmiths College swimming pool for the purpose of being used as a mass casualty mortuary. It had been damaged in Blitz incidents, but it was not fully destroyed by fire until May 1945.

Since the Goldsmiths’ College campus was effectively Deptford’s emergency medical services headquarters with the new Barriedale building constructed in the early 1940s to add to the resources, it is possible the converted swimming pool could have been used.

On the other hand the previous damage may have been so great they were forced to find somewhere else to do the distressing work. Such a situation must have been so frustrating and challenging.

To assist with identifying over 100 fatalities additional mortuary staff had also been seconded from Bermondsey and Lewisham.

The researching and writing of the more detailed biographies of the victims and exploring the event in greater depth is being achieved with the separate posting ‘The V2 Woolworths rocket bomb disaster 25th November 1944.’

For the purposes of space this posting presents their names and link to their online Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemoration.

Remembering those who died

23 year old Kathleen Alice Adsley lived with her father Joseph, mother Alice and older brother Edward at 11 St. Norbert Green, Brockley, Lewisham.

16 year old Evelyn Lillian Amos lived with her parents Frederick and Edith at 1 Cranbrook Road, Deptford.

48 year old Frances Ellen Axton (maiden name Shorey) was living with her husband Charles Arthur Axton at 34 Oareborough Road, New Cross.

71 year old Frederick William Bailey like many of those who were killed, resided only a few minutes walk away at 13 Jerningham Road.

42 year old Florence Ethel Banfill died in the rocket attack along with her son who was only three years old. Her husband Bartholomew was left grieving for the loss of his wife and young son. They lived in nearby 19 Childeric Road New Cross.

3 year old Brian John Banfill of 19 Childeric Road New Cross as outlined above died with his mother Florence in this air raid disaster.

30 year old Robert Bass from 84 Douglas Way in Deptford died from the injuries he received in the blast after being taken to the Miller General Hospital in Greenwich High Road.

61 year old John James Bateman was a Police Sub-Inspector assigned to the Air Ministry living at 203 Rochester Way, Blackheath.

74 year old Elizabeth Lillian Jane Beaton was living at 186 New Cross Road at the corner of Pepys Road. She was the widow of William Beaton and originally came from Hampshire.

New Cross Road looking down from the Gaumont cinema towards Deptford Town Hall on the left with the location of the Woolworths V2 attack beyond. Photograph was taken in the middle 1950s. Image: Goldsmiths History Project.

31 year old Harriet Amy Bentley lived at 7 Cambridge Drive in Lee. Harriet was born Harriet Duffy 17th May 1913 and worked as a drapery shop assistant.

51 year old Theodore Ludwig Berning was a married man living at 32 Downhill Road in Catford. He had been born and brought up in London’s East End Jewish community starting out his working life in 1911 as a salesman at the age of 17.

60 year old William John Bradford had been living with his wife Catherine at 6 Headley Street, Peckham. The house and street no longer exist.

Post WW2 map of Goldsmiths’ College in Deptford showing the locations of the College, Deptford Town Hall and V2 rocket attack. Image: Goldsmiths History Project

37 year old Florence Elizabeth Harriet Branscombe was living with her mother Elizabeth Branscombe at 9 Raymouth Road, Rotherhithe.

67 year old James Henry Bradon was the husband of Louise May Bradon and they both lived at number 42 Comerford Road in Deptford. The terraced Victorian house is still very much looking on the outside as it was in 1944.

65 year old Andrew Poulton Brazier was living with his 72 year old wife Elizabeth at 43 Manor Avenue, Brockley which at the end of September 1939 had multiple occupancy. Public documents show his actual age was 67 as he was born 24th October 1877.

6 year old Nicholas Oliver Bright was the only son of George, 49 and Grace Bright, 47, who were living at number 44 Peckham Hill Street, Peckham. Their house is no longer standing and is the site of a Burger King fast food restaurant.

31 year old Ivy Brown lived at 48 Evelina Road, Nunhead with her husband George Henry Brown. They married in 1941. It seems Ivy was shopping either in Woolworths or the Coop with her 18 month old daughter Joyce who was also killed in the V2 bombing.

18 month old Joyce Brown was the daughter of Ivy Brown who died in the same incident and is profiled above.

12 year old Sylvia Rosina Brown was the younger daughter of 43 year old Albert John and 41 year old Lilian Gertrude Brown, and they lived at 56 Oareborough Road in Deptford.

40 year old Maud Alice Bush of 27 Pepys Road, New Cross Gate, Deptford was the daughter of Henry Bush. She was critically injured in the V2 explosion and taken to the Miller Hospital in Greenwich but died from her injuries on the same day.

44 year old Reginald Bradford Calder had a dramatic and adventurous life. At the time of his death he was living with his 42 year old wife Violet Hagen Calder and two daughters at Greenways, The Glen, Farnborough Park, near Orpington in Kent.

21 year old Doris Eileen Edith Card worked for the British Red Cross Society during World War Two.

26 year old Mary Josephine Carroll was an Irish woman living at 24 Girton Road, in Sydenham, Kent. She was the daughter of James and Norah Carroll, of 15 St. Laurence’s Terrace, Lower Grange, Waterford, in the Irish Republic.