Nigel Perkins in the third floor studio of the Blomfield building of Goldsmiths, University of London in 1996. Image by kind permission of Paulo Catrica.

Lecturer Nigel Perkins passed away from COVID in January 2021 after a brilliant career lasting forty one years teaching photography and image communication in the Department of Media, Communications and Cultural Studies.

The postgraduate MA he convened, now called ‘Photography: The Image & Electronic Arts’ has been one of Goldsmiths’ most successful.

Nigel can be credited with producing more than forty cohorts of students from all around the world who have had outstanding careers as artists, photographers, and influencers in all spheres of culture, media, and academia.

He should also be remembered fighting for and preserving film making at Goldsmiths when in the 1980s the pressure to focus on television and media theory threatened its extinction.

The story of Nigel at Goldsmiths is the story of advancing and sustaining the arts in university media and the wider cultural industries.

The powerful expression of tributes from past and present staff and students in the days following his death provides a significant document about the purpose and value of the arts and humanities in university teaching.

It is clear he was a legend and inspiration.

Significance in Goldsmiths History

Nigel’s time and contribution to the history of Goldsmiths is also symbolic of what has happened in British society and culture over four decades.

From 1980 to 2020 we have journeyed from the analogue world of typewriters, filing cabinets, darkrooms, film cameras and petrol cars to the digital information age of virtual online reality, robotics, artificial intelligence and electric vehicles.

It is the difference between 1905- when cars looked like stagecoaches without horses, the Wright brothers were experimenting with early aeroplanes that had the appearence of curtains strung across climbing frames, an artillary shell needed firing from a howitzer to displace a basement of earth- and 1945 when silver metallic B29 multi-engined bombers could drop atomic bombs and annihilate whole cities, and racing cars looked like imaginary flying saucers with four wheels and the aerodynamics of a bullet.

- The front car park of Goldsmiths, University of London during the 1980s. Image: Goldsmiths Archives.

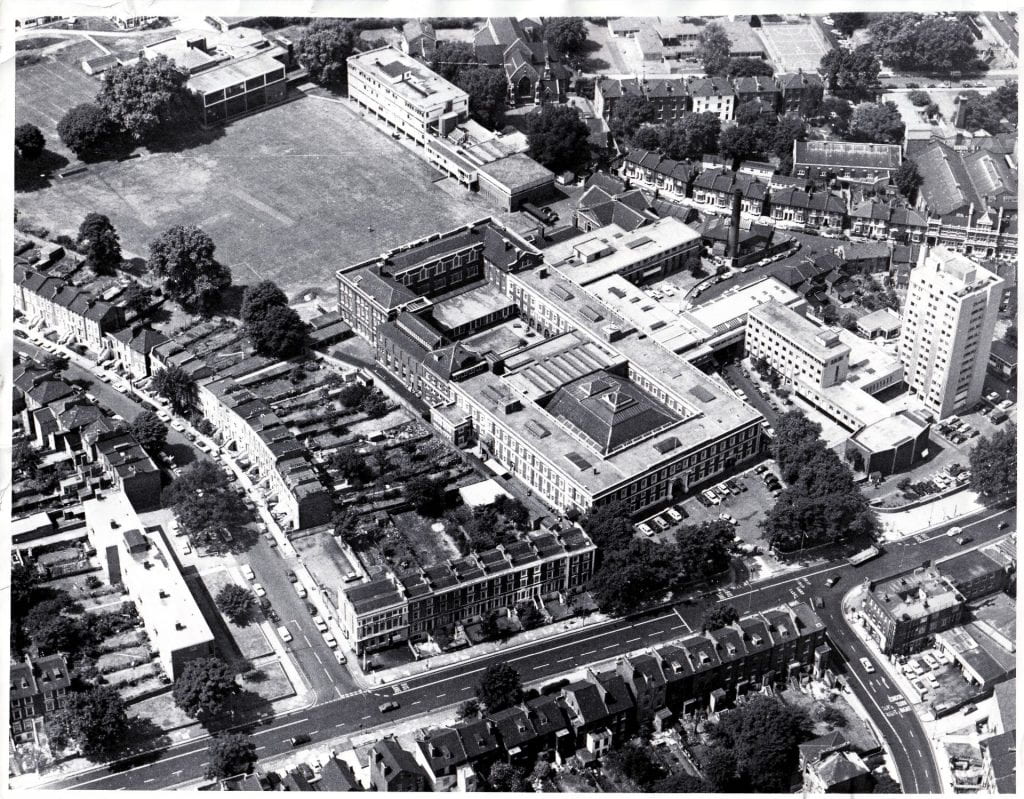

- Aerial view of Goldsmiths in black and white late 1970s. No library building or Professor Stuart Hall complex behind the back field. Image: Goldsmiths Archives.

- Aerial view of Goldsmiths around 1980 in colour. Just possible to make out the parked vehicles at the front of the main buiilding. Image: Goldsmiths Archives.

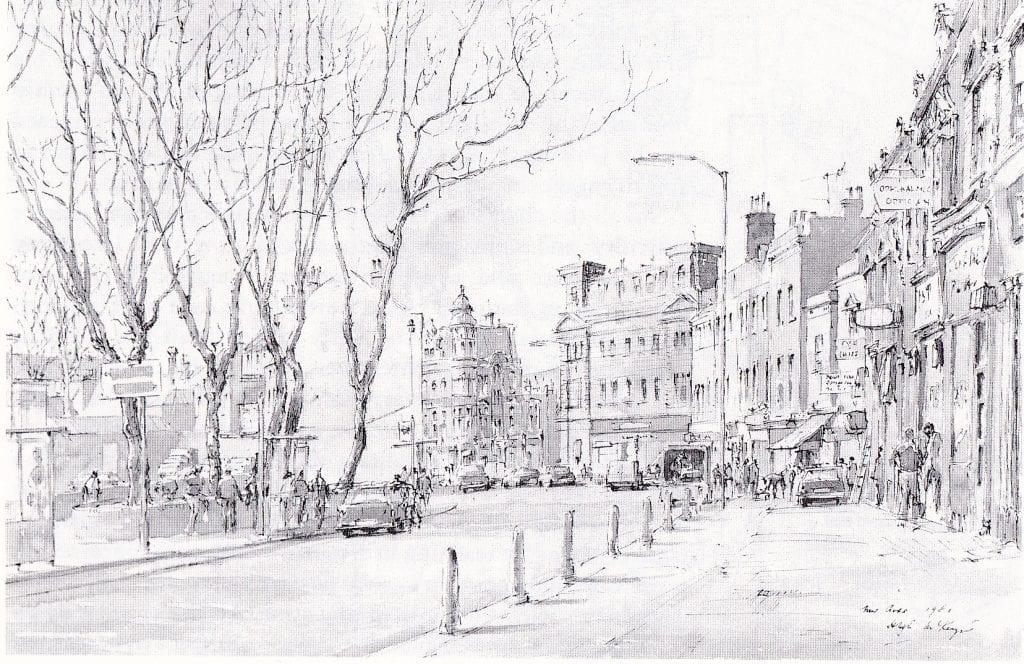

- New Cross 1981 by H. Mackenzie. Watercolour in Goldsmiths Art Collection. This view is from the position of Sainsburys and Costa Coffee in 2021. Image: Goldsmiths Archives.

At Goldsmiths in 1980 the site of the glass fronted Professor Stuart Hall Building with its digital photolabs, film, television, sound studios and multi-media laboratories was merely a grassy promontory dotted about with a dilapidated portakabin or two, and a ‘pottery’ for ceramics.

Cars were parked in front of what is now called the Richard Hoggart main building on Lewisham Way.

And Richard Hoggart as Goldsmiths’ Warden was struggling to save the College from oblivion.

Goldsmiths was not even a ‘school’ of the University of London, its degrees had to be validated elsewhere, its lecturers had to be ‘recognised’ at Senate House in Bloomsbury before they were allowed to lecture on any University of London degree course, and there were no Goldsmiths’ appointed Professors.

‘Chairs’ had to be sponsored- one by the London Borough of Lewisham; the other by the Institute of Education.

Goldsmiths had an apostrophe and came after ‘University of London’ and the comma.

It was a hotchpotch of Art School, Teacher Training College- the biggest in the country, and Adult Evening Institute.

Money was so tight staff were told to only use the phones after 1 p.m. to take advantage of the cheaper call-out rate.

Staff Bulletin from Goldsmiths in January 1980 with message from Warden Richard Hoggart reporting on earnest efforts to gain School of University of London status. Image: Goldsmiths Archives.

This was only a few years after the National Front had been repulsed at the Battle of Lewisham, and a matter of months after Margaret Thatcher’s monetarist Conservative government had been elected by a landslide to cure inflation with unemployment and recession.

Goldsmiths’ School of Art had been ‘exiled’ to the Millard building in Camberwell, formerly St Gabriel’s Teacher Training college and gobbled up in a merger when the government decided the country’s schools needed fewer teachers.

But in the process Goldsmiths had gained a building and a Picasso and Constable for its Art Collection.

New Wave- ‘Godard has lost his greatest fan.’

Into this cauldron of chaos and desperation the photographer and film-maker Nigel Perkins arrived with his characteristic turtle-neck sweaters and the elan of somebody who had just finished working on a Jean-Luc Godard or Luchino Visconti film.

Nigel was New Wave. His mother gave birth to him in the spring of 1948 after Great Britain’s worst winter of the 20th century and in a society very much marked by the austerity of post-war rationing.

He learned his art and crafts in the counter-culture age of 1960s Chelsea and his photographic and performance gigs connected with Paul McCartney, Ginger Baker, and Art House movies.

Creative courage, experimentation and free-thinking drove his adventures.

He applied his lens to the image as boldly as his ancestor Horatio Nelson played risk and chance with sail and cannon ball.

In the academic year 1979-80 the Department of Visual Communication had gained a lecturer with the looks and style of Paul Newman in the part of the racing car driver in the 1969 film Winning, or Steve McQueen on motocycle in The Great Escape (1963) and car chasing and racing in Bullitt (1968), Grand Prix (1966) and Le Mans (1971).

The idea of his involvement in motor-racing is not at all fanciful.

He told his colleague Arnold Borgerth and others that he had indeed been a racing driver at some point. He was about to sign a contract as a professional driver with the Jaguar team, but decided he did not want to dedicate his life to that world and left the car racing circuit.

And it is some irony another colleague, Professor Colin Gale, recalls that in the early 1980s it would be a Citroën Dyane parked outside his studio in the more run-down part of Chelsea; not Jensen, Aston Martin, Ferrari, or even Jaguar.

At the same time Nigel was a gentle and friendly mentor and teacher. He would talk and converse softly and offer his enthusiasm and care to every student.

On hearing of his passing his colleague Dr. John Hampson said:

“I shall miss our very long talks on anything and everything. Godard has lost his greatest fan.”

Jean-Luc Godard at Berkeley, 1968 notable for the films Breathless, My Life to Live, Contempt, Pierrot le Fou and A Woman Is a Woman. Image by Guy Stevens. CC BY 2.0

‘Something Zen about him’

Professor James Curran joined Goldsmiths as Head of the Department of Visual Communication in September 1983 and remembers Nigel as embodying ‘the free thinking, warm, art house tradition of the old Goldsmiths that we must cling on to.’

“I admired the way he combined an active dual life as an artist and inspirational teacher. The quality of his teaching was reflected in the stunning exhibitions of his students in the summer term – displayed year after year.”

James says ‘There was also something Zen about him. He was totally without ambition. He was just happy in what he did, and he did not want to change it. He was a person untarnished and undiminished by the neoliberal times in which we live.’

“As a person he was warm, boundlessly enthusiastic, idealistic, and empathetic.”

James believes Nigel Perkins was also the product of the early 1970s indie moment which shaped him.

He felt there was ‘also something quite old-fashioned about him – from the location of his studio to the way that for over 35 years he always sent me a Christmas card, signed Nigel P with an engaging and almost indecipherable note beneath it.’

“He belonged to a time when our department was small, and we really knew our colleagues and our students. His death symbolises a larger loss. But what I retain above all is the memory that he was a sweet man.”

Reunion of the class of 1996-97- ‘One of the best teachers I ever had in my life’

In September 2019 Head of Exhibitions at The Photographers’ Gallery, Clare Grafik, proposed a reunion of the Image and Communication class of 1996-1997 at her place in London. Students of that particular year convened from all corners of the world to celebrate what they described as their ‘incredible year in Goldsmiths.’

The architect, photographic artist and academic Dr. Yiorgis Yerolymbos flew in from Athens.

Yiorgis had never forgotten that ‘Nigel was one of the best teachers I ever had in my life. He taught me qualities that I still follow in photography, my profession by choice as well as on life itself.’

“He was the first person I met in college, London or the UK for that matter. He welcomed me the very first day and was eager to establish contact, although at the time, I have to admit I was not fluent in English. He didn’t mind, he was patient with me, he gave me time and space to gradually find the way to express myself.”

Yiorgis remembered that during their brief encounter in September 2019: ‘he revisited every single student project we produced that year almost two decades ago. He talked in detail about our original as well as our final projects that formed the graduating exhibition. He even remembered the interim stages each and every one of us explored and rejected.’

Yiorgis and those at the reunion recall that ‘Along with Ian Jeffrey they formed an incredible duo that worked as crossfire during tutorials, the practitioner and the theoretician leaving nothing out of sight or discussion.’

Ian Jeffrey (left) and Nigel Perkins (right) during reunion of class of 1996-97 in September 2019. Image: kind permission of Dr. Yiorgis Yerolymbos.

Yiorgis added: ‘A tutorial with them meant you had to enter in that room really well prepared otherwise you would face the consequences.’

“To this day I never forgot that lesson; I still prepare myself to the last detail I possibly can before entering a professional meeting or a lecture in front of an audience. I vividly remember him telling me exactly that, “next chapters in life can prove to be quite a challenge so I need to make certain you know how to handle yourself.”‘

Dr. Yerolymbos gave permission for his tribute to Nigel Perkins to be read out in full by Professor Natalie Fenton at the first Departmental meeting following the news of his death.

More than 60 members of staff heard that ‘Nigel was nothing but a positive influence on me, his presence shaped my life to a large extent ever since I met him some twenty-one years ago.’

“During the brief time I myself taught in the university in my home country I implemented his guidelines and style bringing out incredible responses from the students. Twice during my MA in Goldsmiths I produced work that was above average but nothing more, it would just suffice to get my degree. Both times Nigel assured me “that is quite all right, you can leave it there… if you choose to. But are you sure you want to stop there?” Those words triggered me to go back and start again in order to get a better result, and I have to admit I copied his method down the line.”

Yiorgis recalled that he ‘always considered Nigel as a tutor that could greatly affect any student, whatever their ethnic background, nationality, colour or belief system. He could motivate not only the hard working students but also the not so much. In the end we all wanted Nigel to think highly of us. He did that with grace and wit.’

It has often been said that teachers are defined by the memories and testimonies of their students. This was certainly true when Yiorgis said:

“Permit me to express my gratitude to my tutor for everything he has done for me, I will remember him as well as his impact in my life. To his family and the people closest to him, your loss is my loss, I extend you my deepest condolences.”

‘During his cancer treatment, he Face-timed me for my tutorial from his hospital bed’

Nigel Perkins supervised lecturer and artist Monalisa Chukwuma during her MRes in Filmmaking, Photography and Electronic Arts at Goldsmiths between 2017 and 2018. He was also one of her supervisors during the first year of her PhD.

She says: ‘Nigel had an extraordinarily unique way of seeing and provided me with tools for dreaming, for thinking and for making art.’

Monalisa is now lecturing at Goldsmiths and she told the staff meeting commemorating Nigel’s contribution that ‘Over the years, I have been moved by the great acts of personal kindness that Nigel showed me’:

“Last year during his cancer treatment, he Face-timed me for my tutorial from his hospital bed. He began by apologising that he couldn’t sit. During the tutorial, he gave me one of his warmest smiles. And he was clever and never referred once to his obvious discomfort.’

Afterwards, I was struck by how much he cared for his students and very sad to see him like that. A few months later before I went for my fieldwork in Nigeria, he asked me to come and see him. He still couldn’t sit for long periods of time. So, he stood for two hours as he showed me clips from several films, which he thought could influence my fieldwork.”

From left to right Nigel Perkins, Yiorgis Yerolymbos, Clare Grafik, Alexandra Moschovi, Anne Christine Jenssen, Ian Jeffrey and Paulo Catrica at the reunion of the class of 1996-7 in September 2019. Images by kind permission of Dr. Yiorgis Yerolymbos.

‘One sensed that he loved mankind as it was, despite itself’

There was consensus throughout the Department from colleagues that the most memorable experience they had of Nigel Perkins was his engaging and welcoming smile.

Monalisa says this was something shared by his students and it was because: ‘One sensed that he loved mankind as it was, despite itself, and that he had little patience for those who followed trends, unnecessary rules, and conventions. As a leader, and teacher, he believed in opportunity, growth, and action.’

Monalisa wanted to emphasise how much of an impact Nigel had on her life in his role as a University lecturer:

‘Many teachers are great, but few capture the imagination and spirit of their students like Nigel. His warmth, devotion and sense of humanity made it easy for him to communicate compellingly to bring forth the best from all his students.

He was a paragon and his influence on my practice and life cannot be denied. I still hear his voice, “Just create work. You don’t have to wait for your ideas to be fully formed. The creative process is research. Examine, question, and test your ideas. Get on with it. Things emerge through making work.”’

Monalisa’s remembrance of Nigel is longlasting and enduring:

“Nothing I say is really adequate to convey my feeling of loss and gratitude to Nigel Perkins. I thank God that I was privileged, to have had this great and vibrant man as my teacher, my mentor, and my friend. They say that history is a living thing that never dies. A life given in service to others never dies.”

Art School ethos

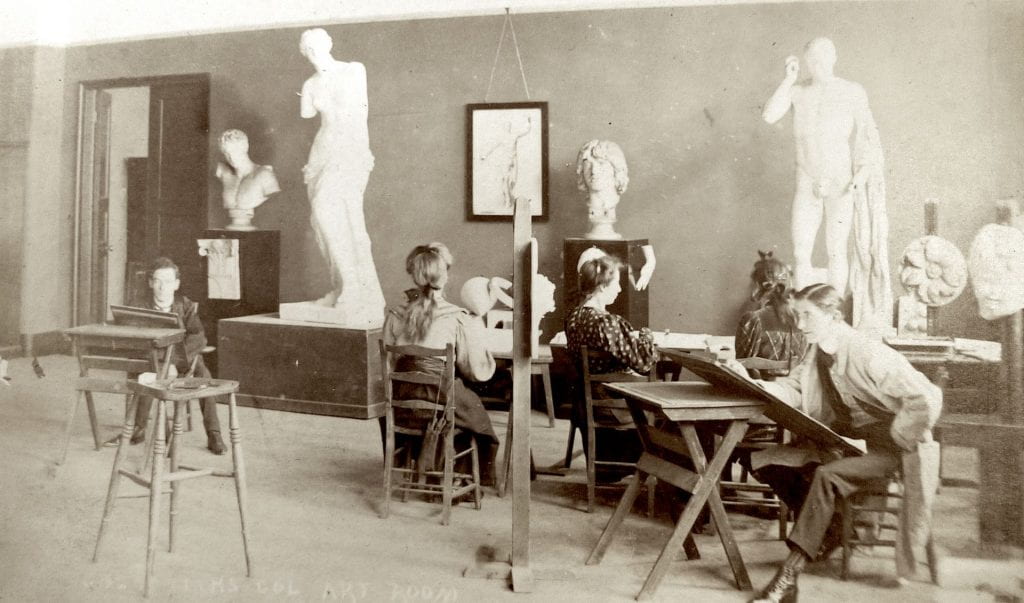

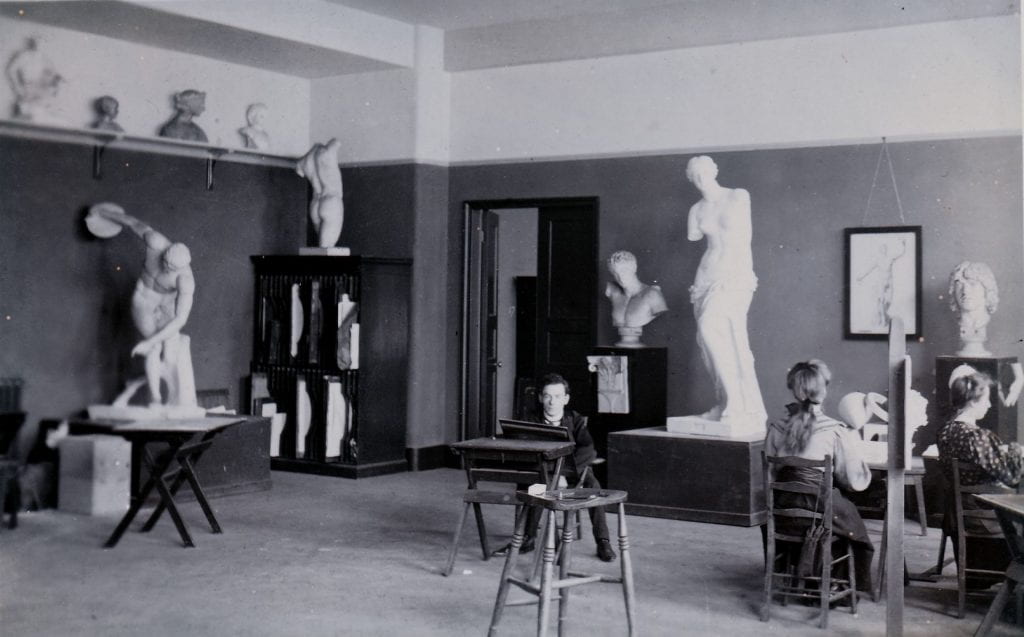

For many years Nigel taught photography in a high ceilinged studio on the third floor of the Blomfield building, constructed specially for the School of Art in 1908.

This is where early Goldsmiths’ College painters and engravers used statues and statuettes as models.

The photography and image communication team were creating in the same space where Graham Sutherland (1903–1980) had been introduced to post-impressionism, where Betty Swanwick (1915-1989) and Clive Gardiner (1891-1960) defied the Blitz during the Second World War to keep on the art teaching during the day while the rest of Goldsmiths was bombed by high explosive and burned by incendiary.

The great African modernist Ben Enwonwu (1917-1994) had sketched and painted in these very same interiors at this time.

Quentin Crisp (1908-1999) was a frequent visitor during the 1940s as a life model. In 1944 he held his pose and poise during an air-raid while the students fled to the shelters.

A doodlebug descended nearby blowing out some of the windows.

When everyone returned they found that Quentin had remained as they had left him so they could resume their sketching.

- Art students at Goldsmiths sketching in a studio of the Blomfield Building in 1908. Image: Goldsmiths Archives.

- Corridor on third floor of Blomfield Building early 20th century.

- Art students at Goldsmiths’ College 1908. Image: Goldsmiths Archives.

- Goldsmiths Art School classrooms in the Blomfield Building at the back of the current Richard Hoggart Main Building and overlooking the College Green.

Art survived and so did the studios.

While the art of embroidery was still practised next door, Nigel and his colleagues taught photography and built darkrooms by converting offices off the stony Edwardian corridor.

The playwright and current head of Radio, Richard Shannon remembers first working with Nigel in 1990 and second marking ‘the most incredible photographic exhibition’:

“Nigel led me down into a dark basement in Laurie Grove and in the dank and dim light, showed some student work which was really challenging – naked images and religious images I will never forget.”

Nigel faced down the Gradgrind banality of Higher Educational metrics with a charming equanimity that while gently frustrating and sidestepping the hopes and plans of ‘Research Assessment Exercise’, ‘Quality Assurance Agency’ and ‘Skillset Vocationalism,’ always protected the creativity, development and success of his students.

He hardly ever talked about himself. He related to the people and, of course, the students he was speaking to.

The last time anyone can recall his participation in the presentation of his ‘research output’ would have been about a quarter of a century ago.

Nigel showed his 1976 film Justine– currently catalogued by the BFI as ‘A series of non-dramatic tableaux representing scenes from De Sade’s novel.’

The beauty, art and emotional resonance in watching it cast an aesthetic spell over the entire symposium.

All the intellectual angst and emotional migraine of grasping the higher reaches of a national league table in academic and practice research theory drifted therapeutically into the dusk of a summer sunset in south east London.

Nigel has additional credits in the BFI film archive for Lifescreen Calling all Women (1996), Is Ordinary Life Possible? (1986), The View from Industrial Britain (1983) and Sympathy and the Hero in His Incredible Isolation (1980).

The Studio Workshop- ‘Common sense is quite often not held in common’

Monalisa Chukwuma has held onto Nigel’s maxim on the artistic implications of common sense.

If he was the Merlin of art in media and communication, he was also its wizard in teaching technique.

He had no objection to the University edict that teaching needed to be ‘peer-reviewed’ and I once had the privilege of sitting in on one of his workshops with third year undergraduates.

There was no document setting out the lesson plan.

‘Aims and objectives’ had not been bullet-pointed and ‘learning outcomes’ were suitably absent from the tick-box grid of surveillance and verification of ‘standards.’

What unfolded before me was a calm, stimulating, and very precisely thought-out creative exchange of questions, suggestions and enthusiastic conversation about the student projects.

Dr Alexandra Moschovi is now a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, and is so very well placed to explain why Nigel was a ‘spirited and inspirational teacher’:

“I remember fondly our tutorials and animated discussions about art, photography, and life. While Nigel was an empathetic listener and a caring tutor, he used a tailored ‘Socratic’ method to get us all out of our comfort zone and think outside the box in the journey of becoming independent and resilient, reflective practitioners. His tutelage had a transformative effect on my creative practice and future career.

It may have been that at the dawn of the digital revolution, I could not fully grasp the potential and subtleties of media convergence that Nigel was talking about, but by encouraging me to experiment with new media, he opened new areas of discourse and practice. What is more, in the course of my academic career, I adopted and adapted some of Nigel’s learning and teaching methods and working philosophy as a programme leader: to concentrate on people and the things that matter most.”

Another former student and present College deputy principal is the photographic artist Kerim Aytac.

He has written about the Image and Communication M.A at Goldsmiths being set up by Nigel Perkins ‘as a kind of rescue action for people in positions like the one I was in’:

“The cohort was mainly talented artists who hadn’t, for whatever reason, had the space to develop themselves. It was a second chance for those seeking to develop their creative potential. Output was mainly photographic but there was video and interactive work also. What really distinguished this course from others was a really light touch approach to project work and much stronger emphasis on creative exploration that didn’t need to be justified critically or historically.

We were encouraged to follow paths that may not have resulted in original work per se, but were instrumental in developing our practice. I loved every minute of it and believe, truly, that I would not be an artist today had I not attended. At that time, Ian Jeffrey, noted Photographic historian and writer, was a tutor on the course and was very influential on my practice. He was very encouraging and turned me onto Japanese photographers like Moriyama and Tomatsu, both of whom are big heroes of mine. He also helped me to think of my work as part of universal collaboration in which all artists help and feed off each other.”

‘Teaching as practised on Nigel’s course was maybe more like a prolonged conversation’

Ian Jeffrey is one of the world’s most respected historians of art photography.

He has written some of the most influential books in this field.

Nigel Perkins respected and recognised his importance.

Ian had left Goldsmiths sometime in the 1980s for more fulfilling and successful pastures of research and lecturing.

Nigel later persuaded him to come back on Thursdays to talk to his students and present joint tutorials.

They became an awe-inspiring pedagogical partnership.

- Revisions: An Alternative History of Photography by Ian Jeffrey.

- Bill Brandt edited by Ian Jeffrey.

- All At War: Photography by German soldiers 1939-45 by Ian Jeffrey.

- How To Read A Photograph: Lessons from Master Photographers by Ian Jeffrey

- Shomei Tomatsu by Ian Jeffrey.

- Back cover of Revisions: An Alternative History of Photography by Ian Jeffrey.

Ian recalls those days with admiration and affection:

“We often gave joint tutorials in a room at the top left of the building, quite close to the fabrics dept. The room with some old chairs and two old tables was never cleaned as far as I could see.

The course took place in nooks and crannies. On the back fields there was a clutch of portakabins where people worked on computers. The cabins were cramped and not well ventilated, but as you were talking to one student you could see five or six others at work. It was a sociable and rather over-intimate environment but it gave life to proceedings.

Nigel’s course was a success. It depended almost exclusively on him. He cared for his students and explained things at length to them in tutorials – sometimes at absurd lengths. He had new teaching procedures almost every year – unvetted by anyone in authority.

It was a difficult course to run. An M.A. in Fine Art would have recruited students who were already experienced art makers. Nigel’s intake was much more diverse, and people did need individual attention – and special instruction in some cases. Some were from rigorously taught and drilled courses and needed to break free – that was always a problem.”

Ian recalls that Nigel recruited a small salon of photographic experts in a teaching team which included from 1997 the photographic artist and lecturer Arnold Borgerth-Filho.

Arnold’s international experience of teaching in several colleges and universities between Brazil, Argentina, Portugal and the UK provided a valuable overseas support and complement that enabled students to appreciate complex ironies and transcultural dimensions to photographic art.

Ian says ‘Arnold offered foundational reliability, steadiness and the perspective of a former engineer which enhances the understanding of students coming from varied walks of life.’

This atmosphere and culture of creative teaching and global experience enabled art and artists to develop with confidence, direction and the necessary discipline:

“Nigel needed people around him – as supporters. It wasn’t from the point of view of academic coverage, more a matter of talk and reliability. I knew from my own earlier years in Goldsmiths how important it was to have colleagues who talked. Teaching as practised on Nigel’s course was maybe more like a prolonged conversation. Sometimes at the end of the day Nigel would prolong the conversation by walking to the station with me – or half-way there.

Nigel’s idea of teaching, perhaps unselfconsciously held, took account of companionship. In Nigel’s case I think that the more one spoke to him the more buoyed up he became, the readier, too, for his burdens. Nor was he very judgemental – and would spend a lot of time encouraging even the most modest students. I think that if he had relaxed or slackened his attention the course would have gone under – it depended on his energies, his liveliness and his obvious delight in meeting people, including students.

He never seemed to me to be at all malicious – very equable, even in adversity. There was no sense ever that he was out to impress anyone – I never thought so, anyway. I think he would have put the effort into any group, just for its own sake – old people, children, the disabled. There was no sense of institutional prestige about anything he did. He assumed, I think, that people were out to do their best, and they responded in kind.”

The culture of teaching on Nigel Perkins’ Image and Communication programme defines what is so unique about Goldsmiths.

The eclectic, the diverse, the pluralistic, the surprise and unpredictable, and the open mind tend to be what marks out any creative academy of excellence in educational history. Ian Jeffrey recalls that Nigel identified patterns that suited him and his students:

“His procedures, whatever they were, didn’t really fit with the times which preferred codifications that could be set out on a grid. He did have a way of doing things, and the way could, with thought, be identified. You probably needed a special temperament to carry it out.

He was always at the centre of a world which involved, for example, his ramshackle or untended properties. He noticed stuff on his journeys and the things people wore on the streets of New Cross. He was sharp and able to make connections – always entertaining to be with.”

Ian remembers that he generally kept quiet about his creative life:

“I presumed that he had things under consideration. He was involved with The Active Archive. He had worked for Metallica, the heavy metal group. Nigel, though, was never one for lingering on the past, on any good old days that he had undergone – it was NOW that he was keen on, and he was in a hurry to get to it.”

Nigel’s lack of professional ego means that 21st century googling yields little by way of Wikipedia profile or online curriculum vitae achievements.

He’s referenced in 2008 helping the Goldsmiths Student Union mount an exhibition by the Norwegian artist Andreas Tovan titled ‘Man at his toilet’.

It was described as a raw representation of Tovan’s daily routine.

Tovan said: ‘People who haven’t actively engaged with the socio-political issues of urination might view it as shock-art. It’s not.”

Ian and Nigel wrote the text accompanying the exhibition.

‘Somewhere along the line he had learnt the creative power of disruption’

The respected artist Professor Colin Gale PhD has held the posts of Head of the School of Fashion and Textiles and Director of International Recruitment and Partnerships at Birmingham City University.

BCU had started in the early 19th century as the Birmingham School of Art and its later history is as eccentric, chaotic and dramatic as that of its New Cross London counterpart.

Colin joined the Department of Visual Communication at Goldsmiths in the same year as Nigel.

This was the academic year of 1979-80 and a vicious time to be in Higher Education.

There had been internal warfare, redundancy, and nervous breakdown among the staff.

The pressure from above veered from wanting to transform the department into a centre for media theorists, to working out how and whether to keep and develop media practice at the same time.

Colin recalls:

“The first I properly recollect of Nigel was when I had been run over and crushed by the College as happens to academics once or twice in their careers. I was outdoors probably moping into a coffee when he walked over and empathized. He too had had his run-ins. In a short time we became friends, co-conspirators, seditionists and subversives. We had common cause in being part outsiders and being practitioners.

In the early 1980s Nigel and I found ourselves in a cloaked battle to preserve practice and even more importantly the intellectual standing of practice.

By the second half of the 1980s I was Head of Electronic Graphics and Animation and Nigel Head of Photography and also I think Film. In fact, I think Nigel can be credited with saving film at Goldsmiths. It was when TV was in the ascendant and film in marked decline. Nigel argued eloquently in defence of film and its importance. It survived barely but in a few years the fortunes of film and TV were reversed. Film became all the rage artistically and commercially and used as the best medium to author content for distribution to different formats and markets.”

In 1992-93 Colin and Nigel collaborated and created the MA in Image and Communication drawing together the practices they were responsible for – animation, graphics, photography, film, video shorts, computer graphics – but framing them in an innovative interdisciplinary and theoretical context.

It was most probably the first of its kind in the country. It has certainly become the most successful, never needing to advertise and regularly oversubscribed and over-recruiting for practically every year of its existence.

At the beginning, they had to fight off opposition from Fine Art.

The programme drew from a number of Art School traditions but it was also firmly framed by the professional practice of the disciplines involved:

“So began a number of years teaching together and undertaking many journeys in philosophy, politics, criticism and pragmatism with our students.

I remember spending whole days seeing a succession of students in a tiny room on the third floor with a round window that looked on the College fields. We looked at contact sheets, storyboards, designs and photographs and when necessary we decamped to studios to watch time-based media.

We discussed everything from the appropriateness of models and subjects, to editorial process to technical resolutions. We would have seminars at the end of the day exacting revenge on media sociology and post-modernism and deconstructing over simplifications of practice and meaning to find the personal and meaningful.”

Colin has a clear idea of why Nigel’s philosophy of teaching has been so successful when more managerially minded higher ups may have despaired at what they perceived as ‘disorganisation,’ or ‘vagueness.’

“He had a great facility for flipping things, somewhere along the line he had learnt the creative power of disruption. We once had an East Asian student, a photographer, who shot everything on automatic, resultantly there was no creative space in his process, no opportunity to develop and the student kind of knew it.

Nigel suggested he build a pinhole camera. He did. He then experimented with colour film stock and the results were like looking at the modern world through a Victorian lens and fascinating. On another occasion we had a student whose work was somehow vague. We discussed adding text to nuance lines of interpretation. The final works seemed profound and the external examiner mightily impressed.”

Colin also remembers an understanding of the ‘distinct attitudes that lay behind his creativity.’

They worked together at Goldsmiths when Nigel set up his studio operation and production projects in Chelsea. Goldsmiths art school luminaries of the past, such as Clive Gardiner, Evelyn Gibbs and even the first ‘Headmaster’ of the Art School in the original Goldsmiths Institute from 1891, Frederick Marriott, had been part of the Chelsea community and tradition of artists.

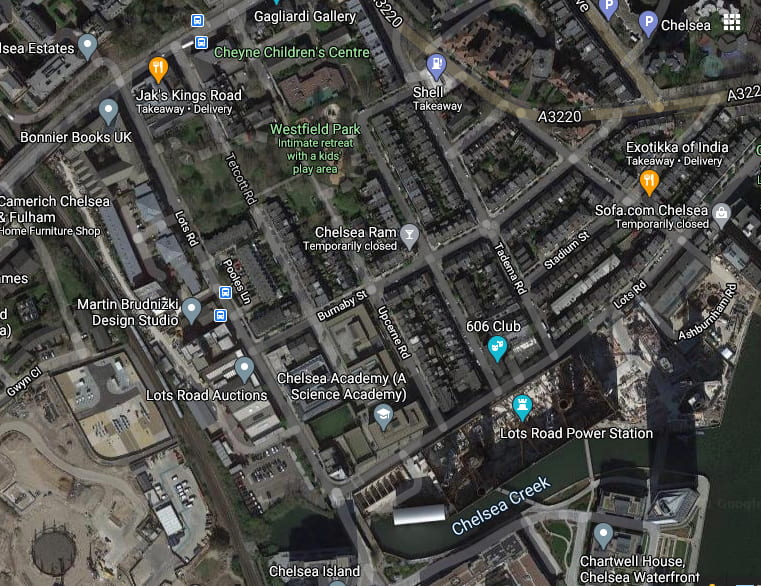

But Nigel’s centre of operations was a ‘World’s End’ away from the bijou squares and Thames embankment vistas associated with Turner, Whistler, Wilde, and Epstein.

79-89 Lots Road, Chelsea SW10 was a run-down, tatty yard on an industrial side-road backing onto what had been a recent slum clearance. When he moved in, it was still humming to the turbines of the adjacent Lots Road Power station providing electricity for the London underground.

Colin remembered that his idea of business did not chime with corporate accountants or investors: ‘Nigel understood some projects were not about making money.

“They were about staying creative, exploring new spaces, training new staff. He was always alert to the periphery, the edge where new forms arose. He documented black British poets in clubs when it was not the ‘in thing’ because he knew it was important and would be recognised as such one day.

His company became known for its access to communities and was employed by large companies to undertake market research. He also had connections to music, I think Metallica and Paul McCartney were clients of his.”

Colin enjoys recalling how Nigel found to his surprise that the vicinity of the modest workshop building, in the cheapest and least appealing part of Chelsea that more respectable and snobbish residents preferred to place in Fulham, became rather gentrified and much sought after.

- Industrial townscape of Lots Road area of Chelsea in 1920s. Image: English Heritage.

- Google satellite view of gentrified Lots Road Chelsea in 2021

A nearby creek that had been one of London’s popular fly-tipping locations had been transformed into ‘Chelsea Harbour’. International stars began driving past in their Bentleys and Rolls Royces. Even ‘south east London’s best’- Sir Michael Caine, had a condominium there, and travelled from it to Goldsmiths to pick up his honorary fellowship in New Cross in the middle 1990s:

“As the area gentrified, blue chip clients moved in. One day someone asked him about a tatty car outside the building. It was a Citroën Dyane. Nigel said it was his, the tenant said ‘but you own this building! Why haven’t you got a Merc or something?’ Nigel said why would he? It’s just a car.

Nigel was one of those lucky people who knew what was important to him. I think I would classify Nigel as a slightly eccentric, genteel Englishman; it was the source of his creativity, his imagination and his preoccupations. He had been born into a notable lineage, a descendant of Nelson, he was really rather posh but you wouldn’t know and you probably wouldn’t care. He was just a very interesting chap.”

Colin Gale says it would be right to recognise that the special pressures on ‘practice academics’ in the university did take their toll on Nigel:

“His double life of teaching and running a company started to catch up with him and he went to see many medical experts but nothing improved in the end until I believe he went and saw a Chinese herbalist and acupuncturist.

After assessing him he asked Nigel what his daily life was like and the alternative physician told him he was ill because he didn’t stop and that from now on he should stop to eat properly. After this we made a habit of always putting aside an hour that we would eat together in an era when University managers started scheduling meetings during lunch hours. We got into trouble rather frequently but we had a lot of interesting conversations.”

Colin is a major figure in art and design in British Higher Education today and anxious to give credit to his old friend and colleague:

“In the years to come his thoughts and attitudes were to become part of my own teaching repertoire. If you are lucky you meet a handful of people who shape and frame your life and Nigel was such for me.

Life is indeed made of meetings and partings but some are important. Nigel applied all his spirit and intellect to the works and ambitions of generations of students because he loved creativity. He earned his space.”

Macushla and lasting testament

Nigel’s colleagues, his students past and present, are determined that his spirit will endure at Goldsmiths.

Professor Angela Phillips said Nigel’s teaching was a testament to the belief that vocational education is an impoverishment of the soul:

“He believed that learning is not ‘a bucket to be filled but a fire to be lit’ and he lived and taught according to that ethos. He will be very much missed – even by those who argued with him most.”

Reunion of Nigel Perkins, Ian Jeffrey and class of 96-97. Image: Kind permission of Dr. Yiorgis Yerolymbos

Arnold Borgerth had worked with Nigel on the Photography MA since 1997:

“He was really inspirational, not afraid of a controversy if this is what it would take to get his voice heard, his principles and vision about what education is really about respected. Loved by our students, he will be terribly missed.

Wherever you are now Nigel, I just want you to know that we will try to do the best we can without you.”

Former student Clare Grafik recalled that Nigel Perkins believed in embracing what he described as the ‘non-functional’ in Higher Education:

“Nigel used to share some of the material and messages that would come from him and go to him around the so-called ‘non-functional’ meetings which at the time helped me in my job in the increasingly functional cultural sector!”

One such sharing was the 1935 recording by the tenor Richard Crooks of Macushla- the title of which in Irish means ‘pulse of my heart.’

Nigel had picked up the recording at an adhoc meeting of practice lecturers discussing the idea of students in different media working together and inspiring each other.

And they did. Audio and image combined. The pulse of art was beating like seeing and hearing cosmic snowballs of trailing comets in the night sky.

In the passing of a teacher like Nigel Perkins, in an Arts University such as Goldsmiths, the creative and progressive energy of his legacy lives on.

Richard Crooks singing Macushla from 78 rpm Victor Shellac disc released 1935.

Forthcoming ‘That’s So Goldsmiths’- an investigative history of Goldsmiths, University of London by Professor Tim Crook.