A composite of 13 images of Goldsmiths’ College on one postcard in November 1914

It’s the first autumn going into the winter of the Great War in 1914.

A first year 18-year-old student at Goldsmiths’ College called Wilfrid sends a composite postcard with 13 different images to a Mrs Hinchliff in South Yorkshire.

We know not whether she was a guardian, family friend, or somebody more intimate.

She may have been Wilfrid’s mentor and former teacher who helped him believe in himself and encouraged him to pursue Higher Education and a career in teaching.

The tone begins formally “Dear Mrs Hinchliff […] This card gives you some idea of the College.’

Wilfrid’s postcard ends with ‘with best wishes, and kindest regards’ (and) ‘yours very sincerely.’

What is there to read in this early twentieth century equivalent of an email or instagram sent to a married woman with the address of a small colliery worked by about 30 miners, near Sheffield, which is then diverted by the Post Office to a hotel?

What would become of Wilfrid in the ghastly carnage of the First World War that gobbled up young volunteers and conscripts like him in what became industrialised slaughter?

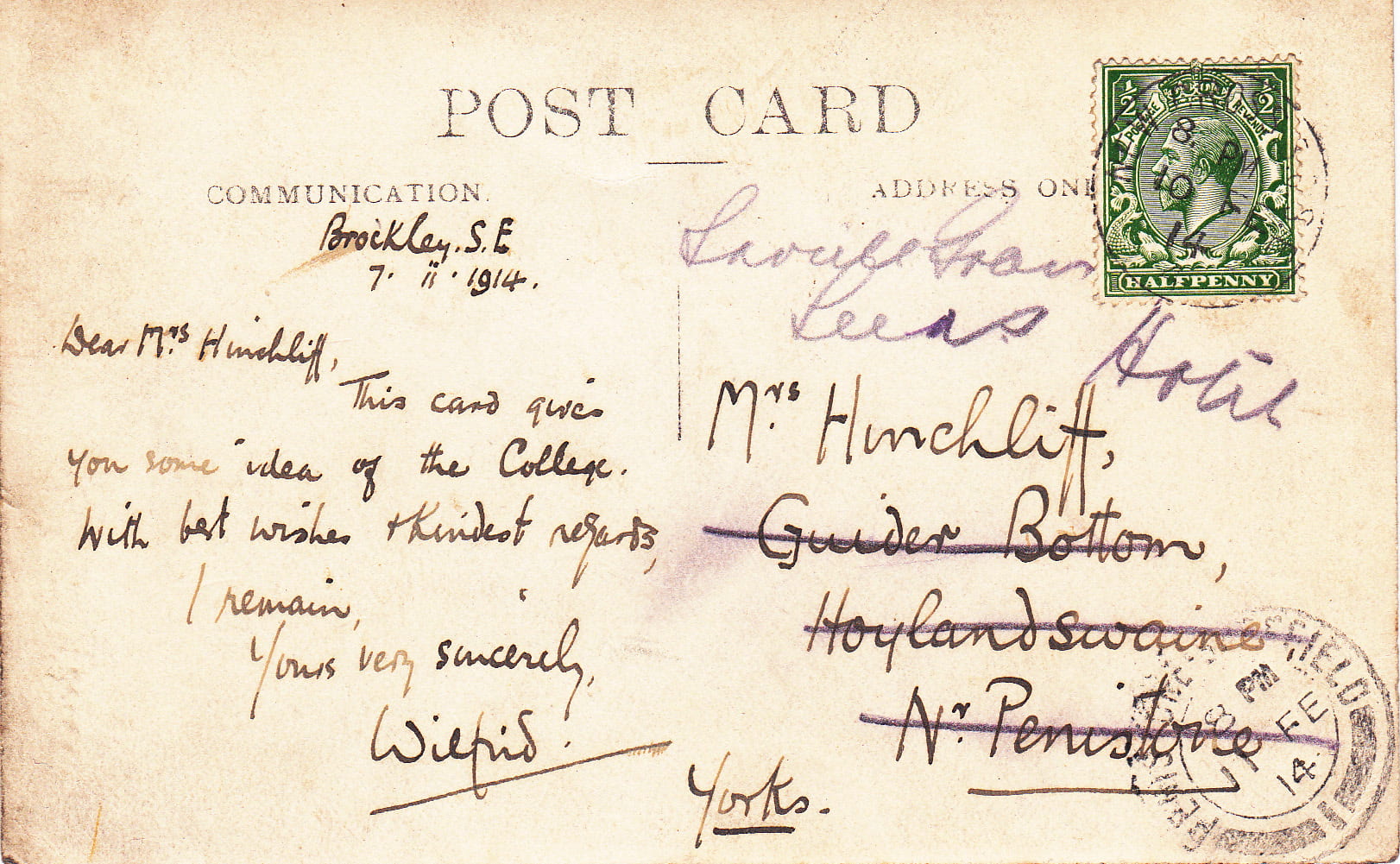

A contemporary satellite image of Hoylandswaine in Yorkshire where ‘Mrs Hinchliff’ lived. But the colliery ‘Guider Bottom’ no longer exists.

When he arrived in 1914 this group of Seniors was celebrating the completion of their two year teaching certificate courses in the Quad, which at that time was a popular meeting place for all students during lunch-time and breaks between lectures.

This photograph is so evocative because it is still possible to look out into the corner of the quadrangle and imagine them at that exact spot 105 years ago.

In shifting attention from one smiling and grinning countenance to the next the connection with past lives, personalities and all that constitutes a human being becomes so resonant.

How many of these happy young men would survive their service and experiences between 1914 to 1918?

How many would insist on becoming Conscientious Objectors and face prejudice, derision, and the punishment of military tribunals refusing to recognise and respect their pacifist beliefs?

“Jolly Good Fellows As You May See” the class of 1912-14 graduating and celebrating in the Summer of that year- only to have their teaching careers interrupted by the outbreak of global war a few weeks later. Just how many of these smiling and happy faces did not live to see the end of the First World War?

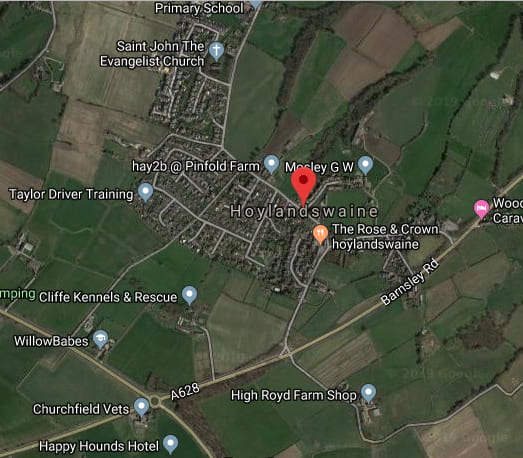

If Wilfrid was beginning his first term in 1914, the mobilising of the College’s officer training corps (OTC) would have been ever-present as is evident in this cartoon in the College’s magazine Goldsmithian.

“Smiths as Tommies”- Cartoon of increasing encroachment of army life to new students to Goldsmiths like Wilfrid in the autumn of 1914.

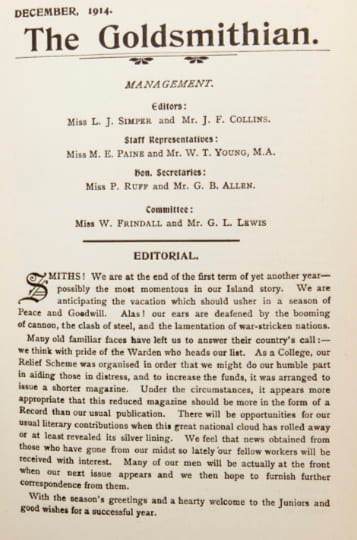

In the editorial for the college magazine published only a few weeks after Wilfrid sent his postcard to Mrs Hinchliff, he would have read this sobering editorial:

“Smiths! We are at the end of the first term of yet another year- possibly the most momentous in our Island story. We are anticipating the vacation which should usher in a season of Peace and Goodwill. Alas! our ears are deafened by the booming of cannon, the clash of steel, and the lamentation of war-stricken nations. Many old familiar faces have left us to answer their country’s call:- we think with pride of the Warden who heads our list.”

The Warden, Captain William Loring, who welcomed Wilfrid and all the other first year students that autumn, would never return to the College.

He died after being shot by a Turkish sniper at Gallipoli one year later.

Another leading member of staff named above the editorial, William Thomas Young, a popular Lecturer in English, would be killed in artillery fire on the Western Front in 1917.

The pictorial side of Wilfrid’s postcard provides an evocative composite slideshow of what Goldsmiths looked like before the First World War. The sequence of 13 photographs in columns of four, three, three and three (left to right) can also be seen as the equivalent of an instant online Youtube video.

First Column

There are four photographs.

Beginning with a view of the outside of the College main building before 1914 from where Costa Coffee is now situated.

Then the college green looking at the back of the current Richard Hoggart main building with male and female students in Edwardian dress. The viewpoint position is from the current path just before it gets to the tennis courts.

The tennis courts pre 1914 were situated in the quadrangle currently between the main refectory and lecture-rooms off Kingsway corridor.

The fourth image is the Great Hall with the magnificent organ in its original Art Nouveau design and the dais dressed in flowers for some ceremonial occasion and the floor crammed with chairs.

The viewpoint is from the doors entering from what is now reception.

Second Column

The college library in those days was situated on the second and third floor of the main building, mainly to the north eastern side parallel to what is now Dixon Road.

The photograph depicts a woman student seated poring over books and a man standing somewhat furtively behind watching her.

Is he a librarian about to tell her of a book he’s found for her, or an admirer who wants to invite her to tea?

What is described as the Dining Room, wonderfully laid out with white table cloths on the trestle tables, carafes of water, vases of flowers and cutlery is the current Cafe 35 and the viewpoint is from where Chartwells staff would see you ordering your cappuccino and croissant.

The far wall seen there would now extend beyond the walls of one or two rooms partitioned in the current structure, and what you see as a huge carved coat of arms has been replaced in 2019 with Josh Drewe’s mural on the history of Goldsmiths and its surrounding community.

The outline of the carving looks like Goldsmiths’ College coat of arms with the Latin motto Justitia Virtutum Regina– ‘Justice Is Queen of Virtues’ seen below.

Recollecting the Goldsmiths’ motto of all those years ago seems so relevant in 2019 when the University has inaugurated its first law degree.

Goldsmiths’ College coat of arms with the motto ‘Justitia Virtutum Regina- Justice Is Queen Of Virtues.

The third bottom image in this column is a picture of ‘an art room’ and looks like one of the current ground floor lecture-rooms at the back of the current main building perhaps with windows looking out onto the back field (now called the Green).

Third Column

At the top we begin with ‘The Nature Study Room’- now likely to be another current lecture-room probably on the ground floor with tall windows looking out onto the back field.

No signs of wild-life in the picture, or fauna and flora exhibits. Perhaps nature was more of a theoretical consideration.

The following images in this column are quaintly described as the Women’s Common Room and the Men’s Common Room.

It is possible to detect how they have been gender-valued in interior design and furniture.

In the men’s room there is a huge snooker/billiard table, and there are pictures on the wall seemingly of sports teams etc. The chairs are solid and hard-backed.

There are rugs on the floor perhaps ready to accommodate an impromptu wrestling match to settle old scores.

In contrast the women’s room is full of soft furnishing, table covers, cut flowers in vases, and the pictures on the walls seemingly portraits of high women achievers in staff and student faculty from the past.

Some of the chairs are soft cane-backed.

Fourth Column

We start with the gymnasium then situated where the current main College refectory is.

It’s full of large gymnastic and exercise contraptions built to stretch the human frame to breaking point and there’s a burly ‘tough guy’ with moustache apparently dressed in fencing regalia.

Next something labelled as ‘The Museum’- full of models and objets-d’art.

As a historian one wonders what treasures lay on the tables and shelves here and regret the fact that Goldsmiths no longer has any museum.

Though it could be argued that Special Collections in the Library is certainly its equivalent with its regularly held exhibitions from the archives and unique holdings such as the Women’s Art Library, Goldsmiths Textile Collection and Constance Howard Gallery, and the Daphne Oram Archive.

The last image in Column Four is of the College’s beautiful Art Nouveau swimming pool largely constructed out of wood and fine carpentry.

It was created for the Recreative and Technical Institute from 1891 and sadly was burned down during World War Two and never reconstructed.

Its location was behind the George Wood theatre and Drama and Performance suite of buildings.

It was situated at right angles to the main building and would have been accessed via the main corridor.

What’s so lovely about the photograph is the sun streaming through the huge naval style port-hole window, and the spectators leaning over the balconies.

The changing cubicles can be seen running on either side of the pool.

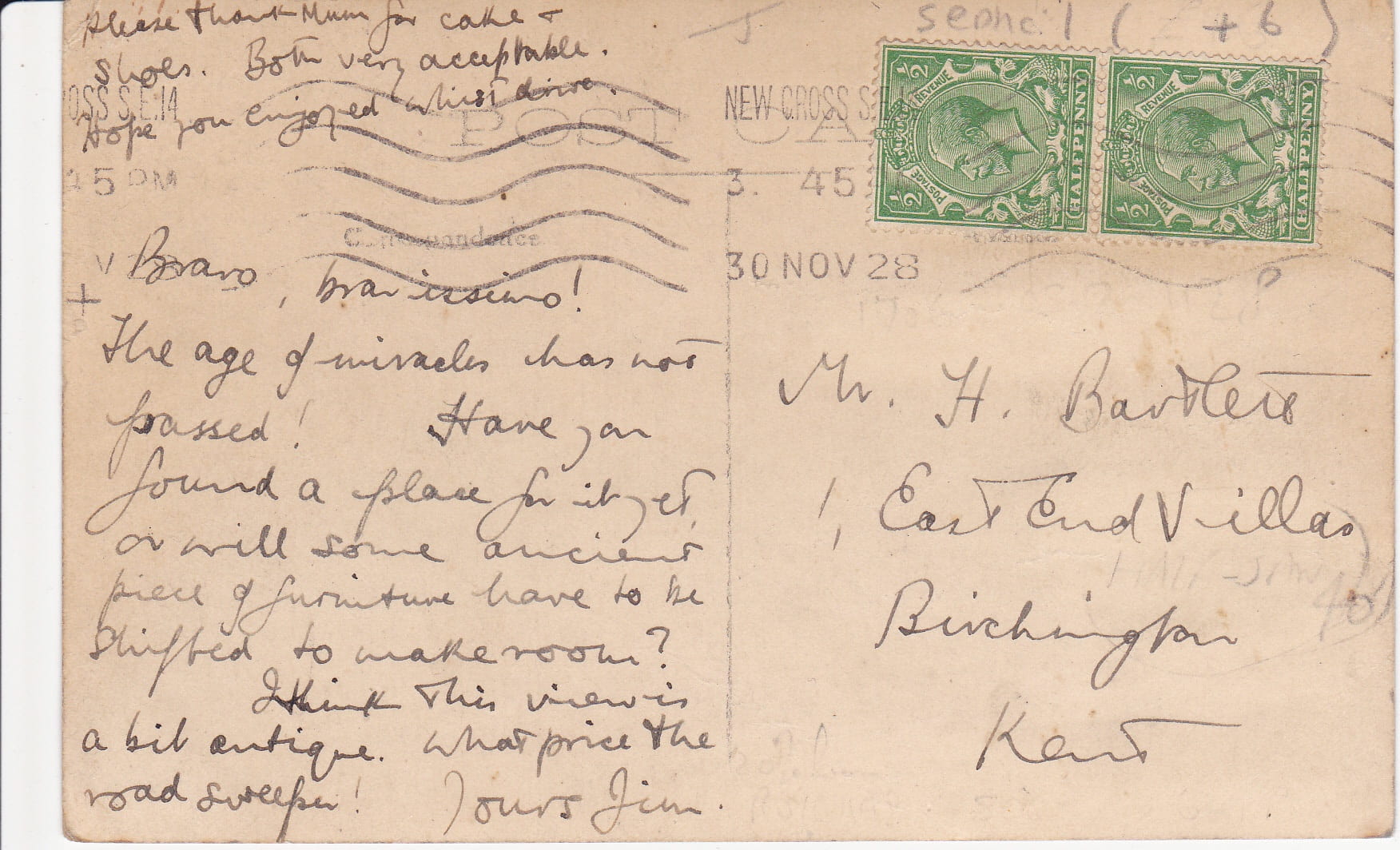

Jim Bartlett’s postcard sent to his father in 1928 is a picture of the College most probably from 1905.

In November 1928, trainee teacher Jim Bartlett is just settling in to his studies and life at Goldsmiths’ College.

He’s full of joie-de-vivre and writes to his father Henry, a successful builder with an impressive family home at 1 East End Villas, Birchington, in Kent:

“Bravo bravissimo! The age of miracles has not passed! Have you found a place for it yet? Or will some ancient piece of furniture have to be shifted to make room? I think this view is a bit antique. What price the road sweeper! Yours Jim.”

Jim has clearly found and sent something to his Dad- a birthday present perhaps. It sounds like a modern piece of furniture. What a charming term of affection for his father ‘bravissimo!’ which in Italian is the highest form of praise.

It is what one might say to a singer who has just completed a fantastic performance in an opera.

The picture of Goldsmiths’ College certainly belongs to how it looked more than 20 years previously- most likely 1905 or 1906.

The small children are in early Edwardian clothes- young children were dressed in the fashion of adults at that time.

There was no such thing as children’s fashion.

And the ‘road sweeper’ identified by Jim is the legendary Goldsmiths’ College ‘beggar’ nick-named ‘Cripps’ by students in 1910 because his moustache reminded them of the notorious wife-killer Dr. Hawley Harvey Crippen put on trial for murder at the Central Criminal Court, found guilty and executed.

‘Cripps’ had a road sweeping pitch there for decades stretching way back to the Victorian times of the Goldsmiths’ Company’s Recreative and Technical Institute, and the Royal Naval School before that.

It may be a short postcard, but the writing is full of ebullient character, zest and charm: ‘Please thank Mum for cake and shoes. Both very acceptable. Hope you enjoyed Whist drive.’

What more can a new student arriving at Goldsmiths ever want, even in 2019, but cake and shoes from his mum!

In 1928, all women would be given the equal franchise in the General Election to follow.

With private motoring booming, deaths on the road through traffic accidents are soaring.

Well over 5,000 people have been killed in just one year. The Austin Seven is the car most people can afford at £225.

The Oxford Morris Minor car has been launched in August 1928.

The Highway Code would not be published until 1931, and driving tests not introduced until 1935.

Everton’s centre forward Dixie Dean has scored a record 60 goals in the football season ending, and artists Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth stage their first London exhibitions.

It would be the year that Professor Alexander Fleming at St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington would discover the potential antibiotic properties of the blue mould penicillium notatum.

This is what Goldsmiths’ College looked like from the air in 1928. There are no buildings around the back field, nor indeed the upper field which is the site of the present Professor Stuart Hall and Lockwood buildings. The wonderful Art Nouveau swimming pool can be seen behind the George Wood Theatre, which in the 1920s still had the original Chapel tower and parallel with the bend in Dixon Road.

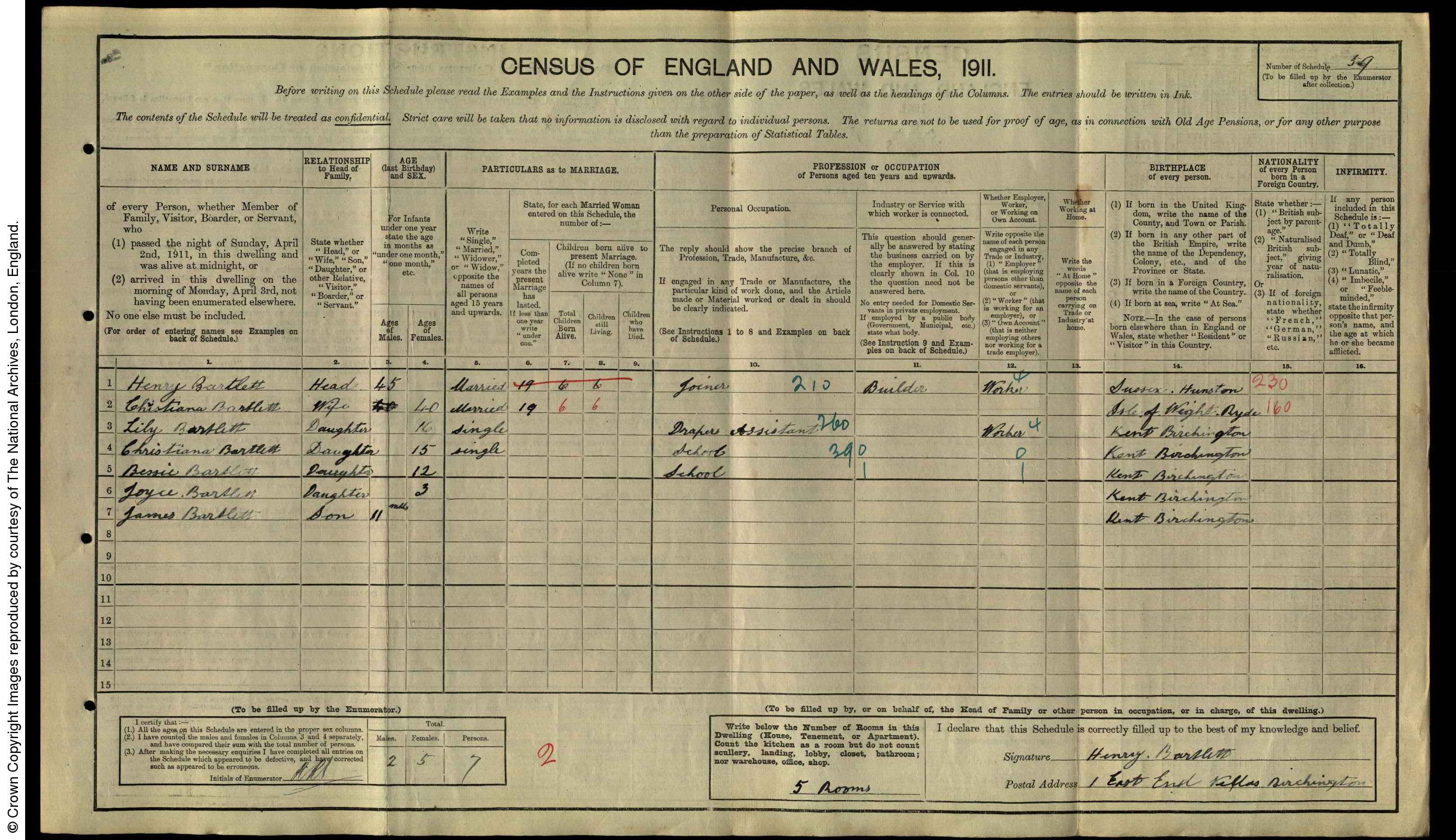

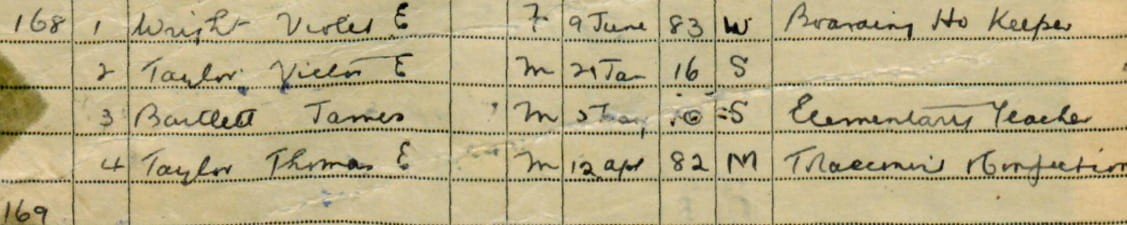

Goldsmiths trainee teacher Jim Bartlett was born in 1910. The 1911 census reveals that he had four older sisters.

In 1928 his father was 63 years old, most likely retired- hence his enjoyment of card games such as Whist Drive, and his mother Christiana 58 years old.

Whist is not as popular as it was in the 1920s.

An alternative to Bridge, three of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes detective stories feature the card game.

In The Adventure of the Empty House, Ronald Adair plays whist at one of his clubs shortly before he is murdered.

In The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot, Brenda Tregennis plays whist with her brothers George, Mortimer, and Owen shortly before she is murdered.

In The Red-Headed League, the banker Mr. Merryweather complains that he is missing his regular rubber of whist in order to help Holmes catch a bank robber.

There is no evidence Henry had any involvement in any Sherlock Holmes style mystery murder, or that he was a round the world traveller such as Jules Verne’s Phileas Fogg, a frequent winner at Whist when not quietly reading newspapers.

1911 census showing the Bartlett family living in Birchington. Jim is the youngest at 11 months old.

By the time of the Second World War, Jim was working as an elementary school teacher living in lodgings in Margate.

The 1939 national register taken in September after the outbreak of the Second World War. Jim Bartlett is well into his teaching career with a post at an Elementary School in Margate where he is living in lodgings in the seaside town.

Jim would die in Brighton in 1986. It would appear he was single and had no children.

The house in the Kent village of Birchington, where he was brought up with sisters Joyce (3 years older), Bessie (12 years older), Lily (14 years older), and Christiana (same forename as his mother and 15 years older), no longer exists.

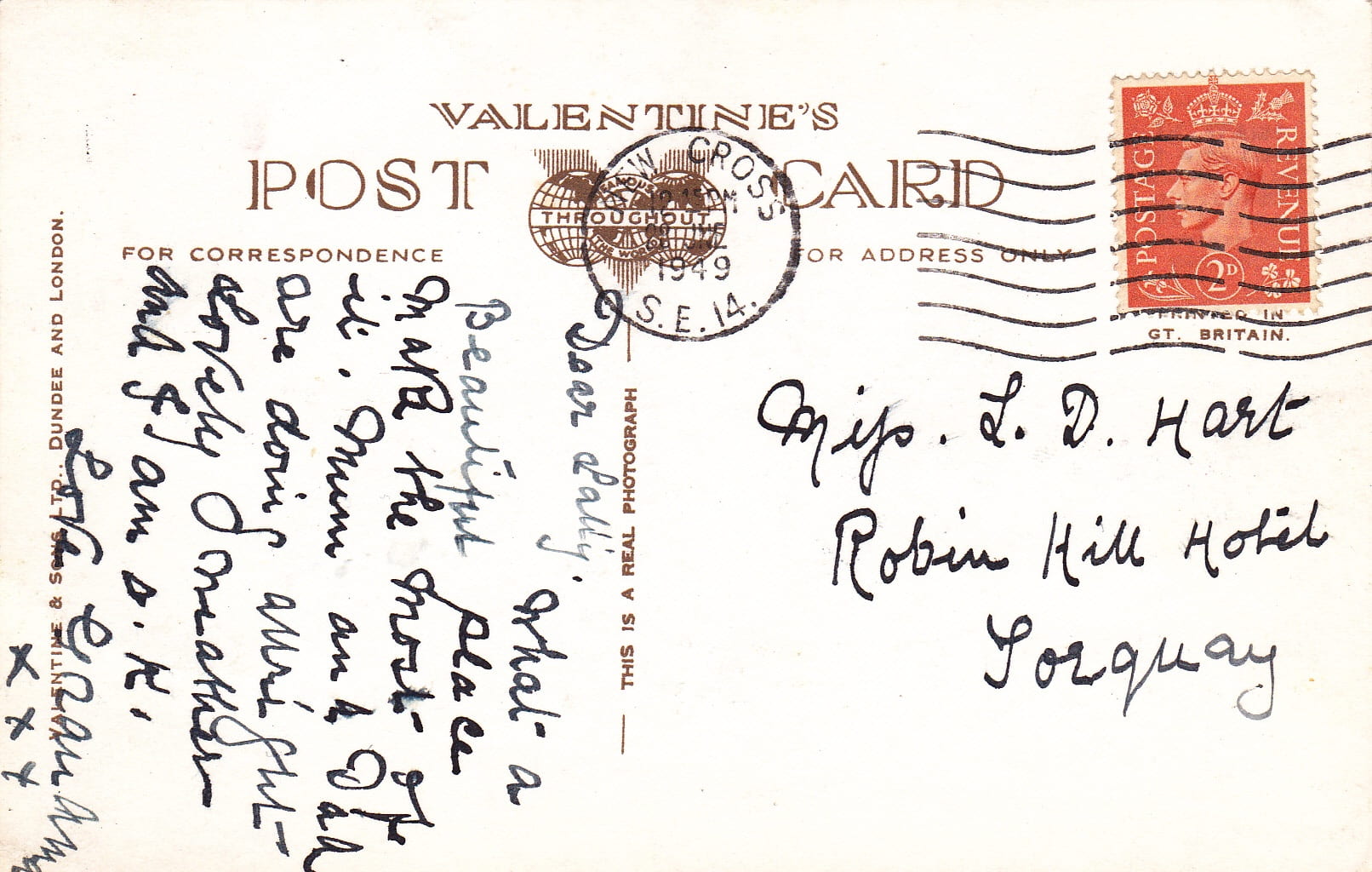

This postcard sent to Miss Sally D. Hart by her grandmother in 1949 is clearly a picture of Goldsmiths’ College in the 1930s.

It’s June 1949 and a grandmother with shaky handwriting, presumably because of her age, writes to 18 year old Sally D. Hart who we can also assume has just been awarded a place at Goldsmiths’ College.

Grandma has been checking out the place.

The postcard is definitely a picture of the front of the College between the wars and doesn’t show how the Luftwaffe and flying bombs smashed and battered the Victorian buildings that have been repaired using emergency funds and building materials.

By now the swimming pool is no more. The tall chimney stacks have gone. The front gate columns are scarred with shrapnel, but the trams are still running down Lewisham Way.

“Dear Sally, What a beautiful place. Make the most of it. Mum and Dad are doing alright. Lovely weather and I am O.K. Love Grandma X X X”

The chain-smoking King George VI is still on the throne.

Some war-time rationing is still in place though in 1949 it was ending for chocolate, sweets and clothing, and unlike her predecessors, Jim in 1928 and Wilfrid in 1914, Sally won’t have to worry about having to pay medical bills.

The National Health Service has been operational for a year.

The education system divides state educated children by the eleven-plus examination giving a minority the privilege of going to grammar school and getting middle-class professional jobs, and the rest going to secondary modern and technical schools where their futures would be mainly in trade, factories and industry.

The first launderette has opened in Bayswater.

Sally is presumably having a holiday at the Robin Hill Hotel in Torquay, which still exists to this day.

The Robin Hill Hotel in Torquay in 2019- just as it most probably looked in 1949 where Sally D. Hart was either staying on vacation or working at a summer job.

It’s also possible that her family owned it, or it was where she was working at a summer job before beginning her studies at Goldsmiths in September.

Sally would be joining Britain’s largest teacher training college with an art school that would shortly be nurturing the talents of the great art faker Tom Keating, and the brilliant designer Mary Quant.

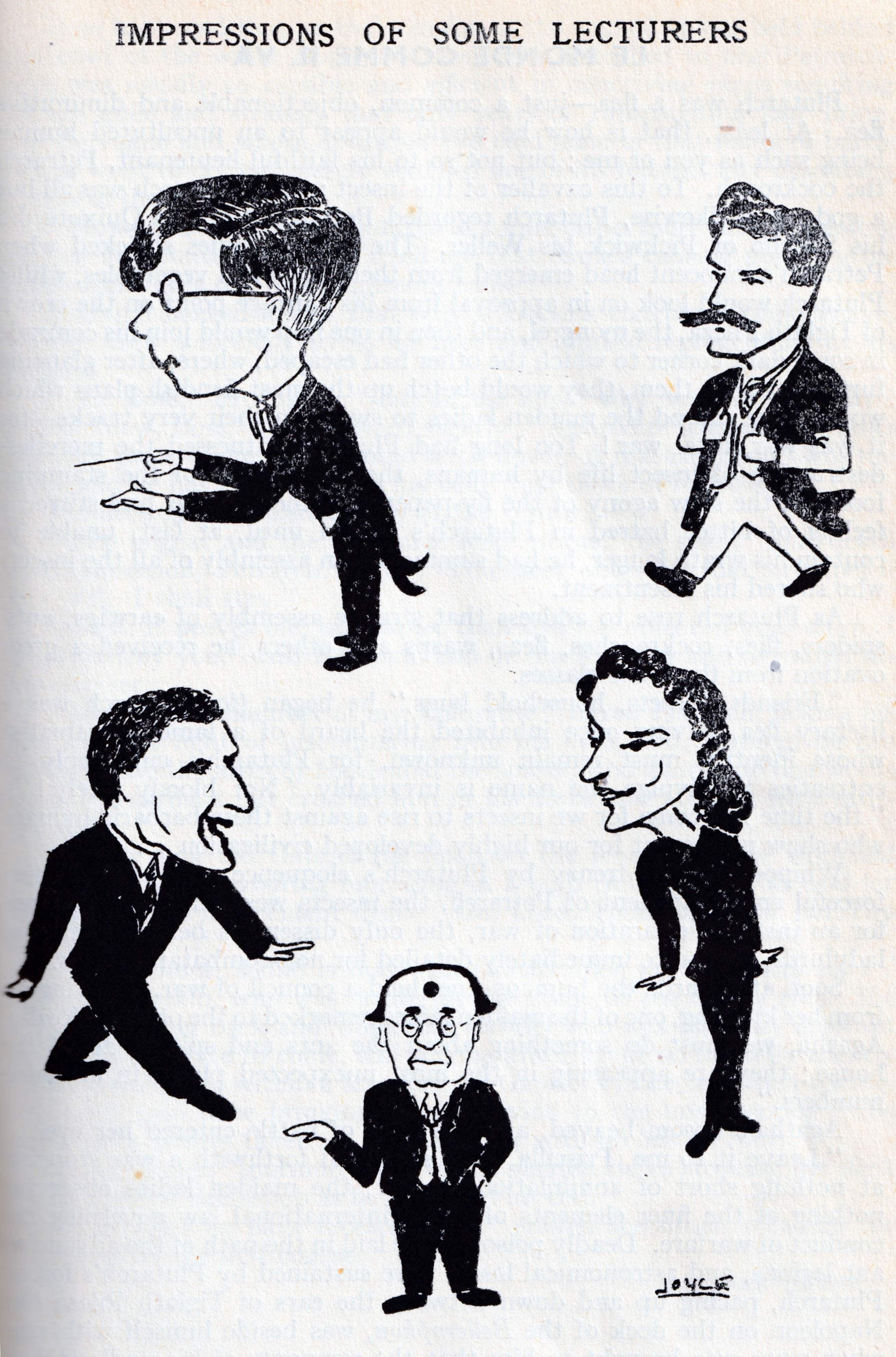

In 1949 the Art students had been busy caricaturing their lecturers.

An art student called ‘Joyce’ caricatured College lecturers for the Magazine ‘Smiths in 1949.

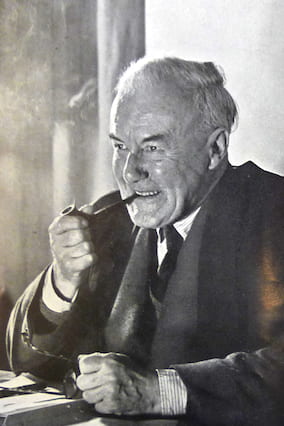

The Warden, Arthur Edis Dean has been running the College since 1927.

He led the war-time evacuation to Nottingham between 1939 and 1946 and it is has only been three years since Goldsmiths has literally risen from the ashes and revived teaching and learning in New Cross.

When Warden Dean was Sally’s age he had already graduated from Durham University. He was an intellectual child prodigy.

Arthur Edis Dean, Warden of Goldsmiths’ College 1927 to 1950.

And so we have three postcard snapshots of the lives of three students from the past and the charming connections with their family and friends.

Sally Hart’s grandmother in 1949 having a look round the College, and clearly bursting with pride over the fact that her granddaughter has won a place to study there.

Jim Bartlett sending thanks for the cake and shoes from his mother in 1928, and hoping his ‘Bravissimo’ Dad, Henry, has had an enjoyable Whist Drive.

And an apprehensive and very polite Wilfrid in November 1914 sending Mrs Hinchliff a composite postcard giving thirteen pictures of Goldsmiths College just as the Great War is brewing up into a furnace of destruction, grief and despair.

Nowadays these messages, in all likelihood, would be by Instagram, Twitter, email, Facebook and LinkedIn.

But the sentiments, love and care by and for students at Goldsmiths, in all the twists and turmoils of an often troubling world, are more than likely to be the same.

Forthcoming ‘That’s So Goldsmiths’- an investigative history of Goldsmiths, University of London by Professor Tim Crook.