David Rogers at the entrance to Goldsmiths, University of London Richard Hoggart Main Building- named after a Warden he knew, liked and worked for. Image: Tim Crook.

It cannot be said that David Rogers has everything in common with Marcus Tullius Cicero, the Roman statesman, orator, lawyer and philosopher who lived from 106 BC to 43 BC, and was a consul of the Roman Republic.

But it certainly can be said he has something in common.

Bust of Cicero. Image: José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 4.0

He has not been a lawyer. He may not have been a statesman in the foreground. But such people equally depend on their shadow researchers, speech-writers and political advisors- in other words statesmen in the background.

David made his mark at Goldsmiths’ College between 1958 and 1960 leading the College’s debating team to win the University of London debating cup for the first time in ten years and beating la crème de la crème of the top notch University of London colleges.

It was the underdog beating the favourites. A Football League Division Two side from South London- the University of London federation’s then only satellite College South of the River, beating the Champions of the Premiership.

So Cicero has gone down as Antiquity’s Orator supreme, celebrated and heralded through the Renaissance and Enlightenment and a centre of gravity for the academic discipline of rhetoric.

And David Rogers can truly be accorded the title of Goldsmiths’ Cicero.

The debating champion

His Goldsmiths team included Roger Mackay, Malcolm Laycock and Anne Castledine, and they beat in order the mighty UCL of Bloomsbury, Westfield, Royal Holloway, and then Westminster Medical School in the final.

The debating propositions won and fought over were on nuclear disarmament and hunting. Malcolm Laycock went on to become one of this country’s cherished and respected radio broadcasters.

Press cutting from 1960 of David Rogers being presented the trophy for the University of London Inter-Collegiate Debating Tournament.

In the 1959 General Election David was Chair of the College’s Conservative Association and he shared a flat with his debating team-mate Roger Mackay, who happened to be Chair of the College’s Labour Society.

David asks: ‘Would that happen today with the fashion for vitriol and not wanting to find and share what we have most in common rather than what divides us?’

Roger would be elected a Labour Councillor for the old Deptford Borough Council serving on the committee responsible for bathhouses and swimming pools.

David remembered that the Goldsmiths victory in the debating cup made big waves in the university world:

“At the time I had no idea of the impact this victory would have. The then Warden, Ross Chesterman, later told me that the effect on staff morale was electric – Here was our College struggling to become a full part of the University and looked down upon by the major Colleges, gaining accolades in the education press for the debating achievement, which in those days was considered an essential part of the prestigious activities of universities.”

The cultural importance of debating was such that through the 1940s and 1950s, BBC Radio’s Third Programme (the precursor to BBC Radio Three) would often broadcast the final live.

The headline on Goldsmiths’ victory in 1960 was ‘Machine-gun’ Smiths lay Westminster Medics low in the talk-battle.’

Westminster Medical School had to speak to the motion that ‘Blood Sports are good, clean fun.’

The press reported:

“Opposing the motion was the Goldsmiths’ team, who ruthlessly dissected each word of the motion. Their leader, Dave Rogers, was nominated as the outstanding speaker of the evening for the perfection of his “machine-gun” technique, and their second speaker, Malcolm Laycock, also earned special praise. Together with Anne Castledine and Roger Mackay, the whole team spoke as a cohesive unit.”

In fact it was a thrashing. The motion was defeated by 163 votes to 48, and the judges declared a unanimous win for the College in New Cross, South of the River.

After completing the two year teaching certificate course, the last before it became a three year qualification, David Rogers began a distinguished career in politics.

Political researcher, advisor and writer

He helped the four minute mile pace-maker and Olympic athlete Chris Chataway gain election as MP for North Lewisham, and he became an advisor and researcher for leading Conservative politician Iain Macleod.

David’s allegiance to Conservative politics contradicts the myth that progressive ideas and activism is the preserve only of the left.

When working for another Tory MP Humphrey Berkeley, he helped draft a private members’ bill that inspired others eventually leading to the decriminalisation of homosexuality from 1967.

Berkeley’s 1965 bill sought to legalise male homosexual relations along the lines of the Wolfenden report.

His Bill was given a second reading by 164 to 107 on 11th February 1966, but fell when Parliament was dissolved soon after.

Unexpectedly, Berkeley lost his seat in the 1966 general election, and blamed his defeat on homophobia.

He believed the unpopularity and deep-seated prejudice directed against the purpose of his bill lost him thousands of voters in what should have been a safe Tory constituency.

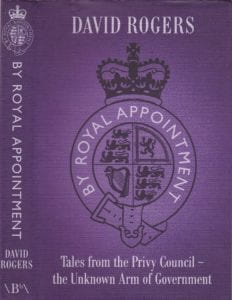

History of the Privy Council

Another reason why David Rogers merits the comparison with Cicero is that he has written two significant books on politics and constitution that are influential and important.

David Rogers’ highly regarded history and analysis of the Privy Council, published by Biteback in 2016.

His most recent By Royal Appointment: Tales from the Privy Council – the Unknown Arm of Government published by Biteback in 2016 drew plaudits from politicians, journalists and academics.

Professor of Government, Anthony King at Essex University explained:

‘Once the highway of the British state, the Privy Council is now one of its byways. David Rogers explores its exalted past and humble present with enthusiasm, charm and more than a faint whiff of nostalgia.’

David became the media’s ‘go to’ expert on the history and operation of the Privy Council; particularly when the newly elected Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, was embroiled in the controversy of whether he would have to kneel and/or kiss the hand of the Monarch on his appointment as a member of the Privy Council.

My own view is that By Royal Appointment is one of the best books I have ever read on politics and constitution. David writes with the economy and window pane precision of George Orwell and the wit of Oscar Wilde.

One of the biggest challenges of understanding and analysing British politics is grasping the nature of the writ and cultural phenomenon of the UK’s unwritten constitution.

The next is understanding and appreciating the differences between democratically elected and executively appointed politicians and the Civil Service.

Another vital contextualisation is history, class and culture.

The book will continue to be a major talking point in the history of British politics; something former Home Secretary The Right Honourable Jacqui Smith fully appreciated in her review:

“The overriding theme of this book is the way in which the privy council has evolved and adapted over the years. It is a fascinating read. However, what it has not done is to convince me that the privy council should not and could not evolve itself out of existence in the future.”

David Rogers returning to Goldsmiths for a Goldsmiths History project interview. Image: Tim Crook.

Between 1968 and 1982 David returned to Goldsmiths’ College as a Lecturer and then Senior Lecturer on the Art Teachers Certificate Course.

Goldsmiths sponsored his enrolment in 1974 for a Masters degree at Essex University in Political Behaviour for which he gained a distinction for his thesis on parliamentary secretaries. This unique intertwining of politics, art and culture most likely informs his perspective.

He can even make an appendix exquisite reading.

Such is the case with Appendix C: Order of Precedence where he explains that when looking back from the second decade of the 21st century it is:

“…amazing to realise how important the question of social status and precedence was only a short time ago. In living memory, young girls from the upper classes “came out” – a phrase meaning something quite different now.”

They were presented at court, curtsied to the Queen, and officially became debutantes, being warned by their mothers about young men who were NSIT (not safe in taxis).

He observes mischievously that ‘Presenters and interviewees on Start the Week or Question Time disdain with a shrug their membership of the House of Lords but are only too happy to embrace their titles when they go into the bars at the Palace of Westminster or use their position to vote on future legislation.’

Warden Sir Ross Chesterman 1953-1974

Sir Ross Chesterman was a more than coincidental figure in the life of David Rogers.

Sir Ross had taught at the same school in Gloucester as David’s mother. So he explains, rather self-effacingly, that after ‘messing up my A levels’ the connection was rather helpful when he applied for the two year teacher training course at Goldsmiths to start in 1958- five years after Sir Ross had been appointed Warden.

He was still Warden, when David was appointed lecturer in 1968.

He has a vivid recollection of Sir Ross Chesterman’s style and character. He remembered that on retirement ‘he was asked what was the greatest change he’d seen and replied: “When I came to the college in 1953, I had almost unlimited power. Now I am leaving, the Warden’s role has been reduced to that of limited influence!”‘

Ross Chesterman was popular with his students and they even gave him prime editorial space in the Goldsmiths Student Union Handbook for 1969-70. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London archives.

He remembered how Sir Ross provided leadership that was caring and tolerant of the huge social, political and cultural changes in education and society across the 1950s, 60s, and early 70s.

He had wit, charm and a guile that sought solutions to problems that generated the least pain, suffering, embarrassment and consternation.

The development of a youth culture market in entertainment and social recreation meant that it would be safer for students to drink and party on the campus. So he organised the first licensing of a student bar in a British University.

He regaled David Rogers with the story:

“When I come into College each day by the front entrance a monument to a previous Warden Arthur Edis Dean declares how he took the College to Nottingham in 1939, and brought it back to New Cross and shepherded its resurrection like a Phoenix from the ashes after seven years of destruction through the Blitz and the terrors of the Second World War. And then I reach the entrance and find my name on a sign above the entrance…’Ross Chesterman, licensed purveyor of wines, beers, spirits and liquors…'”

Sir Ross was a distinguished academic with a doctorate in science and certainly a respecter of the research dimension of academic culture. But as David wrote in his first very well received book Politics, Prayer and Parliament published by Continuum in 2000:

“Many years ago, when universities were somewhat different in character, the late Warden of Goldsmiths, Sir Ross Chesterman, used gently to tease the College Research Committee with Danny Kaye’s remark, “Pinch one person’s piece of work and it’s called plagiarism; pinch a hundred and it’s called research.”

The affectionate cheekiness extended to making a play on principles and principals when attending a meeting of university Vice-Chancellors and Chief Executives.

The deployment of laterally minded solutions to seemingly awkward and intractable challenges depended on a close relationship between Sir Ross and the College Superintendent, Len Lusted, who had had a distinguished Second World War record as an army officer.

In a letter from Sir Ross to David in 1998, he said of Mr Lusted: ‘He is a wonderful man and I doubt whether I could have survived at Goldsmiths without his help.’

The front of Goldsmiths’ College during the 1960s. It was an open car park and more first come first served than the present day of restrictions and permits. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London archives.

David recalled one situation in the 1960s when the College Superintendent came to the rescue of the Warden with some strategic sprinkling:

‘When the College delegacy came to hold their meetings in the Whitehead building, they would meet in a room overlooking what used to be called the Back Field (now the College Green) and in the height of summer Ross would be very worried because they would see the students indulging in what used to be described in the gentle turn of phrase ‘canoodling.’

He asked Len Lusted “What can we do about it?’ And Len said ‘Don’t worry. I’ll make sure it’s being watered from 12 o’clock to 2 o’clock. And so the concentration of the delegacy was on the business of the day instead of being diverted by the summer passions of our students.’

Journalist, Fellow and Friend of the College

In 1983, David resumed his career as an advisor in the world of politics. He provided invaluable consultative work for Goldsmiths and ‘watched its back’ during the long periods of Conservative governments.

He has been an education columnist for the Spectator and Sunday Times.

This liaison role ensured that there was always a channel of communication and understanding between the unique and complex culture of Goldsmiths, the ambitions and activism of its staff and students, and the centre of political and administrative government.

As a political advisor to Lord Whitelaw it was to the College’s advantage when such a leading Cabinet minister and politician visited New Cross to meet staff and students including those protesting loudly and disruptively against Conservative education policy.

David has always had a keen sense of the paradoxes in everyday politics when ideological mythologies simply do not square with reality:

“It was Margaret Thatcher (a Conservative Prime Minister elected into power in three General Elections) who was responsible for shutting down most of the country’s Grammar Schools and it was Harold Wilson (a Labour Prime Minister elected into power in two General Elections) who was responsible for shutting down most of the coal mines.”

David Rogers was responsible for Goldsmiths’ alumna, Mary Quant, receiving her Honorary Fellowship.

Politics, Prayer and Parliament- a new meaning for PPP? The book on religion and politics by David Rogers published by Continuum in 2000.

He was formally appointed a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Politics. Politics, Prayer and Parliament was the key research output of his Fellowship period and offers a lively and personal view by an insider both to Parliament and the Church of England about the ways religion and politics are linked and politicians and priests function through communication.

The former Prime Minister Sir John Major said it was ‘a compelling analysis of the inter-relationship of Church and State, and a shrewd guide for anyone concerned with public policy- especially if their advocacy requires speaking in public…’

David took great delight in recommending Matthew Parris’s Great Parliamentary Scandals as very high up in anyone’s reading list. Anyone harbouring ambitions for the clergy or politics should have it by their bedside so that should they ‘wake up worried in the dark watches of the night’ they could read the first paragraph:

“Many of the people in this book went to Oxford, and a large number of them were hanged. Nearly all were ordained priests or ministers, many were bishops, some were Archbishops, and one may have been the Pope. Some were formally unfrocked by Church authorities, others less ceremoniously disgraced. Most died ignominiously, or in the Rev. Harold Davidson’s case, savaged by a lion in Skegness.”

David remains an honorary Visiting Fellow of Goldsmiths and over the last three years has provided invaluable advice and assistance to the History research project.

His reserves of memory and experience have informed the research into the experience of Goldsmiths’ College students and artists who became POWs of the Japanese after the fall of Singapore in February 1942:

“When I was a lecturer on the Art Teachers Certificate course two of the longstanding art tutors Derek Cooper and Rob Brazil had been prisoners of war with the Japanese during World War Two. They would sometimes describe how they would conceal their art materials in buried tins and hide their drawings and paintings rolled up into the inside of bamboo sticks. Another former Japanese POW artist Jack Chalker was an external examiner. He had been an art student at Goldsmiths in the 1930s.”

David remains active in politics. More recently he has been working with Sir John Major to help build and catalyse the political consensus that remaining in the European Union is in the British national interest.

College bookshop during 1960s. Image: Goldsmiths, University of London archives.

David remains forever grateful for what Goldsmiths did for him as a student and lecturer:

“For the record I would really like to say that I really enjoyed my time at Goldsmiths. I got so much out of it. I made so many friends both staff and students, and in the Marquess of Granby, and I count myself extremely fortunate. Goldsmiths, I think, has a better record than most Colleges, in looking after and nurturing their former students. I know people come back and seek advice and it’s always generously given and gratefully received.”

That’s So Goldsmiths– a forthcoming history of the university is being researched and written by Professor Tim Crook.

Find out about Goldsmiths’ College student culture in the late 1960s by visiting the Golddream Exhibition in the Kingsway corridor of the Richard Hoggart Building 4th March to 14th April 2019.