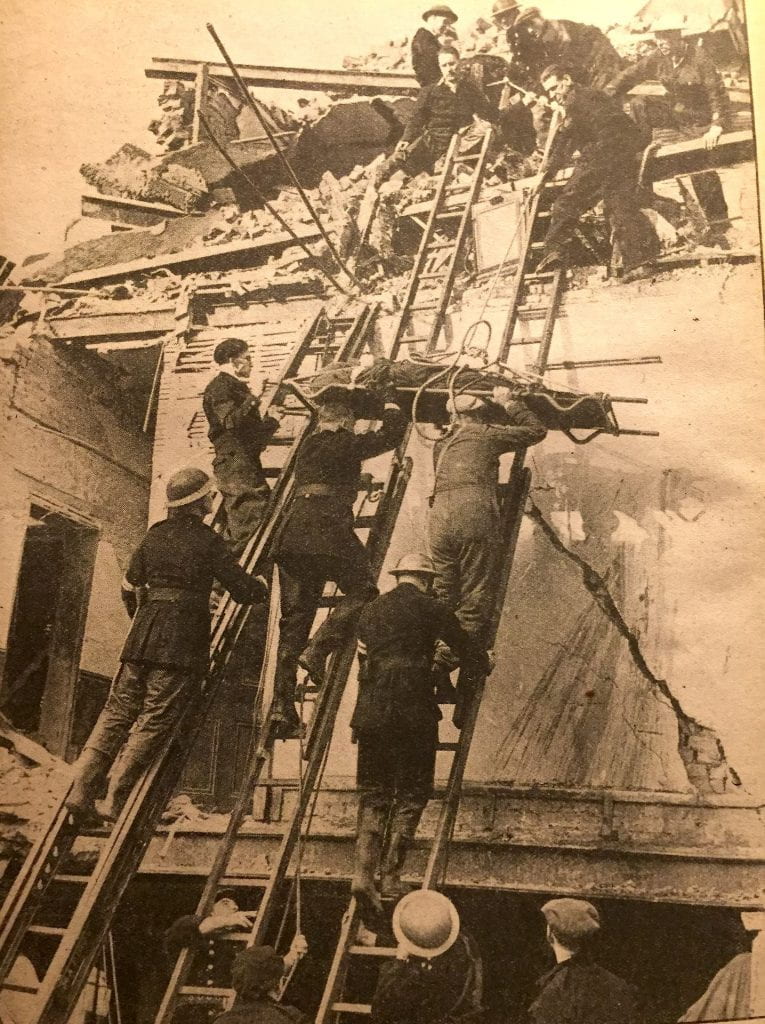

National Fire Service people and Heavy and Light Civil Defence rescue squads search for survivors of a V2 rocket bomb on London during the autumn of 1944. Image: War Illustrated.

A V2 rocket bomb which descended from the sky on the Woolworths and Coop stores in the New Cross Road Saturday lunch-time 25th November 1944 became the most devastating Home Front disaster caused by the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile.

New Cross experienced mass destruction of buildings and human life.

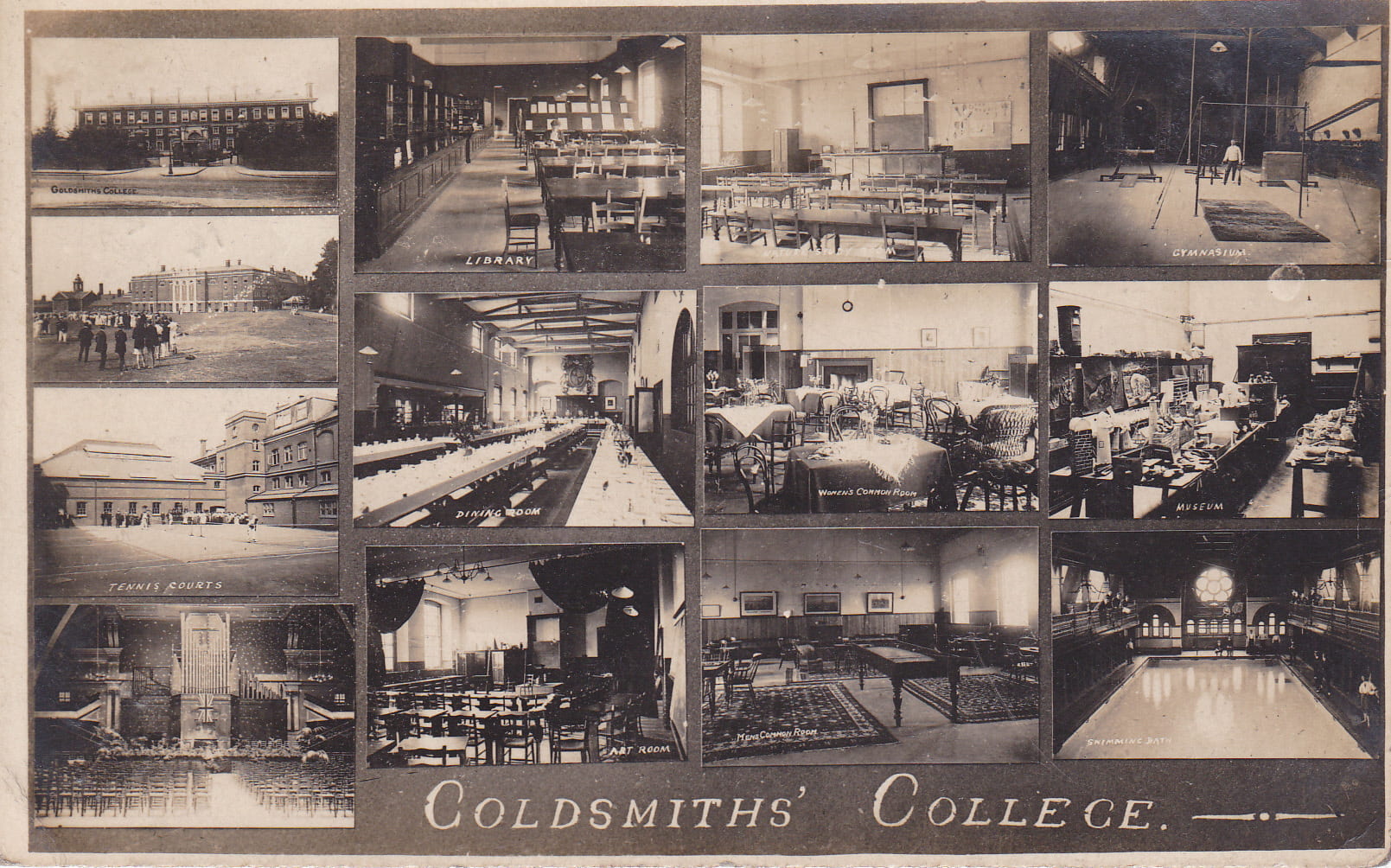

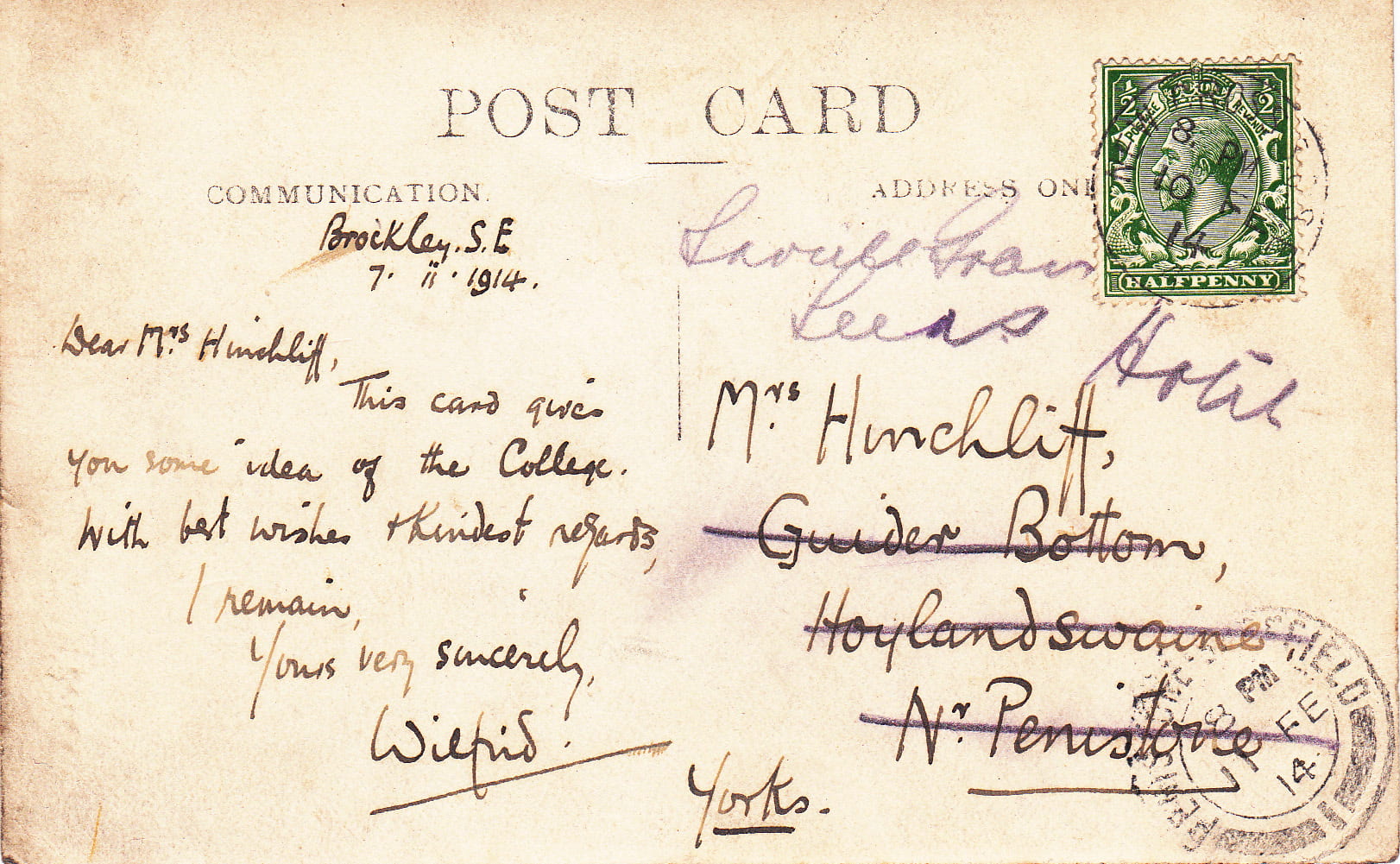

This catastrophic event happened a stone’s throw from Deptford Town Hall, now an important building used for teaching by Goldsmiths, University of London.

The people’s history dimension of this event is more bound up with the history of Goldsmiths than has hitherto been fully appreciated.

Goldsmiths now owns the site of the former St James’s Church, which has been converted into gallery and teaching spaces and is part of the memorial and human geography of what happened in the Second World War.

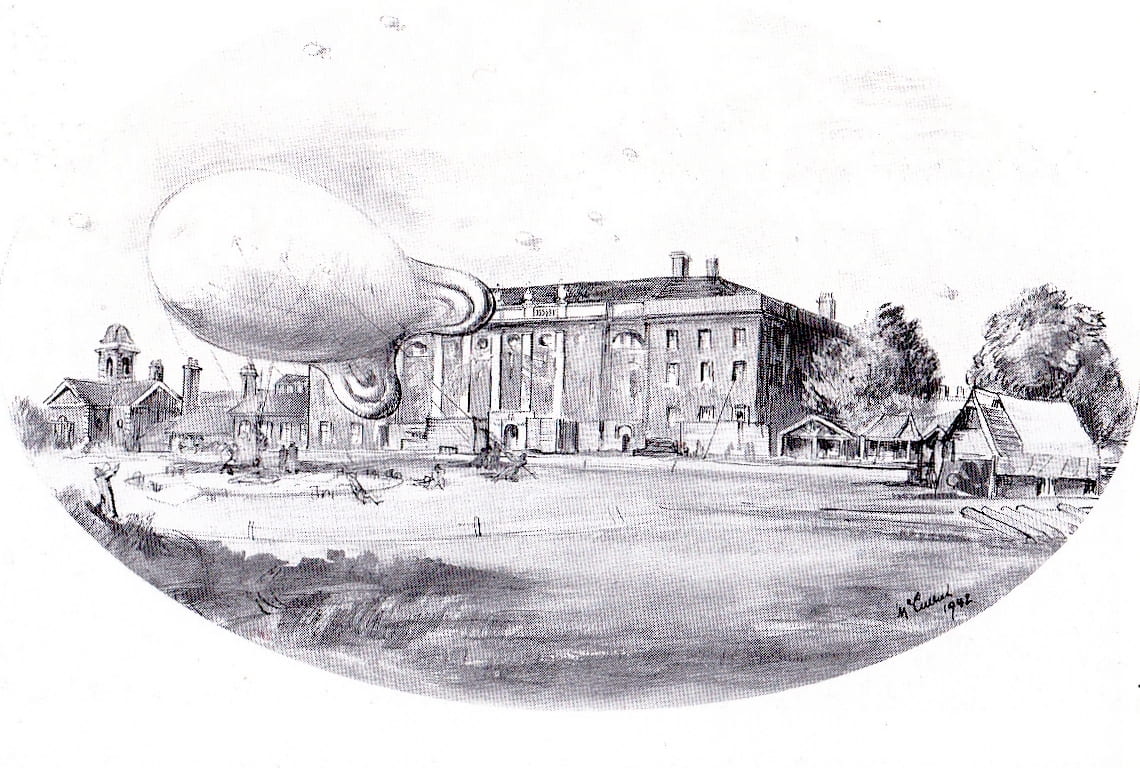

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

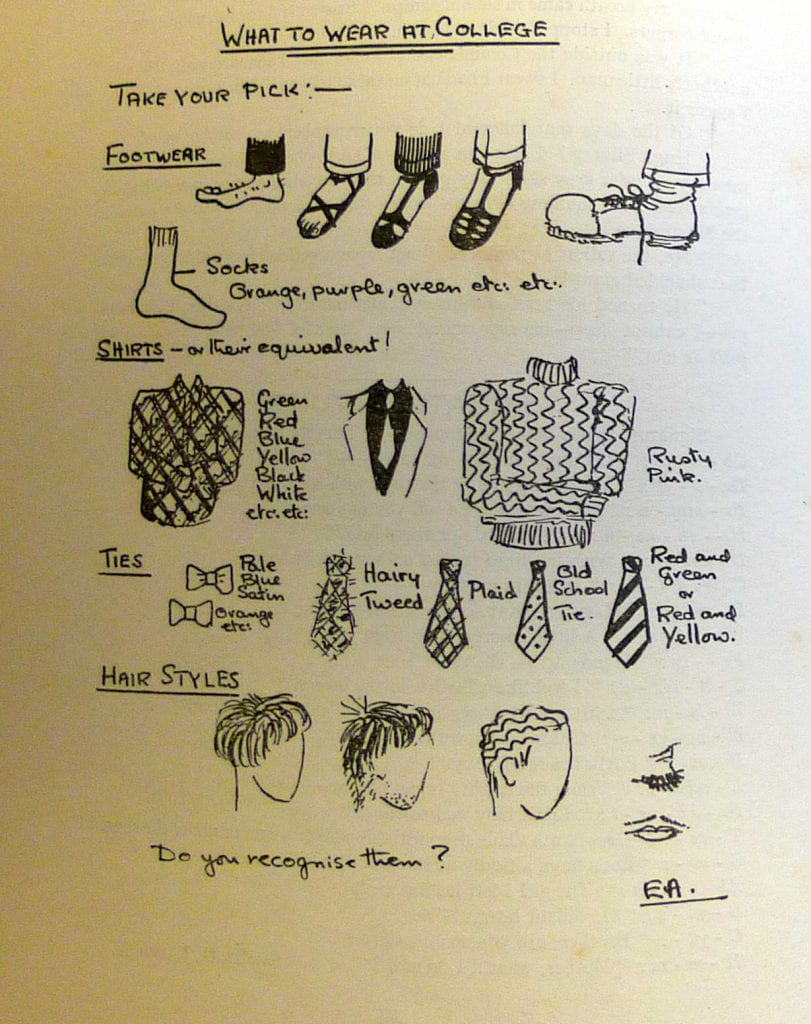

- Image: Tim Crook for Goldsmiths History Project.

Much has been written about an event which tore the heart out of the local community; largely because so many women and children died. Norman Longmate in his book Hitler’s Rockets: The Story of the V2s devotes pages 207 to 212 to a detailed description and analysis along with eye-witness accounts.

After WW2 Deptford Borough Council set about rebuilding on the site of the Woolworths tragedy and by 1947 the building now standing was constructed enabling Woolworths to return to the New Cross Road and with the provision of two storey maisonettes for council tenants above. Image: Goldsmiths History Project

But there is little evidence now of what happened either by way of commemoration to those who died or tribute to those who took part in the rescue operation. Lewisham Council Local History and Archives Centre lists the details of those who died and could be identified. It seems 23 could not.