Background to the role of Warden

It is fortunate that a historian does not have to write a job description for the role of chief executive of Goldsmiths, University of London.

To do so might discourage any application from anyone and leave this ‘unique’ of university parishes rudderless for the foreseeable future.

The fate and reminiscences of past incumbents are not particularly reassuring.

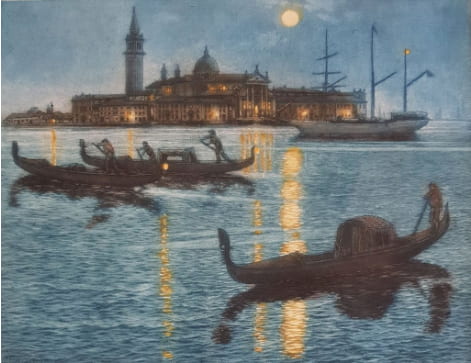

The first Warden, William Loring, was shot in the leg by a Turkish sniper in one of the Great War’s more disastrous military operations. He died on the hospital ship shortly after his leg was amputated, and his body consigned to the depths of the Aegean Sea.

Loring was the only head of a British University who went to war and never came back.

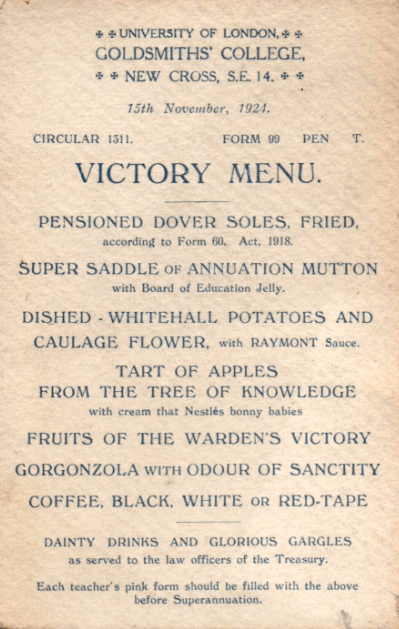

The second Warden, Thomas Raymont, said he was never happier when leaving behind the crises that year on year had threatened the College’s very existence.

On his retirement it was said that had it not been for his ‘exertions, there would have been no Goldsmiths’ College that day.’ During his last year the London County Council had plotted to take over the campus and install a new South East London Polytechnic.

Photograph from ‘The Smith’ Goldsmiths’ College magazine Winter 1954. The image of a bulldog in crash helmet and protective googles could be seen as metaphor for the resilience and challenge facing Wardens of Goldsmiths at any time during its ‘unique’ and ‘remarkable’ history.

The third Warden, Arthur Edis Dean, had to battle with Deptford Borough Council who had similar predatory designs during the Second World War.

What the council had not succeeded in achieving, the Luftwaffe nearly managed by incendiaries and high explosives.

Warden Dean, like a 20th century Merlin, conjured the rising of a Goldsmiths’ phoenix from the ashes and brought the students and staff back from their exile in Nottingham.

His successor though, Aubrey Joseph Price, found it difficult to cope with the rebellious students and staff and according to the person who took over from him, Ross Chesterman, ‘realising he was defeated, had resigned his post, taken Holy Orders and gone to run a small North of England Church College.’

Ross Chesterman was given the job in 1953 because the Cambridge graduate applicant ahead of him had exaggerated his curriculum vitae and been found out. When visiting New Cross for the first time he discovered that the ‘College situation really was quite dreadful.’

He returned home to Malvern and wished he had never heard of the place and ‘as I started sleeping badly and was frequently assailed by feelings of real terror I felt that my nerve was going completely, and I possibly faced a nervous breakdown.’

Chesterman said he was saved by Jungian therapy. He stayed to navigate a course that ran to 1974 and earned him a knighthood.

Arthur Edis Dean, though, found it difficult to leave. He kept returning in various guises- mainly participating in amateur dramatics.

According to Chesterman, he became his alter ego and something of an interfering presence always agitating against his successor’s reforms and policies.

Sadly Mr Dean was run over and killed when crossing a road in Blackheath on his way for another College sojourn in 1961.

In one case a Goldsmiths Warden decided an offer to take up a University of London post at Senate House after less than a year in New Cross was really too tempting to refuse.

The history of Goldsmiths is characterised by its association with a richness, plethora and variety of adjectives: ‘very special’, ‘inspiring’ ‘radical’, ‘edgy’, ‘quirky’, ‘eccentric’, ‘challenging’, ‘critical’ and ‘innovative.’

All of them have the potential for ambiguity and remind one of the usefulness of saying something is ‘interesting’ when you would rather not disclose emotions and feelings closer to the truth.

In the not too distant past the Goldsmiths’ Student Union made badges bearing an earthy Anglo-Saxon adverb in the middle of the refrain ‘That’s so Goldsmiths’.

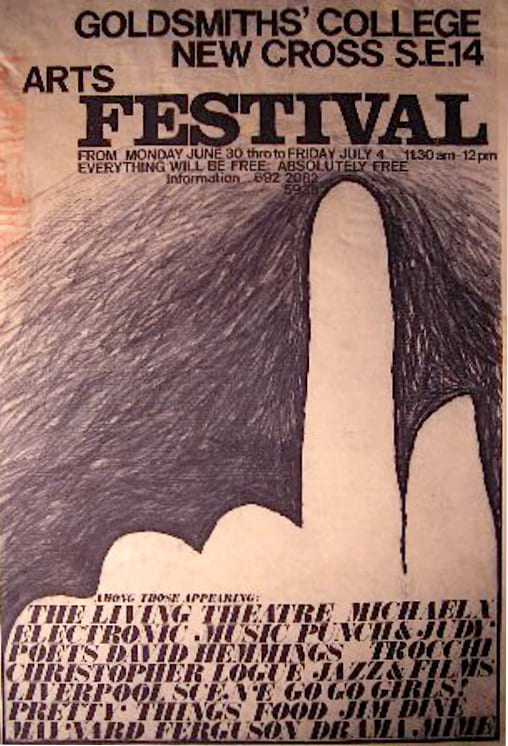

A sense of tolerating the intolerant seems to come with the territory. Student protest and revolt during the 1960s involved the future Sex Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren invading senior management meetings and squatting there with a disruptive group of fellow Art students who simply stared and remained menacingly silent throughout the proceedings.

He called this ‘Situationist political theatre.’

The patience of the mild-mannered and mellow Warden Ken Gregory was challenged by the student union in the 1990s serving up free food in protest against what was seen as inflationary refectory pricing.

McLaren’s situationist warriors protested against catering services by provoking a food fight in the Great Hall that needed a week of deep cleaning and a crane to remove the remnants of tomato and egg from the ceiling.

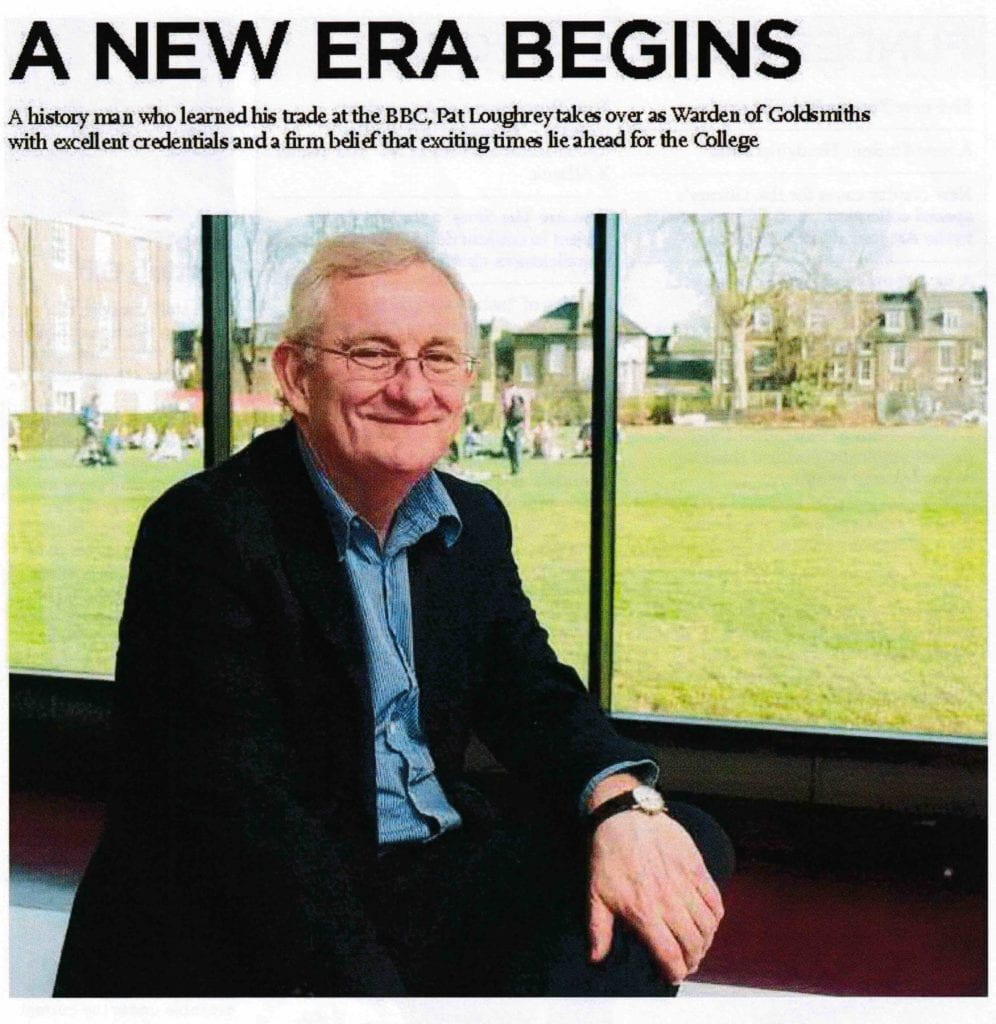

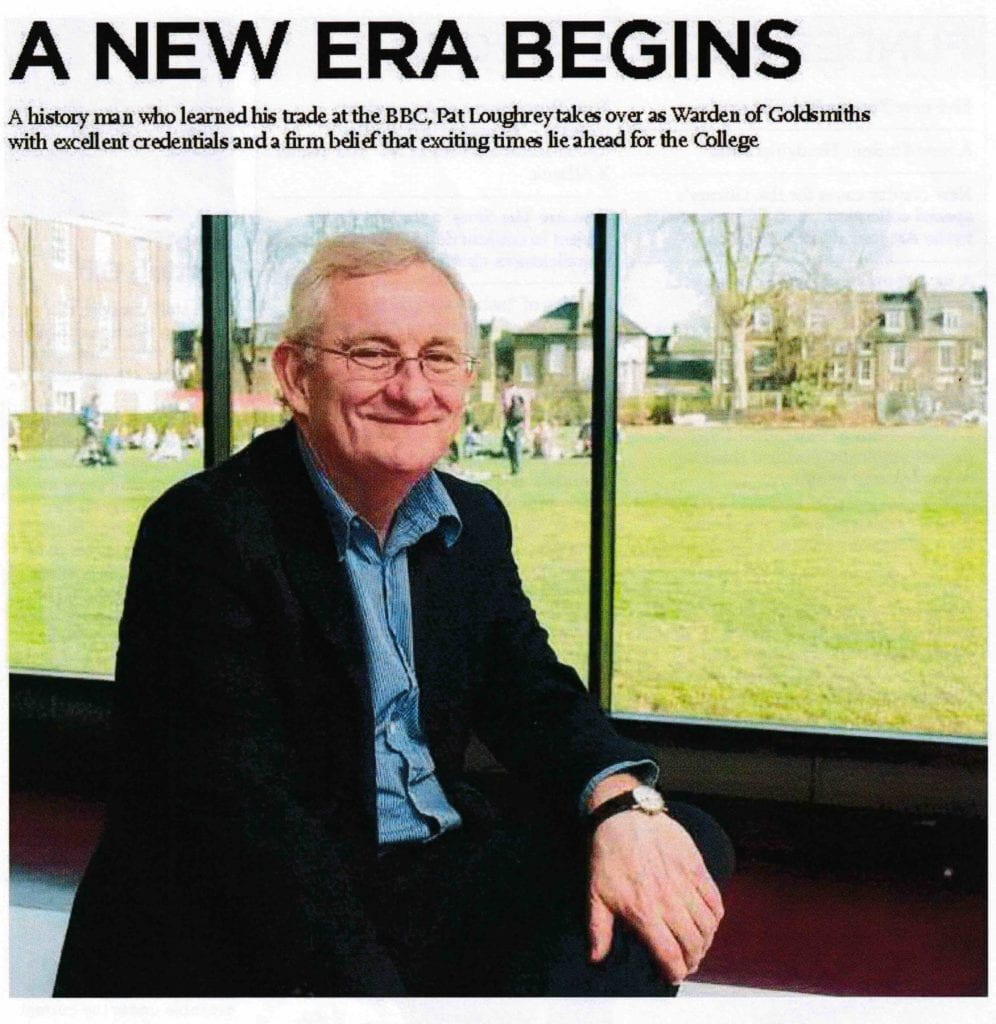

Enter Warden Pat Loughrey- a graduate of the Troubles

When Pat Loughrey arrived in 2010 he said: ‘I firmly believe that Goldsmiths has huge potential for the future.’

On his appointment in 2010, Goldsmiths called Pat Loughrey ‘a history man’ because of his degrees in the subject and a track record in history documentary at the BBC.

His first few months were certainly a baptism of fire. The Tory and Liberal Democrat coalition government tripled the cap on student fees and there were violent protests at Westminster.

The opening of the £20 million New Academic Building to accommodate Media and Communications and the Institute for Creative and Cultural Entrepreneurship on the other side of the backfield was disrupted by a loud and angry protest prompted by the fact that the guest of honour, Archie Norman, had been a minister in a Conservative Government.

Pushing and shoving, the trashing of hospitality, the noise pollution from ear-splitting sirens, whistles, and low frequency throbbing of a music machine in a pram was the welcome he received.

But the ‘That’s so Goldsmiths’ shenanigans were not going to put off or discourage the new Warden who was there for the long haul.

Read More »